1 Microsoft's Lost Decade by Kurt Eichenwald, Vanity Fair, August

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stanford-PACS-Raikes-Foundation

Stanford University Center on Philanthropy and Civil Society DRAFT - Design Thinking and Strategic Philanthropy Case Study Raikes Foundation Nadia Roumani, Paul Brest, and Olivia Vagelos August 2015 Contents Table of Contents INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................. 2 BACKGROUND OF THE RAIKES FOUNDATION ENGAGEMENT ......................................... 4 The Raikes Team’s Starting Hypotheses and Plans ...................................................................... 4 Earlier Research (June - August 2014) .............................................................................................. 6 THE HUMAN CENTERED DESIGN PROCESS (January - June 2015) ................................. 6 Identifying Beneficiaries and Stakeholders .................................................................................... 6 Ethnography, or Empathy ...................................................................................................................... 7 Interviews with donors ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Interviews with experts and stakeholders ................................................................................................... 9 Interviews with Jeff Raikes .................................................................................................................................. 9 Synthesis ..................................................................................................................................................... -

Billg the Manager

BillG the Manager “Intelli…what?”–Bill Gates The breadth of the Microsoft product line and the rapid turnover of core technologies all but precluded BillG from micro-managing the company in spite of the perceptions and lore around that topic. In less than 10 years the technology base of the business changed from the 8-bit BASIC era to the 16-bit MS-DOS era and to now the tail end of the 16-bit Windows era, on the verge of the Win32 decade. How did Bill manage this — where and how did he engage? This post introduces the topic and along with the next several posts we will explore some specific projects. At 38, having grown Microsoft as CEO from the start, Bill was leading Microsoft at a global scale that in 1993 was comparable to an industrial-era CEO. Even the legendary Thomas Watson Jr., son of the IBM founder, did not lead IBM until his 40s. Microsoft could never have scaled the way it did had BillG managed via a centralized hub-and-spoke system, with everything bottlenecked through him. In many ways, this was BillG’s product leadership gift to Microsoft—a deeply empowered organization that also had deep product conversations at the top and across the whole organization. This video from the early 1980’s is a great introduction to the breadth of Microsoft’s product offerings, even at a very early stage of the company. It also features some vintage BillG voiceover and early sales executive Vern Raburn. (Source: Microsoft videotape) Bill honed a set of undocumented principles that defined interactions with product groups. -

Partitioner Och Filsystem 2

Partitioner och filsystem 2 File systems FAT Unix-like NTFS Vad är ett filsystem? • Datorer behöver en metod för att lagra och hämta data… • Referensmodell för filsystem (Carrier) – Filsystem kategori • Layout och storleksinformation – Innehålls kategori • Kluster och block – data enheter – Metadata kategori • Tidsinformation, storlek, access kontroll • Adresser till allokerade data enheter – Filnamn kategori • Oftast ihop-kopplad med metadata – Applikations kategori • Quota • Journaler • De modernaste påminner mycket om relations databaser Windows • NTFS (New Technology File System) – 6 versioner finns, de nyaste är v3.0 (Windows 2000) och v3.1 (XP, 2003, Vista, 2008, 7), kallas även 5.0, 5.1, 5.2, 6.0 och 6.1 (efter OS version) – Stöd för unicode, säkerhet, mm. - är mycket mer komplext än FAT! – http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ntfs • FAT 12/16/32, VFAT (långa filnamn i Win95) – Används fortfarande men är inte effektivt för större lagringskapaciteter (klusterstorleken) – Långsammare access än NTFS • Windows Future Storage (WinFS) inställt projekt, enligt rykten var det en SQL-databas som ligger ovanpå ett NTFS filsystem – Läs mer på: http://www.ntfs.com/ – Och: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/WinFS FAT12, 16 och 32 • FAT12, finns på floppy diskar – Begränsad lagringskapacitet – Designat för MS-DOS 1.0 • FAT16, var designat för större diskar – Äldre OS använde detta • MS-DOS 3.0, Win95 OSR1, NT 3.5 och NT 4.0 – Max diskstorlek 2 GB • FAT32 kom när diskar större än 2GB kom – Vissa äldre och alla nya OS kan använda FAT32 • Windows 98/Me/2000/XP/2003/Vista/7 och 2008 • Begränsningar med FAT32 – Största formaterabara volymen är 32GB (större volymer kan dock användas, < 16 TiB) – Begränsade features vad gäller komprimering, kryptering, säkerhet och hastighet jämfört mot NTFS • http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FAT_file_system exFAT • exFAT (Extended File Allocation Table, a.k.a. -

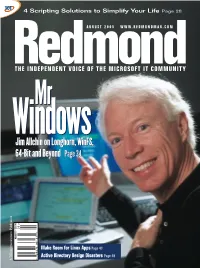

Jim Allchin on Longhorn, Winfs, 64-Bit and Beyond Page 34 Jim

0805red_cover.v5 7/19/05 2:57 PM Page 1 4 Scripting Solutions to Simplify Your Life Page 28 AUGUST 2005 WWW.REDMONDMAG.COM MrMr WindowsWindows Jim Allchin on Longhorn, WinFS, 64-Bit and Beyond Page 34 > $5.95 05 • AUGUST Make Room for Linux Apps Page 43 25274 867 27 Active Directory Design Disasters Page 49 71 Project1 6/16/05 12:36 PM Page 1 Exchange Server stores & PSTs driving you crazy? Only $399 for 50 mailboxes; $1499 for unlimited mailboxes! Archive all mail to SQL and save 80% storage space! Email archiving solution for internal and external email Download your FREE trial from www.gfi.com/rma Project1 6/16/05 12:37 PM Page 2 Get your FREE trial version of GFI MailArchiver for Exchange today! GFI MailArchiver for Exchange is an easy-to-use email archiving solution that enables you to archive all internal and external mail into a single SQL database. Now you can provide users with easy, centralized access to past email via a web-based search interface and easily fulfill regulatory requirements (such as the Sarbanes-Oxley Act). GFI MailArchiver leverages the journaling feature of Exchange Server 2000/2003, providing unparalleled scalability and reliability at a competitive cost. GFI MailArchiver for Exchange features Provide end-users with a single web-based location in which to search all their past email Increase Exchange performance and ease backup and restoration End PST hell by storing email in SQL format Significantly reduce storage requirements for email by up to 80% Comply with Sarbanes-Oxley, SEC and other regulations. -

8 Highly Effective Habits That Helped Make Bill Gates the Richest Man on Earth

8 Highly Effective Habits That Helped Make Bill Gates the Richest Man on Earth Adopting these habits may not make you a billionaire, but it will make you more effective and more successful. By Minda Zetlin, Co-author of 'The Geek Gap' How did Bill Gates get to be the richest person in the world, with a net worth around $80 billion? Being in the right place with the right product at the dawn of the personal computer era certainly had a lot to do with it. But so do some very smart approaches to work and life that all of us can follow. The personal finance site GOBankingRates recently published a list of 10 habits and experiences that make Gates so successful and helped him build his fortune. Here are my favorites. How many of them do you do? 1. He's always learning. Gates is famous for being a Harvard dropout, but the only reason he dropped out is that he and Paul Allen saw a window of opportunity to start their own software company. In fact, Gates loves learning and often sat in on classes he wasn't signed up for. That's something he had in common with Steve Jobs, who stuck around after dropping out of Reed College, sleeping on floors, so that he could take classes that interested him. 2. He reads everything. "Just about every kind of book interested him -- encyclopedias, science fiction, you name it," Gates's father said in an interview. Although his parents were thrilled that their son was such a bookworm, they had to establish a no-reading-at-the-dinner-table rule. -

'Freeware' Programs - WSJ

4/24/2021 Linux Lawsuit Could Undercut Other 'Freeware' Programs - WSJ This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. To order presentation-ready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers visit https://www.djreprints.com. https://www.wsj.com/articles/SB106081595219055800 Linux Lawsuit Could Undercut Other 'Freeware' Programs By William M. BulkeleyStaff Reporter of THE WALL STREET JOURNAL Aug. 14, 2003 1159 pm ET (See Corrections & Amplifications item below.) To many observers, tiny SCO Group Inc.'s $3 billion copyright-infringement lawsuit against International Business Machines Corp., and SCO's related demands for stiff license fees from hundreds of users of the free Linux software, seem like little more than a financial shakedown. But the early legal maneuverings in the suit suggest the impact could be far broader. For the first time, the suit promises to test the legal underpinnings that have allowed free software such as Linux to become a potent challenge to programs made by Microsoft Corp. and others. Depending on the outcome, the suit could strengthen or drastically weaken the free-software juggernaut. The reason: In filing its legal response to the suit last week, IBM relied on an obscure software license that undergirds most of the free-software industry. Called the General Public License, or GPL, it requires that the software it covers, and derivative works as well, may be copied by anyone, free of charge. IBM's argument is that SCO, in effect, "signed" this license by distributing Linux for years, and therefore can't now turn around and demand fees. -

DB/C Newsletter February 2006

DB/C Newsletter February 2006 News and Comment This month's article is a very preliminary report about Windows Vista, the next release of Microsoft Windows. I encourage any readers of this newsletter who have had experience with Windows Vista to share it with other DB/C software users via the dbctalk email list. I will be attending the EclipseCon (www.eclipsecon.org) conference in Santa Clara, California March 21-23. Be sure to make contact with me if you are also attending. I'll be reporting about the conference in next month's newsletter. [email protected] A Preliminary Overview of Windows Vista Microsoft recently announced that Windows Vista will be released in five or six different versions, depending on which press release you read. The five versions named on the Microsoft web site are Windows Vista Home Basic Windows Vista Home Premium Windows Vista Ultimate Windows Vista Business Windows Vista Enterprise One interesting thing to note is that the way versions were organized for Windows XP is going away. There will no longer be versions specifically for 64 bit processors, for the Tablet PC or for home multimedia. Windows Vista Ultimate will contain all of the home and business features of the other versions of Windows Vista. No official release dates have been announced for the different versions of Windows Vista, but it seems to be general knowledge that the home versions will be released before the end of 2006 and the business versions will follow in the first half of 2007. No pricing has been announced. -

IT Acronyms.Docx

List of computing and IT abbreviations /.—Slashdot 1GL—First-Generation Programming Language 1NF—First Normal Form 10B2—10BASE-2 10B5—10BASE-5 10B-F—10BASE-F 10B-FB—10BASE-FB 10B-FL—10BASE-FL 10B-FP—10BASE-FP 10B-T—10BASE-T 100B-FX—100BASE-FX 100B-T—100BASE-T 100B-TX—100BASE-TX 100BVG—100BASE-VG 286—Intel 80286 processor 2B1Q—2 Binary 1 Quaternary 2GL—Second-Generation Programming Language 2NF—Second Normal Form 3GL—Third-Generation Programming Language 3NF—Third Normal Form 386—Intel 80386 processor 1 486—Intel 80486 processor 4B5BLF—4 Byte 5 Byte Local Fiber 4GL—Fourth-Generation Programming Language 4NF—Fourth Normal Form 5GL—Fifth-Generation Programming Language 5NF—Fifth Normal Form 6NF—Sixth Normal Form 8B10BLF—8 Byte 10 Byte Local Fiber A AAT—Average Access Time AA—Anti-Aliasing AAA—Authentication Authorization, Accounting AABB—Axis Aligned Bounding Box AAC—Advanced Audio Coding AAL—ATM Adaptation Layer AALC—ATM Adaptation Layer Connection AARP—AppleTalk Address Resolution Protocol ABCL—Actor-Based Concurrent Language ABI—Application Binary Interface ABM—Asynchronous Balanced Mode ABR—Area Border Router ABR—Auto Baud-Rate detection ABR—Available Bitrate 2 ABR—Average Bitrate AC—Acoustic Coupler AC—Alternating Current ACD—Automatic Call Distributor ACE—Advanced Computing Environment ACF NCP—Advanced Communications Function—Network Control Program ACID—Atomicity Consistency Isolation Durability ACK—ACKnowledgement ACK—Amsterdam Compiler Kit ACL—Access Control List ACL—Active Current -

Microsoft Quiz: Questions and Answers

kupidonia.com Microsoft Quiz: questions and answers Microsoft Quiz: questions and answers - 1 / 4 kupidonia.com 1. When was Microsoft founded? 1976 1975 1977 2. Where was Microsoft founded? Old Mexico Washington New Mexico 3. Who is the founder of Microsoft? Bill Gates Mark Gates Lebron Gates 4. Where are the headquarters of Microsoft? Washington New York Mexico 5. Who has been the CEO of Microsoft since 2014? Satya Nadella Steve Jobs Microsoft Quiz: questions and answers - 2 / 4 kupidonia.com Tim Cook 6. How many stocks of the company does Bill Gates own? 7.5% 50% 70% 7. Which OS was developed by Microsoft company? Mac OS Linux Windows 8. Which company Microsoft had tried to buy in 2008 but didn't succeed? Yahoo! Google Apple 9. When did Microsoft buy Skype Limited? 1998 2011 2018 10. When did Paul Allen leave the Microsoft? 1983 1996 2002 Microsoft Quiz: questions and answers - 3 / 4 kupidonia.com Microsoft Quiz: questions and answers Right answers 1. When was Microsoft founded? 1975 2. Where was Microsoft founded? New Mexico 3. Who is the founder of Microsoft? Bill Gates 4. Where are the headquarters of Microsoft? Washington 5. Who has been the CEO of Microsoft since 2014? Satya Nadella 6. How many stocks of the company does Bill Gates own? 7.5% 7. Which OS was developed by Microsoft company? Windows 8. Which company Microsoft had tried to buy in 2008 but didn't succeed? Yahoo! 9. When did Microsoft buy Skype Limited? 2011 10. When did Paul Allen leave the Microsoft? 1983 Microsoft Quiz: questions and answers - 4 / 4 Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org). -

Using Virtual Directories Prashanth Mohan, Raghuraman, Venkateswaran S and Dr

1 Semantic File Retrieval in File Systems using Virtual Directories Prashanth Mohan, Raghuraman, Venkateswaran S and Dr. Arul Siromoney {prashmohan, raaghum2222, wenkat.s}@gmail.com and [email protected] Abstract— Hard Disk capacity is no longer a problem. How- ‘/home/user/docs/univ/project’ directory lists the ever, increasing disk capacity has brought with it a new problem, file. The ‘Database File System’ [2], encounters this prob- the problem of locating files. Retrieving a document from a lem by listing recursively all the files within each directory. myriad of files and directories is no easy task. Industry solutions are being created to address this short coming. Thereby a funneling of the files is done by moving through We propose to create an extendable UNIX based File System sub-directories. which will integrate searching as a basic function of the file The objective of our project (henceforth reffered to as system. The File System will provide Virtual Directories which SemFS) is to give the user the choice between a traditional list the results of a query. The contents of the Virtual Directory heirarchial mode of access and a query based mechanism is formed at runtime. Although, the Virtual Directory is used mainly to facilitate the searching of file, It can also be used by which will be presented using virtual directories [1], [5]. These plugins to interpret other queries. virtual directories do not exist on the disk as separate files but will be created in memory at runtime, as per the directory Index Terms— Semantic File System, Virtual Directory, Meta Data name. -

Allen Discovery Centers: Communications Toolkit

The Paul G. Allen Frontiers Group Allen Discovery Centers: Communications Toolkit 2019 The Paul G. Allen Frontiers Group Communications Toolkit for Allen Discovery Centers About this Toolkit This toolkit is designed to provide direction on how to tell The Paul G. Allen Frontiers Group story as well as guidance on how to include and integrate information about the Allen Discovery Centers (ADC) across multiple communications channels, such as your website, press releases, biography, articles and social media. Overview of The Paul G. Allen Frontiers Group For more than a decade, Paul G. Allen made awards to support extraordinary scientific minds and spark new directions in bioscience research. To date over $200M in research awards have been made, and with the 2016 launch of The Paul G. Allen Frontiers Group, a division of the Allen Institute, the award mechanisms have grown to include both Allen Distinguished Investigators as well as Allen Discovery Centers. The Frontiers Group continues to identify and foster ideas that will change the world and increase creative dialogue and pioneering approaches, through its ever-growing network of Allen awardees. We strive to have such efforts lay the foundation for a new era in biology, shaping how science can be done both here at the Allen Institute and across the globe. We are committed to a continuous conversation with the scientific community that allows us to invest in the people and approaches at the very frontiers of science and accelerate our understanding of biology. Our Mission The mission of The Paul G. Allen Frontiers Group is to uncover and make visible the emerging frontiers of science, identify pioneering explorers to create new knowledge, and produce important solutions that make the world better. -

Albers Grads Headed for Google Page 5 Albers Executive Speaker Series Page 6

A PUBLICATION OF NEWS AND CURRENT EVENTS FROM THE ALBERS SCHOOL OF BUSINESS AND ECONOMICS FALL 2010 Albers Grads Headed for Google Page 5 Albers Executive Speaker Series Page 6 Faculty Profile – Chris Weber A Passion for Helping Others Page 10 WHAT’S INSIDE? Red Winged Leadership Award Winners .................3 Albers Faculty .......................4 Research News Student Profiles: ...................5 ver the past year, the Albers School Alex Thomas and has been very honored to be Christina Davis recognized a number of times in the Obusiness school rankings of BusinessWeek and Albers Executive ..................6 Speaker Series U.S. News & World Report. This includes a Alumni Profile: .....................9 #46 ranking of our undergraduate program by Mari Anderson BusinessWeek, a #25 ranking of our Part-time Faculty Profile: ....................10 MBA program by BusinessWeek, and a #22 Chris Weber ranking of our EMBA program by U.S. News Alumni Events ....................11 & World Report. It is terrific to see the hard Message work of our faculty and staff recognized in these influential surveys. ON THE COVER: Although these recognitions are MARKETING GRADUATE ALEX gratifying, rankings are hard pressed to THOMAS TOOK SOME TIME OFF AFTER GRADUATION measure the true quality and impact of our Dean’s Dean’s BEFORE STARTING HIS JOB AT work. The faculty and staff of Albers share a GOOGLE IN CALIFORNIA. commitment to putting our students first and challenging them to be the best they can be in terms of professional excellence and service to society. We are always searching for ways to improve the quality of our programs, a result of our dedication to continuous improvement.