Esther NICHOLAS MULROY Mordecai

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MUSIK PODIUM STUTTGART 2018/19 Frieder Bernius

MUSIK PODIUM STUTTGART 2018/19 Frieder Bernius Kammerchor Stuttgart Barockorchester Stuttgart Hofkapelle Stuttgart Klassische Philharmonie Stuttgart OPEN AIR SCHLOSS SOLITUDE DIRIGENTENAKADEMIE FESTIVAL STUTTGART BAROCK 1 Sehr geehrte Damen und Herren, liebe Musikfreunde, vor Ihnen liegt unser Programm der Saison 2018/19. Es bildet das ab, was man „spezialisierte Vielfalt“ nennen kann und womit wir einen unverwechselbaren künstlerischen Beitrag für unsere Reg ion und darüber hinaus leisten wollen. Dafür brauchen wir Sie: ein Publikum, das sich für individuell interpretierte Meisterwerke eben- so interessiert wie für Unbekanntes, das als Meisterwerk erst noch entdeckt werden will. Überstrahlt wird unsere Saison vom 50-jährigen Jubiläum der Inhalt Gründung des Kammerchors Stuttgart, das wir in diesem Herbst mit zwei ganz unterschiedlichen Programmen feiern wollen: zum einen mit Aufführungen und einer Aufnahme der Missa solemnis von Beethoven, zum anderen einem A-cappella-Programm des 4 50 Jahre Kammerchor Stuttgart Kammerchors, das am 4. November in Zusammenarbeit mit der Jubiläumskonzerte „Akademie für Gesprochenes Wort/Uta Kutter Stiftung“ auch das Ende des ersten Weltkriegs 1918 vor 100 Jahren sowie die Pogrom- 8 Konzerte in Stuttgart und Region nacht 1938 künstlerisch reflektieren will. 18 Konzertkalender Immer wieder ist der Kammerchor Stuttgart zu einem Format für 12 und 16 Solostimmen zurückgekehrt, das auch in der kommenden 20 Musik Podium Stuttgart und seine Ensembles Saison sein Repertoire erweitert und besonders die klassische Mo- 22 Freundeskreis derne einschließt. Eine spezielle Gattung ist auch das Melodram, das die Hofkapelle Stuttgart in der Electra von Christian Cannabich 24 Informationen zum Konzertbesuch einer Schauspielerin gegenüberstellt. Cannabich ist ein Vertreter der sogenannten „Mannheimer Schule“. Mit seiner Electra von 1781 26 CD-Neuerscheinungen wollen wir wieder auf einen Schatz der baden-württembergischen Musikgeschichte aufmerksam machen und für den SWR festhalten. -

De Novis Libris Iudicia ∵

mnemosyne 70 (2017) 347-358 brill.com/mnem De Novis Libris Iudicia ∵ Carrara, L. L’indovino Poliido. Roma, Edizioni di Storia e Letteratura, 2014. xxiv, 497 pp. Pr. €48.00. ISBN 9788863726688. In this book Laura Carrara (C.) offers an edition with introduction and com- mentary (including two appendices, an extensive bibliography and indexes) of three fragmentary plays by Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides, which focus on the story of a mythical descendant of Melampus, the prophet and sorcerer Polyidus of Corinth, and his dealings with the son of Minos, Glaucus, whose life he saved. These plays are the Cressae, Manteis and Polyidus respectively. In the introduction C. gives an extensive survey of the sources on Polyidus in earlier periods and in literary genres other than tragedy. He plays a sec- ondary part in several stories (as in Pi. O. 13.74-84, where he is helping Bellerophon to control Pegasus) and only in the Cretan story about Glaucus he is the main character. C. observes that in archaic literature we find no traces of this story, but even so regards it as likely that the tragic poets did not invent it (perhaps finding it in an archaic Melampodia). Starting from Il. 13.636-672, where Polyidus predicts the death of his son Euchenor, C. first discusses the various archaic sources in detail and then goes on to various later kinds of prose and poetry, offering a full diachronic picture of the evidence on Polyidus. In the next chapter C. discusses a 5th century kylix, which is the only evidence in visual art of the Cretan story and more or less contemporary with the tragic plays. -

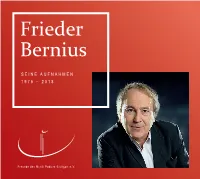

Frieder Bernius

Frieder Bernius SEINE AUFNAHMEN 1975 – 2018 Freunde des Musik Podium Stuttgart e.V. Vorwort Meine Tonaufzeichnungen – auf der Suche nach dem goldenen ist im Gegensatz zur Literatur und Malerei zu können. Denn für mich ist der Unterschied Schnitt zwischen Ausdruckscharakter und technischer Perfektion „flüchtig“, deshalb kann man ihre Ergebnisse zwischen Livekonzert und Studioaufnahme nicht erneut abrufen, überprüfen und festhalten. vergleichbar mit einem gefilmten Livekonzert und einer Filmproduktion. Da geht es nicht Jeder Interpret eines musikalischen Werks ist in dieser Situation der Überprüfung, dass seine Im Lauf der Zeit, vor allem mit dem Beginn nur um die größere Vollkommenheit des Er- damit befasst, gleichzeitig seinen Klang zu emotionale Empfindungswelt eine ganz andere der digitalen Aufzeichnung, hat die sogenannte reichbaren durch die Möglichkeit, in einzelnen entwickeln und diesen in die Architektur des ist als zum Zeitpunkt der Klangentstehung. „Postproduktion“, also die technische Nach- Abschnitten zu denken, sondern vor allem Werkes einzubringen. Er ist also mit dem Augen- Denn um Klänge unmittelbar und vor der bearbeitung von Aufnahmen, erheblich an darum, die verschiedenen Anläufe nachträg- blick der Klangerzeugung ebenso beschäftigt Öffentlichkeit zu erzeugen, erfordert es andere Gewicht gewonnen. Was wären a cappella- lich unter die Lupe zu nehmen und den goldenen wie er die Form des Werkes vom ersten Ton Voraussetzungen und eine andere Einstel- Aufnahmen ohne die Möglichkeit des „pitch- Schnitt zwischen Ausdruckscharakter und tech- an voraussehen muss. Zu einem kontrollieren- lung zu ihnen, als wenn sie mit der nötigen shifts“ (Tonhöhenveränderung), was wäre ein nischer Vollkommenheit aus der gewonnenen den Nachhören der gestalteten Klänge kann Distanz abgehört werden – zumal mit der optimales Gleichgewicht von Chor und Orches- Distanz zu finden. -

Handel's Sacred Music

The Cambridge Companion to HANDEL Edited byD oNAtD BURROWS Professor of Music, The Open University, Milton Keynes CATvTNnIDGE UNTVERSITY PRESS 165 Ha; strings, a 1708 fbr 1l Handel's sacred music extended written to Graydon Beeks quake on sary of th; The m< Jesus rath Handel was involved in the composition of sacred music throughout his strings. Tl career, although it was rarely the focal point of his activities. Only during compositi the brief period in 1702-3 when he was organist for the Cathedral in Cardinal ( Halle did he hold a church job which required regular weekly duties and, one of FIi since the cathedral congregation was Calvinist, these duties did not Several m include composing much (if any) concerted music. Virtually all of his Esther (H\ sacred music was written for specific events and liturgies, and the choice moYemenr of Handel to compose these works was dictated by his connections with The Ror specific patrons. Handel's sacred music falls into groups of works which of Vespers were written for similar forces and occasions, and will be discussed in followed b terms of those groups in this chapter. or feast, ar During his period of study with Zachow in Halle Handel must have followed b written some music for services at the Marktkirche or the Cathedral, but porarl, Ro no examples survive.l His earliest extant work is the F major setting of chanted, br Psalm 113, Laudate pueri (H\41/ 236),2 for solo soprano and strings. The tradition o autograph is on a type of paper that was available in Hamburg, and he up-to-date may have -

The Zodiac: Comparison of the Ancient Greek Mythology and the Popular Romanian Beliefs

THE ZODIAC: COMPARISON OF THE ANCIENT GREEK MYTHOLOGY AND THE POPULAR ROMANIAN BELIEFS DOINA IONESCU *, FLORA ROVITHIS ** , ELENI ROVITHIS-LIVANIOU *** Abstract : This paper intends to draw a comparison between the ancient Greek Mythology and the Romanian folk beliefs for the Zodiac. So, after giving general information for the Zodiac, each one of the 12 zodiac signs is described. Besides, information is given for a few astronomical subjects of special interest, together with Romanian people believe and the description of Greek myths concerning them. Thus, after a thorough examination it is realized that: a) The Greek mythology offers an explanation for the consecration of each Zodiac sign, and even if this seems hyperbolic in almost most of the cases it was a solution for things not easily understood at that time; b) All these passed to the Romanians and influenced them a lot firstly by the ancient Greeks who had built colonies in the present Romania coasts as well as via commerce, and later via the Romans, and c) The Romanian beliefs for the Zodiac is also connected to their deep Orthodox religious character, with some references also to their history. Finally, a general discussion is made and some agricultural and navigator suggestions connected to Pleiades and Hyades are referred, too. Keywords : Zodiac, Greek, mythology, tradition, religion. PROLOGUE One of their first thoughts, or questions asked, by the primitive people had possibly to do with sky and stars because, when during the night it was very dark, all these lights above had certainly arose their interest. So, many ancient civilizations observed the stars as well as their movements in the sky. -

Liturgical Drama in Bach's St. Matthew Passion

Uri Golomb Liturgical drama in Bach’s St. Matthew Passion Bach’s two surviving Passions are often cited as evidence that he was perfectly capable of producing operatic masterpieces, had he chosen to devote his creative powers to this genre. This view clashes with the notion that church music ought to be calm and measured; indeed, Bach’s contract as Cantor of St. Thomas’s School in Leipzig stipulated: In order to preserve the good order in the churches, [he would] so arrange the music that it shall not last too long, and shall be of such nature as not to make an operatic impression, but rather incite the listeners to devotion. (New Bach Reader, p. 105) One could argue, however, that Bach was never entirely faithful to this pledge, and that in the St. Matthew Passion he came close to violating it entirely. This article explores the fusion of the liturgical and the dramatic in the St. Matthew Passion, viewing the work as the combination of two dramas: the story of Christ’s final hours, and the Christian believer’s response to this story. This is not, of course, the only viable approach to this masterpiece. The St. Matthew Passion is a complex, heterogeneous work, rich in musical and expressive detail yet also displaying an impressive unity across its vast dimensions. This article does not pretend to explore all the work’s aspects; it only provides an overview of one of its distinctive features. 1. The St. Matthew Passion and the Passion genre The Passion is a musical setting of the story of Christ’s arrest, trial and crucifixion, intended as an elaboration of the Gospel reading in the Easter liturgy. -

What Handel Taught the Viennese About the Trombone

291 What Handel Taught the Viennese about the Trombone David M. Guion Vienna became the musical capital of the world in the late eighteenth century, largely because its composers so successfully adapted and blended the best of the various national styles: German, Italian, French, and, yes, English. Handel’s oratorios were well known to the Viennese and very influential.1 His influence extended even to the way most of the greatest of them wrote trombone parts. It is well known that Viennese composers used the trombone extensively at a time when it was little used elsewhere in the world. While Fux, Caldara, and their contemporaries were using the trombone not only routinely to double the chorus in their liturgical music and sacred dramas, but also frequently as a solo instrument, composers elsewhere used it sparingly if at all. The trombone was virtually unknown in France. It had disappeared from German courts and was no longer automatically used by composers working in German towns. J.S. Bach used the trombone in only fifteen of his more than 200 extant cantatas. Trombonists were on the payroll of San Petronio in Bologna as late as 1729, apparently longer than in most major Italian churches, and in the town band (Concerto Palatino) until 1779. But they were available in England only between about 1738 and 1741. Handel called for them in Saul and Israel in Egypt. It is my contention that the influence of these two oratorios on Gluck and Haydn changed the way Viennese composers wrote trombone parts. Fux, Caldara, and the generations that followed used trombones only in church music and oratorios. -

Brechin Bulletin Scottish Episcopal Church, Diocese of Brechin Newsletter

Brechin Bulletin Scottish Episcopal Church, Diocese of Brechin Newsletter. October 2010, No. 46 Scottish Charity No. SC 016813 FAREWELL EUCHARIST MAY THEY ALL BE ONE ON SATURDAY, 16TH OCTOBER IN The visit of Pope Benedict XVI to Scotland THE CATHEDRAL CHURCH OF ST. PAUL has passed off well. Even the weather was 12 noon fine. To mark Bishop John’s retirement Benedict XVI quoted some of the words used Clergy and Lay readers to robe in Alb and White Stole by John Paul II on his visit in 1982 (when the Refreshments will be served afterwards sun also shone on Bellahouston Park) which Donations towards a gift should be sent to the have been an inspiration to me in reflecting Bishop’s Office, Unit 14, Prospect III, Technology on Christ’s will that all His followers be one. Park, Gemini Crescent, Dundee. DD2 1SW by Thursday, 14th October. John Paul II said, “There is one Lord, one Please make cheques payable to: faith, one baptism……….We are only pilgrims The Diocese of Brechin. on this earth, making our way towards that CHURCH IN SOCIETY COMMITTEE heavenly kingdom promised to us as God’s A CELEBRATION OF VOLUNTEERING children. Beloved in Christ, for the future, Saturday, 16th October, 2010 can we not make that pilgrimage together 10.30am 3.30pm Venue: The Royal Ivy Hotel, Henderson hand in hand, bearing with each other Street, Bridge of Allan. FK9 4HG charitably, in complete selflessness, Purpose of the day: Celebration, Sharing, gentleness and patience, doing all we can to Advising, Developing, and Understanding. -

New College Bulletin 2017

New College Bulletin 2017 New College News Remembering Prof. Duncan Forrester Spotlight On Research Reading Matters In this issue… Contents This year’s New College Bulletin highlights the international scope of our students, staff, New College News 3 and activities. Deeply rooted in Edinburgh and In memoriam, Prof Duncan Forrester 6 Scottish history, New College is a centre of Staff, Student and Alumni news 8 excellence known for attracting students and supporters from around the world. Staff interview 12 Spotlight on Research: In the current year, we have students from all corners of the world including Ethiopia, Jordan, Cyprus, the Wode Psalter 14 Australia, United States of America, Canada, Italy, Reading matters: staff publications 16 England, Hungary, India, Scotland, Romania, Scholarships update 18 Netherlands, Cameroon, Hong Kong, China, Zimbabwe, France, Denmark, South Korea, Norway, Upcoming events 20 Indonesia, Taiwan, Sweden, Singapore, Brazil, Greece, Guatemala, Poland, Japan, Slovakia, and Switzerland. Many of you asked for interviews with academic and support staff. So, in this year’s Bulletin we hear from Dr Naomi Appleton, Senior Lecturer in Asian Religions. In the last couple of years, some of our major developments have been in the area of Science and Religion, which include both degree programmes and a more recent academic animal called a ‘MOOC’! We also feature information on our scholarships, which are increasingly important as fees and living costs continue to rise. As you’ll see elsewhere in these pages, we are able to offer a significant number of scholarships each year. Thanks to the ongoing philanthropic support of our alumni and supporters we have been able to grow existing scholarship funds and establish new ones. -

Handel's Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment By

Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Music in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Professor Mary Ann Smart Professor Emeritus John H. Roberts Professor George Haggerty, UC Riverside Professor Kevis Goodman Fall 2013 Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment Copyright 2013 by Jonathan Rhodes Lee ABSTRACT Virtue Rewarded: Handel’s Oratorios and the Culture of Sentiment by Jonathan Rhodes Lee Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Berkeley Professor Davitt Moroney, Chair Throughout the 1740s and early 1750s, Handel produced a dozen dramatic oratorios. These works and the people involved in their creation were part of a widespread culture of sentiment. This term encompasses the philosophers who praised an innate “moral sense,” the novelists who aimed to train morality by reducing audiences to tears, and the playwrights who sought (as Colley Cibber put it) to promote “the Interest and Honour of Virtue.” The oratorio, with its English libretti, moralizing lessons, and music that exerted profound effects on the sensibility of the British public, was the ideal vehicle for writers of sentimental persuasions. My dissertation explores how the pervasive sentimentalism in England, reaching first maturity right when Handel committed himself to the oratorio, influenced his last masterpieces as much as it did other artistic products of the mid- eighteenth century. When searching for relationships between music and sentimentalism, historians have logically started with literary influences, from direct transferences, such as operatic settings of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela, to indirect ones, such as the model that the Pamela character served for the Ninas, Cecchinas, and other garden girls of late eighteenth-century opera. -

![Prints and Johan Wittert Van Der Aa in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.[7] Drawings, Inv](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4834/prints-and-johan-wittert-van-der-aa-in-the-rijksmuseum-in-amsterdam-7-drawings-inv-254834.webp)

Prints and Johan Wittert Van Der Aa in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.[7] Drawings, Inv

Esther before Ahasuerus ca. 1640–45 oil on panel Jan Adriaensz van Staveren 86.7 x 75.2 cm (Leiden 1613/14 – 1669 Leiden) signed in light paint along angel’s shield on armrest of king’s throne: “JOHANNES STAVEREN 1(6?)(??)” JvS-100 © 2021 The Leiden Collection Esther before Ahasuerus Page 2 of 9 How to cite Van Tuinen, Ilona. “Esther before Ahasuerus” (2017). In The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 3rd ed. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Lara Yeager-Crasselt. New York, 2020–. https://theleidencollection.com/artwork/esther-before-ahasuerus/ (accessed October 02, 2021). A PDF of every version of this entry is available in this Online Catalogue's Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. © 2021 The Leiden Collection Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Esther before Ahasuerus Page 3 of 9 During the Babylonian captivity of the Jews, the beautiful Jewish orphan Comparative Figures Esther, heroine of the Old Testament Book of Esther, won the heart of the austere Persian king Ahasuerus and became his wife (Esther 2:17). Esther had been raised by her cousin Mordecai, who made Esther swear that she would keep her Jewish identity a secret from her husband. However, when Ahasuerus appointed as his minister the anti-Semite Haman, who issued a decree to kill all Jews, Mordecai begged Esther to reveal her Jewish heritage to Ahasuerus and plead for the lives of her people. Esther agreed, saying to Mordecai: “I will go to the king, even though it is against the law. -

Esther Nelson, Stanford Calderwood General

ESTHER NELSON, STANFORD CALDERWOOD GENERAL & ARTISTIC DIRECTOR | DAVID ANGUS, MUSIC DIRECTOR | JOHN CONKLIN, ARTISTIC ADVISOR THE MISSION OF BOSTON LYRIC OPERA IS TO BUILD CURIOSITY, ENTHUSIASM AND SUPPORT FOR OPERA BY CREATING MUSICALLY AND THEATRICALLY COMPELLING PRODUCTIONS, EVENTS, AND EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES FOR THE BOSTON COMMUNITY AND BEYOND. B | BOSTON LYRIC OPERA OVERVIEW: ANNUAL REPORT 2017 WELCOME Dear Patrons, Art is often inspired by the idea of a journey. Boston Lyric Opera’s 40TH Anniversary Season was a journey from Season opener to Season closer, with surprising and enlightening stories along the way, lessons learned, and strengths found. Together with you, we embraced the unexpected, and our organization was left stronger as a result. Our first year of producing works in multiple theaters was thrilling and eye-opening. REPORT Operas were staged in several of Boston’s best houses and uniformly received blockbuster reviews. We made an asset of being nimble, seizing upon the opportunity CONTENTS of our Anniversary Season to create and celebrate opera across our community. Best of all, our journey brought us closer than ever to our audiences. Welcome 1 It’s no coincidence that the 2016/17 Season opened with Calixto Bieito’s renowned 2016/17 Season: By the Numbers 2 staging of Carmen, in co-production with San Francisco Opera. The strong-willed gypsy Leadership & Staff 3 woman and the itinerant community she adopted was a perfect metaphor for our first production on the road. Bringing opera back to the Boston Opera House was an iconic 40TH Anniversary Kickoff 4 moment. Not only did Carmen become the Company’s biggest-selling show ever, it also Carmen 6 ignited a buzz around the community that drew a younger, more diverse audience.