Katherine Anne Porter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

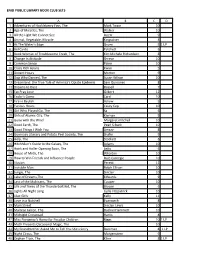

Web Book Club Sets

ENID PUBLIC LIBRARY BOOK CLUB SETS A B C D 1 Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Mark Twain 10 2 Age of Miracles, The Walker 10 3 All the Light We Cannot See Doerr 9 4 Animal, Vegetable, Miracle Kingsolver 4 5 At The Water's Edge Gruen 5 1 LP 6 Bel Canto Patchett 6 7 Book Woman of Troublesome Creek, The Kim Michele Richardson 8 8 Change in Attitude Shreve 10 9 Common Sense Paine 10 10 Crazy Rich Asians Kwan 5 11 Distant Hours Morton 9 12 Dog Who Danced, The Susan Wilson 10 13 Dreamland: the True Tale of America's Opiate Epidemic Sam Quinones 8 14 Dreams to Dust Russell 7 15 Eat Pray Love Gilbert 12 16 Ender's Game Card 10 17 Fire in Beulah Askew 5 18 Furious Hours Casey Cep 10 19 Girl Who Played Go, The Sa 6 20 Girls of Atomic City, The Kiernan 9 21 Gone with the Wind Margaret mitchell 10 22 Good Earth, The Pearl S Buck 10 23 Good Things I Wish You Amsay 8 24 Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Society, The Shafer 9 25 Help, The Stockett 6 26 Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, The Adams 10 27 Honk and Holler Opening Soon, The Letts 6 28 House of Mirth, The Wharton 10 29 How to Win Friends and Influence People Dale Carnegie 10 30 Illusion Peretti 12 31 Invisible Man Ralph Ellison 10 32 Jungle, The Sinclair 10 33 Lake of Dreams,The Edwards 9 34 Last of the Mohicans, The Cooper 10 35 Life and Times of the Thunderbolt Kid, The Bryson 6 36 Lights All Night Long Lydia Fitzpatrick 10 37 Lilac Girls Kelly 11 38 Love in a Nutshell Evanovich 8 39 Main Street Sinclair Lewis 10 40 Maltese Falcon, The Dashiel Hammett 10 41 Midnight Crossroad Harris 8 -

Wallace Stegner and the De-Mythologizing of the American West" (2004)

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - Department of Professional Department of Professional Studies Studies 2004 Angling for Repose: Wallace Stegner and the De- Mythologizing of the American West Jennie A. Harrop George Fox University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/dps_fac Recommended Citation Harrop, Jennie A., "Angling for Repose: Wallace Stegner and the De-Mythologizing of the American West" (2004). Faculty Publications - Department of Professional Studies. Paper 5. http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/dps_fac/5 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Professional Studies at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications - Department of Professional Studies by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANGLING FOR REPOSE: WALLACE STEGNER AND THE DE-MYTHOLOGIZING OF THE AMERICAN WEST A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of Arts and Humanities University of Denver In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Jennie A. Camp June 2004 Advisor: Dr. Margaret Earley Whitt Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ©Copyright by Jennie A. Camp 2004 All Rights Reserved Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. GRADUATE STUDIES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF DENVER Upon the recommendation of the chairperson of the Department of English this dissertation is hereby accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Profess^inJ charge of dissertation Vice Provost for Graduate Studies / if H Date Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Being Humble and Enduring Enough”

”Being Humble and Enduring Enough” An exploration of The Hunter’s Place in Nature In William Faulkner’s Go Down, Moses By Magnus Nerhovde Master’s Thesis Department of Foreign Languages University of Bergen May 2016 Samandrag Denne oppgåva er interessert i å undersøke korleis stad, natur og jakt blir brukt i boka Go Down, Moses av William Faulkner. Til dette formålet kjem eg til å nytta eit utval historiar frå boka, nemleg ”The Old People”, ”The Bear” og ”Delta Autumn”. Eg kjem til å dele oppgåva inn i tre kapitlar, og det vil væra eit tyngande fokus på karakteren Isaac ’Ike’ McCaslin. I det første kapittelet vil eg gjennom ein lesnad av desse historia undersøkje korleis ein byggjar opp ein god kjensle av stad i fiksjon, i tillegg til at eg ser på korleis Faulkner sjølv oppnår dette. I det andre kapittelet vil eg undersøke korleis Faulkner brukar natur i historia hans, og korleis natur kan nyttast for å gjere greie for kva rolle Faulkner sine karakterar har i historia og mellom kvarandre. Eit viktig spørsmål er korleis dei motseiande holdningane til naturvern og naturbruk har ein innverknad på karakterane. Til slutt vil eg fokusera på jakt og kva rolle jakt har i historia. Eg vil her blant anna undersøka i kor stor grad det er ”rett” at jegarane i historia jaktar på ”Old Ben”, den største og eldste bjørnen i skogen. Eit spesielt fokus vil væra korleis måten dei ulike karakterane jaktar på kan væra med på å beskrive deira forhold til natur. Den overhengande forståelsen er at ein må ha ein god tilknytning og forhold til naturen for å kunne væra ein jegar i Faulkner sine skogar, og at rollane til karakterane er i stor grad avhengig av deira tilknytning til naturen. -

The Ghostwriter

Van Damme 1 Karen Van Damme Dr. Leen Maes Master thesis English literature 30 July 2008 The evolution of Nathan Zuckerman in Philip Roth’s The Ghost Writer and Exit Ghost. 0. Introduction I was introduced to Philip Roth and the compelling voice of his fiction during a series of lectures on the topic of Jewish-American authors by Prof. Dr. Versluys in 2006 at Ghent University. The Counterlife (1986) was one of the novels on the reading list, in which I encountered for the first time his famous protagonist, Nathan Zuckerman. Ever since I have read this novel, I have been intrigued by Roth‟s work. My introduction to Jewish-American writing has made a lasting impression through him, which is why the choice was an easy one to make when we were asked to select a topic for this master thesis. I will not be dealing with Philip Roth‟s whole oeuvre, since the man is such a prolific writer and his work is in title to a thorough discussion. I will write about the first and the last novel in his Zuckerman-series, namely The Ghost Writer (1979) and Exit Ghost (2007). Nathan Zuckerman can be seen as Roth‟s alter-ego, an American- Jewish writer with a sharp pen. Since I have, unfortunately, only had the opportunity to read four of the eight Zuckerman-novels, I want to make it absolutely clear that the two novels mentioned here will be the sole basis for my analysis of the story-line and the character named Nathan Zuckerman. -

Banned & Challenged Classics

26. Gone with the Wind, 26. Gone with the Wind, by Margaret Mitchell by Margaret Mitchell 27. Native Son, by Richard Wright 27. Native Son, by Richard Wright Banned & Banned & 28. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, 28. One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Challenged Challenged by Ken Kesey by Ken Kesey 29. 29. Slaughterhouse-Five, 29. 29. Slaughterhouse-Five, Classics Classics by Kurt Vonnegut by Kurt Vonnegut 30. For Whom the Bell Tolls, 30. For Whom the Bell Tolls, by Ernest Hemingway by Ernest Hemingway 33. The Call of the Wild, 33. The Call of the Wild, The titles below represent banned or The titles below represent banned or by Jack London by Jack London challenged books on the Radcliffe challenged books on the Radcliffe 36. Go Tell it on the Mountain, 36. Go Tell it on the Mountain, Publishing Course Top 100 Novels of Publishing Course Top 100 Novels of by James Baldwin by James Baldwin the 20th Century list: the 20th Century list: 38. All the King's Men, 38. All the King's Men, 1. The Great Gatsby, 1. The Great Gatsby, by Robert Penn Warren by Robert Penn Warren by F. Scott Fitzgerald by F. Scott Fitzgerald 40. The Lord of the Rings, 40. The Lord of the Rings, 2. The Catcher in the Rye, 2. The Catcher in the Rye, by J.R.R. Tolkien by J.R.R. Tolkien by J.D. Salinger by J.D. Salinger 45. The Jungle, by Upton Sinclair 45. The Jungle, by Upton Sinclair 3. The Grapes of Wrath, 3. -

Reaching Across the Color Line: Margaret Mitchell and Benjamin Mays, an Uncommon Friendship

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Department of Middle-Secondary Education and Middle-Secondary Education and Instructional Instructional Technology (no new uploads as of Technology Faculty Publications Jan. 2015) 2013 Reaching Across the Color Line: Margaret Mitchell and Benjamin Mays, an Uncommon Friendship Jearl Nix Chara Haeussler Bohan Georgia State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/msit_facpub Part of the Elementary and Middle and Secondary Education Administration Commons, Instructional Media Design Commons, Junior High, Intermediate, Middle School Education and Teaching Commons, and the Secondary Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Nix, J. & Bohan, C. H. (2013). Reaching across the color line: Margaret Mitchell and Benjamin Mays, an uncommon friendship. Social Education, 77(3), 127–131. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Middle-Secondary Education and Instructional Technology (no new uploads as of Jan. 2015) at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Middle-Secondary Education and Instructional Technology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Social Education 77(3), pp 127–131 ©2013 National Council for the Social Studies Reaching across the Color Line: Margaret Mitchell and Benjamin Mays, an Uncommon Friendship Jearl Nix and Chara Haeussler Bohan In 1940, Atlanta was a bustling town. It was still dazzling from the glow of the previous In Atlanta, the color line was clearly year’s star-studded premiere of Gone with the Wind. The city purchased more and drawn between black and white citizens. -

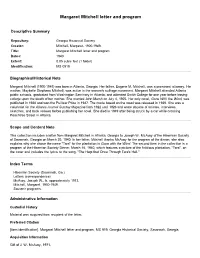

Margaret Mitchell Letter and Program

Margaret Mitchell letter and program Descriptive Summary Repository: Georgia Historical Society Creator: Mitchell, Margaret, 1900-1949. Title: Margaret Mitchell letter and program Dates: 1940 Extent: 0.05 cubic feet (1 folder) Identification: MS 0919 Biographical/Historical Note Margaret Mitchell (1900-1949) was born in Atlanta, Georgia. Her father, Eugene M. Mitchell, was a prominent attorney. Her mother, Maybelle Stephens Mitchell, was active in the women's suffrage movement. Margaret Mitchell attended Atlanta public schools, graduated from Washington Seminary in Atlanta, and attended Smith College for one year before leaving college upon the death of her mother. She married John Marsh on July 4, 1925. Her only novel, Gone With the Wind, was published in 1936 and won the Pulitzer Prize in 1937. The movie based on the novel was released in 1939. She was a columnist for the Atlanta Journal Sunday Magazine from 1922 until 1926 and wrote dozens of articles, interviews, sketches, and book reviews before publishing her novel. She died in 1949 after being struck by a car while crossing Peachtree Street in Atlanta. Scope and Content Note This collection includes a letter from Margaret Mitchell in Atlanta, Georgia to Joseph W. McAvoy of the Hibernian Society of Savannah, Georgia on March 20, 1940. In her letter, Mitchell thanks McAvoy for the program of the dinner; she also explains why she chose the name "Tara" for the plantation in Gone with the Wind. The second item in the collection is a program of the Hibernian Society Dinner, March 16, 1940, which features a picture of the fictitious plantation, "Tara", on the cover and includes the lyrics to the song, "The Harp that Once Through Tara's Hall." Index Terms Hibernian Society (Savannah, Ga.) Letters (correspondence) McAvoy, Joseph W., b. -

“Best Books of the Century”

19. The Hobbit 40. The Little Prince “BEST BOOKS J.R.R. Tolkien Antoine de Saint-Exupery OF THE CENTURY” 20. Number the Stars Lois Lowry 41. The World According to Garp 21. Slaughterhouse-Five John Irving Kurt Vonnegut 42. A Farewell to Arms 22. Ulysses Ernest Hemingway James Joyce 43. The Fountainhead 23. For Whom the Bell Tolls Ayn Rand Ernest Hemingway 44. Hatchet 24. Harold and the Purple Gary Paulsen Crayon Crockett Johnson 45. The Lion, the Witch & the Wardrobe 25. Invisible Man C.S. Lewis Ralph Ellison 46. Lolita 26. The Lord of the Rings Vladimir Nabokov Northport-East Northport Public Library Trilogy J.R.R. Tolkien 47. Of Human Bondage 1999 W. Somerset Maugham Main Reading Room 27. Anne of Green Gables L.M. Montgomery 48. The Sound and the Fury In the spring of 1999, the Library Trustees commissioned William Faulkner Northport sculptor George W. Hart to create The Millennium 28. Beloved Bookball. This complex spherical arrangement of 60 Toni Morrison 49. Where the Red Fern Grows interlocking books is suspended from the ceiling of the Wilson Rawls 29. Where the Sidewalk Main Reading Room of the Northport Library. Each book Ends 50. An American Tragedy is engraved with the title and author of one of the “Best Shel Silverstein Theodore Dreiser Books of the Century” as selected by community members. This unique and beautiful work of art was funded, in 30. Charlie and the 51. Brave New World Chocolate Factory Aldous Huxley part, through generous donations from community residents Roald Dahl whose names are engraved on a plaque in Northport’s 52. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction Honors a Distinguished Work of Fiction by an American Author, Preferably Dealing with American Life

Pulitzer Prize Winners Named after Hungarian newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer, the Pulitzer Prize for fiction honors a distinguished work of fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life. Chosen from a selection of 800 titles by five letter juries since 1918, the award has become one of the most prestigious awards in America for fiction. Holdings found in the library are featured in red. 2017 The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead 2016 The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen 2015 All the Light we Cannot See by Anthony Doerr 2014 The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt 2013: The Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson 2012: No prize (no majority vote reached) 2011: A visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 2010:Tinkers by Paul Harding 2009:Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 2008:The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 2007:The Road by Cormac McCarthy 2006:March by Geraldine Brooks 2005 Gilead: A Novel, by Marilynne Robinson 2004 The Known World by Edward Jones 2003 Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2002 Empire Falls by Richard Russo 2001 The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon 2000 Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri 1999 The Hours by Michael Cunningham 1998 American Pastoral by Philip Roth 1997 Martin Dressler: The Tale of an American Dreamer by Stephan Milhauser 1996 Independence Day by Richard Ford 1995 The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields 1994 The Shipping News by E. Anne Proulx 1993 A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain by Robert Olen Butler 1992 A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley -

SUMMER READING ASSIGNMENT English 11 VITAL INFORMATION: 1. Choose One Novel to Read from This List Below: the Sound And

SUMMER READING ASSIGNMENT English 11 VITAL INFORMATION: 1. Choose one novel to read from this list below: The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner My Antonia by Willa Cather House of the Seven Gables by Nathaniel Hawthorne The Bell Jar by Sylvia Plath Gone With the Wind by Margaret Mitchell The Legend of Sleepy Hollow by Washington Irving Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison The Awakening by Kate Chopin The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain Coming Back Stronger: Unleashing the Power of Adversity by Drew Brees A Farewell To Arms by Ernest Hemingway This Side of Paradise by F. Scott Fitzgerald 2. Complete Two of the following five options from the assignment packet: Assignment 1: Reading Vocabulary Assignment 2: Plot Assignment 3: Connections (Do not use the same “connection” for all answers. For example, if you use a “life experience” for two connections, choose a book or movie for the third.) Assignment 4: Book Review 3. Assignments are due by the first day of school. 4. The summer reading assignment will be counted as a daily and quiz grade for Q1. 5. Staple all your entries for the book together before you turn them in. HELPFUL HINTS: An easy way to prepare for these assessments is to answer the questions as you read or annotate your book with sticky notes or highlighters. If you do this, you will not have to go searching for the information you read a few weeks prior to starting the project. To earn full credit for each answer, you must use grammatically correct and structurally sound sentences, as well as detailed answers and specific examples from the books. -

Why Atlanta for the Permanent Things?

Atlanta and The Permanent Things William F. Campbell, Secretary, The Philadelphia Society Part One: Gone With the Wind The Regional Meetings of The Philadelphia Society are linked to particular places. The themes of the meeting are part of the significance of the location in which we are meeting. The purpose of these notes is to make our members and guests aware of the surroundings of the meeting. This year we are blessed with the city of Atlanta, the state of Georgia, and in particular The Georgian Terrace Hotel. Our hotel is filled with significant history. An overall history of the hotel is found online: http://www.thegeorgianterrace.com/explore-hotel/ Margaret Mitchell’s first presentation of the draft of her book was given to a publisher in the Georgian Terrace in 1935. Margaret Mitchell’s house and library is close to the hotel. It is about a half-mile walk (20 minutes) from the hotel. http://www.margaretmitchellhouse.com/ A good PBS show on “American Masters” provides an interesting view of Margaret Mitchell, “American Rebel”; it can be found on your Roku or other streaming devices: http://www.wgbh.org/programs/American-Masters-56/episodes/Margaret-Mitchell- American-Rebel-36037 The most important day in hotel history was the premiere showing of Gone with the Wind in 1939. Hollywood stars such as Clark Gable, Carole Lombard, and Olivia de Haviland stayed in the hotel. Although Vivien Leigh and her lover, Lawrence Olivier, stayed elsewhere they joined the rest for the pre-Premiere party at the hotel. Our meeting will be deliberating whether the Permanent Things—Truth, Beauty, and Virtue—are in fact, permanent, or have they gone with the wind? In the movie version of Gone with the Wind, the opening title card read: “There was a land of Cavaliers and Cotton Fields called the Old South..