Redalyc.BASALTIC EXPLOSIVE VOLCANISM in a TUFF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

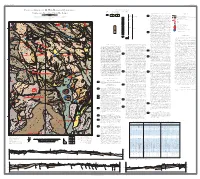

Geologic Map of the Central San Juan Caldera Cluster, Southwestern Colorado by Peter W

Geologic Map of the Central San Juan Caldera Cluster, Southwestern Colorado By Peter W. Lipman Pamphlet to accompany Geologic Investigations Series I–2799 dacite Ceobolla Creek Tuff Nelson Mountain Tuff, rhyolite Rat Creek Tuff, dacite Cebolla Creek Tuff Rat Creek Tuff, rhyolite Wheeler Geologic Monument (Half Moon Pass quadrangle) provides exceptional exposures of three outflow tuff sheets erupted from the San Luis caldera complex. Lowest sheet is Rat Creek Tuff, which is nonwelded throughout but grades upward from light-tan rhyolite (~74% SiO2) into pale brown dacite (~66% SiO2) that contains sparse dark-brown andesitic scoria. Distinctive hornblende-rich middle Cebolla Creek Tuff contains basal surge beds, overlain by vitrophyre of uniform mafic dacite that becomes less welded upward. Uppermost Nelson Mountain Tuff consists of nonwelded to weakly welded, crystal-poor rhyolite, which grades upward to a densely welded caprock of crystal-rich dacite (~68% SiO2). White arrows show contacts between outflow units. 2006 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey CONTENTS Geologic setting . 1 Volcanism . 1 Structure . 2 Methods of study . 3 Description of map units . 4 Surficial deposits . 4 Glacial deposits . 4 Postcaldera volcanic rocks . 4 Hinsdale Formation . 4 Los Pinos Formation . 5 Oligocene volcanic rocks . 5 Rocks of the Creede Caldera cycle . 5 Creede Formation . 5 Fisher Dacite . 5 Snowshoe Mountain Tuff . 6 Rocks of the San Luis caldera complex . 7 Rocks of the Nelson Mountain caldera cycle . 7 Rocks of the Cebolla Creek caldera cycle . 9 Rocks of the Rat Creek caldera cycle . 10 Lava flows premonitory(?) to San Luis caldera complex . .11 Rocks of the South River caldera cycle . -

Los Morados Scoria Cone, Mendoza, Argentina

Cent. Eur. J. Geosci. • 3(2) • 2011 • 102-118 DOI: 10.2478/s13533-011-0008-4 Central European Journal of Geosciences The role of collapsing and cone rafting on eruption style changes and final cone morphology: Los Morados scoria cone, Mendoza, Argentina Research Article Karoly Németh1, Corina Risso2, Francisco Nullo3, Gabor Kereszturi1,4 1 Volcanic Risk Solutions, Massey University, Private Bag 11 222, Palmerston North, New Zealand 2 Departamento de Geología , Area Riesgo Volcánico, FCEyN-Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina 3 CONICET-SEGEMAR, Buenos Aires, Argentina 4 Geological Institute of Hungary, Stefánia út 14, Budapest, 1143, Hungary Received 30 November 2010; accepted 31 January 2011 Abstract: Payún Matru Volcanic Field is a Quaternary monogenetic volcanic field that hosts scoria cones with perfect to breached morphologies. Los Morados complex is a group of at least four closely spaced scoria cones (Los Morados main cone and the older Cones A, B, and C). Los Morados main cone was formed by a long lived eruption of months to years. After an initial Hawaiian-style stage, the eruption changed to a normal Strombolian, cone- building style, forming a cone over 150 metres high on a northward dipping (∼4˚) surface. An initial cone gradually grew until a lava flow breached the cone’s base and rafted an estimated 10% of the total volume. A sudden sector collapse initiated a dramatic decompression in the upper part of the feeding conduit and triggered violent a Strombolian style eruptive stage. Subsequently, the eruption became more stable, and changed to a regular Strombolian style that partially rebuilt the cone. -

(2000), Voluminous Lava-Like Precursor to a Major Ash-Flow

Journal of Volcanology and Geothermal Research 98 (2000) 153–171 www.elsevier.nl/locate/jvolgeores Voluminous lava-like precursor to a major ash-flow tuff: low-column pyroclastic eruption of the Pagosa Peak Dacite, San Juan volcanic field, Colorado O. Bachmanna,*, M.A. Dungana, P.W. Lipmanb aSection des Sciences de la Terre de l’Universite´ de Gene`ve, 13, Rue des Maraıˆchers, 1211 Geneva 4, Switzerland bUS Geological Survey, 345 Middlefield Rd, Menlo Park, CA, USA Received 26 May 1999; received in revised form 8 November 1999; accepted 8 November 1999 Abstract The Pagosa Peak Dacite is an unusual pyroclastic deposit that immediately predated eruption of the enormous Fish Canyon Tuff (ϳ5000 km3) from the La Garita caldera at 28 Ma. The Pagosa Peak Dacite is thick (to 1 km), voluminous (Ͼ200 km3), and has a high aspect ratio (1:50) similar to those of silicic lava flows. It contains a high proportion (40–60%) of juvenile clasts (to 3–4 m) emplaced as viscous magma that was less vesiculated than typical pumice. Accidental lithic fragments are absent above the basal 5–10% of the unit. Thick densely welded proximal deposits flowed rheomorphically due to gravitational spreading, despite the very high viscosity of the crystal-rich magma, resulting in a macroscopic appearance similar to flow- layered silicic lava. Although it is a separate depositional unit, the Pagosa Peak Dacite is indistinguishable from the overlying Fish Canyon Tuff in bulk-rock chemistry, phenocryst compositions, and 40Ar/39Ar age. The unusual characteristics of this deposit are interpreted as consequences of eruption by low-column pyroclastic fountaining and lateral transport as dense, poorly inflated pyroclastic flows. -

Source to Surface Model of Monogenetic Volcanism: a Critical Review

Downloaded from http://sp.lyellcollection.org/ by guest on September 28, 2021 Source to surface model of monogenetic volcanism: a critical review I. E. M. SMITH1 &K.NE´ METH2* 1School of Environment, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand 2Volcanic Risk Solutions, Massey University, Palmerston North 4442, New Zealand *Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Small-scale volcanic systems are the most widespread type of volcanism on Earth and occur in all of the main tectonic settings. Most commonly, these systems erupt basaltic magmas within a wide compositional range from strongly silica undersaturated to saturated and oversatu- rated; less commonly, the spectrum includes more siliceous compositions. Small-scale volcanic systems are commonly monogenetic in the sense that they are represented at the Earth’s surface by fields of small volcanoes, each the product of a temporally restricted eruption of a composition- ally distinct batch of magma, and this is in contrast to polygenetic systems characterized by rela- tively large edifices built by multiple eruptions over longer periods of time involving magmas with diverse origins. Eruption styles of small-scale volcanoes range from pyroclastic to effusive, and are strongly controlled by the relative influence of the characteristics of the magmatic system and the surface environment. Gold Open Access: This article is published under the terms of the CC-BY 3.0 license. Small-scale basaltic magmatic systems characteris- hazards associated with eruptions, and this is tically occur at the Earth’s surface as fields of small particularly true where volcanic fields are in close monogenetic volcanoes. These volcanoes are the proximity to population centres. -

Rhyolite and Trachyte Formation at Lake City Caldera: Insight from Quantitative Textural and Geochemical Analyses

Michigan Technological University Digital Commons @ Michigan Tech Dissertations, Master's Theses and Master's Reports 2016 Rhyolite and Trachyte Formation at Lake City Caldera: Insight from Quantitative Textural and Geochemical Analyses Jordan Lubbers Michigan Technological University, [email protected] Copyright 2016 Jordan Lubbers Recommended Citation Lubbers, Jordan, "Rhyolite and Trachyte Formation at Lake City Caldera: Insight from Quantitative Textural and Geochemical Analyses", Open Access Master's Thesis, Michigan Technological University, 2016. https://doi.org/10.37099/mtu.dc.etdr/99 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.mtu.edu/etdr Part of the Geochemistry Commons, and the Geology Commons RHYOLITE AND TRACHYTE FORMATION AT LAKE CITY CALDERA: INSIGHT FROM QUANTITATIVE TEXTURAL AND GEOCHEMICAL ANALYSES By Jordan E. Lubbers A THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE In Geology MICHIGAN TECHNOLOGICAL UNIVERSITY 2016 © 2016 Jordan E. Lubbers This thesis has been approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in Geology. Geological and Mining Engineering and Sciences ThesisDepartment Advisor: ofChad Deering Committee Member: Olivier Bachmann Committee Member: William Rose Department Chair: John Gierke Table of Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................................. 6 Abstract ...................................................................................................................................................................... -

Volcanoes a to Z

Mount St Helens National Volcanic Monument – Teacher’s Corner -Teacher Info. Gifford Pinchot National Forest USDA Forest Service Volcanoes A to Z – Bus Activity Time Requirement: all day Exhibit / Trail Used: all exhibits/trails visited Locations: all locations visited, review on the bus en route back to your school. This activity is to be completed throughout the day and between other activities. Students will make note of key words while reading exhibits, interpretive signs, or labels, or by hearing them from each other, their teacher, movies or rangers. Consider distributing on the bus and collecting on the bus. Goal: 1) The student will become familiar with terminology related to the study of volcanoes, geology, or the ecosystems that surround them. Objectives: 1) The student will listen attentively. 2) The student will recall and list vocabulary words for things and concepts encountered on a field trip to Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument. 3) The student will distinguish nouns from other parts of speech. WASHINGTON EALRS and OREGON BENCHMARK STANDARDS Washington Social Studies 2.0- The student understands the complex physical and human characteristics of places and regions. Geography 2.1- Describe the natural characteristics of places and regions. Science 4.2 Use writing and speaking skills to organize and express science ideas. a. Use science vocabulary appropriately in written explanations, conversations and verbal presentations. Oregon Science-CCG The Dynamic Earth- Understand the properties and limited availability of the materials which make up the Earth. BM1- Recognize physical differences in Earth materials. Language-CCG Select functional, precise, and descriptive words appropriate to audience and purpose. -

Geologic Map of the Mchan Reservoir Quadrangle, Camas and Gooding

IDAHO GEOLOGICAL SURVEY DIGITAL WEB MAP 116 MOSCOW-BOISE-POCATELLO WWW.IDAHOGEOLOGY.ORG KAUFFMAN, OTHBERG, AND GARWOOD Disclaimer: This Digital Web Map is an informal report and may be CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE MCHAN RESERVOIR QUADRANGLE, revised and formally published at a later time. Its content and format may not conform to agency standards. Artificial Unconsolidated Sedimentary Volcanic Intrusive Deposits and Mass Movement Deposits Rocks Rocks Alluvial Mass Movement CAMAS AND GOODING COUNTIES, IDAHO Deposits Deposits phy with common hoodoo cliffs and blocky slopes. Soils are generally thin SYMBOLS to absent. m Holocene Qas Qaf Qc Qls Tmh Basalt of McHan (Miocene)—Medium gray, fine- to medium-grained nearly Contact: dashed where approximately located. John D. Kauffman, Kurt L. Othberg, and Dean L. Garwood Pleistocene QUATERNARY aphyric to plagioclase-phyric basalt. Consists of one to three flows. Plagio- Qsch clase phenocrysts in the more phyric flows (or parts of a flow) range from Fault: bar and ball on downthrown side; dashed where inferred; 2-7 mm in length for individual crystals and 5-10 mm for glomerocrysts. unconformity dotted where concealed. Olivine is uncommon and typically <1 mm. Remanent magentic polarity is 2010 Tsma Pliocene probably reverse, although both normal, reverse, inconclusive, or inclina- Fold axis: arrow indicates direction of plunge. unconformity tion sensitive readings were obtained in the field. Thickness ranges from Trd less than 15 m (50 feet) to as much as 30 m (100 feet). Unconformably Anticline. A unconformity overlies Hash Spring sediments or Gwin Spring tuff where the sediments are Qc Tgs Tmh Thsg Thsg Tgs Tbcc absent. -

Dilemma of Geoconservation of Monogenetic Volcanic Sites Under Fast Urbanization and Infrastructure Developments with Special Re

sustainability Article Dilemma of Geoconservation of Monogenetic Volcanic Sites under Fast Urbanization and Infrastructure Developments with Special Relevance to the Auckland Volcanic Field, New Zealand Károly Németh 1,2,3,* , Ilmars Gravis 3 and Boglárka Németh 1 1 School of Agriculture and Environment, Massey University, Palmerston North 4442, New Zealand; [email protected] 2 Institute of Earth Physics and Space Science, 9400 Sopron, Hungary 3 The Geoconservation Trust Aotearoa, 52 Hukutaia Road, Op¯ otiki¯ 3122, New Zealand; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +64-27-4791484 Abstract: Geoheritage is an important aspect in developing workable strategies for natural hazard resilience. This is reflected in the UNESCO IGCP Project (# 692. Geoheritage for Geohazard Resilience) that continues to successfully develop global awareness of the multifaced aspects of geoheritage research. Geohazards form a great variety of natural phenomena that should be properly identified, and their importance communicated to all levels of society. This is especially the case in urban areas such as Auckland. The largest socio-economic urban center in New Zealand, Auckland faces potential volcanic hazards as it sits on an active Quaternary monogenetic volcanic field. Individual volcanic geosites of young eruptive products are considered to form the foundation of community Citation: Németh, K.; Gravis, I.; outreach demonstrating causes and consequences of volcanism associated volcanism. However, in Németh, B. Dilemma of recent decades, rapid urban development has increased demand for raw materials and encroached Geoconservation of Monogenetic on natural sites which would be ideal for such outreach. The dramatic loss of volcanic geoheritage Volcanic Sites under Fast of Auckland is alarming. -

Summary of Rock-Property Measurements for Hong Kong Tuff Samples

LBNL-58878 Summary of Rock-Property Measurements for Hong Kong Tuff Samples Patrick Dobson and Seiji Nakagawa Earth Sciences Division September 2005 LBNL-58878 Summary of Rock-Property Measurements for Hong Kong Tuff Samples Patrick Dobson and Seiji Nakagawa Earth Sciences Division Ernest Orlando Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory University of California Berkeley, California 94720 September 2005 This work was supported by the Director, Office of Science, Laboratory Directed Research and Development, of the U.S. Department of Energy under Contract No. DE-AC03-76SF00098. Summary A series of rock-property measurements was performed on a suite of rhyolitic tuff samples from the area above the Aberdeen Tunnel of Hong Kong. The goal of this study was to determine the mechanical properties of these samples after weathering. This report contains petrographic descriptions, porosity, bulk and grain density, as well as ultrasonic measurements, elastic modulii calculations, and rock-strength determinations. Variations in rock properties are related to alteration and the presence of fractures in the tuff. Granitic rocks located adjacent to the altered tuffs would be better candidates for underground excavations. Introduction Four rock samples received from Dr. Kam-Biu Luk (LBNL Physics Division) had previously been collected from the vicinity of the Aberdeen Tunnel on Hong Kong Island. The rock samples were obtained from surface outcrops rather than from the interior of the tunnel (the tunnel is most likely lined with cement, thus precluding sampling). Core plugs measuring 2.54 cm in diameter (1”) that were obtained from the hand samples were used for the rock-property measurements (Figure 1). Figure 1. -

The Sirte Basin Province of Libya—Sirte-Zelten Total Petroleum System

The Sirte Basin Province of Libya—Sirte-Zelten Total Petroleum System By Thomas S. Ahlbrandt U.S. Geological Survey Bulletin 2202–F U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior Gale A. Norton, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Charles G. Groat, Director Version 1.0, 2001 This publication is only available online at: http://geology.cr.usgs.gov/pub/bulletins/b2202-f/ Any use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government Manuscript approved for publication May 8, 2001 Published in the Central Region, Denver, Colorado Graphics by Susan M. Walden, Margarita V. Zyrianova Photocomposition by William Sowers Edited by L.M. Carter Contents Foreword ............................................................................................................................................... 1 Abstract................................................................................................................................................. 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 2 Acknowledgments............................................................................................................................... 2 Province Geology................................................................................................................................. 2 Province Boundary.................................................................................................................... -

The Kufrah Paleodrainage System in Libya: a Past Connection to the Mediterranean Sea? Philippe Paillou, Stephen Tooth, S

The Kufrah paleodrainage system in Libya: A past connection to the Mediterranean Sea? Philippe Paillou, Stephen Tooth, S. Lopez To cite this version: Philippe Paillou, Stephen Tooth, S. Lopez. The Kufrah paleodrainage system in Libya: A past connection to the Mediterranean Sea?. Comptes Rendus Géoscience, Elsevier Masson, 2012, 344 (8), pp.406-414. 10.1016/j.crte.2012.07.002. hal-00833333 HAL Id: hal-00833333 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00833333 Submitted on 12 Jun 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. *Manuscript / Manuscrit The Kufrah Paleodrainage System in Libya: 1 2 3 A Past Connection to the Mediterranean Sea ? 4 5 6 7 8 9 Le système paléo-hydrographique de Kufrah en Libye : 10 11 12 Une ancienne connexion avec la mer Méditerranée ? 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Philippe PAILLOU 21 22 Univ. Bordeaux, LAB,UMR 5804, F-33270, Floirac, France 23 24 Tel: +33 557 776 126 Fax: +33 557 776 110 25 26 27 E-mail: [email protected] 28 29 30 31 32 Stephen TOOTH 33 34 Institute of Geography and Earth Sciences, Aberystwyth University, Ceredigion, UK 35 36 37 38 39 Sylvia LOPEZ 40 41 42 Univ. -

Lecture 12: Volcanoes Read: Chapter 6 Homework #10 Due Thursday 12Pm

Learning Objectives (LO) Lecture 12: Volcanoes Read: Chapter 6 Homework #10 due Thursday 12pm What we’ll learn today:! 1. Define the term volcano and explain why geologists study volcanoes! 2. Compare and contrast 3 common types of magma! 3. Describe volcanic gases and the role they play in explosive vs effusive eruptions! 4. Identify what gives a shield volcano its distinctive shape! What is causing this eruption? What factors influence its character? “A volcano is any landform from which lava, gas, or ashes, escape from underground or have done so in the past.” From Chapter 5: magma (and lava) can be felsic, intermediate, or mafic. How does magma chemistry influence the nature of volcanic eruptions? Hawaiian Volcanism http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6J6X9PsAR5w Indonesian Volcanism http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5LzHpeVJQuE Viscosity Viscous: thick and sticky Low viscosity High viscosity Viscosity Magma Composition (Igneous Rocks) How does magma chemistry determine lava and eruption characteristics? Felsic Intermediate Mafic less Mg/Fe content more more Si/O content less The Major 7 Types of Igneous Rocks Seven major types of igneous rocks Rhyolite Andesite Basalt Extrusive Granite Diorite Gabbro Peridotite Texture Texture Intrusive Felsic Intermediate Mafic Ultramafic Composition The Rocks of Volcanoes Seven major types of igneous rocks Rhyolite Andesite Basalt Extrusive melt at melt at low temperature high temperature Felsic Intermediate Mafic Ultramafic Composition Three Common Types of Magma: BASALTIC ANDESITIC RHYOLITIC Three Common Types of Magma: BASALTIC Basaltic lava flows easily because of its low viscosity and low gas content. Aa - rough, fragmented lava blocks called “clinker” The low viscosity is due to low silica content.