F:\AAA Print This\Webberwalkingtogether2012

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 1: the Life and Times of John Owen 9

Christ Exhibited and the Covenant Confirmed: The Eucharistic Theology of John Owen John C. Bellingham, MDiv Faculty of Religious Studies McGill University, Montreal February 27, 2014 Submitted to the Faculty of Religious Studies at McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts There is a reception of Christ as tendered in the promise of the gospel; but here [in the Lord’s Supper] is a peculiar way of his exhibition under outward signs, and a mysterious reception of him in them, really, so as to come to a real substantial incorporation in our souls. This is that which believers ought to labour after an experience of in themselves; …. they submit to the authority of Jesus Christ in a peculiar manner, giving him the glory of his kingly office; mixing faith with him as dying and making atonement by his blood, so giving him the glory and honour of his priestly office; much considering the sacramental union that is, by his institution, between the outward signs and the thing signified, thus glorifying him in his prophetical office; and raising up their souls to a mysterious reception and incorporation of him, receiving him to dwell in them, warming, cherishing, comforting, and strengthening their hearts. – John Owen, DD, Sacramental Discourses XXV.4 ii Table of Contents Acknowledgments iv Abstract v Résumé vi Introduction: John Owen and the Lord’s Supper 1 Chapter 1: The Life and Times of John Owen 9 Chapter 2: John Owen’s Sixteenth Century Inheritance 35 Chapter 3: The Lord’s Supper in Reformed Orthodoxy 80 Chapter 4: John Owen’s Eucharistic Theology 96 Conclusion 133 Bibliography 137 iii Acknowledgments I would like to express my sincere appreciation to the following people without whom this project would not have been possible. -

Professional & Academic 2017 CATALOG Reliable. Credible

Professional & Academic CELEBRATING CONCORDIA PUBLISHING HOUSE 2017 CATALOG Reliable. Credible. Uniquely Lutheran. CPH.ORG NEW RELEASES PAGE 4 PAGE 9 PAGE 15 PAGE 17 PAGE 21 PAGE 29 PAGE 11 PAGE 10 PAGE 18 2 VISIT CPH.ORG FOR MORE INFORMATION 1-800-325-3040 FEATURED REFORMATION TITLES PAGE 12 PAGE 12 PAGE 25 PAGE 25 PAGE 25 PAGE 25 PAGE 26 PAGE 33 PAGE 7 @CPHACADEMIC CPH.ORG/ACADEMICBLOG 3 Concordia Commentary Series Forthcoming 2017 HEBREWS John W. Kleinig 2 SAMUEL Andrew E. Steinmann New ROMANS 9–16 Dr. Michael P. Middendorf (cph.org/michaelmiddendorf) is Professor of eology at Concordia University Irvine, California. Romans conveys the timeless truths of the Gospel to all people of all times and places. at very fact explains the tremendous impact the letter has had ever since it was rst written. In this letter, Paul conveys the essence of the Christian faith in a universal manner that has been cherished by believers—and challenged by unbelievers—perhaps more so than any other biblical book. In this commentary, you’ll nd the following: • Clear exposition of the Law and Gospel theology in Paul’s most comprehensive epistle • Passage a er passage of bene cial insight for preachers and biblical teachers who desire to be faithful to the text • An in-depth overview of the context, ow of Paul’s argument, and commonly discussed issues in each passage • Detailed textual notes on the Greek, with a well-reasoned explanation of the apostle’s message “ e thorough, thoughtful, and careful interaction with other interpreters of Romans and contemporary literature that runs through the commentary is truly excellent. -

Melanchthon Versus Luther: the Contemporary Struggle

CONCORDIA THEOLOGICAL QUARTERLY Volume 44, Numbers 2-3 --- - - - JULY 1980 Can the Lutheran Confessions Have Any Meaning 450 Years Later?.................... Robert D. Preus 104 Augustana VII and the Eclipse of Ecumenism ....................................... Sieg bert W. Becker 108 Melancht hon versus Luther: The Contemporary Struggle ......................... Bengt Hagglund 123 In-. Response to Bengt Hagglund: The importance of Epistemology for Luther's and Melanchthon's Theology .............. Wilbert H. Rosin 134 Did Luther and Melanchthon Agree on the Real Presence?.. ....................................... David P. Scaer 14 1 Luther and Melanchthon in America ................................................ C. George Fry 148 Luther's Contribution to the Augsburg Confession .............................................. Eugene F. Klug 155 Fanaticism as a Theological Category in the Lutheran Confessions ............................... Paul L. Maier 173 Homiletical Studies 182 Melanchthon versus Luther: the Contemporary Struggle Bengt Hagglund Luther and Melanchthon in Modern Research In many churches in Scandinavia or in Germany one will find two oil paintings of the same size and datingfrom the same time, representing Martin Luther and Philip Melanchthon, the two prime reformers of the Church. From the point of view of modern research it may seem strange that Melanchthon is placed on the same level as Luther, side by side with him, equal in importance and equally worth remembering as he. Their common achieve- ment was, above all, the renewal of the preaching of the Gospel, and therefore it is deserving t hat their portraits often are placed in the neighborhood of the pulpit. Such pairs of pictures were typical of the nineteenth-century view of Melanchthon and Luther as harmonious co-workers in the Reformation. These pic- tures were widely displayed not only in the churches, but also in many private homes in areas where the Reformation tradition was strong. -

Lutheran Spirituality and the Pastor

Lutheran Spirituality and the Pastor By Gaylin R. Schmeling I. The Devotional Writers and Lutheran Spirituality 2 A. History of Lutheran Spirituality 2 B. Baptism, the Foundation of Lutheran Spirituality 5 C. Mysticism and Mystical Union 9 D. Devotional Themes 11 E. Theology of the Cross 16 F. Comfort (Trost) of the Lord 17 II. The Aptitude of a Seelsorger and Spiritual Formation 19 A. Oratio: Prayer and Spiritual Formation 20 B. Meditatio: Meditation and Spiritual Formation 21 C. Tentatio: Affliction and Spiritual Formation 21 III. Proper Lutheran Meditation 22 A. Presuppositions of Meditation 22 B. False Views of Meditation 23 C. Outline of Lutheran Meditation 24 IV. Meditation on the Psalms 25 V. Conclusion 27 G.R. Schmeling Lutheran Spirituality 2 And the Pastor Lutheran Spirituality and the Pastor I. The Devotional Writers and Lutheran Spirituality The heart of Lutheran spirituality is found in Luther’s famous axiom Oratio, Meditatio, Tentatio (prayer, meditation, and affliction). The one who has been declared righteous through faith in Christ the crucified and who has died and rose in Baptism will, as the psalmist says, “delight … in the Law of the Lord and in His Law he meditates day and night” (Psalm 1:2). He will read, mark, learn, and take the Word to heart. Luther writes concerning meditation on the Biblical truths in the preface of the Large Catechism, “In such reading, conversation, and meditation the Holy Spirit is present and bestows ever new and greater light and devotion, so that it tastes better and better and is digested, as Christ also promises in Matthew 18[:20].”1 Through the Word and Sacraments the entire Trinity makes its dwelling in us and we have union and communion with the divine and are conformed to the image of Christ (Romans 8:29; Colossians 3:10). -

Life of Philip Melanchthon

NYPL RESEARCH LIBRARIES 3 3433 08235070 7 Life of MELANciTHON m M \ \ . A V. Phu^ji' Mklanchthon. LIFE PHILIP MELAXCHTHOX. Rev. JOSEPH STUMP. A.M., WITH AN IXTKCDCCTIOS BY Rev. G. F. SPIEKER. D.D., /V<jri-iVi.»r .-.-" Cj:»r.-i ~':'sT:.'>y r* sAt LtttkiT^itJt TianiJgiir^ Smtimtry at /LLirSTRATED. Secoxp Epitiox. PILGER PUBLISHING HOUSE READING, PA. XEW YORK. I S g ;. TEE MEW YORK P'REFACE. The life of so distinguished a servant of God as Me- lanchthon deserves to be better known to the general reader than it actually is. In the great Reformation of the sixteenth century, his work stands second to that of Luther alone. Yet his life is comparatively unknown to many intelligent Christians. In view of the approaching four hundredth anni- versary of Melanchthon's birth, this humble tribute to his memory is respectfully offered to the public. It is the design of these pages, by the presentation of the known facts in Melanchthon's career and of suitable extracts from his writings, to give a truthful picture of his life, character and work. In the preparation of this book, the author has made use of a number of r^ biographies of ]\Ielanchthon by German authors, and of such other sources of information as were accessi- ble to him. His aim has been to prepare a brief but sufficiently comprehensive life of Melanchthon, in such a form as would interest the people. To what extent he has succeeded in his undertaking, others must judge. (V) That these pages may, in some measure at least, ac- complish their purpose, and make the Christian reader more familiar with the work and merit of the man of God whom they endeavor to portray, is the sincere wish of Thern Author.A CONTENTS, PAGE Introduction ix CHAPTER I. -

The Translation of German Pietist Imagery Into Anglo-American Cultures

Copyright by Ingrid Goggan Lelos 2009 The Dissertation Committee for Ingrid Goggan Lelos Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Spirit in the Flesh: The Translation of German Pietist Imagery into Anglo-American Cultures Committee: Katherine Arens, Supervisor Julie Sievers, Co-Supervisor Sandy Straubhaar Janet Swaffar Marjorie Woods The Spirit in the Flesh: The Translation of German Pietist Imagery into Anglo-American Cultures by Ingrid Goggan Lelos, B.A.; M.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2009 Dedication for my parents, who inspired intellectual curiosity, for my husband, who nurtured my curiositities, and for my children, who daily renew my curiosities Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to so many who made this project possible. First, I must thank Katie Arens, who always believed in me and faithfully guided me through this journey across centuries and great geographic expanses. It is truly rare to find a dissertation advisor with the expertise and interest to direct a project that begins in medieval Europe and ends in antebellum America. Without her belief in the study of hymns as literature and the convergence of religious and secular discourses this project and its contributions to scholarship would have remained but vague, unarticulated musings. Without Julie Sievers, this project would not have its sharpness of focus or foreground so clearly its scholarly merits, which she so graciously identified. -

The Formula of Concord As a Model for Discourse in the Church

21st Conference of the International Lutheran Council Berlin, Germany August 27 – September 2, 2005 The Formula of Concord as a Model for Discourse in the Church Robert Kolb The appellation „Formula of Concord“ has designated the last of the symbolic or confessional writings of the Lutheran church almost from the time of its composition. This document was indeed a formulation aimed at bringing harmony to strife-ridden churches in the search for a proper expression of the faith that Luther had proclaimed and his colleagues and followers had confessed as a liberating message for both church and society fifty years earlier. This document is a formula, a written document that gives not even the slightest hint that it should be conveyed to human ears instead of human eyes. The Augsburg Confession had been written to be read: to the emperor, to the estates of the German nation, to the waiting crowds outside the hall of the diet in Augsburg. The Apology of the Augsburg Confession, it is quite clear from recent research,1 followed the oral form of judicial argument as Melanchthon presented his case for the Lutheran confession to a mythically yet neutral emperor; the Apology was created at the yet not carefully defined border between oral and written cultures. The Large Catechism reads like the sermons from which it was composed, and the Small Catechism reminds every reader that it was written to be recited and repeated aloud. The Formula of Concord as a „Binding Summary“ of Christian Teaching In contrast, the „Formula of Concord“ is written for readers, a carefully- crafted formulation for the theologians and educated lay people of German Lutheran churches to ponder and study. -

INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI film s the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough* substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproductioiL In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these wül be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. UMI University Microfilms International A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Order Nnsaber 9816176 ‘‘Ordo et lîbertas”: Church discipline and the makers of church order in sixteenth century North Germany Jaynes, JefiErey Philip, Ph.D. -

Philip Melanchthon's Influence on the English Theological

PHILIP MELANCHTHON’S INFLUENCE ON ENGLISH THEOLOGICAL THOUGHT DURING THE EARLY ENGLISH REFORMATION By Anja-Leena Laitakari-Pyykkö A dissertation submitted In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Theology University of Helsinki Faculty of Theology August 2013 Copyright © 2013 by Anja-Leena Laitakari-Pyykkö To the memory of my beloved husband, Tauno Pyykkö ii Abstract Philip Melanchthon’s Influence on English Theological Thought during the Early English Reformation By Anja-Leena Laitakari-Pyykkö This study addresses the theological contribution to the English Reformation of Martin Luther’s friend and associate, Philip Melanchthon. The research conveys Melanchthon’s mediating influence in disputes between Reformation churches, in particular between the German churches and King Henry VIII from 1534 to 1539. The political background to those events is presented in detail, so that Melanchthon’s place in this history can be better understood. This is not a study of Melanchthon’s overall theology. In this work, I have shown how the Saxons and the conservative and reform-minded English considered matters of conscience and adiaphora. I explore the German and English unification discussions throughout the negotiations delineated in this dissertation, and what they respectively believed about the Church’s authority over these matters during a tumultuous time in European history. The main focus of this work is adiaphora, or those human traditions and rites that are not necessary to salvation, as noted in Melanchthon’s Confessio Augustana of 1530, which was translated into English during the Anglo-Lutheran negotiations in 1536. Melanchthon concluded that only rituals divided the Roman Church and the Protestants. -

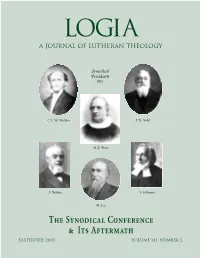

Logia 4/03 Text W/O

Logia a journal of lutheran theology Synodical Presidents C. F. W. Walther J. H. Sieker H. A. Preus J. Bading F. Erdmann M. Loy T S C I A eastertide 2003 volume xii, number 2 ei[ ti" lalei', wJ" lovgia Qeou' logia is a journal of Lutheran theology. As such it publishes articles on exegetical, historical, systematic, and liturgical theolo- T C A this issue shows the presidents of gy that promote the orthodox theology of the Evangelical the synods that formed the Evangelical Lutheran Lutheran Church. We cling to God’s divinely instituted marks of Synodical Conference (formed July at the church: the gospel, preached purely in all its articles, and the Milwaukee, Wisconsin). They include the sacraments, administered according to Christ’s institution. This Revs. C. F. W. Walther (Missouri), H. A. Preus name expresses what this journal wants to be. In Greek, LOGIA (Norwegian), J. H. Sieker (Minnesota), J. Bading functions either as an adjective meaning “eloquent,”“learned,” or (Wisconsin), M. Loy (Ohio), F. Erdmann (Illinois). “cultured,” or as a plural noun meaning “divine revelations,” “words,”or “messages.”The word is found in Peter :, Acts :, Pictures are from the collection of Concordia oJmologiva and Romans :. Its compound forms include (confes- Historical Institute, Rev. Mark A. Loest, assistant ajpologiva ajvnalogiva sion), (defense), and (right relationship). director. Each of these concepts and all of them together express the pur- pose and method of this journal. LOGIA considers itself a free con- ference in print and is committed to providing an independent L is indexed in the ATLA Religion Database, published by the theological forum normed by the prophetic and apostolic American Theological Library Association, Scriptures and the Lutheran Confessions. -

Lutheran Synod Quarterly

LUTHERAN SYNOD QUARTERLY VOLUME 52 • NUMBERS 2-3 JUNE–SEPTEMBER 2012 The theological journal of Bethany Lutheran Theological Seminary LUTHERAN SYNOD QUARTERLY EDITOR-IN-CHIEF........................................................... Gaylin R. Schmeling BOOK REVIEW EDITOR ......................................................... Michael K. Smith LAYOUT EDITOR ................................................................. Daniel J. Hartwig PRINTER ......................................................... Books of the Way of the Lord FACULTY............. Adolph L. Harstad, Thomas A. Kuster, Dennis W. Marzolf, Gaylin R. Schmeling, Michael K. Smith, Erling T. Teigen The Lutheran Synod Quarterly (ISSN: 0360-9685) is edited by the faculty of Bethany Lutheran Theological Seminary 6 Browns Court Mankato, Minnesota 56001 The Lutheran Synod Quarterly is a continuation of the Clergy Bulletin (1941–1960). The purpose of the Lutheran Synod Quarterly, as was the purpose of the Clergy Bulletin, is to provide a testimony of the theological position of the Evangelical Contents Lutheran Synod and also to promote the academic growth of her clergy roster by providing scholarly articles, rooted in the inerrancy of the Holy Scriptures and the LSQ Vol. 52, Nos. 2–3 (June–September 2012) Confessions of the Evangelical Lutheran Church. ARTICLES AND SERMONS The Lutheran Synod Quarterly is published in March and December with a “God Has Gone Up With a Shout” - An Exegetical Study of combined June and September issue. Subscription rates are $25.00 U.S. per year -

The Church As Koinonia of Salvation: Its Structures and Ministries

THE CHURCH AS KOINONIA OF SALVATION: ITS STRUCTURES AND MINISTRIES Common Statement of the Tenth Round of the U.S. Lutheran-Roman Catholic Dialogue THE CHURCH AS KOINONIA OF SALVATION: ITS STRUCTURES AND MINISTRIES Page ii Preface It is a joy to celebrate the fifth anniversary of the Joint Declaration on the Doctrine of Justification (JDDJ), signed by representatives of the Catholic Church and the churches of the Lutheran World Federation in 1999. Pope John Paul II and the leaders of the Lutheran World Federation recognize this agreement as a milestone and model on the road toward visible unity among Christians. It is therefore with great joy that we present to the leadership and members of our churches this text, the tenth produced by our United States dialogue, as a further contribution to this careful and gradual process of reconciliation. We hope that it will serve to enhance our communion and deepen our mutual understanding. Catholics and Lutherans are able to “confess: By grace alone, in faith in Christ’s saving work and not because of any merit on our part, we are accepted by God and receive the Holy Spirit, who renews our hearts while equipping and calling us to good works” (JDDJ §15). We also recognize together that: “Our consensus in basic truths of the doctrine of justification must come to influence the life and teachings of our churches. Here it must prove itself. In this respect, there are still questions of varying importance which need further clarification” (JDDJ §43). In this spirit we offer the following modest clarifications and proposals.