Governing Flood, Migration, and Conflict in North Bihar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter-4 Taxes on Vehicles

Chapter-3: Revenue and Land Reforms Chapter-4 Taxes on Vehicles k Audit Report (Revenue Sector) for the year ended 31 March 2017 l CHAPTER 4: TAXES ON VEHICLES 4.1 Tax administration The Transport Department levies and collects taxes on vehicles in the State, in terms of the Motor Vehicles (MV) Act, 1988, Central Motor Vehicles (CMV) Rules, 1989, Bihar Motor Vehicle Taxation (BMVT) Act, 1994 and BMVT Rules, 1994. The Department is headed by the Principal Secretary, Transport Department at the Government level and by the State Transport Commissioner (STC) at the apex level of the Department. The STC is assisted by two Joint State Transport Commissioners at the headquarters. The State is divided into nine Regional Transport Authorities1 (RTAs) and 38 District Transport Offices. They are assisted by Motor Vehicle Inspectors (MVIs). The main function of the RTAs is to issue road permits to the vehicles and the responsibility of registration of motor vehicles, levy and collection of fees and taxes and grant of driving licences are assigned to the District Transport Officers (DTOs) in the State. 4.2 Results of audit During 2016-17, the Accountant General test checked records of 342 out of 49 units of the Transport Department. Revenue collected by the Department during 2015-16 was ` 1,181.22 crore of which, the audited units collected ` 888.87 crore. Audit scrutiny revealed non/short levy of taxes, leviable taxes not realised from transport vehicles, and other irregularities involving ` 147.10 crore in 362 cases as shown in Table - 4.1. Table - 4.1 (` in crore) Sl. -

Ground Water Year Book, Bihar (2015 - 2016)

का셍ााल셍 उप셍ोग हेतू For Official Use GOVT. OF INDIA जल ल MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD जल ,, (2015-2016) GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK, BIHAR (2015 - 2016) म鵍य पूर्वी क्षेत्र, पटना सितंबर 2016 MID-EASTERN REGION, PATNA September 2016 ` GOVT. OF INDIA जल ल MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES जल CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD ,, (2015-2016) GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK, BIHAR (2015 - 2016) म鵍य पर्वू ी क्षेत्र, पटना MID-EASTERN REGION, PATNA सितंबर 2016 September 2016 GROUND WATER YEAR BOOK, BIHAR (2015 - 2016) CONTENTS CONTENTS Page No. List of Tables i List of Figures ii List of Annexures ii List of Contributors iii Abstract iv 1. INTRODUCTION.............................................................................................................1 2. HYDROGEOLOGY..........................................................................................................1 3. GROUND WATER SCENARIO......................................................................................4 3.1 DEPTH TO WATER LEVEL........................................................................................8 3.1.1 MAY 2015.....................................................................................................................8 3.1.2 AUGUST 2015..............................................................................................................10 3.1.3 NOVEMBER 2015........................................................................................................12 3.1.4 JANUARY 2016...........................................................................................................14 -

Bihar Military Police (BMP

FORM 1 (I) Basic Information Sl.No. Item Details 1. Name of the project/s-Bihar Military Police (B.M.P- Bihar Govt. Project 12)Supaul 2. S.No. in the schedule 3. Proposed capacity /area/length/tonnage to be Plot area=283382 sq.m handled/command area/lease area/number of wells to be TotalBuilt up drilled. area=31190.65sq.m 4. New/Expansion/Modernization NEW 5. Existing Capacity/Area etc. NIL 6. Category of Project i.e. ‘A’ or ‘B’ B 7. Does it attract the general condition? If yes, please specify. NO 8. Does it attract the specific condition? If yes, please specify. YES 9. Location - Supaul Thana no.-1 Plot/Survey/Khasra No. Khata no.-339 Village - Birpur Kesra no.-1020 Tehsil- BASHAANTPUR District SUPAUL,MAUJA-BHIMNAGAR State - BIHAR 10. Nearest railway station/airport along with distance in kms. 32kmRadhupur ( railway station) 11. Nearest Town, city, district Headquarters along with 62 km. Supaul Head Quarter distance in kms. 12. Village Panchayats, Zilla Parishad, Municipal Corporation, Birpur,Bhimnagar. Local body (complete postal addresses with telephone nos. supaul to be given) 13. Name of the applicant Dhananjay kumar (Senior Architect) 14. Registered Address Kautaliya nagar patna -14 15. Address for correspondence: Bihar police Building Name cconstruction corporation Designation (Owner/Partner /CEO) Sunil kumar. Pin code ADG CUM CMD E-mail 800014 Telephone No. [email protected] Fax No. 0612-2224529 0612-2224529 16. Details of Alternative Sites examined, if any. Location of Village-District-State these sites should be shown on a topo sheet. 1 NIL 2 3 17. -

District Plan 2011 - 12

I DISTRICT PLAN 2011 - 12 SUPAUL - i I Submitted by : District Planning Committee, Supaul Submitted to: Department of Planning & Development, Government of Bihar DISTRICT PLAN 2011 - 12 SUPAUL ¥ V *k g f II A © H f: © f&T SJkH*»»* Submitted by : District Planning Committee, Supaul Submitted to: Department of Planning & Development, Government of Bihar ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS For sustainable and planned economic development it is essential to formulate the Annual District Plan on the basis of available resources. As per the direction of the Department of Planning and Development, Government of Bihar, with an objective to prepare the effective Plan, we have collected relevant information and data ensuring the assimilation of district level important components from various departments as well as the priority sectors like Health, Education, Livelihood and Infrastructure etc. Keeping in view the past experience of formulation and implementation of various sectoral Action Annual Plans and recent directions of the department the Annual District Plan 2011 -12 for Rs. 103142.3 89 lakh has been prepared for the maximum utilization of available resources, so that the socio-economic development of the district can be further accelerated. I would like to thank Mr. Kunwar Jung Bahadur, Deputy Development Commissioner, Mr. D.N. Mishra, Regional Planning officer, Kosi Division, Mr. Prakash Yadav, District Planning Officer, Mr. Vivek Sharan (Ex. District Facihtator) and Mr. D P Karn, District Facihtator, GoI-UN Joint Convergence Program for their important contribution in formulation of Annual District Plan 2011 -12 for the district of Supaul. Mr. Brajesh Kumar Vikal, DPRO also deserves special thanks for his support in the Plan formulation. -

List of Forest Divisions with Code

Forest Account Name of Divisions in English & Hindi with Codes Sl. Divn No. Code Name of Divisions ize.Myksa dk uke 1 SMRFOR522 Sitamarhi Forest Division, Sitamarhi lhrke<h ou izze.My ] lhrke<h 2 ARRFOR504 Araria Forest Division, Araria vjfj;k ou ize.My] vjfj;k Office of the DFO-cum- 3 WCHFOR148 dk;kZy; ou ize.My inkf/kdkjh & lg& mi funs'kd Dy.Director,V.T.P.-2, Valmikinagar, okfYefd O;k?kz vkj{k]ize.My&2 okfYefd West Champaran uxj]if'pe pEikj.k 4 SRNFOR518 Saran Forest Division, Chapra lkj.k ou ize.My]Nijk 5 NWDFOR103 Nawada Forest Division, Nawada uoknk ou ize.My]uoknk 6 PRNFOR044 Purnea Forest Division, Purnea iwf.kZ;kWa ou izze.My ]iwf.kZ;kWa 7 PTNFOR040 Patna Forest Division, Patna iVuk ou izze.My ]iVuk 8 RTSFOR071 Rohtas Forest Division, Sasaram jksgrkl ou izze.My ] jksgrkl Office of the Pr. Chief Conservator of 9 PTSFOR501 Forests, Bihar, Patna dk;kZy;]iz/kku eq[; ou laj{kd]fcgkj]iVuk Office of the Regional Chief 10 BGPFOR513 Conservator of Forests, Bhagalpur dk;kZy; {kssf=; eq[; ou laj{kd]Hkkxyiqj Office of the Regional Chief 11 PTNFOR038 Conservator of Forests, Patna dk;kZy; {kssf=; eq[; ou laj{kd] iVuk Office of the Regional Chief 12 MUZFOR037 Conservator of Forests, Muzaffarpur dk;kZy; {ksf=; eq[; ou laj{kd]etq Q~Qjiqj Office of theWorking Plan Officer, dk;kZy; dk;Zokgd ;kstuk vf/kdkjh]ou dk; Z ;kstuk 13 PTNFOR041 Forest Working Plan Division, Patna izHkkx]iVuk 14 SPLFOR526 Supaul Forest Division, Supaul lqikSy ou ize.My]lqikSy 15 WCHFOR523 Bettiah Forest Division, Bettiah csfr;k ou izze.My ] csfr;k 16 PTSFOR530 Patna Park -

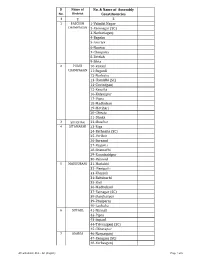

AC with District Dist

Sl Name of No. & Name of Assembly No. District Constituencies 1 2 3 1 PASCHIM 1-Valmiki Nagar CHAMPARAN 2-Ramnagar (SC) 3-Narkatiaganj 4-Bagaha 5-Lauriya 6-Nautan 7-Chanpatia 8-Bettiah 9-Sikta 2 PURVI 10-Raxaul CHAMPARAN 11-Sugauli 12-Narkatia 13-Harsidhi (SC) 14-Govindganj 15-Kesaria 16-Kalyanpur 17-Pipra 18-Madhuban 19-Motihari 20-Chiraia 21-Dhaka 3 SHEOHAR 22-Sheohar 4 SITAMARHI 23-Riga 24-Bathnaha (SC) 25-Parihar 26-Sursand 27-Bajpatti 28-Sitamarhi 29-Runnisaidpur 30-Belsand 5 MADHUBANI 31-Harlakhi 32- Benipatti 33-Khajauli 34-Babubarhi 35-Bisfi 36-Madhubani 37-Rajnagar (SC) 38-Jhanjharpur 39-Phulparas 40-Laukaha 6 SUPAUL 41-Nirmali 42-Pipra 43-Supaul 44-Triveniganj (SC) 45-Chhatapur 7 ARARIA 46-Narpatganj 47-Raniganj (SC) 48-Forbesganj AC with district Dist. - AC (English) Page 1 of 6 Sl Name of No. & Name of Assembly No. District Constituencies 1 2 3 49-Araria 50-Jokihat 51-Sikti 8 KISHANGANJ 52-Bahadurganj 53-Thakurganj 54-Kishanganj 55-Kochadhaman 9 PURNIA 56-Amour 57-Baisi 58-Kasba 59-Banmankhi (SC) 60-Rupauli 61-Dhamdaha 62-Purnia 10 KATIHAR 63-Katihar 64-Kadwa 65-Balrampur 66-Pranpur 67-Manihari (ST) 68-Barari 69-Korha (SC) 11 MADHEPURA 70-Alamnagar 71-Bihariganj 72-Singheshwar (SC) 73-Madhepura 12 SAHARSA 74-Sonbarsha (SC) 75-Saharsa 76-Simri Bakhtiarpur 77-Mahishi 13 DARBHANGA 78-Kusheshwar Asthan (SC) 79-Gaura Bauram 80-Benipur 81-Alinagar 82-Darbhanga Rural 83-Darbhanga 84-Hayaghat 85-Bahadurpur 86-Keoti 87-Jale 14 MUZAFFARPUR 88-Gaighat 89-Aurai 90-Minapur 91-Bochaha (SC) 92-Sakra (SC) 93-Kurhani 94-Muzaffarpur 95-Kanti 96-Baruraj AC with district Dist. -

Environmental Impact Assessment (Draft)

Environmental Impact Assessment (Draft) February 2016 IND: Bihar New Ganga Bridge Project Prepared by Bihar State Road Development Corporation Limited, Government of Bihar for the Asian Development Bank. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (as of 29 February 2016) Currency unit – Indian rupees (INR/Rs) Rs1.00 = $ 0.01454 $1.00 = Rs 68.7525 ABBREVIATIONS AADT - Annual Average Daily Traffic AAQ - Ambient air quality AAQM - Ambient air quality monitoring ADB - Asian Development Bank AH - Asian Highway ASI - Archaeological Survey of India BDL - Below detectable limit BGL - Below ground level BOD - Biochemical oxygen demand BSRDCL - Bihar State Road Development Corporation Limited BOQ - Bill of quantity CCE - Chief Controller of Explosives CGWA - Central Ground Water Authority CITES - Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species CO - Carbon monoxide COD - Chemical oxygen demand CPCB - Central Pollution Control Board CSC - Construction Supervision Consultant DFO - Divisional Forest Officer DG - Diesel generating set DO - Dissolved oxygen DPR - Detailed project report E&S - Environment and social EA - Executing agency EAC - Expert Appraisal Committee EFP - Environmental Focal Person EHS - Environment Health and Safety EIA - Environmental impact assessment EMOP - Environmental monitoring plan EMP - Environmental management plan ESCAP - United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and Pacific GHG - Greenhouse gas GIS - Geographical information system GOI - Government of India GRC - Grievance redress committee GRM - Grievance redress mechanism -

Deo List Bihar

Details of DEO-cum-DM Sl. No. District Name Name Designation E-mail Address Mobile No. 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 PASCHIM CHAMPARAN Kundan Kumar District Election Officer [email protected] 9473191294 2 PURVI CHAMPARAN Shirsat Kapil Ashok District Election Officer [email protected] 9473191301 3 SHEOHAR Avaneesh Kumar Singh District Election Officer [email protected] 9473191468 4 SITAMARHI Abhilasha Kumari Sharma District Election Officer [email protected] 9473191288 5 MADHUBANI Nilesh Ramchandra Deore District Election Officer [email protected] 9473191324 6 SUPAUL Sri Mahendra KUMAR District Election Officer [email protected] 9473191345 7 ARARIA Prashant Kumar District Election Officer [email protected] 9431228200 8 KISHANGANJ Aditya Prakash District Election Officer [email protected] 9473191371 9 PURNIA Rahul Kumar District Election Officer [email protected] 9473191358 10 KATIHAR Kanwal Tanuj District Election Officer [email protected] 9473191375 11 MADHEPURA Navdeep Shukla District Election Officer [email protected] 9473191353 12 SAHARSA Kaushal kumar District Election Officer [email protected] 9473191340 13 DARBHANGA Shri Thiyagrajan S. M. District Election Officer [email protected] 9473191317 14 MUZAFFARPUR Chandra Shekhar Singh District Election Officer [email protected] 9473191283 15 GOPALGANJ Arshad Aziz District Election Officer [email protected] 9473191278 16 SIWAN Amit Kumar Pandey District Election Officer [email protected] 9473191273 17 SARAN Subrat Kumar Sen District -

Katihar Saharsa Barauni Raxaul Darbhanga Muzaffarpur Chhapra

22A Muzaffar- Saharsa Muzaffar- Chhapra Raxaul Raxaul Yesvant- Sitamarhi Katihar Muzaffarpur/ Dar- Howrah Jaynagar Raxaul Dar- Muzaf- Raxaul Kanpur Chhapra Chhapra pur Adarsh pur Lok- Delhi Sadh- Delhi pur Anand Amritsar Gorakhpur bhanga Kath- Amritsar Delhi bhanga farpur Lok- Kath- Gorakh Delhi Anand Nagar Porbandar manya bhavana Sadh- Muzaf- vihar (T) Express Bandra(T) Ahmeda- godam Saryu Satya- New Ambala manya godam pur Express Vihar (T) Delhi Express Tilak (T) Express bhavana- farpur Lichchavi Avadh bad Bagh Yamuna graha Delhi Cantt. Tilak (T) Garib Intercity TRAIN NAME Garib Poora- Godaan Express Express Express Express Sabar- Express Express Express Bihar Harihar Jan Rath Express Rath biya Express mati Sampark Express Sadharan Express Express Express Express Kranti Express Express 14007#/ 19040/ Train Number 12211 15279 19270 11060 14015$ 14017# 15227 14005 15707 19038 19166 13019 14649 15273 12565 14523 15267 12209 15105 15115* 3A 3A 1A,2A3A 2A,3A 3A 3A 2A,3A 2A,3A 2A,3A 2A,3A 2A 2A,3A 2A,3A 3A 1A,2A,3A 3A 3A 2A,3A 2A,3A Class of accommodation SL,II SL,II SL,II SL,II SL,II SL,II,P SL,II,P SL,II SL,II,P SL,II SL,II SL,II SL,II SL,II,P SL,II II SL,II SL,II via via From Table No. 29A via 63 37A 64A 64 64A 64A via 63 64 24A Days of departure at M,Th, Th,Sa/ Tu,Th,Su/ M,W, Except originating station F Th,Su Su,M Sa M,W F W Daily Daily M,W,F,Sa Sa Daily Tu,F,S u Daily Daily M,Th Sa Tu Su Sa a 22.00 Km. -

Bodh Gaya 70-80

IPP217, v2 Social Assessment Including Social Inclusion A study in the selected districts of Bihar Public Disclosure Authorized (Phase II report) Public Disclosure Authorized Rajeshwar Mishra Public Disclosure Authorized ASIAN DEVELOPMENT RESEARCH INSTITUTE Public Disclosure Authorized PATNA OFFICE : BSIDC COLONY, OFF BORING PATLIPUTRA ROAD, PATNA - 800 013 PHONE : 2265649, 2267773, 2272745 FAX : 0612 - 2267102, E-MAIL : [email protected] RANCHI OFFICE : ROAD NO. 2, HOUSE NO. 219-C, ASHOK NAGAR, RANCHI- 834 002. TEL: 0651-2241509 1 2 PREFACE Following the completion of the first phase of the social assessment study and its sharing with the BRLP and World Bank team, on February 1, 2007 consultation at the BRLP office, we picked up the feedback and observations to be used for the second phase of study covering three more districts of Purnia, Muzaffarpur and Madhubani. Happily, the findings of the first phase of the study covering Nalanada,Gaya and Khagaria were widely appreciated and we decided to use the same approach and tools for the second phase as was used for the first phase. As per the ToR a detailed Tribal Development Project (TDP) was mandated for the district with substantial tribal population. Purnia happens to be the only district, among the three short listed districts, with substantial tribal (Santhal) population. Accordingly, we undertook and completed a TDP and shared the same with BRLP and the World Bank expert Ms.Vara Lakshnmi. The TDP was minutely analyzed and discussed with Vara, Archana and the ADRI team. Subsequently, the electronic version of the TDP has been finalized and submitted to Ms.Vara Lakshmi for expediting the processing of the same. -

Flood Disaster and Its Impact on the People in Kosi Region, Bihar

© 2019 IJRAR May 2019, Volume 6, Issue 2 www.ijrar.org (E-ISSN 2348-1269, P- ISSN 2349-5138) FLOOD DISASTER AND ITS IMPACT ON THE PEOPLE IN KOSI REGION, BIHAR Dr. Sanjiv Kumar Research Fellow Univ. Deptt. of Geography, T.M.B.U., Bhagalpur Introduction The Kosi, a trans-boundary river between Nepal and India is often referred to as the “Sorrow of Bihar”. The flow of the river contains excessive silt and sand, resulting in changing the courses of the river. During the past, the river has kept on changing its courses between Purnea district in the east and Darbhanga and Madhubani districts in the west. The recent disaster was created by the breach in the eastern Kosi embankment upstream of the Indian border at Kursela in the neighbouring Nepal on the 18th of August 2008. A tragedy of unparalleled dimension unleashed was over three million people living in 995 villages spreading in seven districts of Kosi region, viz. Supaul, Araria, Madhepura, Saharsa, Purnia, Khagaria and Katihar. Objectives: The purpose of the paper is to investigate the damage caused by the devastating floods due to the turbulent river Kosi recurrently and its impact on the socio-economic life of the people inhabiting in the region which is densely populated but with poor economy. The objective refers to the sustainability of an agricultural region to the occurrence of a natural disaster. The objective is to achieve in order to create a sustainable system in environmental, social and economic terms. The other objective aims to preserve or improve characteristics of the environment such as biodiversity, soil, and water and air quality. -

Patna University, Ashok Rajpath, Patna-800005 Mode of Likely Date Name of the Ph.D

Name and Address of the University : Patna University, Ashok Rajpath, Patna-800005 Mode of Likely Date Name of the Ph.D. Availing Funding Name of the Ph.D.(Full Registration Date of of Sl. No. Faculty Department Scholar with Unique Research Topic Fellowship Agency of Supervisor Time/Part Number Registration completion ID/Photo ID Yes/No Fellowship Time of Ph.D. ऩटनाका नगयीकयण एवॊ Dr. Surendra Acad/557 Social व्माऩारयक औय साॊस्कृ तिक कᴂ द्र January, 1 History Kumar, Associate Anita Kumari Full Time dt.09-06- February, 2016 No Sciences 2020 Professor 2016 के रूऩ भᴂ उत्कष ष - एक अवरोकन (16 व ॊ से 18 व ॊ सदी) ईस्टइॊडडमा कॊ ऩन के सभम बायि Dr. P.N Das, Acad/557 Social भᴂ देश शशऺा व्मवस्था: एक January, 2 History Associate Sanjiv Kumar Full Time dt.09-06- February, 2016 No Sciences 2020 Professor 2016 आरोचनात्भक अध्ममन (सन ् 1600 - 1757 ई. िक) बफहायके भहहराओॊ के उत्थान भᴂ Dr. Ranjan Sinha, Acad/557 Social January, 3 History Associate Niraj Kumar Jaiswal Full Time dt.09-06- February, 2016 खादी आॊदोरन की बूशभका No Sciences 2020 Professor 2016 (1920-1947): एक अध्ममन नक्सरवादीआॊदोरन भᴂ बफहाय के Acad/557 Social Dr. Ran Vijoy January, 4 History Ravi Shankar Kumar Full Time dt.09-06- February, 2016 भध्मभवग ष की बूशभका: बफहाय के No Sciences Kumar, Professor 2020 2016 ववशॊष सॊदब ष भᴂ Acad/557 Social Dr. Ran Vijoy बायिभᴂ भहहरा सॊगठनⴂ का उद्भव January, 5 History Shobha Verti Kumari Full Time dt.09-06- February, 2016 No Sciences Kumar, Professor 2020 2016 एवॊ ववकास - 1917 - 1947 ई.