(CPG) for the Management of Stroke Rehabilitation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of the American Mathematical Society August 2017 Volume 64, Number 7

ISSN 0002-9920 (print) ISSN 1088-9477 (online) of the American Mathematical Society August 2017 Volume 64, Number 7 The Mathematics of Gravitational Waves: A Two-Part Feature page 684 The Travel Ban: Affected Mathematicians Tell Their Stories page 678 The Global Math Project: Uplifting Mathematics for All page 712 2015–2016 Doctoral Degrees Conferred page 727 Gravitational waves are produced by black holes spiraling inward (see page 674). American Mathematical Society LEARNING ® MEDIA MATHSCINET ONLINE RESOURCES MATHEMATICS WASHINGTON, DC CONFERENCES MATHEMATICAL INCLUSION REVIEWS STUDENTS MENTORING PROFESSION GRAD PUBLISHING STUDENTS OUTREACH TOOLS EMPLOYMENT MATH VISUALIZATIONS EXCLUSION TEACHING CAREERS MATH STEM ART REVIEWS MEETINGS FUNDING WORKSHOPS BOOKS EDUCATION MATH ADVOCACY NETWORKING DIVERSITY blogs.ams.org Notices of the American Mathematical Society August 2017 FEATURED 684684 718 26 678 Gravitational Waves The Graduate Student The Travel Ban: Affected Introduction Section Mathematicians Tell Their by Christina Sormani Karen E. Smith Interview Stories How the Green Light was Given for by Laure Flapan Gravitational Wave Research by Alexander Diaz-Lopez, Allyn by C. Denson Hill and Paweł Nurowski WHAT IS...a CR Submanifold? Jackson, and Stephen Kennedy by Phillip S. Harrington and Andrew Gravitational Waves and Their Raich Mathematics by Lydia Bieri, David Garfinkle, and Nicolás Yunes This season of the Perseid meteor shower August 12 and the third sighting in June make our cover feature on the discovery of gravitational waves -

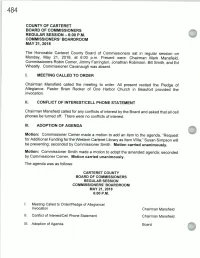

Chairman Mansfield Called for Any Conflicts of Interest by the Board and Asked That All Cell Phones Be Turned Off

COUNTY OF CARTERET BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS REGULAR SESSION — 6: 00 P. M. COMMISSIONERS' BOARDROOM MAY 21, 2018 The Honorable Carteret County Board of Commissioners sat in regular session on Monday, May 21, 2018, at 6: 00 p. m. Present were: Chairman Mark Mansfield, Commissioners Robin Comer, Jimmy Farrington, Jonathan Robinson, Bill Smith, and Ed Wheatly. Commissioner Cavanaugh was absent. I. MEETING CALLED TO ORDER Chairman Mansfield called the meeting to order. All present recited the Pledge of Allegiance. Pastor Brian Recker of One Harbor Church in Beaufort provided the invocation. II. CONFLICT OF INTEREST/CELL PHONE STATEMENT Chairman Mansfield called for any conflicts of interest by the Board and asked that all cell phones be turned off. There were no conflicts of interest. III. ADOPTION OF AGENDA Motion: Commissioner Comer made a motion to add an item to the agenda, " Request for Additional Funding for the Western Carteret Library as Item Villa-,"Susan Simpson will be presenting; seconded by Commissioner Smith. Motion carried unanimously. Motion: Commissioner Smith made a motion to adopt the amended agenda; seconded by Commissioner Comer. Motion carried unanimously. The agenda was as follows: CARTERET COUNTY BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS REGULAR SESSION COMMISSIONERS' BOARDROOM MAY 21, 2018 6: 00 P. M. Meeting Called to Order/Pledge of Allegiance/ Invocation Chairman Mansfield II. Conflict of Interest/ Cell Phone Statement Chairman Mansfield III. Adoption of Agenda Board IV. Consent Agenda Board 1. Approval of Minutes March 19, 2018 April 16, 2018 2. Tax Releases and Refunds a. Tax Releases Under $ 100 b. Tax Releases Over $ 100 C. Tax Refunds Under $ 100 d. -

The Selnolig Package: Selective Suppression of Typographic Ligatures*

The selnolig package: Selective suppression of typographic ligatures* Mico Loretan† 2015/10/26 Abstract The selnolig package suppresses typographic ligatures selectively, i.e., based on predefined search patterns. The search patterns focus on ligatures deemed inappropriate because they span morpheme boundaries. For example, the word shelfful, which is mentioned in the TEXbook as a word for which the ff ligature might be inappropriate, is automatically typeset as shelfful rather than as shelfful. For English and German language documents, the selnolig package provides extensive rules for the selective suppression of so-called “common” ligatures. These comprise the ff, fi, fl, ffi, and ffl ligatures as well as the ft and fft ligatures. Other f-ligatures, such as fb, fh, fj and fk, are suppressed globally, while making exceptions for names and words of non-English/German origin, such as Kafka and fjord. For English language documents, the package further provides ligature suppression rules for a number of so-called “discretionary” or “rare” ligatures, such as ct, st, and sp. The selnolig package requires use of the LuaLATEX format provided by a recent TEX distribution, e.g., TEXLive 2013 and MiKTEX 2.9. Contents 1 Introduction ........................................... 1 2 I’m in a hurry! How do I start using this package? . 3 2.1 How do I load the selnolig package? . 3 2.2 Any hints on how to get started with LuaLATEX?...................... 4 2.3 Anything else I need to do or know? . 5 3 The selnolig package’s approach to breaking up ligatures . 6 3.1 Free, derivational, and inflectional morphemes . -

![(B) Dz[F(Z)+G(Z)]=Dzf(Z)+Dzg(Z), (C) Dz\F(Z)G(Z) ] = [Dzf(Z)}G(Z) +F(Z)Dzg(Z). II](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1250/b-dz-f-z-g-z-dzf-z-dzg-z-c-dz-f-z-g-z-dzf-z-g-z-f-z-dzg-z-ii-701250.webp)

(B) Dz[F(Z)+G(Z)]=Dzf(Z)+Dzg(Z), (C) Dz\F(Z)G(Z) ] = [Dzf(Z)}G(Z) +F(Z)Dzg(Z). II

EXTENSION OF THE DERIVATIVE CONCEPT FOR FUNCTIONS OF MATRICES R. F. RINEHART 1. Introduction. Let Mr and Mq denote the set of all square matri- ces of order n over the real and complex fields, respectively. By a function f(Z) of a matrix Z of Mr (or M(j) is meant a mapping of a subset of Mr(Mc) into Mr(Mc). The question with which this paper is concerned is the establishment of suitable concepts of differentiabil- ity and derivative for such functions. A meaningful and useful definition of these concepts, should of course bear some noticeable resemblance to the analogous concepts for scalar functions. In addition the derivative should preserve some of the elementary properties of the derivative for scalar functions. A modest set of such desirable properties is: I (a) lif(Z) is a constant, then Dzf(Z) =0, (b) Dz[f(Z)+g(Z)]=Dzf(Z)+Dzg(Z), (c) Dz\f(Z)g(Z)] = [Dzf(Z)}g(Z)+f(Z)Dzg(Z). An additional important desired attribute, perhaps more strin- gent, is II The definitions of differentiability and derivative shall be applicable and meaningful when applied to the special functions on Mq arising from scalar functions of a complex variable [2]. For example, it would be desirable that the function ez turn out to be differentiable, accord- ing to the general definition of differentiability of functions on Mq. In the fairly extensive literature on functions defined on Mr or Mc, or more generally on linear algebras with unit element over R or C, no definition of derivative has been given which satisfactorily fulfills requirements I and II. -

Np 053 56.Pdf

LIBR RY 0 IVERSITY OF DELAWARE Since 19 ...... FEB 21 1964 Newark's For N ws of Home Town POST E~WARE People YOU Know Newspaper T N Heat I ' OL. 53, 0. 56 /)et e looers ReJJly To Cr i tic~ 1 :~ - Yc :w-Oitl Saves Conn -dot·s l)f "tlill CrPek Hon:inp: 1" I..ifc Of~ oma n I(Jil In h-m·t Attack llnu>;e-'I'o- llouRl' Call~ Planned Thi" Sund;l\ in l, arJ, , Throu!rJtnuf • '.tfion For Con!rihutiou.._ Tu \ id I' · •·trch ]n Fi 1~ ht \gain..,f l\u. 1 Health Em•my-lll•arf l>i l'' • Two .,, Creek Hundred News .1\¥0 TC\V<:u·k 1cu morning \\ith :\Irs. Robe!•l Hnll. ''We mu<t lot>k beyond hund!,tl 1 MI 1 ~ ll ml>L'rs o! thi. church nn• rl'· Lu'h,•l !:"a is. D<•lnwan• g•··m L'l'' I~----- ltr.::::I!J>~=::. • 1 knu\\' thl') l\Ul ;.:row that nmuunt 'ar Fenntngton Evaru~, Correspondent 1l•'Jv To OJ · inawa ~V,\'; 1 ,',~·<1 t~;,,~ri:~,.' ~;;~::~;~s ~~ '~~;~~ ,r th"· fullow c·u·ta•n "l'll pro"n Rohl. T. ,lotH"' Phon!' C:E 9-7798 J ' .4 , }i' , , , • . , S.n·1or i'l Wilmington on • Inr~h 6-7. , 1 racltc<' nntl l!•'t l'nough molstu•·e." I hi l'11te A •datirm E·1rh \f'tk U c ·o will b<' n ~:uct ll i 1.llllY .., X(JCJS .Jr. ChtrlLo H. Wuodwni'd rf I 1 1 •or Future I lit'' HI tht•y 11111<1 bL•!!IIl !Junkin• and ... -

Proposal for Generation Panel for Latin Script Label Generation Ruleset for the Root Zone

Generation Panel for Latin Script Label Generation Ruleset for the Root Zone Proposal for Generation Panel for Latin Script Label Generation Ruleset for the Root Zone Table of Contents 1. General Information 2 1.1 Use of Latin Script characters in domain names 3 1.2 Target Script for the Proposed Generation Panel 4 1.2.1 Diacritics 5 1.3 Countries with significant user communities using Latin script 6 2. Proposed Initial Composition of the Panel and Relationship with Past Work or Working Groups 7 3. Work Plan 13 3.1 Suggested Timeline with Significant Milestones 13 3.2 Sources for funding travel and logistics 16 3.3 Need for ICANN provided advisors 17 4. References 17 1 Generation Panel for Latin Script Label Generation Ruleset for the Root Zone 1. General Information The Latin script1 or Roman script is a major writing system of the world today, and the most widely used in terms of number of languages and number of speakers, with circa 70% of the world’s readers and writers making use of this script2 (Wikipedia). Historically, it is derived from the Greek alphabet, as is the Cyrillic script. The Greek alphabet is in turn derived from the Phoenician alphabet which dates to the mid-11th century BC and is itself based on older scripts. This explains why Latin, Cyrillic and Greek share some letters, which may become relevant to the ruleset in the form of cross-script variants. The Latin alphabet itself originated in Italy in the 7th Century BC. The original alphabet contained 21 upper case only letters: A, B, C, D, E, F, Z, H, I, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, V and X. -

JA G U a R JO U R N

A message from the principal Welcome to Guion Creek Middle School—home of the Jaguars! The school year is moving fast but there is still time to please consider joining our PTO and provide us some feedback on how we can continue to grow. Contact Ms. Burns; [email protected] Our new revamped version of STAR is up and running. We are always looking for volunteers to assist. Please contact us at 317-293-4549 Finally, don’t forget to follow us on Twitter @guioncreekms GCMS Proud, Gregory Nunley Jr. November Events Nov 1-10. High Ability Testing Nov 1. 6th & 8th Honors Recognition (GCMS Cafeteria) During School! Nov 1. Triple Threat Night 6pm-7:30pm Nov 2. 7th Grade Honors Recognition (GCMS Cafeteria) During School! Nov 3. STAR Nov 7. 21st Century Scholars Night Nov 9. Veterans Day Ceremony 3pm; Progress Reports Nov 10. STAR Upcoming Dates Nov 12-13 LEAP Series Nov. 19-23 Thanksgiving Break Triple Threat Night What: Wellness Activities Where: Guion Creek Middle School Guion creek middle school November 2018 issue Time: 6:00pm - 7:30pm Jaguar journal Guion creek Students of the Month middle Jah Kelly school Bria Harris 4401 W. 52nd Street Dametrius Latham Indianapolis, IN 46254 317-293-4549 Hermilo Martinez Fax: 317-298-2794 Sandra Contreas Attendance Line: 317-388-7996 Sandra Lopez You can access your student’s current attendance, discipline Romel Arita-Castillo and grade book information Amairani Garcia using Skyward Family Access. If Yna Petilos you need your login and/or password, please call the GCMS Andreus Pearson office at (317) 293-4549. -

1 Symbols (2286)

1 Symbols (2286) USV Symbol Macro(s) Description 0009 \textHT <control> 000A \textLF <control> 000D \textCR <control> 0022 ” \textquotedbl QUOTATION MARK 0023 # \texthash NUMBER SIGN \textnumbersign 0024 $ \textdollar DOLLAR SIGN 0025 % \textpercent PERCENT SIGN 0026 & \textampersand AMPERSAND 0027 ’ \textquotesingle APOSTROPHE 0028 ( \textparenleft LEFT PARENTHESIS 0029 ) \textparenright RIGHT PARENTHESIS 002A * \textasteriskcentered ASTERISK 002B + \textMVPlus PLUS SIGN 002C , \textMVComma COMMA 002D - \textMVMinus HYPHEN-MINUS 002E . \textMVPeriod FULL STOP 002F / \textMVDivision SOLIDUS 0030 0 \textMVZero DIGIT ZERO 0031 1 \textMVOne DIGIT ONE 0032 2 \textMVTwo DIGIT TWO 0033 3 \textMVThree DIGIT THREE 0034 4 \textMVFour DIGIT FOUR 0035 5 \textMVFive DIGIT FIVE 0036 6 \textMVSix DIGIT SIX 0037 7 \textMVSeven DIGIT SEVEN 0038 8 \textMVEight DIGIT EIGHT 0039 9 \textMVNine DIGIT NINE 003C < \textless LESS-THAN SIGN 003D = \textequals EQUALS SIGN 003E > \textgreater GREATER-THAN SIGN 0040 @ \textMVAt COMMERCIAL AT 005C \ \textbackslash REVERSE SOLIDUS 005E ^ \textasciicircum CIRCUMFLEX ACCENT 005F _ \textunderscore LOW LINE 0060 ‘ \textasciigrave GRAVE ACCENT 0067 g \textg LATIN SMALL LETTER G 007B { \textbraceleft LEFT CURLY BRACKET 007C | \textbar VERTICAL LINE 007D } \textbraceright RIGHT CURLY BRACKET 007E ~ \textasciitilde TILDE 00A0 \nobreakspace NO-BREAK SPACE 00A1 ¡ \textexclamdown INVERTED EXCLAMATION MARK 00A2 ¢ \textcent CENT SIGN 00A3 £ \textsterling POUND SIGN 00A4 ¤ \textcurrency CURRENCY SIGN 00A5 ¥ \textyen YEN SIGN 00A6 -

Waiting-Time Tail Probabilities in Queues with Long-Tail Service-Time Distributions

- 1 - WAITING-TIME TAIL PROBABILITIES IN QUEUES WITH LONG-TAIL SERVICE-TIME DISTRIBUTIONS by Joseph Abate 900 Hammond Road Ridgewood, NJ 07450-2908, USA Gagan L. Choudhury AT&T Bell Laboratories Room 3K-603, Holmdel, NJ 07733-3030, USA Ward Whitt AT&T Bell Laboratories Room 2C-178, Murray Hill, NJ 07974-0636, USA March 3, 1993 Revision: October 11, 1993 To appear in Queueing Systems - 2 - Abstract We consider the standard GI/G/1 queue with unlimited waiting room and the ®rst-in ®rst-out service discipline. We investigate the steady-state waiting-time tail probabilities P(W > x) when the service-time distribution has a long-tail distribution, i.e., when the service-time distribution fails to have a ®nite moment generating function. We have developed algorithms for computing the waiting-time distribution by Laplace transform inversion when the Laplace transforms of the interarrival-time and service-time distributions are known. One algorithm, exploiting Pollaczek's classical contour-integral representation of the Laplace transform, does not require that either of these transforms be rational. To facilitate such calculations, we introduce a convenient two- parameter family of long-tail distributions on the positive half line with explicit Laplace transforms. This family is a Pareto mixture of exponential (PME) distributions. These PME distributions have monotone densities and Pareto-like tails, i.e., are of order x − r for r > 1. We use this family of long-tail distributions to investigate the quality of approximations based on asymptotics for P(W > x) as x → ∞. We show that the asymptotic approximations with these long-tail service-time distributions can be remarkably inaccurate for typical x values of interest. -

City of Goodyear Standard Detail G-3300 G-3300 Dry Utility to Wet Utility Minimum Separation Requirements

CITY OF GOODYEAR DRY UTILITY TO WET UTILITY MINIMUM SEPARATION REQUIREMENTS G-3300 G-3300 STANDARD DETAIL CITY OF GOODYEAR VERTICAL REALIGNMENT OF WATER & RECLAIMED WATER MAINS G-3301 STANDARD DETAIL G-3301 CITY OF GOODYEAR ELECTRONIC BALL MARKER PLACEMENT G-3305 G-3305 STANDARD DETAIL CITY OF GOODYEAR BUTTERFLY VALVE OPERATOR MANHOLE G-3307 G-3307 STANDARD DETAIL CITY OF GOODYEAR WATER SERVICE CONNECTIONS G-3310 G-3310 STANDARD DETAIL CITY OF GOODYEAR 4" & 6" WATER METER VAULTS G-3313-1 G-3313-1 STANDARD DETAIL CITY OF GOODYEAR 8" WATER METER VAULT G-3313-2 STANDARD DETAIL G-3313-2 CITY OF GOODYEAR 4", 6", & 8" WATER METERS G-3313-3 G-3313-3 STANDARD DETAIL CHLORINE INJECTION ASSEMBLY TAP FOR FUTURE CHLORINE INJECTION ASSEMBLY CITY OF GOODYEAR CHLORINE INJECTIONS ASSEMBLY FOR UNDERGROUND WATERLINES G-3316 G-3316 STANDARD DETAIL CITY OF GOODYEAR DEBRIS CAP INSTALLATION G-3321 G-3321 STANDARD DETAIL CITY OF GOODYEAR PRESSURE REDUCING VALVE G-3323 G-3323 STANDARD DETAIL CITY OF GOODYEAR PRESSURE REDUCING VALVE VAULT G-3324-1 G-3324-1 STANDARD DETAIL CITY OF GOODYEAR PROPOSED PRV VAULT LID DETAIL G-3324-2 G-3324-2 STANDARD DETAIL CITY OF GOODYEAR RECLAIMED WATER VALVE BOX AND LID G-3325 G-3325 STANDARD DETAIL CITY OF GOODYEAR 2" AIR/VACUUM RELEASE VALVE G-3328 G-3328 STANDARD DETAIL CITY OF GOODYEAR FIRE HYDRANT INSTALLATION G-3330 G-3330 STANDARD DETAIL CITY OF GOODYEAR HYDRANT SAFETY POSTS G-3332 STANDARD DETAIL G-3332 CITY OF GOODYEAR TEMPORARY WATER SUPPLY HYDRANT METER ASSEMBLY G-3334 STANDARD DETAIL G-3334 CITY OF GOODYEAR FIRE HYDRANT -

Fonts for Latin Paleography

FONTS FOR LATIN PALEOGRAPHY Capitalis elegans, capitalis rustica, uncialis, semiuncialis, antiqua cursiva romana, merovingia, insularis majuscula, insularis minuscula, visigothica, beneventana, carolina minuscula, gothica rotunda, gothica textura prescissa, gothica textura quadrata, gothica cursiva, gothica bastarda, humanistica. User's manual 5th edition 2 January 2017 Juan-José Marcos [email protected] Professor of Classics. Plasencia. (Cáceres). Spain. Designer of fonts for ancient scripts and linguistics ALPHABETUM Unicode font http://guindo.pntic.mec.es/jmag0042/alphabet.html PALEOGRAPHIC fonts http://guindo.pntic.mec.es/jmag0042/palefont.html TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER Page Table of contents 2 Introduction 3 Epigraphy and Paleography 3 The Roman majuscule book-hand 4 Square Capitals ( capitalis elegans ) 5 Rustic Capitals ( capitalis rustica ) 8 Uncial script ( uncialis ) 10 Old Roman cursive ( antiqua cursiva romana ) 13 New Roman cursive ( nova cursiva romana ) 16 Half-uncial or Semi-uncial (semiuncialis ) 19 Post-Roman scripts or national hands 22 Germanic script ( scriptura germanica ) 23 Merovingian minuscule ( merovingia , luxoviensis minuscula ) 24 Visigothic minuscule ( visigothica ) 27 Lombardic and Beneventan scripts ( beneventana ) 30 Insular scripts 33 Insular Half-uncial or Insular majuscule ( insularis majuscula ) 33 Insular minuscule or pointed hand ( insularis minuscula ) 38 Caroline minuscule ( carolingia minuscula ) 45 Gothic script ( gothica prescissa , quadrata , rotunda , cursiva , bastarda ) 51 Humanist writing ( humanistica antiqua ) 77 Epilogue 80 Bibliography and resources in the internet 81 Price of the paleographic set of fonts 82 Paleographic fonts for Latin script 2 Juan-José Marcos: [email protected] INTRODUCTION The following pages will give you short descriptions and visual examples of Latin lettering which can be imitated through my package of "Paleographic fonts", closely based on historical models, and specifically designed to reproduce digitally the main Latin handwritings used from the 3 rd to the 15 th century. -

Specticle G 50Lb 80948255A 121019AV3 Etl 120312:Specticle G 50Lb 80948255A 121019AV3 Etl 120312 12/4/12 2:21 PM Page 1

Specticle G 50lb 80948255A 121019AV3 etl 120312:Specticle G 50lb 80948255A 121019AV3 etl 120312 12/4/12 2:21 PM Page 1 GROUP 29 HERBICIDE G Preemergent Herbicide for the Control of Annual Grasses, Annual Sedges, and Broadleaf Weeds in Turfgrass, Landscape Ornamentals, and Hard- scapes DO NOT USE FOR THE MANUFACTURING OF FERTILIZER ACTIVE INGREDIENT: INDAZIFLAM ..................................................................................................................0.0224% OTHER INGREDIENTS: ..........................................................................................99.9776% Total:...........................................................................................................................100.000% EPA Reg. No. 432-1523 Contains 0.0112 lbs of INDAZIFLAM in a 50 lb bag KEEP OUT OF REACH OF CHILDREN For MEDICAL and TRANSPORTATION Emergencies ONLY Call 24 Hours A Day 1-800-334-7577 For PRODUCT USE Information Call 1-800-331-2867 FIRST AID If swallowed: • Call a poison control center or doctor immediately for treatment advice. • Have person sip a glass of water if able to swallow. • Do not induce vomiting unless told to do so by a poison control center or doctor. • Do not give anything to an unconscious person. If in eyes: • Hold eyes open and rinse slowly and gently with water for 15-20 minutes. Remove contact lenses, if present, after the first 5 minutes, then continue rinsing. • Call a poison control center or doctor for treatment advice. If on skin or • Take off contaminated clothing. clothing: • Rinse skin immediately with plenty of water for 15-20 minutes. • Call a poison control center or doctor for treatment advice. If inhaled: • Move person to fresh air. • If person is not breathing, call 911 or an ambulance, then give artificial respiration, preferably mouth- to-mouth if possible. • Call a poison control center or doctor for further treatment advice.