East Face of Thor Peak

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PARK 0 1 5 Kilometers S Ri South Entrance Road Closed from Early November to Mid-May 0 1 5 Miles G Ra River S Access Sy

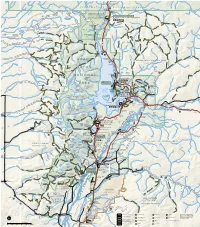

To West Thumb North Fa r ll ve YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK 0 1 5 Kilometers s Ri South Entrance Road closed from early November to mid-May 0 1 5 Miles G ra River s access sy ad Grassy Lake L nch Ro a g Ra Reservoir k lag e F - Lake of Flagg Ranch Information Station R n the Woods to o Road not recommended 1 h a Headwaters Lodge & Cabins at Flagg Ranch s d for trailers or RVs. Trailhead A Closed in winter River G r lade C e access re e v k i R SS ERNE CARIBOU-TARGHEE ILD Glade Creek e r W Trailhead k Rive ITH a Falls n 8mi SM S NATIONAL FOREST 13km H Indian Lake IA JOHN D. ROCKEF ELLER, JR. D E D E J To South Bo C Pinyon Peak Ashton one C o reek MEMORIAL PARKWAY u 9705ft lt er Creek Steamboat eek Cr Mountain 7872ft Survey Peak 9277ft 89 C a n erry re B ek o z 191 i 287 r A C o y B o a t il e eek ey r C C r l e w e O Lizard C k r k Creek e e e re k C k e e r m C ri g il ly P z z ri G Jackson Lake North Bitch Overlook Cre ek GRAND BRIDGER-TETON NATIONAL FOREST N O ANY k B C ee EB Cr TETON WILDERNESS W Moose Arizona Island Arizona 16mi Lake k e 26km e r C S ON TETON NY o A u C t TER h OL C im IDAHO r B ilg it P ch Moose Mountain rk Pacic Creek k WYOMING Fo e Pilgrim e C 10054ft Cr re e Mountain t k s 8274ft Ea c Leeks Marina ci a P MOOSE BASIN NATIONAL Park Boundary Ranger Peak 11355ft Colter Bay Village W A k T e E N e TW RF YO r O ALLS CAN C O Colter Bay CE m A ri N g Grand View Visitor Center il L PARK P A Point KE 4 7586ft Talus Lake Cygnet Two Ocean 2 Pond Eagles Rest Peak ay Lake Trailhead B Swan 11258ft er lt Lake o Rolling Thunder -

Grand Teton National Park Wyoming

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR RAY LYMAN WILBUR. SECRETARY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE HORACE M.ALBRIGHT. DIRECTOR CIRCULAR OF GENERAL INFORMATION REGARDING GRAND TETON NATIONAL PARK WYOMING © Crandall THE WAY TO ENJOY THE MOUNTAINS THE GRAND TETON IN THE BACKGROUND Season from June 20 to September 19 1931 © Crandill TRIPS BY PACK TRAIN ARE POPULAR IN THE SHADOWS OF THE MIGHTY TETONS © Crandall AN IDEAL CAMP GROUND Mount Moran in the background 'Die Grand Teton National Park is not a part of Yellowstone National Park, and, aside from distant views of the mountains, can not be seen on any Yellowstone tour. It is strongly urged, how ever, that visitors to either park take time to see the other, since they are located so near together. In order to get the " Cathedral " and " Matterhorn " views of the Grand Teton, and to appreciate the grandeur and majestic beauty of the entire Teton Range, it is necessary to spend an extra day in this area. CONTENTS rage General description 1 Geographic features: The Teton Range 2 Origin of Teton Range 2 Jackson Hole 4 A meeting ground for glaciers .. 5 Moraines 6 Outwash plains 6 Lakes 6 Canyons 7 Peaks 7 How to reach the park: By automobile . 7 By railroad 9 Administration 0 Motor camping 11 Wilderness camping • 11 Fishing 11 Wild animals 12 Hunting in the Jackson Hole 13 Ascents of the Grand Teton 13 Rules and regulations 14 Map 18 Literature: Government publications— Distributed free by the National Park Service 13 Sold by Superintendent of Documents 13 Other national parks ' 19 National monuments 19 References 19 Authorized rates for public utilities, season of 1931 23 35459°—31 1 j II CONTENTS MAPS AND ILLUSTRATIONS COVER The way to enjoy the mountains—Grand Teton in background Outside front. -

Naturalist Pocket Reference

Table of Contents Naturalist Phone Numbers 1 Park info 5 Pocket GRTE Statistics 6 Reference Timeline 8 Name Origins 10 Mountains 12 Things to Do 19 Hiking Trails 20 Historic Areas 23 Wildlife Viewing 24 Visitor Centers 27 Driving Times 28 Natural History 31 Wildlife Statistics 32 Geology 36 Grand Teton Trees & Flowers 41 National Park Bears 45 revised 12/12 AM Weather, Wind Scale, Metric 46 Phone Numbers Other Emergency Avalanche Forecast 733-2664 Bridger-Teton Nat. Forest 739-5500 Dispatch 739-3301 Caribou-Targhee NF (208) 524-7500 Out of Park 911 Grand Targhee Resort 353-2300 Jackson Chamber of Comm. 733-3316 Recorded Information Jackson Fish Hatchery 733-2510 JH Airport 733-7682 Weather 739-3611 JH Mountain Resort 733-2292 Park Road Conditions 739-3682 Information Line 733-2291 Wyoming Roads 1-888-996-7623 National Elk Refuge 733-9212 511 Post Office – Jackson 733-3650 Park Road Construction 739-3614 Post Office – Moose 733-3336 Backcountry 739-3602 Post Office – Moran 543-2527 Campgrounds 739-3603 Snow King Resort 733-5200 Climbing 739-3604 St. John’s Hospital 733-3636 Elk Reduction 739-3681 Teton Co. Sheriff 733-2331 Information Packets 739-3600 Teton Science Schools 733-4765 Wyoming Game and Fish 733-2321 YELL Visitor Info. (307) 344-7381 Wyoming Highway Patrol 733-3869 YELL Roads (307) 344-2117 WYDOT Road Report 1-888-442-9090 YELL Fill Times (307) 344-2114 YELL Visitor Services 344-2107 YELL South Gate 543-2559 1 3 2 Concessions AMK Ranch 543-2463 Campgrounds - Colter Bay, Gros Ventre, Jenny Lake 543-2811 Campgrounds - Lizard Creek, Signal Mtn. -

T E T O N R a N

To West Thumb Road closed from early November to mid-May F al er YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK ls iv R South Entrance G River ra s access sy S Camping along Grassy Lake Road ES ad Grassy Lake L ERN nch Ro a LD g Ra Reservoir k Fourteen primitive sites are free; I lag e W F first-come, first-served; and have - Lake of Flagg Ranch Information Station E R L n the Woods O o a picnic table, metal fire ring, pit H to Headwaters Lodge & Cabins at Flagg Ranch h a toilet, but no potable water. R s d Trailhead A A G E r River N I Glade C e access re e v W k i R S ERNES CARIBOU-TARGHEE ILD Glade Creek e r W Trailhead k Rive ITH a Falls M n 8mi NATIONAL FOREST S S 13km H Indian Lake IA JOHN D. ROCKEF ELLER, JR. D E D E J To C Pinyon Peak South Boo o ne Cr u 9705ft Ashton eek MEMORIAL PARKWAY lt er 2958m Road not recommended Creek for trailers or RVs. eek Steamboat Cr Closed in winter Mountain 7872ft 2399m Survey Peak 9277ft 2827m 89 a ry Cre n Ber ek o z i 191 r 287 A C C on o an B y t a o C il t ree e e k eek y r C C r l e w Lizard C e O k k r e Creek e e e r k C k e e m r ri C lg Pi ly z z ri G Jackson Lake orth Overlook N Bitch C reek GRAND BRIDGER-TETON NATIONAL FOREST S o u N th O Y k AN e B B C re TETON WILDERNESS i EB C tc W se Arizona h Moo Island Cr Arizona ee k 16mi Lake k e e 26km r C ON TETON NY CA ER OLT C im gr IDAHO il P k Moose Mountain ork Pacific Creek e F e WYOMING Pilgrim r 10054ft C Mountain 3064m t 8274ft as c E fi Leeks Marina ci 2522m a P Park Boundary MOOSE BASIN NATIONAL Ranger Peak 11355ft 3461m Colter Bay Village W A k T e T E -

A Brief History of the Trails of Grand Teton National Park 55

Pritchard: A Brief History of the Trails of Grand Teton National Park 55 A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE TRAILS OF GRAND TETON NATIONAL PARK JAMES A. PRITCHARD IOWA STATE UNIVERSITY AMES ABSTRACT reconstructed during the MISSION 66 era, but some of the stone stairs along the way from the boat dock This project investigated the history of the to Hidden Falls date back to the CCC era. backcountry trail system in Grand Teton National Park (GTNP). In cooperation with GTNP Cultural Walking on a beautiful mountain path, one Resources and the Western Center for Historic might never guess the extensive preparation of rock Preservation in GTNP, we located records describing materials (expediting drainage) that is required before the early development of the trail system. Only a few the surface ―treadway‖ is laid down (Barter et al. historical records describe or map the exact location 2006). In fact, trails are significant engineering of early trails, which prove useful when relocating achievements that need constant care and upkeep, trails today. The paper trail becomes quite rich, including annual clearance of vegetation and the however, in revealing the story behind the practical occasional repair to sections of trail. development of Grand Teton National Park as it joined the National Park Service system. Pre-existing Trails Archeological sites are present in the upper INTRODUCTION parts of Berry Creek drainage, thought to represent ―basecamps‖ occupied consistently over 8,000 years. Grand Teton National Park and its trail A notable pre-historic travel route traversed the system developed together during the early years of northern end of the Teton Range, from the west into National Park Service (NPS) administration. -

Holly Lake, Located in Paintbrush Canyon, Is Fastest Accessed from the String Lake Trailhead of Grand Tetons National Park. It

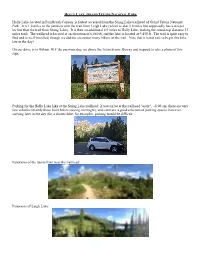

! HOLLY LAKE, GRAND TETONS NATIONAL PARK Holly Lake, located in Paintbrush Canyon, is fastest accessed from the String Lake trailhead of Grand Tetons National Park. It is 1.6 miles to the junction with the trail from Leigh Lake (which is also 1.6 miles but supposedly has a steeper incline than the trail from String Lake). It is then an additional 4.9 miles to Holly Lake, making the round-trip distance 13 miles total. The trailhead is located at an elevation of 6,880 ft, and the lake is located at 9,450 ft. The trail is quite easy to find and is well-travelled, though we did not encounter many hikers on the trail. Note that it is not safe to begin this hike !late in the day! On our drive in to Wilson, WY the previous day, we drove the Teton Scenic Byway and stopped to take a photo of this sign: ! ! Parking for the Holly Lake hike at the String Lake trailhead; if you arrive at the trailhead "early", ~8:00 am, there are very few vehicles (mainly those from hikers staying overnight), and can have a good selection of parking spaces; however, arriving later in the day (for a shorter hike, for example), parking would be difficult: ! ! Panorama of the tetons from near the trailhead: ! ! Panorama of Leigh Lake: ! ! Leigh Lake: ! ! Another panorama from the trail along the western rim of Leigh Lake: ! ! The trail leaves the rim of Leigh Lake near the northern end of the lake and ascends through some short trees: ! ! This may be a potential route to Rockchuck Peak, as we saw a hiker leave the trail near here who appeared to ascend towards the distant -

Backcountry Camping Brochure

National Park Service Grand Teton U.S. Department of the Interior Grand Teton National Park John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Memorial Parkway Backcountry Camping The North Fork of Cascade Canyon - Danielle Lehle photo Before Leaving Home Weather Planning Your Trip Group Size Boating This guide provides general information about backcountry use in Grand Teton National Individual campsites accommodate one to Register all vessels annually with the park. Park and the John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Memorial Parkway. The map on the back page is six people. Groups of seven to 12 people Purchase permits at the Craig Thomas, only for general trip planning and/or campsite selection. For detailed information, use a must use designated group sites that are Colter Bay or Jenny Lake (cash only) visitor topographic map or hiking guide. When planning your trip, consider each member of your larger and more durable. In winter, parties centers. Lakeshore campsites are located party. Backpackers should expect to travel no more than 2 miles per hour, with an additional are limited to 20 people. on Jackson and Leigh lakes. Camping is hour for every 1,000 feet of elevation gain. Do not plan to cross more than one mountain not allowed along the Snake River. Strong The table below summarizes weather at Moose, WY, 6467 feet. Temperatures in the Teton pass in a day. If you only have one vehicle, you may want to plan a loop trip. There is no Backcountry Conditions afternoon winds occur frequently. For Range can change quickly and be much colder at upper elevations. Check the local area shuttle service in the park, but transportation services are available; ask at a permits desk for Snow conditions vary annually. -

Paintbrush Divide Loop Trail

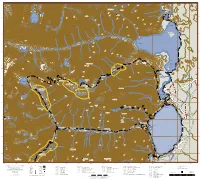

-110.860 -110.850 -110.840 -110.830 -110.820 -110.810 -110.800 -110.790 -110.780 -110.770 -110.760 -110.750 -110.740 -110.730 -110.720 -110.710 9 , 6 0 0 0 0 8 , 0 00 6 1 6 ,60 8, 1 0 1 , 2 0 0 Mount Moran 12605 T East Horn ra p 9, 00 Trapper p 2 e r Lake L a 0 k 60 e , 1 T 1 .55 r 00 West Horn ,0 1 1 0 0 Thor Peak 6 , 43.830 0 1 43.830 Cirque Lake 0 0 00 4 ,4 Bearpaw Lake , 9 .25 9 00 ,6 0 0 1 0 6 , 0 9 0 1 0 ,8 0,0 0 8 .35 7,200 0 0 8 8,200 , 8,4 7 00 00 9,2 Leigh Lake 0 0 0 , 9 8,0 00 L e ig h L a k e Mystic Island 0 T 43.820 00 r 43.820 8, a i l 7,400 1.30 0 Leigh Canyon 7,00 9,200 7, 200 0 8,00 Leigh Lake 9,4 00 8,600 Mink Lake 0 0 6 0, 43.810 43.810 1 9,600 8 ,800 00 ,8 9 0 9,00 0 0 ,4 8 0 ,40 10 7 9,6 ,400 00 Grizzly Bear Lake Hol 4.90 ly La k e 0 Mount Woodring 11590 T 0 7,600 ra Leigh Lake ,4 il 0 1 0 l 0 i 0 0 00 a 1 0 1,4 2 r , , 1 7 T 1 0 e 0 k 8,0 a Boulder Island L h 43.800 g 43.800 9,8 i 00 e L ail Tr S n ke tri g Lak La e T lly r .75 1.50 Ho 10,400 8 , 80 0 00 9,8 Outlier Site 0 9, 60 0 0 2 P , ai 1 7 .80 ntb 0,6 1.75 rus 00 h Di 10,60 8 vid 0 ,4 00 e T ra 1.30 il Holly Lake Site Holly Lake 00 9 Paintbrush Divide 0 ,4 Lake Solitude ,4 10,00 9 00 9 ,2 0 2.25 0 Paint 0 0 N bru ,0 il s 8 ra o h C T r 10 ke t ,8 a a h L 0 n 0 g F y n on Tr ri o Paintbrush Canyon a t Cathedral Group r 9 il S 43.790 k ,8 43.790 00 il Turnout o Holly Lake Group Site ra f T e C k a La s lly 1 c 9,200 Ho 0 ad ,0 e Ca p 0 ny oo 0 on Rockchuck Peak L ke North Fork of S a L tr y i n 00 n n Cascade Canyon 9,6 g e J L .55 a k e T d r Access a Ramp o -

Grand Teton National Park

To West Thumb Road closed from early November to mid-May F al r ls ve YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK Ri South Entrance ERNESS ILD Grassy Lake W E oad Reservoir L R Flagg Ranch O H r e te Information Station ak in R L w Trailhead A in y G s ed s os E ra cl Lake of the Woods N G I CARIBOU-TARGHEE W r r F ve e all i NATIONAL FOREST iv Huckleberry Mountain s R R 8mi 9615ft 13km 2930m Indian Lake JOHN D. ROCKEFELLER, JR. Pinyon Peak e k 9705ft a n 2958m S C o u MEMORIAL PARKWAY lte r No trailers or large RVs Creek on one-lane portion eek Steamboat Cr Mountain 7872ft 2399m Survey Peak 9277ft 2827m 89 a n o y err C z B r i e r e 191 k A 287 B a ek il re ey C o C ntant ek e r C C k l e w r O e re e C k Lizard k e Creek e r C m ri g ly il z P z ri G Jackson Lake N Overlook or th Bi BRIDGER-TETON NATIONAL FOREST S tch o u C re th ek N NYO k CA e B BB re it E C c W Arizona Island h Moose TETON WILDERNESS Arizona Cr ee Lake k 16mi 26km ON CANY ER OLT C Pilgrim Mountain IDAHO Moose Mountain 8274ft k 2522m ee WYOMING r 10054ft C rk 3064m o Leeks Marina F c Ranger Peak t ifi s c 11355ft E a a E P 3461m K MOOSE BASIN ek A Park Boundary re C L GRAND TETON im W r lg T A i W TER YON Colter Bay P O F N ALLS CA Colter Bay Village O C Visitor Center EA N Indian Arts Museum Grand View Point LA and Trailhead KE NATIONAL PARK 7327ft Cygnet Talus Lake 2233m Pond m y Eagles Rest Peak 4 a N B Swan 6 r 11258ft e 0 lt Lake 3431m O 2 o C LD Rolling Thunder Mountain ATI A M L S t A 10908ft North f K M Jackson Lake Lodge A E dger 3325m K 2 M Ba Cre o 7 Medical Clinic uth ek -

Grand Teton NATIONAL PARK

Grand Teton NATIONAL PARK. WYOMING Ii . .. •.. .. The lofty peaks of the Grand Tetons-blue-gray SEEING GRAND TETON pyramids of 2'12-billion-year-old rock, glacier- Grand Teton's avenues of approach are them- carved and still glacier-spotted-their canyons selves of great interest and beauty, and afford and forested lower slopes, and the basin called magnificent distant views of the Teton Range. Jackson Hole are all encompassed in Grand Teton The country traversed is rich in associations of National Park. the Old West and contains numerous historic Rising steeply 7,000 feet above the almost-level places well worth your investigation. basin of sagebrush flats and morainal lakes, this Many of the park's finest scenic offerings can be most scenic part of the Teton Range was a land- viewed only by following the trails, which pene- mark for Indians and frontiersmen. The Grand, trate into deep canyons, follow cascading streams, Middle, and South Tetons were called Les Trois and eventually lead to high alpine meadows. Tetons by trappers and explorers of the early Dozens of jewel-like lakes are discovered in un- 19th century. The Grand Teton, at 13,770 feet, is expected places. Interesting patterns of banded the dominating figure. gneiss ornament sheer cliffs. In many places, The snowfields and small glaciers that hang on canyon walls are crisscrossed with light-colored the peaks, the U-shaped canyons with cirques granites or pegmatites intruded in darker gneiss. at the heads, and the terminal moraines that rim The trails are well marked with directional signs the large lakes in the basin are reminders of the giving destinations and distances. -

Leigh N. Ortenburger Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt058031d5 No online items Guide to the Leigh N. Ortenburger Papers Irene Beardsley Department of Special Collections Green Library Stanford University Libraries Stanford, CA 94305-6004 Phone: (650) 725-1022 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc/ © 2008 The Board of Trustees of Stanford University. All rights reserved. Guide to the Leigh N. M1503 1 Ortenburger Papers Guide to the Leigh N. Ortenburger Papers Collection number: M1503 Department of Special Collections and University Archives Stanford University Libraries Stanford, California Processed by: Irene Beardsley Date Completed: 2009 Encoded by: Bill O'Hanlon © 2008 The Board of Trustees of Stanford University. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Leigh N. Ortenburger papers Dates: 1929-1996 Collection number: M1503 Creator: Leigh N. Ortenburger Collection Size: 37 linear feet53 manuscript boxes, 6 4x6 boxes, 16 flat boxes, 2 map folders Repository: Stanford University. Libraries. Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives. Abstract: The papers of Leigh N. Ortenburger contain correspondence, personal papers, maps, manuscripts, and photographic negatives and prints, with emphasis on the Cordillera Blanca in Peru and the Teton Range in Wyoming. He was the early author and eventual co-author of the definitive climber?s guide to the Teton Range, had nearly finished a manuscript on the early exploration of the range, including the controversy on the first ascent of the Grand Teton, and in ten trips to the Cordillera Blanca had obtained extensive material for a photo essay on the range which was never finished. Physical location: Special Collections materials are stored offsite and must be paged in advance. -

Neoarchean Tectonic History of the Teton Range: Record of Accretion

Research Paper THEMED ISSUE: Active Margins in Transition—Magmatism and Tectonics through Time: An Issue in Honor of Arthur W. Snoke GEOSPHERE Neoarchean tectonic history of the Teton Range: Record of accretion GEOSPHERE; v. 14, no. 3 against the present-day western margin of the Wyoming Province doi:10.1130/GES01559.1 B. Ronald Frost1, Susan M. Swapp1, Carol D. Frost1, Davin A. Bagdonas1,2, and Kevin R. Chamberlain1,3 1Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyoming 82071, USA 18 figures; 1 set of supplemental files 2Carbon Management Institute, University of Wyoming, Laramie, Wyoming 82071, USA 3Faculty of Geology and Geography, Tomsk State University, Tomsk 634050, Russia CORRESPONDENCE: [email protected] ABSTRACT INTRODUCTION CITATION: Frost, B.R., Swapp, S.M., Frost, C.D., Bag- donas, D.A., and Chamberlain, K.R., 2018, Neoar- chean tectonic history of the Teton Range: Record Although Archean gneisses of the Teton Range crop out over an The Wyoming Province is an Archean craton that occupies most of of accretion against the present-day western margin area of only 50 × 15 km, they provide an important record of the Ar- Wyoming and portions of Montana, and adjacent states. The Archean rocks of the Wyoming Province: Geosphere, v. 14, no. 3, chean history of the Wyoming Province. The northern and southern are exposed in the cores of basement-involved Laramide uplifts. The early p. 1008–1030, doi:10.1130/GES01559.1. parts of the Teton Range record different Archean histories. The north- mafic crust appears to have been Hadean (Frost et al., 2017), though most of ern Teton Range preserves evidence of 2.69–2.68 Ga high-pressure the exposed area consists of Paleoarchean to Neoarchean quartzofeldspathic Science Editor: Shanaka de Silva Guest Associate Editor: Joshua Schwartz granulite metamorphism (>12 kbar, ~900 °C) followed by tectonic as- orthogneisses that retain an isotopic signature of that ancient crust (Frost, 1993).