How to Teach Your Preschool Child to Read at Home: a Primer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celebrity Makeup Artist Mally Roncal Visited the Early Show to Show How to Get Yourself Looking Great Without Having Your Face Melt Off in the Summer Heat!

Celebrity makeup artist Mally Roncal visited The Early Show to show how to get yourself looking great without having your face melt off in the summer heat! FACE: Products: Laura Gellar Spackle Tinted Under Make-up Primer QVC.com $24.00 Cle De Peau Beaute Powder Foundation Saks Fifth Avenue Stores $75.00 Shiseido Multi Shade Enhancer Sephora.com $25.00 E.L.F Mineral Powder Foundation SPF15 eyelipsface.com $5.00 As soon as heat and humidity set in, so does sweating. And if you're wearing foundation, it can turn into a greasy, slick mess, leaving your skin looking oily, streaky, and patched with clumps of makeup. So can you get your skin looking dewy and beautiful without having the heat melt it off? The secret, says Mally, is to use primer and a powder foundation. The primer will lock moisture into your skin, and provide a smooth surface to apply foundation on; the powder foundation will cover your skin to even it out and make it look glowy without risking melting (since it's oil free) Directions: 1) Apply the primer all over an already cleansed and moisturized face and allow to sink in skin for one minute. 2) Apply a powder foundation with a brush in a circular motion buffing it into the skin. This works the best because it gives a seamless natural finish that doesn't look like makeup. It also combats shine, and it's an all-in-one foundation & powder application! EYES: Products: YSL EverlongWaterproof Mascara YSLbeautyus.com $27.50 Mally Beauty 24/7 Eye-lining System QVC.com $25.00 Many women find that after applying their eye makeup in the morning, by mid-afternoon it's run and melted down their eyes, leaving them with dark streaks and shadows well below the lash line. -

Sampling Inner Experience in the Learning Disabled Population

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-1992 Sampling inner experience in the learning disabled population Barbara Lynn Schamanek University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Schamanek, Barbara Lynn, "Sampling inner experience in the learning disabled population" (1992). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 187. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/sa8u-f0vh This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Color Theory and Cosmetics Emma E

Central Washington University ScholarWorks@CWU Undergraduate Honors Theses Student Scholarship and Creative Works Spring 2016 Color Theory and Cosmetics Emma E. Mahr Central Washington University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.cwu.edu/undergrad_hontheses Part of the Photography Commons Recommended Citation Mahr, Emma E., "Color Theory and Cosmetics" (2016). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 6. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship and Creative Works at ScholarWorks@CWU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@CWU. Color Theory and Cosmetics Emma Mahr Senior Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Graduation Arts & Humanities Honors Program William O. Douglas Honors College Central Washington University May 2016 Accepted by: ___________________________________________________________ __________ Andrea Eklund, Associate Professor, Family & Consumer Sciences Dept. Date _________________________________________________________ __________ Katherine Boswell, Lecturer, English Department Date 2 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Introduction 4 Background 5 A Brief History of Modern Cosmetics 5 Terms Defined 8 Methods 9 Models 9 Consultations 10 Products 11 Sanitation 13 Process 13 Look One 14 Look Two 14 Look Three 15 Individualized Looks 16 Analysis 17 Look One 17 Look Two 18 Look Three 19 Individualized Looks 20 Reflection 21 References 23 Appendix Consent Forms 25 Face Templates 28 Photographs 35 3 Abstract In this research project, I attempted to discover what difference does color make on the perception of the face. I examined the effects of cosmetics on the appearance of the face using color theory. Three models were used for this project. -

Rehearsal, Show, Hair & Makeup Guidelines

Rehearsal, Show, Hair & Makeup Guidelines Rehearsal & Show Guidelines to Make a JOYful Experience for All: ALWAYS – Check to be sure you have everything needed. Designate a “Show Bag” with all your items. We provided a checklist for costume pieces in the Costume Book to make it easier. We recommend making your own checklist for Hip Hop Costumes. Check these lists before coming to the show and when leaving the theater every time. – Write names on all costume pieces, tights and shoes. – Please plan ahead and be on time. – Costumes should be clean and unwrinkled. – Sewing is always preferred over pinning when making any costume fixes/adjustments. – Underwear should not be worn under tights if they are visible or show lines. If the audience can’t see them under your costume, no one needs to know. – Please do not wear any jewelry that doesn’t go with the costume. Neat nail polish as part of your hip hop style / finale costume is fine, but no nail polish in matchingcostumed classes. – Please plan meals accordingly. Pack a water bottle and small snacks. Please have a wrap or cover up available because it’s never a good idea to eat in costume. REHEARSAL – Only one parent or guardian per dancer at the Rehearsal please. – Videotaping and Flash Photography are not allowed. Nonflash photos at Rehearsal are fine! We want dancers to get to rehearse without the pressure of being videotaped. – Hair & Makeup should be done at the Dress Rehearsal. We would like to see if a dancer needs more or less of anything. -

White Paper: Dyslexia and Read Naturally 1 Table of Contents Copyright © 2020 Read Naturally, Inc

Dyslexia and Read Naturally Cory Stai Director of Research and Partnership Development Read Naturally, Inc. Published by: Read Naturally, Inc. Saint Paul, Minnesota Phone: 800.788.4085/651.452.4085 Website: www.readnaturally.com Email: [email protected] Author: Cory Stai, M.Ed. Illustration: “A Modern Vision of the Cortical Networks for Reading” from Reading in the Brain: The New Science of How We Read by Stanislas Dehaene, copyright © 2009 by Stanislas Dehaene. Used by permission of Viking Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. Copyright © 2020 Read Naturally, Inc. All rights reserved. Table of Contents Part I: What Is Dyslexia? . 3 Part II: How Do Proficient Readers Read Words? . 9 Part III: How Does Dyslexia Affect Typical Reading? . .. 15 Part IV: Dyslexia and Read Naturally Programs . 18 End Notes . 24 References . 28 Appendix A: Further Reading . 35 Appendix B: Program Scope and Sequence Summaries . 36 White Paper: Dyslexia and Read Naturally 1 Table of Contents Copyright © 2020 Read Naturally, Inc. Table of Contents 2 White Paper: Dyslexia and Read Naturally Copyright © 2020 Read Naturally, Inc. Read Naturally’s mission is to facilitate the learning necessary for every child to become a confident, proficient reader . Dyslexia is a reading disability that impacts millions of Americans . To support learners with dyslexia, educators must understand: n what dyslexia is and what it is not n how the dyslexic brain differs from that of a typical reader n how and why recommended reading interventions help To these ends, this paper supports educators to deepen their understanding of the instructional needs of dyslexic readers and to confidently select and use Read Naturally intervention programs, as appropriate . -

The Online Journal of Missouri Speech-Language-Hearing Association 2015

THE ONLINE JOURNAL OF MISSOURI SPEECH-LANGUAGE-HEARING ASSOCIATION 2015 The Online Journal of Missouri Speech- Language-Hearing Volume1; Number 1; 2015 Association © Missouri Speech-Language- Hearing Association 2015 Ray, Jayanti Annual Publication of the Missouri Speech- Language-Hearing Association Scope of OJMSHA The Online Journal of MSHA is a peer-reviewed interprofessional journal publishing articles that make clinical and research contributions to current practices in the fields of Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology. The journal is also intended to provide updates on various professional issues faced by our members while bringing them the latest and most significant findings in the field of communication disorders. The journal welcomes academicians, clinicians, graduate and undergraduate students, and other allied health professionals who are interested or engaged in research in the field of communication disorders. The interested contributors are highly encouraged to submit their manuscripts/papers to [email protected]. An inquiry regarding specific information about a submission may be emailed to Jayanti Ray ([email protected]). Upon acceptance of the manuscripts, a PDF version of the journal will be posted online. Our first issue is expected to be published in August. This publication is open to both members and nonmembers. Readers can freely access or cite the article. 2 THE ONLINE JOURNAL OF MISSOURI SPEECH-LANGUAGE-HEARING ASSOCIATION 2015 The Online Journal of Missouri Speech-Language-Hearing Association Vol. 1 No. 1 ∙ August 2015 Table of Contents Story Presentation Effects on the Narratives of Preschool Children 8 From Low and Middle Socioeconomic Homes Grace E. McConnell Evidence-Based Practice, Assessment, and Intervention Approaches for 25 Children with Developmental Dyslexia Ryan Riggs Advocacy Training: Taking Charge of Your Future 37 Nancy Montgomery, Greg Turner, and Robert deJonge Working with Your Librarian 42 Cherri G. -

Formulations: Anti-Ageing Products for Skin & Hair

Additional Information: COSSMA , issue 10/ 2015 http://www.cossma.com www.ru.cossma.com http://www.cossma.com/subscription www.cossma.com/china http://www.cossma.com/tv Formulations: Anti-Ageing Products for Skin & Hair Natural Youth Elixir http://www.cossma.com/fileadmin/all/cossma/Archiv/Formulations2015/Cos1510_Abrasca.pdf.pdf A. Brasca Silky Sun Shield Lotion (SPF 50+) http://www.cossma.com/fileadmin/all/cossma/Archiv/Formulations2015/Cos1510_Akzo.pdf.pdf AkzoNobel Age spot reduction spray for neck and décolleté http://www.cossma.com/fileadmin/all/cossma/Archiv/Formulations2015/Cos1510_Alfa.pdf Alfa Chemicals Silicone-free Moisture Softening Shampoo http://www.cossma.com/fileadmin/all/cossma/Archiv/Formulations2015/Cos1510_Ashland.pdf Ashland Magic CC Cream http://www.cossma.com/fileadmin/all/cossma/Archiv/Formulations2015/Cos1510_Azelis.pdf Azelis Maintenance – Bright Eyes Anti-wrinkle Eye Care Serum http://www.cossma.com/fileadmin/all/cossma/Archiv/Formulations2012/Cos1310_BASFBrightEyesAntiWrinkle.pdf BASF All Day Young Cream http://www.cossma.com/fileadmin/all/cossma/Archiv/Formulations2015/Cos1510_Biesterfeld.pdf Biesterfeld Spezialchemie Nutri 35/50 relaxing & anti-ageing care http://www.cossma.com/fileadmin/all/cossma/Archiv/Formulations2015/Cos1510_Erbsloe.pdf C.H. Erbslöh Anti-Ageing Night Cream http://www.cossma.com/fileadmin/all/cossma/Archiv/Formulations2015/Cos1510_Clariant.pdf Clariant Skin Renewal Treatment http://www.cossma.com/fileadmin/all/cossma/Archiv/Formulations2015/Cos1510_CLR.pdf CLR Pore Refining Anti Age Day -

Differences. CM BEST COPY AVAILABLE

DOCUMENT RESUME ID 100 112 EC 070 982 MLR Project Child Ten Kit 3: Characteristicsof the Language Disabled Child. INSTITUTION Texas Education Agency, Austin. NOTE 51p.; For related information see EC 070975-992 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$3.15 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS *Behavioral Objectives; Exceptional Child Education; Instructional Materials; *Language Handicapped; Learning Disabilities; *Performance Based Teacher Education; Performance Criteria; *Student Characteristics IDENTIFIERS *Project CHILD ABSTRACT Presented is the third of 12 instructional kits, on characteristics of the language disabled (LD) child, for a performance based teacher education program which was developed by Project CHILD, a research effort to validate identification, intervention, and teacher education programs for LD children. Included in the kit are directions for preassessment tasks for the five performance objectives, a listing of the five performance objectives (such as correctly identifying three learning disabled children from five case histories), instructions for four learning experiences (such as using correct terminology to identify pantomimed behavior characteristics), a checklist for self-evaluation for each of the performance objectives, and guidelines for proficiency assessment of each objective. Also included are two descriptions of LD children intended to help the student identify individual differences. CM BEST COPY AVAILABLE PROJECT CHILD U.S. DEPARTMENT OP HEALTH, EDUCATION A WELFARE NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRO DUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGIN Ten Kit 3 ATOM IT POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRE SENT OFFICIAL NATIONAL INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY Texas Education Agency Austin, Texas 4 Texas Education Agency publications are not copyrighted. -

Summer Beauty School 2019

Summer Ma2019keup Course Graduation Requirements Attend all classes with at least 1 different guest each time Write down date of the class attended, include your guest's name, and get your director's signature Class 1 date: _________ Guest:_________ Class 2 date: _________ Guest:_________ Class 3 date: _________ Guest:_________ Class 4 date: _________ Guest:_________ Class 5 date: _________ Guest:_________ Class 1: Prep Your Skin Notes: All makeup looks better when it’s on healthy, well cared for skin. Moisturized skin looks radiant with makeup. On the contrary, your makeup tends to look dull. A Foundation Primer with SPF 15 diminishes visable imperfections and protects you from the sun. Conceal Correct Set Conceal blemishes, age spots Conceal blemishes, age Helps set makeup, reduce and minor skin imperfections. spots, and minor skin shine and create a imperfections. matte finish. Long-lasting, lightweight formula and creaseproof Neutralize dark circles Translucent powder is great coverage. beneath the eyes . for any skin tone. Light-diffusing technology Helps blur the Pressed powder can helps blur the appearance of appearance of fine lines. be applied lightly or pressed fine lines. into skin for more coverage. Helps hide redness. Helps hide the appearance of As a final step, Finishing redness. Spray keeps makeup looking freshly applied. Gives 16 Suitable for sensitive skin, hours staying power. including skin around the delicate eye area. Choose your coverage and your tool Foundation Conversion Chart Class 2: Eye Brows & Eyeliners Notes: Brush, Define and Fill your Brows The wired spoolie end tames Defines brows with hairlike Gives volume and tames brows. -

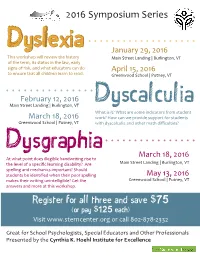

2016 Symposium Series

2016 Symposium Series Dyslexia January 29, 2016 This workshop will review the history Main Street Landing | Burlington, VT of the term, its status in the law, early signs of risk, and what educators can do April 15, 2016 to ensure that all children learn to read. Greenwood School | Putney, VT February 12, 2016 Dyscalculia Main Street Landing | Burlington, VT What is it? What are some indicators from student March 18, 2016 work? How can we provide support for students Greenwood School | Putney, VT with dyscalculia and other math difficulties? Dysgrap hia March 18, 2016 At what point does illegible handwriting rise to the level of a specific learning disability? Are Main Street Landing | Burlington, VT spelling and mechanics important? Should students be identified when their poor spelling May 13, 2016 makes their writing unintelligible? Get the Greenwood School | Putney, VT answers and more at this workshop. Register for all three and save $75 (or pay $125 each) Visit www.sterncenter.org or call 802-878-2332 Great for School Psychologists, Special Educators and Other Professionals Presented by the Cynthia K. Hoehl Institute for Excellence Friday, April 15, 2016 Dyslexia Greenwood School | Putney, Vermont The field of reading is rife with About the Presenter controversy. We not only disagree over Melissa Farrall, Ph.D. what constitutes a reading disorder, we is the author of Reading often bristle over the language that others Assessment: Linking Language, Literacy, and Cognition, use to describe one. The term, dyslexia, and the co-author of All elicits a wide range of reactions. About Tests & Assessments published by Wrightslaw. -

Ventas En El Primer Trimestre De 2021

Clichy, 15 de abril de 2021 a las 6.00 p.m. VENTAS EN EL PRIMER TRIMESTRE DE 2021 FUERTE REGRESO AL CRECIMIENTO AL +10.2 % 1 ➢ Ventas: 7.61 mil millones de euros o +10.2 % like-for-like 1 o +11.5 % con tipos de cambio constantes o +5.4 % con base en las cifras reportadas ➢ Significativamente superior en el mercado ➢ Tres divisiones con crecimiento mayor de dos dígitos ➢ Crecimiento notable en el Pacífico Asiático de +23.8 %1, impulsado por China peninsular de +37.9% 1 ➢ Fuerte recuperación en América del Norte ➢ Crecimiento del comercio en línea de +47.2 % 2 Con respecto a las cifras, el Sr. Jean-Paul Agon, Presidente y Director general de L'Oréal, comentó: “A pesar de la crisis sanitaria y de las medidas pertinentes que se están tomando en la actualidad en algunos países, en particular en Europa occidental, el mercado de la belleza sigue recuperándose. En vista de este escenario, L’Oréal ha empezado el año con un crecimiento muy fuerte de +10.2 % like-for-like 1 en el primer trimestre, con lo que es significativamente superior en el mercado. Es por ello que el Grupo continúa con su incremento, la cual inició en el tercer trimestre de 2020 y está aumentando en +5.0 % like-for-like en comparación con el primer trimestre de 2019. El desempeño de las divisiones Productos Profesionales, L’Oréal Luxe y Cosmética Activa es extraordinario, pues todas presentan un crecimiento de dos dígitos. La división Productos Profesionales está contabilizando un crecimiento significativo en todo el mundo. -

3.11 Chemistry of Cosmetics Masahiro Ota and Mineyuki Yokoyama, Shiseido Co., Ltd., Yokohama, Japan

3.11 Chemistry of Cosmetics Masahiro Ota and Mineyuki Yokoyama, Shiseido Co., Ltd., Yokohama, Japan ª 2010 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. 3.11.1 Introduction 317 3.11.2 History of Cosmetics and Natural Products 317 3.11.3 Pharmaceutical Affairs Law in Japan and Its Relevance to Natural Products 319 3.11.4 Skin-Whitening Cosmetics 322 3.11.5 Antiaging Cosmetics 327 3.11.6 Hair Growth Promoters 333 3.11.7 Plant Cell/Tissue Culture Technology for Natural Products in Cosmetics 337 3.11.7.1 Potential of Plant Cell/Tissue Culture for Cosmetic Application 337 3.11.7.2 Micropropagation 339 3.11.7.3 Root Culture 340 3.11.7.4 Biotransformation Techniques with Plant Cell Culture 341 3.11.7.5 Miscellaneous 345 3.11.8 Conclusion 346 References 347 3.11.1 Introduction Cosmetics have a deep relation to natural products. It is true that there are many cosmetic products that have catchphrases or selling points claiming 100% pure natural ingredients; however, it is impossible to make cosmetics without natural products, regardless of such catchphrases. Hence, as regards natural products, no one is in doubt about the notion that they are something that cannot be done away with in cosmetics. The role of natural products in medicines is as one of the sources of lead compounds in the research and development of modern medicines, but in cosmetics natural products themselves are combined as ingredients, although there may be similar cases in medical research process too. In general the categories of cosmetics are limited only by people’s imagination.