Identification and Valuation of Embedded Derivatives in Modified Coinsurance and Similar Insurance Arrangements

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Federal Register/Vol. 84, No. 215/Wednesday, November 6

Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 215 / Wednesday, November 6, 2019 / Notices 59849 respect to this action, see the each participant will speak, and the SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE application for license amendment time allotted for each presentation. COMMISSION dated October 23, 2019. A written summary of the hearing will [Release No. 34–87434; File No. SR– Attorney for licensee: General be compiled, and such summary will be NYSEArca–2019–12] Counsel, Tennessee Valley Authority, made available, upon written request to 400 West Summit Hill Drive, 6A West OPIC’s Corporate Secretary, at the cost Self-Regulatory Organizations; NYSE Tower, Knoxville, TN 37902. of reproduction. Arca, Inc.; Notice of Filing of NRC Branch Chief: Undine Shoop. Amendment No. 2 and Order Granting Written summaries of the projects to Accelerated Approval of a Proposed Dated at Rockville, Maryland, this 31st day be presented at the December 11, 2019, of October 2019. Rule Change, as Modified by Board meeting will be posted on OPIC’s Amendment No. 2, To List and Trade For the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. website. Kimberly J. Green, Shares of the iShares Commodity Senior Project Manager, Plant Licensing CONTACT PERSON FOR INFORMATION: Curve Carry Strategy ETF Under NYSE Branch II–2, Division of Operating Reactor Information on the hearing may be Arca Rule 8.600–E obtained from Catherine F. I. Andrade at Licensing, Office of Nuclear Reactor I. Introduction Regulation. (202) 336–8768, via facsimile at (202) [FR Doc. 2019–24198 Filed 11–5–19; 8:45 am] 408–0297, or via email at On March 1, 2019, NYSE Arca, Inc. -

Total Return Swap • Exchange the Total Economic Performance of a Specific Asset for Another Cash Flow

Total return swap • Exchange the total economic performance of a specific asset for another cash flow. total return of asset Total return Total return payer receiver LIBOR + Y bp Total return comprises the sum of interests, fees and any change-in-value payments with respect to the reference asset. A commercial bank can hedge all credit risk on a loan it has originated. The counterparty can gain access to the loan on an off-balance sheet basis, without bearing the cost of originating, buying and administering the loan. 1 The payments received by the total return receiver are: 1. The coupon c of the bond (if there were one since the last payment date Ti − 1) + 2. The price appreciation ( C ( T i ) − C ( T i − 1 ) ) of the underlying bond C since the last payment (if there were only). 3. The recovery value of the bond (if there were default). The payments made by the total return receiver are: 1. A regular fee of LIBOR + sTRS + 2. The price depreciation ( C ( T i − 1 ) − C ( T i ) ) of bond C since the last payment (if there were only). 3. The par value of the bond C if there were a default in the meantime). The coupon payments are netted and swap’s termination date is earlier than bond’s maturity. 2 Some essential features 1. The receiver is synthetically long the reference asset without having to fund the investment up front. He has almost the same payoff stream as if he had invested in risky bond directly and funded this investment at LIBOR + sTRS. -

Credit Derivatives

3 Credit Derivatives CHAPTER 7 Credit derivatives Collaterized debt obligation Credit default swap Credit spread options Credit linked notes Risks in credit derivatives Credit Derivatives •A credit derivative is a financial instrument whose value is determined by the default risk of the principal asset. •Financial assets like forward, options and swaps form a part of Credit derivatives •Borrowers can default and the lender will need protection against such default and in reality, a credit derivative is a way to insure such losses Credit Derivatives •Credit default swaps (CDS), total return swap, credit default swap options, collateralized debt obligations (CDO) and credit spread forwards are some examples of credit derivatives •The credit quality of the borrower as well as the third party plays an important role in determining the credit derivative’s value Credit Derivatives •Credit derivatives are fundamentally divided into two categories: funded credit derivatives and unfunded credit derivatives. •There is a contract between both the parties stating the responsibility of each party with regard to its payment without resorting to any asset class Credit Derivatives •The level of risk differs in different cases depending on the third party and a fee is decided based on the appropriate risk level by both the parties. •Financial assets like forward, options and swaps form a part of Credit derivatives •The price for these instruments changes with change in the credit risk of agents such as investors and government Credit derivatives Collaterized debt obligation Credit default swap Credit spread options Credit linked notes Risks in credit derivatives Collaterized Debt obligation •CDOs or Collateralized Debt Obligation are financial instruments that banks and other financial institutions use to repackage individual loans into a product sold to investors on the secondary market. -

Commodity Index Traders and the Boom/Bust Cycle in Commodities Prices

Page 2 Commodity Index Traders and the Boom/Bust Cycle in Commodities Prices David Frenk and Wallace Turbeville* ©Better Markets 2011 ABSTRACT Since 2005, the public has lived with high and volatile prices for basic energy and agricultural commodities. The public focus on this unprecedented commodity price volatility has been intense, because a large proportion of the cost of living borne by individuals and families in the U.S. (and around the globe) is represented by commodities- based costs, notably food, fuel, and clothing. Interestingly, as commodity prices have shown more price volatility, there has been an accompanying significant increase in the volume of commodities futures and swaps transactions, as well as commodities markets open interest. Moreover, Commodity Index Traders (“CITs”), a relatively new type of participant, now collectively make up the single largest group of non-commercial participants in commodities futures markets. These CITs, which represent giant institutional pools of capital, have at times been the single largest class of participant, outweighing bona fide hedgers (producers and consumers of commodities) and traditional “speculators,” who take short-term bi-directional bets and provide liquidity. Given both the size and the specific and largely homogeneous investment strategy of the CITs, many market observers have concluded that this group is most likely responsible for greatly disrupting price formation in commodities futures markets. Further, it has been posited that this distortion has directly led to -

Consolidated Policy on Valuation Adjustments Global Capital Markets

Global Consolidated Policy on Valuation Adjustments Consolidated Policy on Valuation Adjustments Global Capital Markets September 2008 Version Number 2.35 Dilan Abeyratne, Emilie Pons, William Lee, Scott Goswami, Jerry Shi Author(s) Release Date September lOth 2008 Page 1 of98 CONFIDENTIAL TREATMENT REQUESTED BY BARCLAYS LBEX-BARFID 0011765 Global Consolidated Policy on Valuation Adjustments Version Control ............................................................................................................................. 9 4.10.4 Updated Bid-Offer Delta: ABS Credit SpreadDelta................................................................ lO Commodities for YH. Bid offer delta and vega .................................................................................. 10 Updated Muni section ........................................................................................................................... 10 Updated Section 13 ............................................................................................................................... 10 Deleted Section 20 ................................................................................................................................ 10 Added EMG Bid offer and updated London rates for all traded migrated out oflens ....................... 10 Europe Rates update ............................................................................................................................. 10 Europe Rates update continue ............................................................................................................. -

Merger Arbitrage Today Offering Consistency in Uncertain Markets a Differentiated Return Stream

Ψ The Arbitrage Funds advised by water island capital Merger Arbitrage Today Offering Consistency in Uncertain Markets A Differentiated Return Stream In Times of Equity Market Stress Merger Arbitrage is a time-tested strategy that has historically provided returns 100% uncorrelated to broader swings in the market. During times of market stress, the Percentage of time strategy may provide an important source of diversification for an investor’s portfolio. Merger Arbitrage outperformed Stocks average return average return in months Stocks in months stocks are down in years stocks are down were down. 5% 3.29% Source: Morningstar; Date range: 1/1/10-12/31/19. 0% -0.25% -3.28% -5% -4.38% Merger Arbitrage Stocks Source: Morningstar. Date Range: 1/1/10-12/31/19. Past performance does not guarantee future results. “Merger Arbitrage” represented by HFRI Merger Arbitrage. “Stocks” represented by S&P 500. Index returns are for illustrative purposes only and do not represent actual performance. S&P 500 returns do not reflect any management fees, transaction costs, or expenses. Indices are unmanaged and one cannot invest directly in an index. Greater Levels of Volatility Because returns are closely tied to the outcome of specific, short-term events, rather -21% than overall market direction, volatility can offer attractive entry points. It can also lead to the re-pricing of risk, allowing for greater return potential. Merger Arbitrage VIX five-year average relative to its historic performance has historically been better than Stocks when market volatility increases. average. sum of daily returns on days when the vix is above or below its average level VIX Avg/Historical Avg 120% 108% -20% 2019 100% -13% 2018 80% 40% -42% 2017 20% 8% 5% -17% 2016 0% -13% 2015 -20% -40% Source: CBOE; Water Island Capital. -

Migration Plan of Risky Total Return Swap to Bond Return Swap

DEGREE PROJECT IN ENGINEERING PHYSICS, SECOND CYCLE, 30 CREDITS STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN 2020 Migration plan of Risky Total Return Swap to Bond Return Swap LOUIS MAZIERE KTH ROYAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING SCIENCES Migration plan of Risky Total Return Swap to Bond Return Swap LOUIS MAZIERE Degree Projects in Financial Mathematics (30 ECTS credits) Degree Programme in Engineering Physics KTH Royal Institute of Technology year 2020 Supervisor at Murex: Pierre Moureaux and Sabine Farhat Supervisor at KTH: Boualem Djehiche Examiner at KTH: Boualem Djehiche TRITA-SCI-GRU 2020:030 MAT-E 2020:008 Royal Institute of Technology School of Engineering Sciences KTH SCI SE-100 44 Stockholm, Sweden URL: www.kth.se/sci 2 Abstract Since the 2008 crisis, the hedging instruments have gained popularity with financial institutions. This is the case of the total return swap that is used today by major institutions like Goldman Sachs or J.P. Morgan. Murex is a software provider for financial institutions. The company already had a total return swap product, the RTRS (for Risky Total Return Swap), but with the growing demand Murex decided to develop a new product, the BRS (Bond Return Swap). So now they have two bond total return swaps. This master thesis aims to analyze total return swap and highlight the improvement of the BRS. After a theoretical analysis of the total return swap, a test campaign is realized. For different types of bond and different configurations of total return swap, formulas are derived to be compared to the returned values. The results given by the RTRS are good on basic bonds. -

Financial Statements Of

Condensed Consolidated Interim Financial Statements of CARGOJET INC. For the three and nine month periods ended September 30, 2018 and 2017 (unaudited - expressed in millions of Canadian dollars) This page intentionally left blank CARGOJET INC. Condensed Consolidated Interim Balance Sheets As at September 30, 2018 and December 31, 2017 (unaudited, in millions of Canadian dollars) September 30, December 31, Note 2018 2017 $ $ ASSETS CURRENT ASSETS Cash - 5.7 Trade and other receivables 42.6 40.1 Inventories 1.1 0.9 Prepaid expenses and deposits 10.3 5.8 Income taxes recoverable 0.1 0.1 Derivative financial instruments 16 1.0 1.8 55.1 54.4 NON-CURRENT ASSETS Property, plant and equipment 4, 6 650.7 514.7 Goodwill 46.4 46.4 Intangible assets 2.0 2.0 Deposits 3.3 5.7 Deferred income taxes 10 4.7 4.5 762.2 627.7 LIABILITIES CURRENT LIABILITIES Overdraft 2.4 - Trade and other payables 36.1 38.1 Finance leases 7 15.0 62.1 Provisions 8 1.4 0.1 Dividends payable 2.8 2.6 Derivative financial instruments 16 0.1 1.6 57.8 104.5 NON-CURRENT LIABILITIES Borrowings 6 268.3 124.5 Finance leases 7 128.0 99.1 Provisions 8 - 1.2 Convertible debentures 9 116.5 114.8 Deferred income taxes 10 25.4 18.5 Employees pension and option liability 5 14.7 10.5 610.7 473.1 EQUITY 151.5 154.6 762.2 627.7 The accompanying notes are an integral component of these condensed consolidated interim financial statements. -

HAP Nexus Hedge Fund Replication Trust

Annual Report | December 31, 2015 HAP Nexus Hedge Fund Replication Trust Innovation is our capital. Make it yours. www.HorizonsETFs.com ALPHA BENCHMARK BETAPRO 87726 - HAP Nexus Hedge.indd 1 2016-03-04 3:57 PM Contents MANAGEMENT REPORT OF FUND PERFORMANCE Management Discussion of Fund Performance .....................1 Financial Highlights ...............................................6 Past Performance ..................................................9 Summary of Investment Portfolio . 11 MANAGER’S RESPONSIBILITY FOR FINANCIAL REPORTING ............13 INDEPENDENT AUDITORS’ REPORT. 14 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Statements of Financial Position ..................................15 Statements of Comprehensive Income ............................16 Statements of Changes in Financial Position .......................17 Statements of Cash Flows .........................................18 Schedule of Investments ..........................................19 Notes to Financial Statements ....................................21 87726 - HAP Nexus Hedge.indd 3 2016-03-04 3:57 PM Letter from the Co-CEO: The story for investors in 2015 was one of a return to volatility, especially in the North American markets. Canadian equities declined noticeably and in the U.S., the S&P 500® experienced its first 10% correction in over three years, only to rally to end the year with a modest loss. Additionally, the Canadian Dollar had its worst performing year relative to the U.S. Dollar since 2008 and we saw very marginal returns from the fixed income markets. For Horizons ETFs, this year could be called “The Year of the Active ETF,” since many of our actively managed equity and fixed income ETFs delivered strong relative returns. Portfolio managers who can identify sectors or individual securities with better relative returns can, and do, deliver attractive results, assuming they are not burdened with the high management fees that can plague many actively managed mutual funds. -

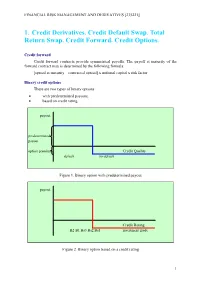

1. Credit Derivatives. Credit Default Swap. Total Return Swap. Credit Forward

FINANCIAL RISK MANAGEMENT AND DERIVATIVES [235221] 1. Credit Derivatives. Credit Default Swap. Total Return Swap. Credit Forward. Credit Options. Credit forward Credit forward contracts provide symmetrical payoffs. The payoff at maturity of the forward contract may is determined by the following formula: [spread at maturity – contracted spread] x notional capital x risk factor Binary credit options There are two types of binary options with predetermined payouts, based on credit rating. payout predetermined payout option premium Credit Quality default no default Figure 1. Binary option with predetermined payout payout Credit Rating B2 B1 Ba3 Ba2 Ba1 investment grade Figure 2. Binary option based on a credit rating 1 FINANCIAL RISK MANAGEMENT AND DERIVATIVES [235221] Credit Swaps Cash Payment if Credit risky Investment Credit Default Dealer Z assets protection (credit buyer protection (bank Y) seller) Total return Swap Premium Figure 3. Credit Default Swap with a Cash Payment Upon Default Credit risky Investment Credit LIBOR + spread Dealer Z assets protection (credit buyer protection (bank Y) seller) Total return Total return Figure 4. Credit Default Swap with a Periodic Payment Investor 1 Payment for a credit event associated Investor 2 Bond A with bond A Bond B Payment for a credit event associated with bond A 2 FINANCIAL RISK MANAGEMENT AND DERIVATIVES [235221] Figure 5. Reciprocal Credit Default Swap Total Return Swap Credit risky Investment Credit LIBOR + spread Investor Y assets protection (credit risk buyer buyer) (dealer Z) Total return Total return Figure 6. Total Return Credit Swap 3 FINANCIAL RISK MANAGEMENT AND DERIVATIVES [235221] Problem 1. Credit Forward Bank Y buys a credit spread forward. -

Horizons Morningstar Hedge Fund Index ETF (HHF, HHF.A:TSX)

Annual Report | December 31, 2015 Horizons Morningstar Hedge Fund Index ETF (HHF, HHF.A:TSX) Innovation is our capital. Make it yours. www.HorizonsETFs.com ALPHA BENCHMARK BETAPRO 87725 - Horizons HHF.indd 1 2016-03-04 3:54 PM Contents MANAGEMENT REPORT OF FUND PERFORMANCE Management Discussion of Fund Performance ..........................................1 Financial Highlights ....................................................................7 Past Performance ......................................................................10 Summary of Investment Portfolio of Horizons Morningstar Hedge Fund Index ETF .......12 Summary of Investment Portfolio of HAP Nexus Hedge Fund Replication Trust ..........13 MANAGER’S RESPONSIBILITY FOR FINANCIAL REPORTING .................................15 INDEPENDENT AUDITORS’ REPORT. .16 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Statements of Financial Position .......................................................17 Statements of Comprehensive Income .................................................18 Statements of Changes in Financial Position ............................................19 Statements of Cash Flows ..............................................................20 Schedule of Investments of Horizons Morningstar Hedge Fund Index ETF ...............21 Schedule of Investments of HAP Nexus Hedge Fund Replication Trust. 22 Notes to Financial Statements .........................................................24 87725 - Horizons HHF.indd 3 2016-03-04 3:54 PM Letter from the Co-CEO: The story for investors in 2015 -

A Guide to Alternative Investments

A GUIDE TO ALTERNATIVE INVESTMENTS Learn the key terms to help you navigate this important segment of the financial services industry CIBC ASSET MANAGEMENT A guide to alternative investments The alternative investments space is a dynamic and rapidly evolving segment of the financial services industry. While alternative investments in the past have been principally the domain of institutional and accredited investors, this market segment is becoming increasingly available to a wider range of investors, through such vehicles as liquid alternatives. The landscape can be much easier to navigate once you become familiar with some common terms that are often used within this space. This guide contains explanations of various aspects of alternative investments, so keep it handy whenever you’re taking a closer look at different alternative investment strategies to include in an investment portfolio. What are alternative investments? Strategies that go beyond traditional investments (such as stocks, bonds or cash) Alternatives are investments in assets other than stocks, bonds and cash (for example, private equity, hedge funds, real assets, commodities, etc,) or investments using strategies that go beyond traditional ways of investing (such as long/short strategies) They provide more options for investors to increase their sources of returns, improve portfolio diversification and manage risk Investors can access alternatives more easily now through a fast-growing market segment known as liquid alternatives: alternative investments in the form of a mutual fund or exchange-traded fund, which offer the additional benefit of daily pricing Liquid alternatives provide investors with a flexible investment approach through exposure to various asset classes and strategies A GUIDE TO ALTERNATIVE INVESTMENTS | 2 CIBC ASSET MANAGEMENT A glossary of common terms Alpha The excess return an investment achieves over its benchmark is known as alpha.