Commodity Index Traders and the Boom/Bust Cycle in Commodities Prices

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interest Rate Options

Interest Rate Options Saurav Sen April 2001 Contents 1. Caps and Floors 2 1.1. Defintions . 2 1.2. Plain Vanilla Caps . 2 1.2.1. Caplets . 3 1.2.2. Caps . 4 1.2.3. Bootstrapping the Forward Volatility Curve . 4 1.2.4. Caplet as a Put Option on a Zero-Coupon Bond . 5 1.2.5. Hedging Caps . 6 1.3. Floors . 7 1.3.1. Pricing and Hedging . 7 1.3.2. Put-Call Parity . 7 1.3.3. At-the-money (ATM) Caps and Floors . 7 1.4. Digital Caps . 8 1.4.1. Pricing . 8 1.4.2. Hedging . 8 1.5. Other Exotic Caps and Floors . 9 1.5.1. Knock-In Caps . 9 1.5.2. LIBOR Reset Caps . 9 1.5.3. Auto Caps . 9 1.5.4. Chooser Caps . 9 1.5.5. CMS Caps and Floors . 9 2. Swap Options 10 2.1. Swaps: A Brief Review of Essentials . 10 2.2. Swaptions . 11 2.2.1. Definitions . 11 2.2.2. Payoff Structure . 11 2.2.3. Pricing . 12 2.2.4. Put-Call Parity and Moneyness for Swaptions . 13 2.2.5. Hedging . 13 2.3. Constant Maturity Swaps . 13 2.3.1. Definition . 13 2.3.2. Pricing . 14 1 2.3.3. Approximate CMS Convexity Correction . 14 2.3.4. Pricing (continued) . 15 2.3.5. CMS Summary . 15 2.4. Other Swap Options . 16 2.4.1. LIBOR in Arrears Swaps . 16 2.4.2. Bermudan Swaptions . 16 2.4.3. Hybrid Structures . 17 Appendix: The Black Model 17 A.1. -

The Synthetic Collateralised Debt Obligation: Analysing the Super-Senior Swap Element

The Synthetic Collateralised Debt Obligation: analysing the Super-Senior Swap element Nicoletta Baldini * July 2003 Basic Facts In a typical cash flow securitization a SPV (Special Purpose Vehicle) transfers interest income and principal repayments from a portfolio of risky assets, the so called asset pool, to a prioritized set of tranches. The level of credit exposure of every single tranche depends upon its level of subordination: so, the junior tranche will be the first to bear the effect of a credit deterioration of the asset pool, and senior tranches the last. The asset pool can be made up by either any type of debt instrument, mainly bonds or bank loans, or Credit Default Swaps (CDS) in which the SPV sells protection1. When the asset pool is made up solely of CDS contracts we talk of ‘synthetic’ Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs); in the so called ‘semi-synthetic’ CDOs, instead, the asset pool is made up by both debt instruments and CDS contracts. The tranches backed by the asset pool can be funded or not, depending upon the fact that the final investor purchases a true debt instrument (note) or a mere synthetic credit exposure. Generally, when the asset pool is constituted by debt instruments, the SPV issues notes (usually divided in more tranches) which are sold to the final investor; in synthetic CDOs, instead, tranches are represented by basket CDSs with which the final investor sells protection to the SPV. In any case all the tranches can be interpreted as percentile basket credit derivatives and their degree of subordination determines the percentiles of the asset pool loss distribution concerning them It is not unusual to find both funded and unfunded tranches within the same securitisation: this is the case for synthetic CDOs (but the same could occur with semi-synthetic CDOs) in which notes are issued and the raised cash is invested in risk free bonds that serve as collateral. -

Ice Crude Oil

ICE CRUDE OIL Intercontinental Exchange® (ICE®) became a center for global petroleum risk management and trading with its acquisition of the International Petroleum Exchange® (IPE®) in June 2001, which is today known as ICE Futures Europe®. IPE was established in 1980 in response to the immense volatility that resulted from the oil price shocks of the 1970s. As IPE’s short-term physical markets evolved and the need to hedge emerged, the exchange offered its first contract, Gas Oil futures. In June 1988, the exchange successfully launched the Brent Crude futures contract. Today, ICE’s FSA-regulated energy futures exchange conducts nearly half the world’s trade in crude oil futures. Along with the benchmark Brent crude oil, West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude oil and gasoil futures contracts, ICE Futures Europe also offers a full range of futures and options contracts on emissions, U.K. natural gas, U.K power and coal. THE BRENT CRUDE MARKET Brent has served as a leading global benchmark for Atlantic Oseberg-Ekofisk family of North Sea crude oils, each of which Basin crude oils in general, and low-sulfur (“sweet”) crude has a separate delivery point. Many of the crude oils traded oils in particular, since the commercialization of the U.K. and as a basis to Brent actually are traded as a basis to Dated Norwegian sectors of the North Sea in the 1970s. These crude Brent, a cargo loading within the next 10-21 days (23 days on oils include most grades produced from Nigeria and Angola, a Friday). In a circular turn, the active cash swap market for as well as U.S. -

Tax Treatment of Derivatives

United States Viva Hammer* Tax Treatment of Derivatives 1. Introduction instruments, as well as principles of general applicability. Often, the nature of the derivative instrument will dictate The US federal income taxation of derivative instruments whether it is taxed as a capital asset or an ordinary asset is determined under numerous tax rules set forth in the US (see discussion of section 1256 contracts, below). In other tax code, the regulations thereunder (and supplemented instances, the nature of the taxpayer will dictate whether it by various forms of published and unpublished guidance is taxed as a capital asset or an ordinary asset (see discus- from the US tax authorities and by the case law).1 These tax sion of dealers versus traders, below). rules dictate the US federal income taxation of derivative instruments without regard to applicable accounting rules. Generally, the starting point will be to determine whether the instrument is a “capital asset” or an “ordinary asset” The tax rules applicable to derivative instruments have in the hands of the taxpayer. Section 1221 defines “capital developed over time in piecemeal fashion. There are no assets” by exclusion – unless an asset falls within one of general principles governing the taxation of derivatives eight enumerated exceptions, it is viewed as a capital asset. in the United States. Every transaction must be examined Exceptions to capital asset treatment relevant to taxpayers in light of these piecemeal rules. Key considerations for transacting in derivative instruments include the excep- issuers and holders of derivative instruments under US tions for (1) hedging transactions3 and (2) “commodities tax principles will include the character of income, gain, derivative financial instruments” held by a “commodities loss and deduction related to the instrument (ordinary derivatives dealer”.4 vs. -

An Analysis of OTC Interest Rate Derivatives Transactions: Implications for Public Reporting

Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports An Analysis of OTC Interest Rate Derivatives Transactions: Implications for Public Reporting Michael Fleming John Jackson Ada Li Asani Sarkar Patricia Zobel Staff Report No. 557 March 2012 Revised October 2012 FRBNY Staff REPORTS This paper presents preliminary fi ndings and is being distributed to economists and other interested readers solely to stimulate discussion and elicit comments. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and are not necessarily refl ective of views at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors. An Analysis of OTC Interest Rate Derivatives Transactions: Implications for Public Reporting Michael Fleming, John Jackson, Ada Li, Asani Sarkar, and Patricia Zobel Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 557 March 2012; revised October 2012 JEL classifi cation: G12, G13, G18 Abstract This paper examines the over-the-counter (OTC) interest rate derivatives (IRD) market in order to inform the design of post-trade price reporting. Our analysis uses a novel transaction-level data set to examine trading activity, the composition of market participants, levels of product standardization, and market-making behavior. We fi nd that trading activity in the IRD market is dispersed across a broad array of product types, currency denominations, and maturities, leading to more than 10,500 observed unique product combinations. While a select group of standard instruments trade with relative frequency and may provide timely and pertinent price information for market partici- pants, many other IRD instruments trade infrequently and with diverse contract terms, limiting the impact on price formation from the reporting of those transactions. -

Federal Register/Vol. 84, No. 215/Wednesday, November 6

Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 215 / Wednesday, November 6, 2019 / Notices 59849 respect to this action, see the each participant will speak, and the SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE application for license amendment time allotted for each presentation. COMMISSION dated October 23, 2019. A written summary of the hearing will [Release No. 34–87434; File No. SR– Attorney for licensee: General be compiled, and such summary will be NYSEArca–2019–12] Counsel, Tennessee Valley Authority, made available, upon written request to 400 West Summit Hill Drive, 6A West OPIC’s Corporate Secretary, at the cost Self-Regulatory Organizations; NYSE Tower, Knoxville, TN 37902. of reproduction. Arca, Inc.; Notice of Filing of NRC Branch Chief: Undine Shoop. Amendment No. 2 and Order Granting Written summaries of the projects to Accelerated Approval of a Proposed Dated at Rockville, Maryland, this 31st day be presented at the December 11, 2019, of October 2019. Rule Change, as Modified by Board meeting will be posted on OPIC’s Amendment No. 2, To List and Trade For the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. website. Kimberly J. Green, Shares of the iShares Commodity Senior Project Manager, Plant Licensing CONTACT PERSON FOR INFORMATION: Curve Carry Strategy ETF Under NYSE Branch II–2, Division of Operating Reactor Information on the hearing may be Arca Rule 8.600–E obtained from Catherine F. I. Andrade at Licensing, Office of Nuclear Reactor I. Introduction Regulation. (202) 336–8768, via facsimile at (202) [FR Doc. 2019–24198 Filed 11–5–19; 8:45 am] 408–0297, or via email at On March 1, 2019, NYSE Arca, Inc. -

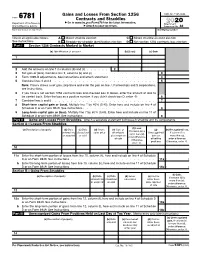

Form 6781 Contracts and Straddles ▶ Go to for the Latest Information

Gains and Losses From Section 1256 OMB No. 1545-0644 Form 6781 Contracts and Straddles ▶ Go to www.irs.gov/Form6781 for the latest information. 2020 Department of the Treasury Attachment Internal Revenue Service ▶ Attach to your tax return. Sequence No. 82 Name(s) shown on tax return Identifying number Check all applicable boxes. A Mixed straddle election C Mixed straddle account election See instructions. B Straddle-by-straddle identification election D Net section 1256 contracts loss election Part I Section 1256 Contracts Marked to Market (a) Identification of account (b) (Loss) (c) Gain 1 2 Add the amounts on line 1 in columns (b) and (c) . 2 ( ) 3 Net gain or (loss). Combine line 2, columns (b) and (c) . 3 4 Form 1099-B adjustments. See instructions and attach statement . 4 5 Combine lines 3 and 4 . 5 Note: If line 5 shows a net gain, skip line 6 and enter the gain on line 7. Partnerships and S corporations, see instructions. 6 If you have a net section 1256 contracts loss and checked box D above, enter the amount of loss to be carried back. Enter the loss as a positive number. If you didn’t check box D, enter -0- . 6 7 Combine lines 5 and 6 . 7 8 Short-term capital gain or (loss). Multiply line 7 by 40% (0.40). Enter here and include on line 4 of Schedule D or on Form 8949. See instructions . 8 9 Long-term capital gain or (loss). Multiply line 7 by 60% (0.60). Enter here and include on line 11 of Schedule D or on Form 8949. -

To: Distributors and Holders of Minibonds Minibonds in The

To: Distributors and holders of Minibonds Minibonds In the following, we provide answers to some questions which apply generally to the Minibonds, but holders should be aware that each series of Minibonds is different and the status of their series may therefore differ in some respects from the general answers given here. The structure of the Minibonds and the rights of holders are explained more fully in the prospectuses for the issues See the section of the issue prospectuses headed “Information about us and how our Notes are secured” for a general description of the collateral and the swap arrangements.. What is the current status of Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc.? On 15 September 2008 Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. (“LBHI”) filed a petition (the “Petition”) under Chapter 11 of the U.S. Bankruptcy Code with the United States Bankruptcy Court of the Southern District of New York. What is the role of Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. in the Minibonds? LBHI is the swap guarantor for the Minibonds and is the guarantor of the collateral for some early series of Minibonds. The swap counterparties for the Minibonds are wholly-owned subsidiaries of LBHI. How does this affect the Minibonds? According to ISDA (the International Swaps and Derivatives Association Inc., an industry body), the filing of the Petition constitutes an event of default under swaps such as the swap arrangements which Pacific International Finance Limited, the issuer of the Minibonds, has entered into with Lehman. This means that the Minibonds will, subject to conditions and to a number of other procedures, be subject to early redemption unless the trustee for the Minibonds directs otherwise. -

Inflation Derivatives: Introduction One of the Latest Developments in Derivatives Markets Are Inflation- Linked Derivatives, Or, Simply, Inflation Derivatives

Inflation-indexed Derivatives Inflation derivatives: introduction One of the latest developments in derivatives markets are inflation- linked derivatives, or, simply, inflation derivatives. The first examples were introduced into the market in 2001. They arose out of the desire of investors for real, inflation-linked returns and hedging rather than nominal returns. Although index-linked bonds are available for those wishing to have such returns, as we’ve observed in other asset classes, inflation derivatives can be tailor- made to suit specific requirements. Volume growth has been rapid during 2003, as shown in Figure 9.4 for the European market. 4000 3000 2000 1000 0 Jul 01 Jul 02 Jul 03 Jan 02 Jan 03 Sep 01 Sep 02 Mar 02 Mar 03 Nov 01 Nov 02 May 01 May 02 May 03 Figure 9.4 Inflation derivatives volumes, 2001-2003 Source: ICAP The UK market, which features a well-developed index-linked cash market, has seen the largest volume of business in inflation derivatives. They have been used by market-makers to hedge inflation-indexed bonds, as well as by corporates who wish to match future liabilities. For instance, the retail company Boots plc added to its portfolio of inflation-linked bonds when it wished to better match its future liabilities in employees’ salaries, which were assumed to rise with inflation. Hence, it entered into a series of 1 Inflation-indexed Derivatives inflation derivatives with Barclays Capital, in which it received a floating-rate, inflation-linked interest rate and paid nominal fixed- rate interest rate. The swaps ranged in maturity from 18 to 28 years, with a total notional amount of £300 million. -

Total Return Swap • Exchange the Total Economic Performance of a Specific Asset for Another Cash Flow

Total return swap • Exchange the total economic performance of a specific asset for another cash flow. total return of asset Total return Total return payer receiver LIBOR + Y bp Total return comprises the sum of interests, fees and any change-in-value payments with respect to the reference asset. A commercial bank can hedge all credit risk on a loan it has originated. The counterparty can gain access to the loan on an off-balance sheet basis, without bearing the cost of originating, buying and administering the loan. 1 The payments received by the total return receiver are: 1. The coupon c of the bond (if there were one since the last payment date Ti − 1) + 2. The price appreciation ( C ( T i ) − C ( T i − 1 ) ) of the underlying bond C since the last payment (if there were only). 3. The recovery value of the bond (if there were default). The payments made by the total return receiver are: 1. A regular fee of LIBOR + sTRS + 2. The price depreciation ( C ( T i − 1 ) − C ( T i ) ) of bond C since the last payment (if there were only). 3. The par value of the bond C if there were a default in the meantime). The coupon payments are netted and swap’s termination date is earlier than bond’s maturity. 2 Some essential features 1. The receiver is synthetically long the reference asset without having to fund the investment up front. He has almost the same payoff stream as if he had invested in risky bond directly and funded this investment at LIBOR + sTRS. -

Credit Derivatives

3 Credit Derivatives CHAPTER 7 Credit derivatives Collaterized debt obligation Credit default swap Credit spread options Credit linked notes Risks in credit derivatives Credit Derivatives •A credit derivative is a financial instrument whose value is determined by the default risk of the principal asset. •Financial assets like forward, options and swaps form a part of Credit derivatives •Borrowers can default and the lender will need protection against such default and in reality, a credit derivative is a way to insure such losses Credit Derivatives •Credit default swaps (CDS), total return swap, credit default swap options, collateralized debt obligations (CDO) and credit spread forwards are some examples of credit derivatives •The credit quality of the borrower as well as the third party plays an important role in determining the credit derivative’s value Credit Derivatives •Credit derivatives are fundamentally divided into two categories: funded credit derivatives and unfunded credit derivatives. •There is a contract between both the parties stating the responsibility of each party with regard to its payment without resorting to any asset class Credit Derivatives •The level of risk differs in different cases depending on the third party and a fee is decided based on the appropriate risk level by both the parties. •Financial assets like forward, options and swaps form a part of Credit derivatives •The price for these instruments changes with change in the credit risk of agents such as investors and government Credit derivatives Collaterized debt obligation Credit default swap Credit spread options Credit linked notes Risks in credit derivatives Collaterized Debt obligation •CDOs or Collateralized Debt Obligation are financial instruments that banks and other financial institutions use to repackage individual loans into a product sold to investors on the secondary market. -

The Role of Interest Rate Swaps in Corporate Finance

The Role of Interest Rate Swaps in Corporate Finance Anatoli Kuprianov n interest rate swap is a contractual agreement between two parties to exchange a series of interest rate payments without exchanging the A underlying debt. The interest rate swap represents one example of a general category of financial instruments known as derivative instruments. In the most general terms, a derivative instrument is an agreement whose value derives from some underlying market return, market price, or price index. The rapid growth of the market for swaps and other derivatives in re- cent years has spurred considerable controversy over the economic rationale for these instruments. Many observers have expressed alarm over the growth and size of the market, arguing that interest rate swaps and other derivative instruments threaten the stability of financial markets. Recently, such fears have led both legislators and bank regulators to consider measures to curb the growth of the market. Several legislators have begun to promote initiatives to create an entirely new regulatory agency to supervise derivatives trading activity. Underlying these initiatives is the premise that derivative instruments increase aggregate risk in the economy, either by encouraging speculation or by burdening firms with risks that management does not understand fully and is incapable of controlling.1 To be certain, much of this criticism is aimed at many of the more exotic derivative instruments that have begun to appear recently. Nevertheless, it is difficult, if not impossible, to appreciate the economic role of these more exotic instruments without an understanding of the role of the interest rate swap, the most basic of the new generation of financial derivatives.