Hedge Fund Investment Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Synthetic Collateralised Debt Obligation: Analysing the Super-Senior Swap Element

The Synthetic Collateralised Debt Obligation: analysing the Super-Senior Swap element Nicoletta Baldini * July 2003 Basic Facts In a typical cash flow securitization a SPV (Special Purpose Vehicle) transfers interest income and principal repayments from a portfolio of risky assets, the so called asset pool, to a prioritized set of tranches. The level of credit exposure of every single tranche depends upon its level of subordination: so, the junior tranche will be the first to bear the effect of a credit deterioration of the asset pool, and senior tranches the last. The asset pool can be made up by either any type of debt instrument, mainly bonds or bank loans, or Credit Default Swaps (CDS) in which the SPV sells protection1. When the asset pool is made up solely of CDS contracts we talk of ‘synthetic’ Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDOs); in the so called ‘semi-synthetic’ CDOs, instead, the asset pool is made up by both debt instruments and CDS contracts. The tranches backed by the asset pool can be funded or not, depending upon the fact that the final investor purchases a true debt instrument (note) or a mere synthetic credit exposure. Generally, when the asset pool is constituted by debt instruments, the SPV issues notes (usually divided in more tranches) which are sold to the final investor; in synthetic CDOs, instead, tranches are represented by basket CDSs with which the final investor sells protection to the SPV. In any case all the tranches can be interpreted as percentile basket credit derivatives and their degree of subordination determines the percentiles of the asset pool loss distribution concerning them It is not unusual to find both funded and unfunded tranches within the same securitisation: this is the case for synthetic CDOs (but the same could occur with semi-synthetic CDOs) in which notes are issued and the raised cash is invested in risk free bonds that serve as collateral. -

Understanding the Z-Spread Moorad Choudhry*

Learning Curve September 2005 Understanding the Z-Spread Moorad Choudhry* © YieldCurve.com 2005 A key measure of relative value of a corporate bond is its swap spread. This is the basis point spread over the interest-rate swap curve, and is a measure of the credit risk of the bond. In its simplest form, the swap spread can be measured as the difference between the yield-to-maturity of the bond and the interest rate given by a straight-line interpolation of the swap curve. In practice traders use the asset-swap spread and the Z- spread as the main measures of relative value. The government bond spread is also considered. We consider the two main spread measures in this paper. Asset-swap spread An asset swap is a package that combines an interest-rate swap with a cash bond, the effect of the combined package being to transform the interest-rate basis of the bond. Typically, a fixed-rate bond will be combined with an interest-rate swap in which the bond holder pays fixed coupon and received floating coupon. The floating-coupon will be a spread over Libor (see Choudhry et al 2001). This spread is the asset-swap spread and is a function of the credit risk of the bond over and above interbank credit risk.1 Asset swaps may be transacted at par or at the bond’s market price, usually par. This means that the asset swap value is made up of the difference between the bond’s market price and par, as well as the difference between the bond coupon and the swap fixed rate. -

Not for Reproduction Not for Reproduction

Structured Products Europe Awards 2011 to 10% for GuardInvest against 39% for a direct Euro Stoxx 50 investment. “The problem is so many people took volatility as a hedging vehicle over There was also €67.21 million invested in the Theam Harewood Euro time that the price of volatility has gone up, and everybody has suffered Long Dividends Funds by professional investors. Spying the relationship losses of 20%, 30%, 40% on the cost of carry,” says Pacini. “When volatility between dividends and inflation – that finds companies traditionally spiked, people sold quickly, preventing volatility from going up on a paying them in line with inflation – and given that dividends are mark-to-market basis.” House of the year negatively correlated with bonds, the bank’s fund recorded an The bank’s expertise in implied volatility combined with its skills in annualised return of 18.98% by August 31, 2011, against the 1.92% on structured products has allowed it to mix its core long forward variance offer from a more volatile investment in the Euro Stoxx 50. position with a short forward volatility position. The resulting product is BNP Paribas The fund systematically invests in dividend swaps of differing net long volatility and convexity, which protects investors from tail maturities on the European benchmark; the swaps are renewed on their events. The use of variance is a hedge against downside risks and respective maturities. There is an override that reduces exposure to the optimises investment and tail-risk protection. > BNP Paribas was prepared for the worst and liabilities, while providing an attractive yield. -

Federal Register/Vol. 84, No. 215/Wednesday, November 6

Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 215 / Wednesday, November 6, 2019 / Notices 59849 respect to this action, see the each participant will speak, and the SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE application for license amendment time allotted for each presentation. COMMISSION dated October 23, 2019. A written summary of the hearing will [Release No. 34–87434; File No. SR– Attorney for licensee: General be compiled, and such summary will be NYSEArca–2019–12] Counsel, Tennessee Valley Authority, made available, upon written request to 400 West Summit Hill Drive, 6A West OPIC’s Corporate Secretary, at the cost Self-Regulatory Organizations; NYSE Tower, Knoxville, TN 37902. of reproduction. Arca, Inc.; Notice of Filing of NRC Branch Chief: Undine Shoop. Amendment No. 2 and Order Granting Written summaries of the projects to Accelerated Approval of a Proposed Dated at Rockville, Maryland, this 31st day be presented at the December 11, 2019, of October 2019. Rule Change, as Modified by Board meeting will be posted on OPIC’s Amendment No. 2, To List and Trade For the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. website. Kimberly J. Green, Shares of the iShares Commodity Senior Project Manager, Plant Licensing CONTACT PERSON FOR INFORMATION: Curve Carry Strategy ETF Under NYSE Branch II–2, Division of Operating Reactor Information on the hearing may be Arca Rule 8.600–E obtained from Catherine F. I. Andrade at Licensing, Office of Nuclear Reactor I. Introduction Regulation. (202) 336–8768, via facsimile at (202) [FR Doc. 2019–24198 Filed 11–5–19; 8:45 am] 408–0297, or via email at On March 1, 2019, NYSE Arca, Inc. -

Asset Swaps and Credit Derivatives

PRODUCT SUMMARY A SSET S WAPS Creating Synthetic Instruments Prepared by The Financial Markets Unit Supervision and Regulation PRODUCT SUMMARY A SSET S WAPS Creating Synthetic Instruments Joseph Cilia Financial Markets Unit August 1996 PRODUCT SUMMARIES Product summaries are produced by the Financial Markets Unit of the Supervision and Regulation Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago. Product summaries are pub- lished periodically as events warrant and are intended to further examiner understanding of the functions and risks of various financial markets products relevant to the banking industry. While not fully exhaustive of all the issues involved, the summaries provide examiners background infor- mation in a readily accessible form and serve as a foundation for any further research into a par- ticular product or issue. Any opinions expressed are the authors’ alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago or the Federal Reserve System. Should the reader have any questions, comments, criticisms, or suggestions for future Product Summary topics, please feel free to call any of the members of the Financial Markets Unit listed below. FINANCIAL MARKETS UNIT Joseph Cilia(312) 322-2368 Adrian D’Silva(312) 322-5904 TABLE OF CONTENTS Asset Swap Fundamentals . .1 Synthetic Instruments . .1 The Role of Arbitrage . .2 Development of the Asset Swap Market . .2 Asset Swaps and Credit Derivatives . .3 Creating an Asset Swap . .3 Asset Swaps Containing Interest Rate Swaps . .4 Asset Swaps Containing Currency Swaps . .5 Adjustment Asset Swaps . .6 Applied Engineering . .6 Structured Notes . .6 Decomposing Structured Notes . .7 Detailing the Asset Swap . -

Fixed Income 2

2 | Fixed Income Fixed 2 CFA Society Italy CFA Society Italy è l’associazione Italiana dei professionisti che lavorano nell’industria Fixed finanziaria italiana. CFA Society Italy nata nel 1999 come organizzazione no profit, è affiliata a CFA Institute, l’associazione globale di professionisti degli investimenti che definisce gli Income standard di eccellenza per il settore. CFA Society Italy ha attualmente oltre 400 soci attivi, nel mondo i professionisti certificati CFA® sono oltre 150.000. Assegnato per la prima volta nel 1963, CFA® è la designazione di eccellenza professionale per la comunità finanziaria internazionale. Il programma CFA® offre una sfida educativa davvero globale in cui è possibile creare una conoscenza fondamentale dei principi di investimento, rilevante per ogni mercato mondiale. I soci che hanno acquisito la certificazione CFA® incarnano le quattro virtù che sono le caratteristiche distintive di CFA Institute: Etica, Tenacia, Rigore e Analisi. CFA Society Italia offre una gamma di opportunità educative e facilita lo scambio aperto di informazioni e opinioni tra professionisti degli investimenti, grazie ad una serie continua di eventi per i propri membri. I nostri soci hanno la possibilità di entrare in contatto con la comunità finanziaria italiana aumentando il proprio network lavorativo. I membri di CFA Society Italy hanno inoltre la posibilità di partecipare attivamente ad iniziative dell’associazione, che Guida a cura di Con la collaborazione di consentono di fare leva sulle proprie esperienze lavorative. L’iscrizione e il completamento degli esami del programma CFA®, anche se fortemente raccomandati, non sono un requisito per l’adesione e incoraggiamo attivamente i professionisti italiani del settore finanziario a unirsi alla nostra associazione. -

Total Return Swap • Exchange the Total Economic Performance of a Specific Asset for Another Cash Flow

Total return swap • Exchange the total economic performance of a specific asset for another cash flow. total return of asset Total return Total return payer receiver LIBOR + Y bp Total return comprises the sum of interests, fees and any change-in-value payments with respect to the reference asset. A commercial bank can hedge all credit risk on a loan it has originated. The counterparty can gain access to the loan on an off-balance sheet basis, without bearing the cost of originating, buying and administering the loan. 1 The payments received by the total return receiver are: 1. The coupon c of the bond (if there were one since the last payment date Ti − 1) + 2. The price appreciation ( C ( T i ) − C ( T i − 1 ) ) of the underlying bond C since the last payment (if there were only). 3. The recovery value of the bond (if there were default). The payments made by the total return receiver are: 1. A regular fee of LIBOR + sTRS + 2. The price depreciation ( C ( T i − 1 ) − C ( T i ) ) of bond C since the last payment (if there were only). 3. The par value of the bond C if there were a default in the meantime). The coupon payments are netted and swap’s termination date is earlier than bond’s maturity. 2 Some essential features 1. The receiver is synthetically long the reference asset without having to fund the investment up front. He has almost the same payoff stream as if he had invested in risky bond directly and funded this investment at LIBOR + sTRS. -

Credit Derivatives

3 Credit Derivatives CHAPTER 7 Credit derivatives Collaterized debt obligation Credit default swap Credit spread options Credit linked notes Risks in credit derivatives Credit Derivatives •A credit derivative is a financial instrument whose value is determined by the default risk of the principal asset. •Financial assets like forward, options and swaps form a part of Credit derivatives •Borrowers can default and the lender will need protection against such default and in reality, a credit derivative is a way to insure such losses Credit Derivatives •Credit default swaps (CDS), total return swap, credit default swap options, collateralized debt obligations (CDO) and credit spread forwards are some examples of credit derivatives •The credit quality of the borrower as well as the third party plays an important role in determining the credit derivative’s value Credit Derivatives •Credit derivatives are fundamentally divided into two categories: funded credit derivatives and unfunded credit derivatives. •There is a contract between both the parties stating the responsibility of each party with regard to its payment without resorting to any asset class Credit Derivatives •The level of risk differs in different cases depending on the third party and a fee is decided based on the appropriate risk level by both the parties. •Financial assets like forward, options and swaps form a part of Credit derivatives •The price for these instruments changes with change in the credit risk of agents such as investors and government Credit derivatives Collaterized debt obligation Credit default swap Credit spread options Credit linked notes Risks in credit derivatives Collaterized Debt obligation •CDOs or Collateralized Debt Obligation are financial instruments that banks and other financial institutions use to repackage individual loans into a product sold to investors on the secondary market. -

Introduction Section 4000.1

Introduction Section 4000.1 This section contains product profiles of finan- Each product profile contains a general cial instruments that examiners may encounter description of the product, its basic character- during the course of their review of capital- istics and features, a depiction of the market- markets and trading activities. Knowledge of place, market transparency, and the product’s specific financial instruments is essential for uses. The profiles also discuss pricing conven- examiners’ successful review of these activities. tions, hedging issues, risks, accounting, risk- These product profiles are intended as a general based capital treatments, and legal limitations. reference for examiners; they are not intended to Finally, each profile contains references for be independently comprehensive but are struc- more information. tured to give a basic overview of the instruments. Trading and Capital-Markets Activities Manual February 1998 Page 1 Federal Funds Section 4005.1 GENERAL DESCRIPTION commonly used to transfer funds between depository institutions: Federal funds (fed funds) are reserves held in a bank’s Federal Reserve Bank account. If a bank • The selling institution authorizes its district holds more fed funds than is required to cover Federal Reserve Bank to debit its reserve its Regulation D reserve requirement, those account and credit the reserve account of the excess reserves may be lent to another financial buying institution. Fedwire, the Federal institution with an account at a Federal Reserve Reserve’s electronic funds and securities trans- Bank. To the borrowing institution, these funds fer network, is used to complete the transfer are fed funds purchased. To the lending institu- with immediate settlement. -

Commodity Index Traders and the Boom/Bust Cycle in Commodities Prices

Page 2 Commodity Index Traders and the Boom/Bust Cycle in Commodities Prices David Frenk and Wallace Turbeville* ©Better Markets 2011 ABSTRACT Since 2005, the public has lived with high and volatile prices for basic energy and agricultural commodities. The public focus on this unprecedented commodity price volatility has been intense, because a large proportion of the cost of living borne by individuals and families in the U.S. (and around the globe) is represented by commodities- based costs, notably food, fuel, and clothing. Interestingly, as commodity prices have shown more price volatility, there has been an accompanying significant increase in the volume of commodities futures and swaps transactions, as well as commodities markets open interest. Moreover, Commodity Index Traders (“CITs”), a relatively new type of participant, now collectively make up the single largest group of non-commercial participants in commodities futures markets. These CITs, which represent giant institutional pools of capital, have at times been the single largest class of participant, outweighing bona fide hedgers (producers and consumers of commodities) and traditional “speculators,” who take short-term bi-directional bets and provide liquidity. Given both the size and the specific and largely homogeneous investment strategy of the CITs, many market observers have concluded that this group is most likely responsible for greatly disrupting price formation in commodities futures markets. Further, it has been posited that this distortion has directly led to -

Consolidated Policy on Valuation Adjustments Global Capital Markets

Global Consolidated Policy on Valuation Adjustments Consolidated Policy on Valuation Adjustments Global Capital Markets September 2008 Version Number 2.35 Dilan Abeyratne, Emilie Pons, William Lee, Scott Goswami, Jerry Shi Author(s) Release Date September lOth 2008 Page 1 of98 CONFIDENTIAL TREATMENT REQUESTED BY BARCLAYS LBEX-BARFID 0011765 Global Consolidated Policy on Valuation Adjustments Version Control ............................................................................................................................. 9 4.10.4 Updated Bid-Offer Delta: ABS Credit SpreadDelta................................................................ lO Commodities for YH. Bid offer delta and vega .................................................................................. 10 Updated Muni section ........................................................................................................................... 10 Updated Section 13 ............................................................................................................................... 10 Deleted Section 20 ................................................................................................................................ 10 Added EMG Bid offer and updated London rates for all traded migrated out oflens ....................... 10 Europe Rates update ............................................................................................................................. 10 Europe Rates update continue ............................................................................................................. -

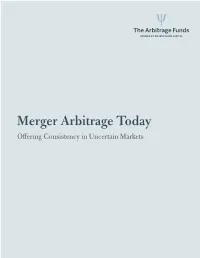

Merger Arbitrage Today Offering Consistency in Uncertain Markets a Differentiated Return Stream

Ψ The Arbitrage Funds advised by water island capital Merger Arbitrage Today Offering Consistency in Uncertain Markets A Differentiated Return Stream In Times of Equity Market Stress Merger Arbitrage is a time-tested strategy that has historically provided returns 100% uncorrelated to broader swings in the market. During times of market stress, the Percentage of time strategy may provide an important source of diversification for an investor’s portfolio. Merger Arbitrage outperformed Stocks average return average return in months Stocks in months stocks are down in years stocks are down were down. 5% 3.29% Source: Morningstar; Date range: 1/1/10-12/31/19. 0% -0.25% -3.28% -5% -4.38% Merger Arbitrage Stocks Source: Morningstar. Date Range: 1/1/10-12/31/19. Past performance does not guarantee future results. “Merger Arbitrage” represented by HFRI Merger Arbitrage. “Stocks” represented by S&P 500. Index returns are for illustrative purposes only and do not represent actual performance. S&P 500 returns do not reflect any management fees, transaction costs, or expenses. Indices are unmanaged and one cannot invest directly in an index. Greater Levels of Volatility Because returns are closely tied to the outcome of specific, short-term events, rather -21% than overall market direction, volatility can offer attractive entry points. It can also lead to the re-pricing of risk, allowing for greater return potential. Merger Arbitrage VIX five-year average relative to its historic performance has historically been better than Stocks when market volatility increases. average. sum of daily returns on days when the vix is above or below its average level VIX Avg/Historical Avg 120% 108% -20% 2019 100% -13% 2018 80% 40% -42% 2017 20% 8% 5% -17% 2016 0% -13% 2015 -20% -40% Source: CBOE; Water Island Capital.