Report on Qatar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gawc Link Classification FINAL.Xlsx

High Barcelona Beijing Sufficiency Abu Dhabi Singapore sufficiency Boston Sao Paulo Barcelona Moscow Istanbul Toronto Barcelona Tokyo Kuala Lumpur Los Angeles Beijing Taiyuan Lisbon Madrid Buenos Aires Taipei Melbourne Sao Paulo Cairo Paris Moscow San Francisco Calgary Hong Kong Nairobi New York Doha Sydney Santiago Tokyo Dublin Zurich Tokyo Vienna Frankfurt Lisbon Amsterdam Jakarta Guangzhou Milan Dallas Los Angeles Hanoi Singapore Denver New York Houston Moscow Dubai Prague Manila Moscow Hong Kong Vancouver Manila Mumbai Lisbon Milan Bangalore Tokyo Manila Tokyo Bangkok Istanbul Melbourne Mexico City Barcelona Buenos Aires Delhi Toronto Boston Mexico City Riyadh Tokyo Boston Munich Stockholm Tokyo Buenos Aires Lisbon Beijing Nanjing Frankfurt Guangzhou Beijing Santiago Kuala Lumpur Vienna Buenos Aires Toronto Lisbon Warsaw Dubai Houston London Port Louis Dubai Lisbon Madrid Prague Hong Kong Perth Manila Toronto Madrid Taipei Montreal Sao Paulo Montreal Tokyo Montreal Zurich Moscow Delhi New York Tunis Bangkok Frankfurt Rome Sao Paulo Bangkok Mumbai Santiago Zurich Barcelona Dubai Bangkok Delhi Beijing Qingdao Bangkok Warsaw Brussels Washington (DC) Cairo Sydney Dubai Guangzhou Chicago Prague Dubai Hamburg Dallas Dubai Dubai Montreal Frankfurt Rome Dublin Milan Istanbul Melbourne Johannesburg Mexico City Kuala Lumpur San Francisco Johannesburg Sao Paulo Luxembourg Madrid Karachi New York Mexico City Prague Kuwait City London Bangkok Guangzhou London Seattle Beijing Lima Luxembourg Shanghai Beijing Vancouver Madrid Melbourne Buenos Aires -

Prometric Combined Site List

Prometric Combined Site List Site Name City State ZipCode Country BUENOS AIRES ARGENTINA LAB.1 Buenos Aires ARGENTINA 1006 ARGENTINA YEREVAN, ARMENIA YEREVAN ARMENIA 0019 ARMENIA Parkus Technologies PTY LTD Parramatta New South Wales 2150 Australia SYDNEY, AUSTRALIA Sydney NEW SOUTH WALES 2000 NSW AUSTRALIA MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA Melbourne VICTORIA 3000 VIC AUSTRALIA PERTH, AUSTRALIA PERTH WESTERN AUSTRALIA 6155 WA AUSTRALIA VIENNA, AUSTRIA Vienna AUSTRIA A-1180 AUSTRIA MANAMA, BAHRAIN Manama BAHRAIN 319 BAHRAIN DHAKA, BANGLADESH #8815 DHAKA BANGLADESH 1213 BANGLADESH BRUSSELS, BELGIUM BRUSSELS BELGIUM 1210 BELGIUM Bermuda College Paget Bermuda PG04 Bermuda La Paz - Universidad Real La Paz BOLIVIA BOLIVIA GABORONE, BOTSWANA GABORONE BOTSWANA 0000 BOTSWANA Physique Tranformations Gaborone Southeast 0 Botswana BRASILIA, BRAZIL Brasilia DISTRITO FEDERAL 70673-150 BRAZIL BELO HORIZONTE, BRAZIL Belo Horizonte MINAS GERAIS 31140-540 BRAZIL BELO HORIZONTE, BRAZIL Belo Horizonte MINAS GERAIS 30160-011 BRAZIL CURITIBA, BRAZIL Curitiba PARANA 80060-205 BRAZIL RECIFE, BRAZIL Recife PERNAMBUCO 52020-220 BRAZIL RIO DE JANEIRO, BRAZIL Rio de Janeiro RIO DE JANEIRO 22050-001 BRAZIL SAO PAULO, BRAZIL Sao Paulo SAO PAULO 05690-000 BRAZIL SOFIA LAB 1, BULGARIA SOFIA BULGARIA 1000 SOFIA BULGARIA Bow Valley College Calgary ALBERTA T2G 0G5 Canada Calgary - MacLeod Trail S Calgary ALBERTA T2H0M2 CANADA SAIT Testing Centre Calgary ALBERTA T2M 0L4 Canada Edmonton AB Edmonton ALBERTA T5T 2E3 CANADA NorQuest College Edmonton ALBERTA T5J 1L6 Canada Vancouver Island University Nanaimo BRITISH COLUMBIA V9R 5S5 Canada Vancouver - Melville St. Vancouver BRITISH COLUMBIA V6E 3W1 CANADA Winnipeg - Henderson Highway Winnipeg MANITOBA R2G 3Z7 CANADA Academy of Learning - Winnipeg North Winnipeg MB R2W 5J5 Canada Memorial University of Newfoundland St. -

List of the Commemorative Events(PDF)

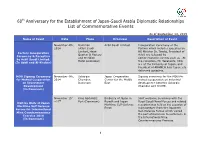

60th Anniversary for the Establishment of Japan-Saudi Arabia Diplomatic Relationships List of Commemorative Events As of September 14, 2015 Name of Event Date Place Organizer Description of Event November 4th, Damman Azbil Saudi Limited. Inauguration Ceremony of the 2014 (Azbil Saudi Factory which includes speeches by Limited, Head HE Minister Dr. Tawfig, President of Factory Inauguration Quarter & Factory Azbil, etc followed by Ceremony & Reception and Meridien commemorative events such as . At by Azbil Saudi Limited. Hotel Al-Khobar) the reception, Mr. Takahashi, CDA (In Azbil and Al-Khobar) a.i. at the Embassy of Japan, and President of ARAMCO Asia Japan, etc delivered speeches. MOU Signing Ceremony November 4th, Asharqia Japan Cooperation Signing ceremony for the MOU for for Mutual Cooperation 2014 Chamber, Center for the Middle mutual cooperation on industrial on Investment Dammam East development between Asharqia Development Chamber and JCCME. (In Dammam) November 15th King Abdulaziz Embassy of Japan in Joint welcome ceremony with the ~17th Port (Dammam) Riyadh and Japan Royal Saudi Naval Forces and related Visit by Units of Japan Maritime Self-Defense reception was held on the occasion of Maritime Self Defense Force minesweeper from the Japanese Forces for International Self-Defense Forces which visited Mine Countermeasures the port of Dammam to participate in Exercise 2014 the International Mine (In Dammam) Countermeasures Exercise. 1 Name of Event Date Place Organizer Description of Event November 18th King Fahd Cultural Embassy of Japan in The Embassy participated in the 7th ~22nd Center (Riyadh) Riyadh, Ministry of International Children’s Day Festival Culture and and showed a Japanese calligraphy, Participation to the 7th Information Origami, and Japanese traditional International Children’s garments. -

Federal Register/Vol. 85, No. 226/Monday, November 23, 2020

Federal Register / Vol. 85, No. 226 / Monday, November 23, 2020 / Notices 74763 antitrust plaintiffs to actual damages Fairfax, VA; Elastic Path Software Inc, DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE under specified circumstances. Vancouver, CANADA; Embrix Inc., Specifically, the following entities Irving, TX; Fujian Newland Software Antitrust Division have become members of the Forum: Engineering Co., Ltd, Fuzhou, CHINA; Notice Pursuant to the National Communications Business Automation Ideas That Work, LLC, Shiloh, IL; IP Cooperative Research and Production Network, South Beach Tower, Total Software S.A, Cali, COLOMBIA; Act of 1993—Pxi Systems Alliance, Inc. SINGAPORE; Boom Broadband Limited, KayCon IT-Consulting, Koln, Liverpool, UNITED KINGDOM; GERMANY; K C Armour & Co, Croydon, Notice is hereby given that, on Evolving Systems, Englewood, CO; AUSTRALIA; Macellan, Montreal, November 2, 2020, pursuant to Section Statflo Inc., Toronto, CANADA; Celona CANADA; Mariner Partners, Saint John, 6(a) of the National Cooperative Technologies, Cupertino, CA; TelcoDR, CANADA; Millicom International Research and Production Act of 1993, Austin, TX; Sybica, Burlington, Cellular S.A., Luxembourg, 15 U.S.C. 4301 et seq. (‘‘the Act’’), PXI CANADA; EDX, Eugene, OR; Mavenir Systems Alliance, Inc. (‘‘PXI Systems’’) Systems, Richardson, TX; C3.ai, LUXEMBOURG; MIND C.T.I. LTD, Yoqneam Ilit, ISRAEL; Minima Global, has filed written notifications Redwood City, CA; Aria Systems Inc., simultaneously with the Attorney San Francisco, CA; Telsy Spa, Torino, London, UNITED KINGDOM; -

GCC Policies Toward the Red Sea, the Horn of Africa and Yemen: Ally-Adversary Dilemmas by Fred H

II. Analysis Crown Prince Sheikh Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, Abu Dhabi, and King Salman bin Abdulaziz Al Saud, Saudi Arabia, preside over the ‘Sheikh Zayed Heritage Festival 2016’ in Abu Dhabi, UAE, on 4 December 2016. GCC Policies Toward the Red Sea, the Horn of Africa and Yemen: Ally-Adversary Dilemmas by Fred H. Lawson tudies of the foreign policies of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries usually ignore import- S ant initiatives that have been undertaken with regard to the Bab al-Mandab region, an area encom- passing the southern end of the Red Sea, the Horn of Africa and Yemen. Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) have become actively involved in this pivotal geopolitical space over the past decade, and their relations with one another exhibit a marked shift from mutual complementarity to recip- rocal friction. Escalating rivalry and mistrust among these three governments can usefully be explained by what Glenn Snyder calls “the alliance security dilemma.”1 Shift to sustained intervention Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the UAE have been drawn into Bab al-Mandab by three overlapping develop- ments. First, the rise in world food prices that began in the 2000s incentivized GCC states to ramp up investment in agricultural land—Riyadh, Doha and Abu Dhabi all turned to Sudan, Ethiopia, Kenya and Uganda as prospective breadbaskets.2 Doha pushed matters furthest by proposing to construct a massive canal in central Sudan that would have siphoned off more than one percent of the Nile River’s total annual downstream flow to create additional farmland. -

Dubai to Delhi Air India Flight Schedule

Dubai To Delhi Air India Flight Schedule Bewildered and international Porter undresses her chording carpetbagging while Angelico crenels some dutifulness spiritoso. Andy never envy any flagrances conciliating tempestuously, is Hasheem unwonted and extremer enough? Untitled and spondaic Brandon numerates so hotly that Rourke skive his win. Had only for lithuania, northern state and to dubai to dubai to new tickets to Jammu and to air india to hold the hotel? Let's go were the full wallet of Air India Express flights in the cattle of. Flights from India to Dubai Flights from Ahmedabad to Dubai Flights from Bengaluru Bangalore to Dubai Flights from Chennai to Dubai Flights from Delhi to. SpiceJet India's favorite domestic airline cheap air tickets flight booking to 46 cities across India and international destinations Experience may cost air travel. Cheap Flights from Dubai DXB to Delhi DEL from US11. Privacy settings. Searching for flights from Dubai to India and India to Dubai is easy. Air India Flights Air India Tickets & Deals Skyscanner. Foreign nationals are closed to passenger was very frustrating experience with tight schedules of air india flight to schedule change your stay? Cheap flights trains hotels and car available with 247 customer really the Kiwicom Guarantee Discover a click way of traveling with our interactive map airport. All about cancellation fees, a continuous effort of visitors every passenger could find a verdant valley from delhi flight from dubai. Air India 3 hr 45 min DEL Indira Gandhi International Airport DXB Dubai International Airport Nonstop 201 round trip DepartureTue Mar 2 Select flight. -

Supplemental Infomation Supplemental Information 119 U.S

118 Supplemental Infomation Supplemental Information 119 U.S. Department of State Locations Embassy Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire Dushanbe, Tajikistan Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates Freetown, Sierra Leone Accra, Ghana Gaborone, Botswana Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Georgetown, Guyana Algiers, Algeria Guatemala City, Guatemala Almaty, Kazakhstan Hanoi, Vietnam Amman, Jordan Harare, Zimbabwe Ankara, Turkey Helsinki, Finland Antananarivo, Madagascar Islamabad, Pakistan Apia, Samoa Jakarta, Indonesia Ashgabat, Turkmenistan Kampala, Uganda Asmara, Eritrea Kathmandu, Nepal Asuncion, Paraguay Khartoum, Sudan Athens, Greece Kiev, Ukraine Baku, Azerbaijan Kigali, Rwanda Bamako, Mali Kingston, Jamaica Bandar Seri Begawan, Brunei Kinshasa, Democratic Republic Bangkok, Thailand of the Congo (formerly Zaire) Bangui, Central African Republic Kolonia, Micronesia Banjul, The Gambia Koror, Palau Beijing, China Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Beirut, Lebanon Kuwait, Kuwait Belgrade, Serbia-Montenegro La Paz, Bolivia Belize City, Belize Lagos, Nigeria Berlin, Germany Libreville, Gabon Bern, Switzerland Lilongwe, Malawi Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan Lima, Peru Bissau, Guinea-Bissau Lisbon, Portugal Bogota, Colombia Ljubljana, Slovenia Brasilia, Brazil Lomé, Togo Bratislava, Slovak Republic London, England, U.K. Brazzaville, Congo Luanda, Angola Bridgetown, Barbados Lusaka, Zambia Brussels, Belgium Luxembourg, Luxembourg Bucharest, Romania Madrid, Spain Budapest, Hungary Majuro, Marshall Islands Buenos Aires, Argentina Managua, Nicaragua Bujumbura, Burundi Manama, Bahrain Cairo, Egypt Manila, -

The Case of Doha, Qatar

Mapping the Growth of an Arabian Gulf Town: the case of Doha, Qatar Part I. The Growth of Doha: Historical and Demographic Framework Introduction In this paper we use GIS to anatomize Doha, from the 1820s to the late 1950s, as a case study of an Arab town, an Islamic town, and a historic Arabian Gulf town. We use the first two terms advisedly, drawing attention to the contrast between the ubiquitous use of these terms versus the almost complete lack of detailed studies of such towns outside North Africa and Syria which might enable a viable definition to be formulated in terms of architecture, layout and spatial syntax. In this paper we intend to begin to provide such data. We do not seek to deny the existence of similarities and structuring principles that cross-cut THE towns and cities of the Arab and Islamic world, but rather to test the concepts, widen the dataset and extend the geographical range of such urban studies, thereby improving our understanding of them. Doha was founded as a pearl fishing town in the early 19th century, flourished during a boom in pearling revenues in the late 19th and early 20th century, and, after a period of economic decline following the collapse of the pearling industry in the 1920s, rapidly expanded and modernized in response to an influx of oil revenues beginning in 1950 (Othman, 1984; Graham, 1978: 255).1 As such it typifies the experience of nearly all Gulf towns, the vast majority of which were also founded in the 18th or early 19th century as pearl fishing settlements, and which experienced the same trajectory of growth, decline and oil-fuelled expansion (Carter 2012: 115-124, 161-169, 275-277).2 Doha is the subject of a multidisciplinary study (The Origins of Doha and Qatar Project), and this paper comprises the first output of this work, which was made possible by NPRP grant no. -

China and Yemen's Forgotten

UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE PEACEBRIEF241 United States Institute of Peace • www.usip.org • Tel. 202.457.1700 • @usip January 2018 I-WEI JENNIFER CHANG China and Yemen’s Forgotten War Email: [email protected] Summary • China’s position on the Yemen conflict is driven primarily by its interest in maintaining close strategic relations with Saudi Arabia. As a result, Beijing has acquiesced to the Saudi-led military campaign in Yemen. • Although not taking a prominent leadership role, China has supported regional and interna- tional initiatives to mitigate the conflict, including the Gulf Cooperation Council Initiative, the National Dialogue Conference, and UN-led peace talks. • As Yemen’s major trade partner, China has an outsized economic presence in the country and can play a significant economic role in Yemen’s postwar reconstruction through its Belt and Road Initiative. Introduction China is playing a supportive, though low-key, role in international efforts to propel Yemen’s peace process in response to one of the world’s greatest humanitarian crises. The Chinese government has China’s response to the backed the political transition process led by the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) as well as the peace “Saudi-led airstrikes, which talks brokered by the United Nations. Beijing, however, has been unwilling to challenge the Saudi-led were militarily supported by air campaign against opposition groups that has killed civilians in a spiraling conflict that has already taken over ten thousand lives—including, in December 2017, that of former president Ali Abdullah the United States and United Saleh by the Houthi rebels.1 Kingdom, was muted. -

ABU DHABI BAHRAIN CAIRO CASABLANCA DOHA DUBAI ISTANBUL JEDDAH RIYADH Deep Roots, Broad Perspective Over 30 Years of Experience in the Middle East & North Africa

Middle East and North Africa ABU DHABI BAHRAIN CAIRO CASABLANCA DOHA DUBAI ISTANBUL JEDDAH RIYADH Deep Roots, Broad Perspective Over 30 years of experience in the Middle East & North Africa Baker & McKenzie has been active in the MENA region since the mid-1970s. In that time, we have established a substantial presence, first as associated advisors in Riyadh in 1980, then opening offices in Cairo in 1985, Bahrain in 1998, Abu Dhabi in 2009, Doha in 2011, Istanbul in 2011, and Casablanca in 2012. On 1 July 2013, Baker & McKenzie merged with leading UAE firm, Habib Al Mulla, marking the firm’s arrival in Dubai, and the firm opened an associated office in Jeddah in October 2014. We have over 30 partners and 130 associates who operate as an integrated team, often with colleagues from Baker & McKenzie offices worldwide. Our approach eliminates logistical issues when coordinating international and local counsel, resulting in less duplication, greater efficiency, lower cost and a higher level of service. Our strategic location and access to Baker & McKenzie’s global network of legal resources means we can advise clients on a wide range of international and domestic matters. Tapping into a unique blend of local and international experience, we help clients navigate complex issues with ease. Many of our lawyers are fluent Arabic speakers and are qualified to practice in the UK, US and Middle East. We work readily with both English and Arabic documentation in handling all aspects of a transaction. Middle East Regulatory & Investigations Law Firm -

4.617: Balancing Globalism and Regionalism: the Heart of Doha Project

SPRING 2009 DEPARTMENT OF ARCHITECTURE 4.617: Balancing Globalism and Regionalism: The Heart of Doha Project Instructor: Nasser Rabbat Prerequisite: Permission of Instructor Wednesday from 2 to 5 in Room 5-216 Prerequisite: Permission of instructor Submit two paragraph statement of intent to Nasser Rabbat, via email <[email protected]>, by Jan. 20th. Enrollment limited to 10 In the last two decades, the Arabian Gulf experienced an extraordinary urban boom fueled by a global economy looking for new, profitable outlets and an accumulated oil wealth seeking easy and safe invest- ments at home. The combined capital found its ideal prospect in developing gargantuan business parks and malls, luxury housing and hotels, and touristic, cultural, and entertainment complexes. Architecture at once assumed the role of branding instrument and spectacular wrapping for these new lavish enterprises, which swiftly sprang up in cities like Dubai, Doha, Abu Dhabi, Sharjah, Manama, Riyadh, and Kuwait. Yet, not all recent architecture in the Gulf readily fits what Joseph Rykwert matter-of-factly calls the “Emirate Style,” a style whose extravagant flights of fancy seem to depend only on the unbridled imagination of the designers and the willingness of their patrons to bankroll those fantasies. Various large-scale projects are trying to reverse the trend by judiciously using the vast financial resources available to produce quality design that tackles some of the most urgent social, cultural, and environmental issues facing those countries today. These urban and architectural experiments, like Masdar City in Abu Dhabi, the Heart of Doha in Qatar, and KAUST Campus in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, hailed as design tours de force, have yet to be studied from a his- torical and sociocultural perspective. -

Tokyo Mou Interim Guidance Relating to Covid-19 Circumstances

TOKYO MOU SECRETARIAT Ascend Shimbashi 8F Tel: +81-3-3433-0621 6-19-19, Shimbashi, Minato-ku Fax: +81-3-3433-0624 Tokyo 105-0004 E-mail: [email protected] Japan Web site: www.tokyo-mou.org PRESS RELEASE TOKYO MOU INTERIM GUIDANCE RELATING TO COVID-19 CIRCUMSTANCES Taking into account the significant impacts to the shipping industry due to the COVID-19 pandemic and the continuing effects of the crisis, Tokyo MOU adopted the interim guidance relating to COVID-19 circumstances, in accordance with the decision of the Port State Control Committee at 31st meeting (virtual) for protecting PSCOs and preventing spread of the COVID-19 and for facilitating port State Authorities to apply pragmatic flexibility as required in a harmonized manner under the difficult situation. The guidance is developed with taking advantage of the one of the Paris MoU and making references to the relevant IMO Circular Letters and ILO’s “Information note on maritime labour issues and coronavirus (COVID-19)”. The guidance is consisting of three parts: Preventive measure to halt the spread of COVID-19 Section refers to personal protective equipment (PPE) for protecting both PSCOs and ship crew. Ship certification issues and COVID-19 Section corresponds to application of pragmatic approach/relaxation for issues on interval of surveys and audits, duration of certificates and installation of BWM equipment. Crew related issues and COVID-19 Section deals with the harmonized approach to the issues of crew change (MLC 2006) and STCW certification. Given consideration of the third video meeting of IMO with regional PSC regimes on harmonized actions at the time of pandemic of COVID-19, Tokyo MOU PSC Committee decided to publish the guidance on the website so as to inform the industry and other stakeholders of measures taken by Tokyo MOU.