The George Washington University Law School Bulletin 2020–2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

House of Representatives the House Was Not in Session Today

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 107 CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION Vol. 147 WASHINGTON, TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 4, 2001 No. 113 House of Representatives The House was not in session today. Its next meeting will be held on Wednesday, September 5, 2001, at 2 p.m. Senate TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 4, 2001 The Senate met at 10 a.m. and was We express our profound sympathy to RESERVATION OF LEADER TIME called to order by the Honorable HARRY the family of former House of Rep- The PRESIDING OFFICER (Mr. DUR- REID, a Senator from the State of Ne- resentatives Chaplain, James Ford. BIN). Under the previous order, the vada. Comfort and bless them in this time of leadership time is reserved. grief and loss. You are our only Lord f PRAYER and Saviour. The Chaplain, Dr. Lloyd John Amen. MORNING BUSINESS Ogilvie, offered the following prayer: The PRESIDING OFFICER. Under Gracious Father, You are the source f the previous order, there will now be a of strength when we trust You, the period for the transaction of morning source of courage when we ask for Your business not to extend beyond the hour help, the source of hope when we won- PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE of 11 a.m. with Senators permitted to der if we can make a difference, the The Honorable HARRY REID led the speak for up to 10 minutes. Under the source of peace in the stresses and Pledge of Allegiance, as follows: previous order, the time until 10:30 strains of applying truth to the forma- a.m. -

When a Landmark Cannot Serve As a Trademark: Trademark Protection for Building Designs

Washington University Journal of Law & Policy Volume 2 Re-Engineering Patent Law: The Challenge of New Technologies January 2000 When a Landmark Cannot Serve as a Trademark: Trademark Protection for Building Designs Andrew T. Spence Washington University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Andrew T. Spence, When a Landmark Cannot Serve as a Trademark: Trademark Protection for Building Designs, 2 WASH. U. J. L. & POL’Y 517 (2000), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy/vol2/iss1/17 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Journal of Law & Policy by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. When a Landmark Cannot Serve as a Trademark: Trademark Protection for Building Designs in Light of Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum, Inc. v. Gentile Productions Andrew T. Spence* For many years the law has recognized the availability of buildings to serve as trademarks. A federally registered trademark exists for the art deco spire of the Chrysler Building and the neoclassical facade of the New York Stock Exchange.1 In fact, approximately one hundred buildings have federally registered trademarks.2 However, the Sixth Circuit’s decision in Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum, Inc. v. Gentile Productions narrowed the scope of protection that such trademarks enjoy.3 In a 1998 split decision, the court reversed a preliminary injunction in a trademark infringement suit between the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum and Charles Gentile, a professional photographer. -

8. Lo Studio Della Giurisprudenza Negli Stati Uniti

8. Lo studio della Giurisprudenza negli Stati Uniti Programmi di specializzazione post-laurea (Advanced Legal Degrees) Uno degli aspetti peculiari della formazione in giurisprudenza negli States e’ che questa materia si studia solo a livellograduate. Per frequentare un corso di legge negli States uno studente deve gia’essere in possesso di un titolo di laurea di primo livello. I diplomi di laurea in giurisprudenza piu’ comuni negli States sono il Juris Doctor (JD) degree e il Master’s degree in Law(LLM). Il JD e’ il diploma che prelude all’esercizio della professione legale negli Stati Uniti e per questo e’ focalizzato soprattutto sul diritto americano (n.b. Per esercitare la professione legale negli States bisogna prima passare il bar exam e comunque essere in possesso di un visto che autorizzi il lavoro negli States).L’ LLM e’ invece un tipo di diploma che viene generalmente conseguito da chi ha gia’ una formazione legale e vuole specializzarsi in un ramo particolare del diritto come ad esempio International law, comparative law, taxation. A livello di dottorato i due diplomi piu’ importanti sono quelli di Doctor of Jiuridical Science (JSD) e di Doctor of Comparative Law Studies (DCL) che preludono per lo piu’ ad una carriera accademica in senso stretto. Riprendere dal punto: presso alcune law schools sono offerti LLM specifici per etc… Svariate università americane presso le law school conferiscono titoli di studio a livello graduate: Master of Laws (LLM) il più comune, il Master of Comparative Law (MCL), programma di specializzazione in Diritto Comparato. Solo alcune law schoolconsentono di conseguire il massimo titolo di specializzazione in giurisprudenza, il Doctor of Juridical Science (SJD). -

Edgar Filing: APPLE INC - Form 8-K APPLE INC Form 8-K March 01, 2016

Edgar Filing: APPLE INC - Form 8-K APPLE INC Form 8-K March 01, 2016 UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT Pursuant to Section 13 OR 15(d) of The Securities Exchange Act of 1934 February 26, 2016 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported) Apple Inc. (Exact name of Registrant as specified in its charter) California 001-36743 94-2404110 (State or other jurisdiction (Commission (IRS. Employer of incorporation) File Number) Identification No.) 1 Infinite Loop Cupertino, California 95014 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) (408) 996-1010 1 Edgar Filing: APPLE INC - Form 8-K (Registrants telephone number, including area code) Not applicable (Former name or former address, if changed since last report.) Check the appropriate box below if the Form 8-K filing is intended to simultaneously satisfy the filing obligation of the Registrant under any of the following provisions: ¨ Written communications pursuant to Rule 425 under the Securities Act (17 CFR 230.425) ¨ Soliciting material pursuant to Rule 14a-12 under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14a-12) ¨ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 14d-2(b) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.14d-2(b)) ¨ Pre-commencement communications pursuant to Rule 13e-4(c) under the Exchange Act (17 CFR 240.13e-4(c)) 2 Edgar Filing: APPLE INC - Form 8-K Item 5.02Departure of Directors or Certain Officers; Election of Directors; Appointment of Certain Officers; Compensatory Arrangements of Certain Officers. (e) The Board of Directors of Apple Inc. previously adopted, subject to shareholder approval, an amendment and restatement of Apples 2014 Employee Stock Plan (the 2014 Plan). -

LL.B. to J.D. and the Professional Degree in Architecture

85THACSA ANNUAL MEETING ANDTECHNOLOGY (ONFEKtNCE 585 LL.B. to J.D. and the Professional Degree in Architecture JOANNA LOMBARD University of Miami Thirty-four years ago, the American Bar Association (ABA) (I) that the lack of uniformity in nolnenclature was recotrunended that Ainerican law schools offer a single confusing to the public and (2) that the J.D. terminol- unified professional degree, the Juris Doctor. Sixty years of ogy inore accurately described the relevant academic sporadic discussion and debate preceded that reconmenda- accomplishment at approved law schools. The Sec- tion. The Bachelor of Laws (LL.B.) had originated as an tion, therefore, recommended that such schools con- undergraduate prograln which evolved over time to graduate fer the degree of Juris Doctor (J.D.) . on those studies while retaining the bachelor's degree designation. In students who successfully coinplete the prograln recognition of the relatively unifonn acceptancc of the 3- leading to the first professional degree in law year graduate prograln as thc first professional degree in law (decapriles 1967, 54). in thc 1960's, a number of law faculty and administrators By 1967, nearly half the law schools had colnplied with the argued for a national consensus confinning the three-year 1964 ABA resolution: a nulnber of law faculty and admin- graduate prograln and changing the first professional degrce istrators continued the debate(deCapri1es 1967, 54). Within from an LL.B. to the J.D. (Doctor of Law). The debate among the next five years, the J.D. emerged as the single, first law faculty and the process through which change occurred professional degree in law and today the J.D. -

Anecdotal List of Public Interest Judges Compiled by the Harvard

Anecdotal List of Public Interest Judges as of 11/3/17 Compiled by the Harvard Law School Office of Career Services and Office of Public Interest Advising. CONFIDENTIAL - for HLS Applicants Only Type Cir Dist City State Judge Last Judge First Notes Circuit 01 Boston MA Barron David OLC Circuit 01 Concord NH Howard Jeffrey Circuit 01 Portland ME Lipez Kermit Circuit 01 Boston MA Lynch Sandra Worked at Harvard Legal Aid Bureau; started career in legal aid and Circuit 01 Providence RI Thompson O. Rogeree family law Circuit 02 New Haven CT Carney Susan Former Yale and Peace Corps GC Has partnered with Judge Katzmann on immigration representation Circuit 02 New York NY Chin Denny project Circuit 02 New York NY Katzmann Robert Circuit 02 New York NY Livingston Debra AUSA Worked as cooperating attorney with ACLU and New York Civil Circuit 02 New York NY Lynch Gerard Liberties Union Circuit 02 New York NY Parker Barrington Circuit 02 Syracuse NY Pooler Rosemary Circuit 02 New York NY Sack Robert Circuit 02 New York NY Straub Chester Circuit 02 Geneseo NY Wesley Richard Circuit 03 Newark NJ Trump Barry Maryanne Circuit 03 Newark NJ Chagares Michael Circuit 03 Newark NJ Fuentes Julio Circuit 03 Newark NJ Greenaway Joseph Circuit 03 Philadelphia PA Krause Cheryl AUSA Circuit 03 Philadelphia PA McKee Theodore Circuit 03 Philadelphia PA Rendell Marjorie Circuit 03 Philadelphia PA Restrepo Luis Felipe ACLU National Prison Project; Former Federal Public Defender Circuit 03 Scranton PA Vanaskie Thomas Circuit 04 Raleigh NC Duncan Allyson Circuit 04 Richmond -

Master of Laws

APPLYING FOR & FINANCING YOUR LLM MASTER OF LAWS APPLICATION REQUIREMENTS APPLICATION CHECKLIST Admission to the LLM program is highly For applications to be considered, they must include the following: competitive. To be admitted to the program, ALL APPLICANTS INTERNATIONAL APPLICANTS applicants must possess the following: • Application & Application Fee – apply • Applicants with Foreign Credentials - For electronically via LLM.LSAC.ORG, and pay applicants whose native language is not • A Juris Doctor (JD) degree from an ABA-accredited non-refundable application fee of $75 English and who do not posses a degree from law school or an equivalent degree (a Bachelor of Laws • Official Transcripts: all undergraduate and a college or university whose primary language or LL.B.) from a law school outside the United States. graduate level degrees of instruction is English, current TOEFL or IELTS • Official Law School or Equivalent Transcripts scores showing sufficient proficiency in the • For non-lawyers interested in the LLM in Intellectual • For non-lawyer IP professionals: proof of English language is required. The George Mason Property (IP) Law: a Bachelor’s degree and a Master’s minimum of four years professional experience University Scalia Law School Institution code degree in another field, accompanied by a minimum in an IP-related field is 5827. of four years work experience in IP may be accepted in • 500-Word Statement of Purpose • TOEFL: Minimum of 90 in the iBT test lieu of a law degree. IP trainees and Patent Examiners • Resume (100 or above highly preferred) OR (including Bengoshi) with four or more years of • Letters of Recommendation (2 required) • IELTS: Minimum of 6.5 (7.5 or above experience in IP are welcome to apply. -

The Doctrine of Functionality in Design Patent Cases

University of Baltimore Law Review Volume 19 Article 17 Issue 1 Number 1 – 2 — Fall 1989/Winter 1990 1989 The oD ctrine of Functionality in Design Patent Cases Perry J. Saidman SAIDMAN DesignLaw Group, LLC John M. Hintz Rimon, P.C. Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Saidman, Perry J. and Hintz, John M. (1989) "The octrD ine of Functionality in Design Patent Cases," University of Baltimore Law Review: Vol. 19: Iss. 1, Article 17. Available at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/ublr/vol19/iss1/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Baltimore Law Review by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE DOCTRINE OF FUNCTIONALITY IN DESIGN PATENT CASES Perry J. Saidmant John M. Hintztt Although the doctrine of functionality has received much attention in its application in trademark law, I courts and commentators have devoted an inadequate amount of attention to the doctrine as it applies to design pat ents. This Article attempts such an analysis of the functionality doctrine in the design patent context by discussing the origins of the doctrine, review ing the leading cases on the issue, and focusing on the underlying reasons for and purpose of the doctrine. This Article concludes that because courts have interpreted the doctrine in two nominally different ways, there is a danger that courts will indiscriminately apply different standards when determining whether a design is functional or nonfunctional. -

Joint Public Health and Law Programs

JOINT PUBLIC HEALTH AND LAW tuition rate and fees are charged for semesters when no Law School courses are taken, including summer sessions. PROGRAMS Visit the Hirsh Program website (http://publichealth.gwu.edu/ Program Contact: J. Teitelbaum programs/joint-jdllm-mphcertificate/) for additional information. The Milken Institute of School of Public Health (SPH), through its Hirsh Health Law and Policy Program, cooperates with the REQUIREMENTS Law School to offer public health and law students multiple programs that foster an interdisciplinary approach to the study MPH requirements in the joint degree programs of health policy, health law, public health, and health care. The course of study for the standalone MPH degree, in one of Available joint programs include the master of public health several focus areas, (http://publichealth.gwu.edu/node/766/) (http://bulletin.gwu.edu/public-health/#graduatetext) (MPH) consists of 45 credits, including a supervised practicum. In the and juris doctor (https://www.law.gwu.edu/juris-doctor/) (JD); dual degree programs with the Law School, the Milken Institute MPH and master of laws (https://www.law.gwu.edu/master- School of Public Health (GWSPH) accepts 8 Law School credits of-laws/) (LLM); and JD or LLM and SPH certificate in various toward completion of the MPH degree. Therefore, Juris doctor subject areas. LLM students may be enrolled in either the (JD) and master of laws (LLM) students in the dual program general or environmental law program at the Law School. complete only 37 credits of coursework through GWSPH to obtain an MPH degree. Application of credits between programs Depending upon the focus area in which a JD student chooses For the JD/MPH, 8 JD credits are applied toward the MPH and to study, as a rule, the joint degree can be earned in three- up to 12 MPH credits may be applied toward the JD. -

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers

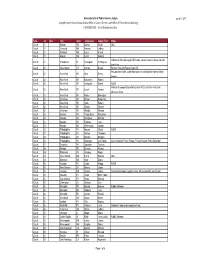

Minority Percentages at Participating Newspapers Asian Native Asian Native Am. Black Hisp Am. Total Am. Black Hisp Am. Total ALABAMA The Anniston Star........................................................3.0 3.0 0.0 0.0 6.1 Free Lance, Hollister ...................................................0.0 0.0 12.5 0.0 12.5 The News-Courier, Athens...........................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Lake County Record-Bee, Lakeport...............................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 The Birmingham News................................................0.7 16.7 0.7 0.0 18.1 The Lompoc Record..................................................20.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 The Decatur Daily........................................................0.0 8.6 0.0 0.0 8.6 Press-Telegram, Long Beach .......................................7.0 4.2 16.9 0.0 28.2 Dothan Eagle..............................................................0.0 4.3 0.0 0.0 4.3 Los Angeles Times......................................................8.5 3.4 6.4 0.2 18.6 Enterprise Ledger........................................................0.0 20.0 0.0 0.0 20.0 Madera Tribune...........................................................0.0 0.0 37.5 0.0 37.5 TimesDaily, Florence...................................................0.0 3.4 0.0 0.0 3.4 Appeal-Democrat, Marysville.......................................4.2 0.0 8.3 0.0 12.5 The Gadsden Times.....................................................0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 Merced Sun-Star.........................................................5.0 -

Juris Doctor Program 1

Juris Doctor Program 1 substantive law, develop legal skills, and learn professional values in JURIS DOCTOR PROGRAM actual practice settings. • The Criminal Prosecution Field Placement Program gives students Law Programs an opportunity to work with prosecutors in Kansas state district The First-Year Curriculum attorneys’ offices as well as the office of the U.S. Attorney. They First-year students take courses that ensure they are well grounded in the participate in nearly all phases of the criminal process, including trial subject matter that lies at the heart of the Anglo-American legal tradition work. and that provide a foundation for upper-level classes and for the practice • In the Elder Law Field Placement Program, students work under the of law. Two aspects of the first-year curriculum — the lawyering course supervision of experienced attorneys representing clients in matters and the small-section program — contribute immeasurably to the process such as income maintenance, access to health care, housing, social of learning the law at KU. security, Medicare/Medicaid, and consumer protection. • The Field Placement Program provides students an opportunity to The lawyering course focuses on the skills and values of the profession. perform legal work under the supervision of a practicing attorney Taught by faculty members with extensive practice experience who at pre-approved governmental agencies and public international meet weekly with students in both a traditional classroom setting and organizations. small groups, the course introduces students to the tools all lawyers use • Students in the Judicial Field Placement Program serve as interns for and helps bring students to an understanding of the legal system and state and federal trial judges in Kansas City, Topeka, and Lawrence. -

Report of the Special Litigation Committee of the Board of Directors

APPLE INC. REPORT OF THE SPECIAL LITIGATION COMMITTEE OF THE BOARD REGARDING DIRECTOR DEFENDANTS AND SETTLEMENT MAY 26, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................... 1 II. APPLE’S ENTRY INTO THE EBOOKS MARKET AND THE TRANSACTIONS THAT GAVE RISE TO THE ANTITRUST JUDGMENT ............... 3 A. Background Of The Ebook Industry ...................................................................... 3 B. Apple’s Negotiations With Publishers ................................................................... 4 C. The Launch Of The iPad And iBookstore ............................................................. 5 III. THE ANTITRUST TRIAL, JUDGMENT AND SETTLEMENT .................................... 7 A. Antitrust Judgment ................................................................................................. 7 B. Monetary Settlement .............................................................................................. 8 C. Appellate Proceedings ........................................................................................... 9 IV. THE DERIVATIVE ACTION .......................................................................................... 9 A. Procedural History ................................................................................................. 9 B. The Individual Defendants ................................................................................... 12 C. The Cause Of Action Against The Director