LL.B. to J.D. and the Professional Degree in Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8. Lo Studio Della Giurisprudenza Negli Stati Uniti

8. Lo studio della Giurisprudenza negli Stati Uniti Programmi di specializzazione post-laurea (Advanced Legal Degrees) Uno degli aspetti peculiari della formazione in giurisprudenza negli States e’ che questa materia si studia solo a livellograduate. Per frequentare un corso di legge negli States uno studente deve gia’essere in possesso di un titolo di laurea di primo livello. I diplomi di laurea in giurisprudenza piu’ comuni negli States sono il Juris Doctor (JD) degree e il Master’s degree in Law(LLM). Il JD e’ il diploma che prelude all’esercizio della professione legale negli Stati Uniti e per questo e’ focalizzato soprattutto sul diritto americano (n.b. Per esercitare la professione legale negli States bisogna prima passare il bar exam e comunque essere in possesso di un visto che autorizzi il lavoro negli States).L’ LLM e’ invece un tipo di diploma che viene generalmente conseguito da chi ha gia’ una formazione legale e vuole specializzarsi in un ramo particolare del diritto come ad esempio International law, comparative law, taxation. A livello di dottorato i due diplomi piu’ importanti sono quelli di Doctor of Jiuridical Science (JSD) e di Doctor of Comparative Law Studies (DCL) che preludono per lo piu’ ad una carriera accademica in senso stretto. Riprendere dal punto: presso alcune law schools sono offerti LLM specifici per etc… Svariate università americane presso le law school conferiscono titoli di studio a livello graduate: Master of Laws (LLM) il più comune, il Master of Comparative Law (MCL), programma di specializzazione in Diritto Comparato. Solo alcune law schoolconsentono di conseguire il massimo titolo di specializzazione in giurisprudenza, il Doctor of Juridical Science (SJD). -

Bachelor of Laws (LLBP) - LLB (2020)

Consult the Handbook on the Web at http://www.usq.edu.au/handbook/current for any updates that may occur during the year. Bachelor of Laws (LLBP) - LLB (2020) Bachelor of Laws (LLBP) - LLB QTAC code (Australian and New Zealand applicants): Toowoomba campus: 904111; External: 904115; Spring®eld campus: 924111; Ipswich campus: 934111 CRICOS code (International applicants): 081714F On-campus Online Start: Semester 1 (February) Semester 1 (February) Semester 2 (July) Semester 2 (July) Semester 3 (November) Campus: Ipswich, Toowoomba - Fees: Commonwealth supported place Commonwealth supported place Domestic full fee paying place Domestic full fee paying place International full fee paying place International full fee paying place Standard duration: 3 years full-time, up to 6 years part-time Program To: Bachelor of Laws (Honours) articulation: Contact us Future Australian and New Future International students Current students Zealand students Ask a question Ask a question Ask a question Freecall (within Australia): 1800 Phone: +61 7 4631 5543 Freecall (within Australia): 1800 269 500 Email: [email protected] 007 252 Phone (from outside Australia): +61 Phone (from outside Australia): +61 7 4631 5315 7 4631 2285 Email: [email protected] Email [email protected] Professional accreditation The Bachelor of Laws has been accredited by the Legal Practitioners Admissions Board, Queensland, and the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Queensland as an approved academic quali®cation under the Supreme Court (Admission) Rules 2004 (Qld). It has also been approved by the Australian Law Schools Standards Committee under the Standards for Australian Law Schools adopted by the Council of Australian Law Deans. -

The Professional Bachelor – Law

The Professional Bachelor – Law National professional and degree programme profile for the Professional Bachelor - Law 2012 Credits The Professional Bachelor - Law National professional and degree programme profile for the Professional Bachelor - Law CROHO: 39205 The Professional Bachelor - Law Publication: July 2012 Adopted by the National Consultative Committee for the professional Bachelors of Laws degree programme (HBO-Rechten), in which the following universities of applied sciences (Hogescholen) participate: • Haagse Hogeschool • Hanzehogeschool Groningen • Hogeschool van Amsterdam • Hogeschool van Arnhem en Nijmegen • Hogeschool Inholland • Hogeschool Leiden • Hogeschool Utrecht • Fontys Hogescholen (Juridische Hogeschool) • Avans Hogeschool (Juridische Hogeschool) • Hogeschool Windesheim • Noordelijke Hogeschool Leeuwarden Drawn up by the working group for updating the national professional and following persons: degree• programmeG.F.J. Hupperetz, profile LL.M. for he (Director Professional of Juridische Bachelor Hogeschool - Law, comprising Avans- the Fontys), chairman of the National Consultative Committee for the professional Bachelors of Laws degree programme • T.J.M. Joxhorst, LL.M. (Team leader Professional Bachelor - Law Hanzehogeschool) • Drs. M. Kok (Educationalist at the Hogeschool van Amsterdam) • E.M.Oudejans, LL.M. (Professional Bachelor of Laws degree programme manager at the Hogeschool van Amsterdam), chairman of the working group • R.A. Plantenga, LL.M. (Team leader for Professional Bachelor - Law at Haagse Hogeschool) -

Master of Laws

APPLYING FOR & FINANCING YOUR LLM MASTER OF LAWS APPLICATION REQUIREMENTS APPLICATION CHECKLIST Admission to the LLM program is highly For applications to be considered, they must include the following: competitive. To be admitted to the program, ALL APPLICANTS INTERNATIONAL APPLICANTS applicants must possess the following: • Application & Application Fee – apply • Applicants with Foreign Credentials - For electronically via LLM.LSAC.ORG, and pay applicants whose native language is not • A Juris Doctor (JD) degree from an ABA-accredited non-refundable application fee of $75 English and who do not posses a degree from law school or an equivalent degree (a Bachelor of Laws • Official Transcripts: all undergraduate and a college or university whose primary language or LL.B.) from a law school outside the United States. graduate level degrees of instruction is English, current TOEFL or IELTS • Official Law School or Equivalent Transcripts scores showing sufficient proficiency in the • For non-lawyers interested in the LLM in Intellectual • For non-lawyer IP professionals: proof of English language is required. The George Mason Property (IP) Law: a Bachelor’s degree and a Master’s minimum of four years professional experience University Scalia Law School Institution code degree in another field, accompanied by a minimum in an IP-related field is 5827. of four years work experience in IP may be accepted in • 500-Word Statement of Purpose • TOEFL: Minimum of 90 in the iBT test lieu of a law degree. IP trainees and Patent Examiners • Resume (100 or above highly preferred) OR (including Bengoshi) with four or more years of • Letters of Recommendation (2 required) • IELTS: Minimum of 6.5 (7.5 or above experience in IP are welcome to apply. -

The Business Professional Doctorate As an Informing Channel: a Survey and Analysis

International Journal of Doctoral Studies Volume 4, 2009 The Business Professional Doctorate as an Informing Channel: A Survey and Analysis T. Grandon Gill Uwe Hoppe University of South Florida University of Osnabrueck Tampa, FL, USA Osnabrueck, Germany [email protected] [email protected] Abstract Although growing in popularity in other countries, the business professional doctorate has yet to gain traction in the U.S. Such programs, intended to offer advanced disciplinary and research training to individuals who later plan to apply that training to employment in industry, are fre- quently seen to be inferior to their academically-focused Ph.D. program counterparts. Further- more, if the sole purpose of a doctorate is to develop individuals focused on producing scholarly research articles, that assessment may well be correct. We argue, however, that such a narrowly focused view of the purpose of doctoral programs is self-defeating; by exclusively focusing on scholarly research and writings, we virtually guarantee that our research will never make it into practice. The paper begins by identifying a variety of types of doctoral programs that exist glob- ally and placing these in a conceptual framework. We then present a detailed case study of the information systems (IS) doctoral programs offered in Osnabrueck, Germany—where as many as 90% of candidates choose careers in industry in preference to academia. Finally, we propose— supported using both conceptual arguments drawn from the study of complex informing and ob- served examples—that the greatest benefit of business professional doctorates may be the crea- tion of enduring informing channels between practice and industry. -

On Professional Degree Requirement for Civil Engineering Practice

Session 2515 ON PROFESSIONAL DEGREE REQUIREMENT FOR CIVIL ENGINEERING PRACTICE James T. P. Yao, Loren D. Lutes Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas I. Introduction In May 1998, ASCE NEWS announced that the Board of Direction “approved a resolution endorsing the master’s degree as the first professional degree for the practice of civil engineering.” The July 1998 ASCE NEWS clarified the earlier article by quoting the definition of the “first professional degree” used by the U.S. Department of Education. It is defined as “a degree that signifies both completion of the academic requirements for beginning practice in a given profession and a level of professional skill beyond that normally required for a bachelor’s degree.” Such a degree is generally required for dentists, physicians, pharmacists, lawyers, theologians, and architects. It is usually based on a total of at least six academic years of work. Arguments that have advanced for considering such a professional degree for civil engineering practice include: • The bachelor’s degree is no longer adequate preparation for civil engineering practice. • This change would improve the professional stature of civil engineers and thus improve the compensation of practitioners. • It would provide a clear distinction between civil engineering graduates and technicians. The same July 1998 article reported that the ASCE Board of Direction is contemplating promotion of a policy being prepared by the Educational Activities Committee. Also, the Board may decide to seek support from such organizations as the Accreditation Board of Engineering and Technology, the National Society of Professional Engineers, and the National Council of Examiners for Engineering and Surveying. -

Bachelor Of: Criminal Justice Laws 55 INTERNSHIPS Completed by UC Law Students in Aotearoa and Overseas in 2019

2022 Law Ture Bachelor of: Criminal Justice Laws 55 INTERNSHIPS completed by UC Law students in Aotearoa and overseas in 2019 Adrienne Paul Lecturer, Māori Land Law Ngā Kai o Roto | Contents Why study at UC? Plan your degree More information 1 Welcome to Law 13 Bachelor of Criminal Justice. BCJ 21 Specialisations and 2 Study Law at UC 14 Bachelor of Laws. LLB career opportunities 4 He ture, he ahurea 15 Certificates 24 Frequently asked questions Law and culture 16 Double degrees 25 Contact us 5 Ground-breaking 17 Graduate and academic leadership postgraduate options 6 A world of possibility 7 Teaching innovation Rainbow Diversity Support 8 Learning with purpose Subject guide 9 Student empowerment 18 Subjects 10 Building resilience 11 Real-world experience UC is proud to partner with Ngāi Tūāhuriri and Ngāi Tahu to uphold the mana and aspirations of 12 A strong foundation mana whenua. Published Mei | May 2021. Information may be out of Front cover: In the design Makaurangi, a fingerprint, date at the time of print. Please check the website. the three elements are representative of Ngā Kete o te Wānanga, the three baskets of knowledge, with the lines The University’s official regulations are at and koru a symbol of mana and mana whenua. This www.canterbury.ac.nz/regulations design originates from traditional whakairo (carving) and kōwhaiwhai designs which can often be seen on the rafters inside wharenui (meeting house). Nau mai ki te Ture. Welcome to Law at UC. Kōkiri mai rā e ngā mana Te Kura Ture | UC School of Law The School is also home to Aotearoa puipuiaki, e ngā reo has over 140 years of experience in New Zealand’s only Bachelor tongarerewa ki Te Whare leading legal research and teaching. -

Juris Doctor Program 1

Juris Doctor Program 1 substantive law, develop legal skills, and learn professional values in JURIS DOCTOR PROGRAM actual practice settings. • The Criminal Prosecution Field Placement Program gives students Law Programs an opportunity to work with prosecutors in Kansas state district The First-Year Curriculum attorneys’ offices as well as the office of the U.S. Attorney. They First-year students take courses that ensure they are well grounded in the participate in nearly all phases of the criminal process, including trial subject matter that lies at the heart of the Anglo-American legal tradition work. and that provide a foundation for upper-level classes and for the practice • In the Elder Law Field Placement Program, students work under the of law. Two aspects of the first-year curriculum — the lawyering course supervision of experienced attorneys representing clients in matters and the small-section program — contribute immeasurably to the process such as income maintenance, access to health care, housing, social of learning the law at KU. security, Medicare/Medicaid, and consumer protection. • The Field Placement Program provides students an opportunity to The lawyering course focuses on the skills and values of the profession. perform legal work under the supervision of a practicing attorney Taught by faculty members with extensive practice experience who at pre-approved governmental agencies and public international meet weekly with students in both a traditional classroom setting and organizations. small groups, the course introduces students to the tools all lawyers use • Students in the Judicial Field Placement Program serve as interns for and helps bring students to an understanding of the legal system and state and federal trial judges in Kansas City, Topeka, and Lawrence. -

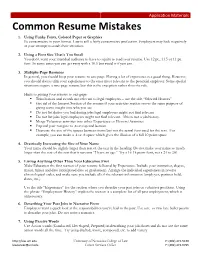

Common Resume Mistakes

Application Materials Common Resume Mistakes 1. Using Funky Fonts, Colored Paper or Graphics Be conservative in your format. Law is still a fairly conservative profession. Employers may look negatively at your attempt to catch their attention. 2. Using a Font Size That’s Too Small You don’t want your intended audience to have to squint to read your resume. Use 12 pt., 11.5 or 11 pt. font. In some cases you can get away with a 10.5 but avoid it if you can. 3. Multiple-Page Resumes In general, you should keep your resume to one page. Having a lot of experience is a good thing. However, you should always trim your experiences to the ones most relevant to the potential employer. Some special situations require a two-page resume but this is the exception rather than the rule. Hints to getting your resume to one page: ! Trim honors and awards not relevant to legal employers – use the title “Selected Honors” ! Get rid of the Interest Section of the resume if your activities section serves the same purpose of giving some insight into who you are ! Do not list duties you had during jobs legal employers might not find relevant ! Do not list jobs legal employers might not find relevant. This is not a job history. ! Merge Volunteer activities into either Experience or Honors/Activities ! Expand your margins to .8 on top and bottom ! Decrease the size of the spaces between items but not the actual font used for the text. For example, you can make a .4 or .6 space which gives the illusion of a full 10 point space 4. -

Classifying Educational Programmes

Classifying Educational Programmes Manual for ISCED-97 Implementation in OECD Countries 1999 Edition ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT Foreword As the structure of educational systems varies widely between countries, a framework to collect and report data on educational programmes with a similar level of educational content is a clear prerequisite for the production of internationally comparable education statistics and indicators. In 1997, a revised International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED-97) was adopted by the UNESCO General Conference. This multi-dimensional framework has the potential to greatly improve the comparability of education statistics – as data collected under this framework will allow for the comparison of educational programmes with similar levels of educational content – and to better reflect complex educational pathways in the OECD indicators. The purpose of Classifying Educational Programmes: Manual for ISCED-97 Implementation in OECD Countries is to give clear guidance to OECD countries on how to implement the ISCED-97 framework in international data collections. First, this manual summarises the rationale for the revised ISCED framework, as well as the defining characteristics of the ISCED-97 levels and cross-classification categories for OECD countries, emphasising the criteria that define the boundaries between educational levels. The methodology for applying ISCED-97 in the national context that is described in this manual has been developed and agreed upon by the OECD/INES Technical Group, a working group on education statistics and indicators representing 29 OECD countries. The OECD Secretariat has also worked closely with both EUROSTAT and UNESCO to ensure that ISCED-97 will be implemented in a uniform manner across all countries. -

*Law 02-03-Book

PROGRAMS of INSTRUCTION THE DOCTOR OF LAW (J.D.) DEGREE The regular curriculum in the Law School is a three-year (nine-quarter) program leading to the degree of Doctor of Law (J.D.). The program is open to candidates who have received a Bachelor’s degree from an approved college before beginning their study in the Law School and to a limited number of highly qualified students who have completed three years of undergraduate studies but have not received degrees. The Law School will not award Bachelor’s degrees to such candidates, but in some cases undergraduate institutions will treat the first year of law study as ful- filling part of the requirements for their own Bachelor’s degrees. The entering class for the J.D. program is limited to approximately 185 students. All students begin the program during the Autumn Quarter in September. The cal- endar for the academic year is located on the last page of these Announcements. THE JOINT DEGREE PROGRAMS Students may apply for joint degrees with other divisions of the University. The stu- dent must gain acceptance to each degree program separately. The following joint degrees are the most popular: Business: Students can earn both the J.D. and the M.B.A. degrees in four calen- dar years. Students may also pursue a J.D./Ph.D. in conjunction with the Graduate School of Business. History: The Law School and the Department of History offer a joint program leading to the J.D. degree and the Ph.D. degree in history. Economics: Law students may use several courses offered in the Law School’s Law and Economics Program to satisfy course requirements in the Department of Econom- ics for the Ph.D. -

282 Part 361—State Vocational Re- Habilitation

Pt. 361 34 CFR Ch. III (7–1–18 Edition) PART 361—STATE VOCATIONAL RE- 361.37 Information and referral programs. 361.38 Protection, use, and release of per- HABILITATION SERVICES PRO- sonal information. GRAM 361.39 State-imposed requirements. 361.40 Reports; Evaluation standards and Subpart A—General performance indicators. Sec. PROVISION AND SCOPE OF SERVICES 361.1 Purpose. 361.41 Processing referrals and applications. 361.2 Eligibility for a grant. 361.3 Authorized activities. 361.42 Assessment for determining eligi- 361.4 Applicable regulations. bility and priority for services. 361.5 Applicable definitions. 361.43 Procedures for ineligibility deter- mination. Subpart B—State Plan and Other Require- 361.44 Closure without eligibility deter- ments for Vocational Rehabilitation mination. 361.45 Development of the individualized Services plan for employment. 361.10 Submission, approval, and dis- 361.46 Content of the individualized plan for approval of the State plan. employment. 361.11 Withholding of funds. 361.47 Record of services. 361.48 Scope of vocational rehabilitation ADMINISTRATION services for individuals with disabilities. 361.12 Methods of administration. 361.49 Scope of vocational rehabilitation 361.13 State agency for administration. services for groups of individuals with 361.14 Substitute State agency. disabilities. 361.15 Local administration. 361.50 Written policies governing the provi- 361.16 Establishment of an independent sion of services for individuals with dis- commission or a State Rehabilitation abilities. Council. 361.51 Standards for facilities and providers 361.17 Requirements for a State Rehabilita- of services. tion Council. 361.52 Informed choice. 361.18 Comprehensive system of personnel 361.53 Comparable services and benefits.