Geopolitical Shifts in West Asia[Initial].P65

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Gulf Takes Charge in the MENA Region

The Gulf takes charge in the MENA region Edward Burke Sara Bazoobandi Working Paper / Documento de trabajo 9797 April 2010 Working Paper / Documento de trabajo About FRIDE FRIDE is an independent think-tank based in Madrid, focused on issues related to democracy and human rights; peace and security; and humanitarian action and development. FRIDE attempts to influence policy-making and inform pub- lic opinion, through its research in these areas. Working Papers FRIDE’s working papers seek to stimulate wider debate on these issues and present policy-relevant considerations. 9 The Gulf takes charge in the MENA1 region Edward Burke and Sara Bazoobandi April 2010 Edward Burke is a researcher at FRIDE. Sara Bazoobandi is a PhD candidate at Exeter University. In 2009 Sara completed a research fellowship at FRIDE. Working Paper / Documento de trabajo 9797 April 2010 Working Paper / Documento de trabajo This Working paper is supported by the European Commission under the Al-Jisr project. Cover photo: Ammar Abd Rabbo/Flickr © Fundación para las Relaciones Internacionales y el Diálogo Exterior (FRIDE) 2010. Goya, 5-7, Pasaje 2º. 28001 Madrid – SPAIN Tel.: +34 912 44 47 40 – Fax: +34 912 44 47 41 Email: [email protected] All FRIDE publications are available at the FRIDE website: www.fride.org This document is the property of FRIDE. If you would like to copy, reprint or in any way reproduce all or any part, you must request permission. The views expressed by the author do not necessarily reflect the opinion of FRIDE. If you have any comments on this -

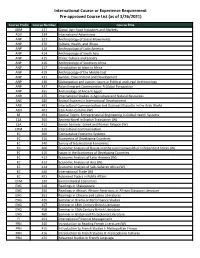

International Course Or Experience Requirement Pre-Approved Course List (As of 3/26/2021)

International Course or Experience Requirement Pre-approved Course List (as of 3/26/2021) Course Prefix Course Number Course Title ABM 427 Global Agri-Food Industries and Markets ADV 334 International Advertising ANP 321 Anthropology of Social Movements ANP 370 Culture, Health, and Illness ANP 410 Anthropology of Latin America ANP 414 Anthropology of South Asia ANP 415 China: Culture and Society ANP 416 Anthropology of Southern Africa ANP 417 Introduction to Islam in Africa ANP 419 Anthropology of the Middle East ANP 431 Gender, Environment and Development ANP 436 Globalization and Justice: Issues in Political and Legal Anthropology ANP 437 Asian Emigrant Communities: A Global Perspective ANP 455 Archaeology of Ancient Egypt ANR 475 International Studies in Agriculture and Natural Resources ANS 480 Animal Systems in International Development ARB 491 Intercultural Communication and Business Etiquette in the Arab World ASN 401 East Asian Cultures (W) BE 491 Special Topics: Entrepreneurial Engineering in Global Health Systems CLA 360 Ancient Novel in English Translation (W) CLA 412 Senior Seminar: Greek and Roman Religion (W) COM 310 Intercultural Communication EC 306 Comparative Economic Systems EC 310 Economics of Developing Countries EC 340 Survey of International Economics EC 406 Economic Analysis of Russia and the Commonwealth of Independent States (W) EC 410 Issues in the Economics of Developing Countries EC 412 Economic Analysis of Latin America (W) EC 413 Economic Analysis of Asia (W) EC 414 Economic Analysis of Sub–Saharan Africa -

Iranian Resistance Regime Change Within Reach

ONWARDS WITH THE IRANIAN RESISTANCE REGIME CHANGE WITHIN REACH Maryam Rajavi, the President-elect of the National Council of Resistance of Iran (NCRI) A Special Report Prepared By The Washington Times Advocacy Department And The U.S. Foundation For Liberty And Human Rights Iranian dissidents rally in France for the overthrow of Iran’s theocracy BY THE WASHINGTON TIMES VILLEPINTE, France — Thousands of supporters of an Iranian dissident group rallied here Saturday for the overthrow of Tehran’s theocratic regime at an event that featured speeches by several Trump admin- istration allies — including Newt Gingrich and Rudolph W. Giuliani — as well as the former head of Saudi intelligence. The boisterous event, held annually in this town just north of Paris, was organized by the National Council of Resistance of Iran, a France-based group of Iranian exiles that brings dozens of current and former U.S., European and Middle Eastern officials together to speak out in support of regime change in Tehran. While the Trump administration’s pos- ture on the issue is elusive, Mr. Giuliani drew loud cheers by asserting that the new U.S. president’s view is far different from that of his predecessor, who led world pow- ers to ease sanctions on the Islamic republic with the 2015 Iranian nuclear accord. PHOTO:TME Mr. Trump is “laser-focused on the a cheering crowd of tens of thousands welcomed National Council of Resistance of Iran President-elect Maryam Rajavi to the July 1 Free danger of Iran to the freedom of the world,” Iran Rally. NT e said Mr. -

Editors' Introduction Studying the International

Editors’ Introduction Studying the International Relations of the Asia Pacifi c: What Is the Region, What Are the Issues? Shaun Breslin and Richard Higgott Introduction or nearly three decades now, various scholars, analysts and practitioners have been hypothesising about the rise of the ‘Pacific’ or ‘Asian’ centuries. FAnalyses have been driven variously by the agendas of international security, international economic relations and increasingly a combination of the two. Though confidence in Asia’s rise was somewhat dented by the Asian financial crisis of 1997, the early years of the 21st century have seen the Pacific Century narrative begin to regain strength once again. The primary driver of this renewed rhetoric is growing American interests (if not outright concerns) about the impact of China (see Shambaugh, in Volume 2). Indeed, the recent flurry of activity by those seeking to establish the correctness of their theoretical starting point for studying the region (covered in Volume 1) is largely concerned with predicting the consequences of China’s rise; and trying to influence a policy audience (primarily in Washington) to act now to shape the nature of this rise. But it’s not just about China. As perhaps most forcefully expressed in the writings of Kishore Mahbubani (2007), there is also a growing assertiveness in some parts of Asia itself over the shift in power from the Western to eastern hemisphere. Earlier scholars from the region argued that Asia did not have to accede to the Western way of doing things – the region could ‘Say No!’ to the imposition of alien political, economic and social structures and do things their own way. -

Ernest Mandel the Meaning of the Second World War Ernest Mandel

VERSO WORLD HISTORY SERIES Ernest Mandel The Meaning of the Second World War Ernest Mandel The Meaning of the Second World War VERSO The Imprintv of New Left Books Contents One The Historical Framework Chapter 1 The Stakes 11 Chapter 2 The Immediate Causes 22 Chapter 3 The Social Forces 35 Chapter 4 Resources 47 Chapter 5 Strategy 55 Chapter 6 Weapons 66 Chapter 7 Logistics 72 Chapter 8 Science and Administration 78 Chapter 9 Ideology 85 Two Events and Results Chapter 10 The Opening Gambit in Europe 99 Chapter 11 The Unfolding World Battle 106 Chapter 12 Towards the Climax 113 Chapter 13 The Decisive Turning-Points 122 Chapter 14 The War of Attrition 130 Chapter 15 The Final Onslaught 139 Chapter 16 The Outcome 150 Chapter 17 The Aftermath 159 Chapter 18 The Legacy 169 To the memory of all those who gave their lives fighting against fascism and imperialism - in the first place all those who fell in order to transform that fight into the victory of world revolution: Abram Leon; Le6n Lesoil; Marcel Hie; Hendrik Sneevliet; Victor Widelin; Pantelis Pouliopoulos; Blasco; Tha-Thu-Tau; Cher Dou-siou; Tan Malakka; and above all to the heroic unknown editors of Czorwony Sztand- ardf who published their Trotskyist underground paper in the Warsaw Ghetto until the last days of the uprising in which they actively participated. 1. The Stakes Capitalism implies competition. With the emergence of large cor porations and cartels - i.e. the advent of monopoly capitalism - this competition assumed a new dimension. It became qualitatively more politico-economic, and therefore military-economic. -

Thirty Years of Sino-Saudi Relations

Strangers to Strategic Partners: Thirty Years of Sino-Saudi Relations STRANGERS TO STRATEGIC PARTNERS: Thirty Years of Sino-Saudi Relations JONATHAN FULTON ATLANTIC COUNCIL 1 About the Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative The Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative honors the legacy of Brent Scowcroft and his tireless efforts to build a new security architecture for the region. Our work in this area addresses the full range of security threats and challenges including the danger of interstate warfare, the role of terrorist groups and other nonstate actors, and the underlying security threats facing countries in the region. Through all of the Council’s Middle East program- ming, we work with allies and partners in Europe and the wider Middle East to protect US inter- ests, build peace and security, and unlock the human potential of the region. You can read more about our programs at www.atlanticcouncil.org/programs/middle-east-programs/. STRANGERS TO STRATEGIC PARTNERS: Thirty Years of Sino-Saudi Relations JONATHAN FULTON ISBN-13: 978-1-61977-114-7 Cover image: China’s President Xi Jinping and Saudi Arabia’s King Salman bin Abdulaziz attend the Road to the Arab Republic—the closing ceremony of the artifacts unearthed in Saudi Arabia—at China’s National Museum in Beijing, China, on March 16, 2017. Photo credit: Reuters/Lintao Zhang/Pool This report is written and published in accordance with the Atlantic Council Policy on Intellectual Independence. The au- thors are solely responsible for its analysis and recommendations. The Atlantic Council and its donors do not determine, nor do they necessarily endorse or advocate for, any of this report’s conclusions. -

Why Bahrain's Move to Make Peace Is Especially

Selected articles concerning Israel, published weekly by Suburban Orthodox Toras Chaim’s (Baltimore) Israel Action Committee Edited by Jerry Appelbaum ( [email protected] ) | Founding editor: Sheldon J. Berman Z”L Issue 8 5 7 Volume 20 , Number 3 6 Rosh Ha shana September 1 9 , 20 20 Why Bahrain’s Move to Make Peace Is Especially Courageous By Oded Granot israelhayom.com September 8, 2020 Defying Iran. but has a free market economy that doesn't rely just on oil. Bahraini King Hamad al - Khalifa surprised no one by The Bahraini economy is the fastest growing in the Arab following in the footsteps of the United Arab Emirates, world and opens up a plethora of opportunities for broad exposing his country' s long - standing clandestine relations commercial ties between the countries. On social issues, with Israel, and establishing diplomatic ties with direct too, such as wome n's rights, Bahrain is ahead of many flights between Israel and Manama. Arab countries. In the cultural realm, meanwhile, more And yet, this was a courageous move on his part, no books are published there than any other Arab country. less daring and perhaps even more so than the UAE Beyond all this, Bahrain, similar to the UAE, is an leader's trailblazing m ove last month to normalize relations exemplary model of religious moderation, as a with Israel. This is because Bahrain, a tiny island nation off counterweig ht to the radical political Islam spearheaded by the Saudi coast, is more susceptible than the UAE to Iran, Turkey and Qatar. Mohammad Bin Zayed, the crown national security threats posed by Iran. -

POLI 4067: Comparative Politics of East Asia, Fall 2007

© Wonik Kim POLI 4067 The Politics of Asia, Spring 2018 東亞政治 东亚政治 동아시아정치 東アジア政治 East Asian Politics Tuesday and Thursday 12:00 – 1:20 pm, 211 Tureaud Hall Prof. Wonik Kim, [email protected] Office: 229 Stubbs Hall Office Hours: 2:00 – 3:00 pm on Tuesday and Thursday or by appointment Men make their own history, but they do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under circumstances chosen by themselves, but under circumstances directly encountered, given and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all the dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brain of the living. Karl Marx, The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte (1852) This course provides an analytical overview of the comparative politics of East Asia, focusing on Northeast Asia (China, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan) with some emphasis on Southeast Asia. This course has at least three goals: 1) to understand important political issues, political institutions, political behaviors, contentious politics, and political economies of East Asia, 2) to provide a theoretical framework to understand important historical events that have shaped the current politics of East Asia, and 3) to overcome an ethnocentric provincialism by making explicit and implicit comparisons (e.g., China, Korean and Japan; East Asia and Euro-America). To do so, this course is divided into three parts. In Part I, we will begin with a session that equips students with a theoretical framework of comparative politics and introduces this region more generally. By focusing on the modern capital- nation-state formation in the context of colonialism and imperialism, the following sessions in Part I will provide significant historical facts and issues of China, Taiwan, Korea, Japan, and Southeast Asian countries to properly understand the substantive topics in the following parts. -

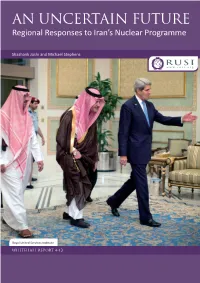

Read More > About an Uncertain Future: Regional Responses To

AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE Regional Responses to Iran’s Nuclear Programme Shashank Joshi and Michael Stephens Royal United Services Institute WHITEHALL REPORT 4-13 First Published December 2013 © The Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the Royal United Services Institute. Whitehall Report Series ISSN 1750-9432 About the Programme The Nuclear Analysis Programme at RUSI carries out comprehensive research, convenes expert discussions and holds public conferences on various contemporary aspects of nuclear disarmament and non-proliferation. The programme focuses primarily on national and international nuclear policy and strategy. Particular attention is paid to UK nuclear weapons policy, the future of international disarmament efforts, Korean Peninsula security, and the implications of a nuclear Iran. This Whitehall Report has been made possible by a grant from the MacArthur Foundation. About RUSI The Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) is an independent think tank engaged in cutting edge defence and security research. A unique institution, founded in 1831 by the Duke of Wellington, RUSI embodies nearly two centuries of forward thinking, free discussion and careful reflection on defence and security matters. For more information, please visit: www.rusi.org About Whitehall Reports Whitehall Reports are available as part of a membership package, or individually at £10.00 plus p&p (£2.00 in the UK/£4.00 overseas). Orders should be sent to the Membership Administrator, RUSI Membership Office, Whitehall, London, SW1A 2ET, United Kingdom and cheques made payable to RUSI. -

The British Monarchy, Saudi Arabia, and 9/11 by Richard Freeman and William F

EIR Counterintelligence CHARLES OF ARABIA The British Monarchy, Saudi Arabia, and 9/11 by Richard Freeman and William F. Wertz, Jr. May 15—In a webcast on Oct. 26, 2012, Lyndon LaRouche empha- sized that the Saudi Kingdom and the British Empire are one and the same institution—one extended British Empire. This is emphati- cally also the case when it comes to terrorism, and specifically to 9/11. As EIR has documented, the black ops slush fund employed by the Saudis, and in particular, by Prince Bandar bin Sultan, in sup- porting al-Qaeda, was derived from the arms deal, known as Al- Yamamah, beginning in 1985, be- YouTube tween the British company BAE Prince Charles of Arabia, shown here in Riyadh with his close friends in the Saudi royal and the Saudi Ministry of Defense family, joining in the ritual “Sword Dance,” based on ancient Bedouin traditions. and Aviation. However, there are two aspects of the 9/11 attack representative of the British Royal Family, to the cur- which have not been adequately exposed to the public rent Saudi Monarchy. to date. First, the direct relationship between the British Royal Family and the Saudi Royal Household; and A Pending Day in Court second, the top-down interface between a consortium During the course of last year, two U.S. Federal Court of Saudi banks and charitable organizations which have decisions cleared the way for the 9/11 families to pursue been identified as the financial-logistical infrastructure court cases against the perpetrators of the attacks. On of the al-Qaeda terrorist network (see below). -

![Prince Turki Al Faisal Event[1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8384/prince-turki-al-faisal-event-1-2368384.webp)

Prince Turki Al Faisal Event[1]

Press Review Report A conversation with His Royal Highness Prince Turki bin Faisal Al Saud at IPI – New York 51-52 Harbour House, Bahrain Financial Harbour, Manama, November 9, 2018 Kingdom of Bahrain Press Review Report A conversation with His Royal Highness Prince Turki bin Faisal Al Saud at IPI – New York On Friday 9 November 2018, the International Peace Institute New York (IPI New York), hosted His Royal Highness Prince Turki bin Faisal Al Saud, Chairman of the King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies. S.no Headline Publication Date Language Page (Print) Prince Turki Al Faisal: Saudi Akhbar Alkaleej – 11/11/18 Arabic - Arabia is proud of its Digital 1 judgement and will not allow any international investigations Prince Turki Al Faisal: Saudi Akhbar Alkaleej – 11/11/18 Arabic 1 Arabia is proud of its Print 2 judgement and will not allow any international investigations. Turki Al Faisal: We will not Al Qabas – Digital 10/11/18 Arabic - accept an international 3 investigation into the death of Khashoggi Turki Al Faisal: We will Palestine Times – 10/11/18 Arabic - 4 answer the question “where is Digital Khashoggi’s body” Turki Al Faisal: We will not Al Mowaten – 10/11/18 Arabic - accept an international Digital 5 investigation into the Khashoggi case Turki Al Faisal: We will not RT Arabic – 10/11/18 Arabic - accept an international Digital investigation into the murder 6 of Khashoggi and it is unjust to accuse to the Crown Prince without any proof. 2 Turki Al Faisal on an CNN Arabic – 10/11/18 Arabic - international investigation -

POLS 2560: Politics of Asia Spring 2019, Tth 215-330Pm Classroom: Mcgannon 121 Professor Nori Katagiri Email: Nori.Katagiri@Sl

POLS 2560: Politics of Asia Spring 2019, TTh 215-330pm Classroom: McGannon 121 Professor Nori Katagiri Email: [email protected] Office: McGannon 152 Phone: 977-3044 Office hours: Tuesdays 330-430pm Course Description and Objectives: This course is designed to explore some of the most important works in the literature on the politics of Asia. The regions we will cover include Northeast Asia, Southeast Asia, and parts of South Asia. We will discuss a wide range of topics that determine major courses of actions for many governments and societies in Asia, including trade, cyber security, and territorial disputes. We will also investigate US relations with countries in Asia. In this course, we seek to explore the past, present, and future of East Asian politics, economy, and security affairs analyze the nature of US relationship with East Asia understand the role of power, resources, and ideas in the formation and application of national and regional interests, and hone critical thinking on political events taking place in East Asia Required Text: Derek McDougall, Asia Pacific in World Politics, 2nd Edition (Boulder, Colo: Lynne Rienner, 2016). You must buy the designated edition of the book. Hard copies have been ordered to the SLU bookstore. Course Requirements and Grading: Map quiz: 10% of final grade The quiz will ask you to correctly spell a total of 10 Asian countries on a map. The quiz will be given on January 29. There will be no make-up quiz if you miss it. Midterm exam: 20% of final grade The midterm exam is based on the reading assignments and lecture content.