No.17 Autumn 1999 £1.00

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Committee Minutes

Planning and Regulatory Sub Committee 2 May 2000 Irvine, 2 May 2000 - At a Meeting of the Planning and Regulatory Sub-Committee of North Ayrshire Council at 10.00 a.m. Present David Munn, Robert Reilly, Jack Carson, Ian Clarkson, Elizabeth McLardy, David O'Neill, Robert Rae, John Reid and John Sillars. In Attendance I.T. Mackay, Assistant Chief Executive, and J. Kerr, Principal Licensing and District Court Officer (Legal and Regulatory); and M. McKeown, Administration Officer (Chief Executive's). Chair Mr. Munn in the Chair. Apologies for Absence Samuel Gooding. 1. Arran Local Plan Area N/99/02076/PP: Corrie: Ferry View Mrs. J. White, Ferry View, Corrie, Isle of Arran has applied for Planning Permission for the siting of a 1350 litre domestic fuel tank and the replacement of front and rear doors at that address. A representation has been received from Arran Estates Office, Brodick, Isle of Arran. The Sub Committee having considered the terms of the representation, agreed to grant the application subject to the following condition:- (1) That within one month of the date of this permission, details of the construction and finish of the fire wall required between the dwellinghouse and the fuel tank hereby approved shall be submitted for the written approval of North Ayrshire Council as Planning Authority. 2. Irvine/Kilwinning Local Plan Area (a) N/00/00106/PP: Kilwinning: Torranyard: 3 The Bungalows Mr. W. McNulty, 3 The Bungalows, Torranyard, Kilwinning has applied for Planning Permission for the erection of a boundary garden wall and entrance gates at that address. An objection has been received from Mr. -

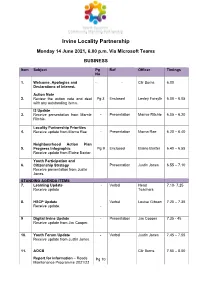

Irvine Locality Partnership

Irvine Locality Partnership Monday 14 June 2021, 6.00 p.m. Via Microsoft Teams BUSINESS Item Subject Pg Ref Officer Timings No 1. Welcome, Apologies and - - Cllr Burns 6.00 Declarations of Interest. Action Note 2. Review the action note and deal Pg 3 Enclosed Lesley Forsyth 6.00 – 6.05 with any outstanding items. I3 Update 3. Receive presentation from Marnie - Presentation Marnie Ritchie 6.05 – 6.20 Ritchie. Locality Partnership Priorities 4. Receive update from Morna Rae - Presentation Morna Rae 6.20 – 6.40 Neighbourhood Action Plan 5. Progress Infographic Pg 9 Enclosed Elaine Baxter 6.40 – 6.55 Receive update from Elaine Baxter. Youth Participation and 6. Citizenship Strategy Presentation Justin Jones 6.55 – 7.10 Receive presentation from Justin Jones. STANDING AGENDA ITEMS 7. Learning Update - Verbal Head 7.10- 7.25 Receive update Teachers 8. HSCP Update Verbal Louise Gibson 7.25 – 7.35 Receive update. - 9 Digital Irvine Update - Presentation Jim Cooper 7.35 - 45 Receive update from Jim Cooper. 10. Youth Forum Update - Verbal Justin Jones 7.45 – 7.55 Receive update from Justin Jones. 11. AOCB Cllr Burns 7.55 – 8.00 Report for information – Roads Pg 10 Maintenance Programme 2021/22 Date of Next Meeting: Monday 27 September 2021 at 6.00 pm via Microsoft Teams Distribution List Elected Members Community Representative Councillor Marie Burns (Chair) Sylvia Mallinson (Vice Chair) Councillor Ian Clarkson Diane Dean (Co- opted) Councillor John Easdale Donna Fitzpatrick Councillor Robert Foster David Mann Councillor Scott Gallacher Peter Marshall Councillor Margaret George Janice Murray Councillor Christina Larsen Annie Small Councillor Shaun Macaulay Ian Wallace Councillor Louise McPhater Councillor Angela Stephen CPP/Council Representatives Lesley Forsyth, Lead Officer Scott McMillan, Scottish Fire and Rescue Service Andy Dolan, Police Scotland Elaine Baxter, Locality Officer Meeting: Irvine Locality Partnership Date/Venue: 15 March 2021 – Virtual Meeting at 6.00 p.m. -

Winter Service Plan

1 INTRODUCTION The Ayrshire Roads Alliance within the Department of Neighbourhood Services is responsible for providing the winter service for East Ayrshire including:- Establishing standards Establishing treatment priorities Day to day direction of operations Monitoring performance Liaison with adjoining Councils and Emergency Services The Winter Service Plan was revised during the summer of 2011 to introduce the concepts and to follow the format provided in the code of practice 'Well Maintained Highways’, which was updated in May 2011. There is additional and more detailed information available (within the Ayrshire Roads Alliance Quality Management System) for personnel involved with the management and implementation of this Winter Service Plan. The Winter Service Plan will be reviewed annually and amended and updated before the 1st of October to include any revisions and changes considered necessary and appropriate to the service delivery. 2 CONTENTS Page Page 1.0 Statement of Policies and Responsibilities 04 5.0 Organisational Arrangements and 1.1 Statutory Obligations and Policy 04 Personnel 09 1.2 Responsibilities 04 5.1 Organisation chart and employee 1.3 Decision Making Process 05 responsibilities 09 1.4 Liaison arrangements with other authorities 05 5.2 Employee duty schedules, rotas and standby arrangements 10 1.5 Resilience Levels 06 5.3 Additional Resources 10 2.0 Quality 06 5.4 Training 10 2.1 Quality management regime 06 5.5 Health and safety procedures 10 2.2 Document control procedures 06 6.0 Plant, Vehicles and Equipment -

Download the Hunterston Power Station Off-Site Emergency Plan

OFFICIAL SENSITIVE – FOR REGIONAL RESILIENCE PARTNERSHIP USE ONLY HUNTERSTON B NUCLEAR POWER STATION Hunterston B Nuclear Power Station Off-site Contingency Plan Prepared by Ayrshire Civil Contingencies Team on behalf of North Ayrshire Council For the West of Scotland Regional Resilience Partnership WAY – No. 01 (Rev. 4.0) Plan valid to 21 May 2020 OFFICIAL SENSITIVE OFFICIAL SENSITIVE – FOR REGIONAL RESILIENCE PARTNERSHIP USE ONLY HUNTERSTON B NUCLEAR POWER STATION 1.3 Emergency Notification – Information Provided When an incident occurs at the site, the on site incident cascade will be implemented and the information provided by the site will be in the form of a METHANE message as below: M Major Incident Yes / No Date Time E Exact Location Wind Speed Wind Direction T Type Security / Nuclear / etc H Hazards Present or suspected Radiological plume Chemical Security / weapons Fire A Access Details of the safe routes to site RVP N Number of casualties / Number: missing persons Type: Severity E Emergency Services Present or Required On arrival, all emergency personnel will be provided with a dosimeter which will measure levels of radiation and ensure that agreed limits are not reached. Emergency Staff should report to the site emergency controller (see tabard in Section 17.5). Scottish Fire and Rescue will provide a pre-determined attendance of 3 appliances and 1 Ariel appliance incorporating 2 gas suits. In addition to this Flexi Duty Managers would also be mobilised. A further update will be provided by the site on arrival. WAY – No. -

Residents Zones

BELLESLEYHILL ROAD TWEED STREET 12 47 61 Mast 12 15 17 BELLESLEYHILL ROAD 22 30 39 84 76 1 52 13 45 15b LANSDOWNE ROAD 90 El 15c 15a 2 41 Sub Sta 26 1 2 9 LB 59 45 El Sub Sta 2 ALDERSTON AVENUE 32 TEVIOT STREET 2 23 TWEED STREET Falkland Yard 7 45 42 OSWALD ROAD 11 14 43 1 Newton Park 46 5.4m 12 2 7 48 4 11 21 Oswald 42 15 8.6m 66 1 35 16 Court 14 25 26 57 5 16 39 9 10 27 10.8m 2 43 ALDERSTON AVENUE 18 37 17 11 18 40 4.1m 35 20 78 ALDERSTON PARK 2 47 30 1 FALKLAND PLACE EAST PARK ROAD L Twr 2 38 29 49 55 1 21 1 1 22 29 2 56 Tennis Court TEVIOT 23 STREET 12 PROMENADE EAST PARK ROAD 33 17 16 31 14 32 4 25 50 3 ALDERSTON PLACE 14 FALKLAND ROAD MCCOLGAN 12 8a HUNTER'S AVENUE 1a Works 31a 23a 21 10.8m 1 12 23 19 41 16 68 PLACE SL 11 BELLESLEYHILL AVENUE ROSSLYN PLACE 11 24 30 13 2 17 15 31 9 18 2 Pipe FALKLAND PARK ROAD 13b 15 51 21 4 20 1 El 25 9 Sub Sta 11 11 5 El Sub Sta 7 Bowling Green 17 46 1 44 8.6m 3 1 19 4.5m Daisy Cottages 29 WYBURN PLACE Water Point 23 12 El Sub Sta 48 3 35a 58 1 9 1 45 Bowling Green GARDENS Northfield Court 11 2 El Sub Sta 44 FALKLAND PARK ROAD 13 5 1a 2 9.7m 19 CAMBUSLEA 1 NORTHFIELD AVENUE 21 29 Bowling Green 12 Depot 23 25 27 N 6 10.9m 1 35 Northfield 8 37 Bowling Green 36 Gardens 39 42a 11 8.1m CAMBUSLEA ROAD Pavilion 10 2 AYR Bowling Green FS Mean Low Water Springs 1 21 Sand 18 10.7m 41 20 15 43 21 LB SALTPANS ROAD 42 2 1 PRESTWICK ROAD 28 4 Manse 24 32b 32 32a 26 34 6 10.7m 2 42 6.0m Newton On Ayr 33 FALKLAND PARK ROAD 44 NORTHFIELD AVENUE 47 1a Shingle 32 10 10.6m ESS Hotel 54 Tank 5.8m 57 Mean High Water -

Cottage and Railway Loading Dock, Benslie Project KHAP101

Cottage and Railway Loading Dock, Benslie Project KHAP101 Archaeological Investigation Report Andy Baird, Roger Griffith, Chris Hawksworth, Jeni Park and Ralph Shuttleworth March 2014 Contents Quality Assurance 3 Acknowledgements 3 List of Figures 4 Introduction 5 Designations and Legal Constraints 5 Project Background by Roger S. Ll. Griffith 5 Time Line for the Ardrossan - Doura - Perceton Branch by Roger S. Ll. Griffith 7 Project Works by Ralph Shuttleworth Introduction 8 Map Evidence and Dating 9 Archaeological Investigations 11 Simplified plan drawing of the cottage 15 A Reconstruction of the Nature of the Building 16 The People by Jeni Park 18 Inland Revenue land Survey by Chris Hawksworth 23 A Comparison of the Windows at Benslie Cottage and Kilwinning Abbey by Ralph Shuttleworth 25 Discussions and Conclusion by Ralph Shuttleworth 27 The Hurry by Roger S. Ll. Griffith 30 Finds by Andy Baird 34 Addendum, May 2014 37 Appendix 1. List of Contexts 38 Appendix 2. List of Finds 39 Appendix 3. List of Structures 41 Appendix 4. List of Drawings 41 Appendix 5. List of Photographs 42 Drawings 1-7 44-50 Quality Assurance This report covers works which have been undertaken in keeping with the aims and principles set out in the Project Design. It has been prepared for the exclusive use of the commissioning party and unless previously agreed in writing by Kilwinning Heritage, no other party may use, make use of or rely on the contents of the report. No liability is accepted by Kilwinning Heritage for any use of this report, other than the purposes for which it was originally prepared and provided. -

STD Code Book for 1984 Based on Haddenham & Long Crendon Issue 4, 1984

STD Code Book for 1984 Based on Haddenham & Long Crendon Issue 4, 1984 01 London 0207 Burnopfield 0200 Clitheroe 0207 Consett 0200 5 Gisburn 0207 Dipton 0200 6 Slaidburn 0207 Ebchester 0200 7 Bolton-by-Bowland 0207 Edmundbyers 0200 8 Dunsop Bridge 0207 Lanchester (Co Durham) 0202 Bournemouth 0207 Rowlands Gill 0202 Broadstone 0207 Stanley (Co Durham) 0202 Canford Cliffs 0208 Bodmin 0202 Christchurch (Dorset) 0208 Lanivet 0202 Ferndown 0208 81 Wadebridge 0202 Lytchett Minster 0208 82 Cardinham 0202 Parkstone 0208 84 St Mabyn 0202 Poole 0208 86 Trebetherick 0202 Verwood 0208 88 Port Isaac 0202 Wimborne (Dorset) 0209 Camborne 0203 Bedworth 0209 Porthtowan 0203 Chapel End 0209 Portreath 0203 Coventry 0209 Praze 0203 Nuneaton 0209 Redruth 0203 Royal Show 0209 St Day 0203 Wolston 0209 Stithians 0203 33 Keresley (Coventry) 021 Birmingham 0204 Bolton 0220 23 Histon 0204 Farnworth 0220 26 Comberton 0204 Horwich (Lancs) 0220 29 West Wratting 0204 Turton 0220 5 Teversham 0204 81 Belmont Village 0221 22 Limpley Stoke 0204 88 Tottington 0221 4 Trowbridge (4 & 5 fig nos) 0205 Boston (Lincs) 0221 6 Bradford-on-Avon 0205 73 Langrick 0221 7 Saltford (4 fig nos) 0205 78 Stickney 0222 Caerphilly 0205 79 Hubbert's Bridge 0222 Cardiff 0205 84 New Leake 0222 Dinas Powys 0205 85 Fosdyke 0222 Penarth 0205 86 Sutterton 0222 Pentyrch 0206 Colchester 0222 Radyr (Sth Glam) 0206 Great Bentley 0222 Senghenydd 0206 Nayland (Colchester) 0222 Sully 0206 West Mersea 0222 Taffs Well 0206 22 Wivenhoe 0223 Cambridge 0206 28 Rowhedge 0224 Aberdeen 0206 30 Brightlingsea 0224 -

Constitution and Cup Competition Rules

SCOTTISH FOOTBALL ASSOCIATION LIMITED ASSOCIATION FOOTBALL SCOTTISH SCOTTISH FOOTBALL ASSOCIATION LIMITED ASSOCIATION FOOTBALL SCOTTISH CONSTITUTION AND www.scottishamateurfa.co.uk CUP COMPETITION AFFILIATED TO TO THE THE RULES SEASON 2014-2015 Dates of Council Meetings 2014 25th July 5th September 14th November 2015 9th January 13th March 8th May THE SCOTTISH AMATEUR FOOTBALL ASSOCIATION Instituted 1909 Season 2014/2015 Patrons The Rt. Hon. The Earl of Glasgow. The Rt. Hon. Lord Weir of Eastwood. Rt. Hon. The Lord Provosts of Edinburgh, Glasgow, Dundee & Aberdeen OFFICE BEARERS (2014 – 2015) Hon President Hugh Knapp (Life Member) 7 Struther Street, Larkhall. ML9 1PE (M) 07852633912 Honorary Vice President To be Confirmed Honorary Treasurer George Dingwall, (Central Scottish A.F.L.) 27 Owendale Avenue, Bellshill, Lanarkshire ML4 1NS (H) 01698 749044 (M) 07747 821274 E-Mail: [email protected] NATIONAL SECRETARY Thomas McKeown MCIBS Scottish Amateur Football Association Hampden Park, Glasgow G42 9DB (B) 0141 620 4550 (Fax) 0141 620 4551 E-mail: [email protected] TECHNICAL ADMINISTRATOR / ADVISER Stephen McLaughlin Scottish Amateur Football Association Hampden Park, Glasgow G42 9DB (B) 0141 620 4552 (Fax) 0141 620 4551 E-mail: [email protected] ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT Mary Jardine Scottish Amateur Football Association Hampden Park, Glasgow G42 9DB (B) 0141 620 4550 (Fax) 0141 620 4551 E-mail: [email protected] 3 PAST OFFICE BEARERS PRESIDENTS 1909-21 Robert A. Lambie (Glasgow F.P.A.F.L.) 1921-23 James M. Fullarton (Scottish A.F.L.) 1923-24 John T. Robson (Moorpark A.F.C.) 1924-28 Peter Buchanan (Whitehill F.P.A.F.C.) 1928-30 James A. -

The Broch - Aberdeenshire Cup Winners 2014-15

The Broch - Aberdeenshire Cup Winners 2014-15 Official Match Programme £2.00 Fraserburgh v Dalbeattie Star William Hill Scottish Cup 1st Round Bellslea Park, Fraserburgh Saturday 26th September 2015. Kick-off 3.00 pm Official Matchday Programme Vol 6. No. 8 Fraserburgh Football Club (Formed 1910) Manager: Mark Cowie Bellslea Park, Seaforth Street, Fraserburgh, Aberdeenshire, AB43 9BB, Tel No. 01346 518444 Assistant Manager: James Duthie Chairman/Secretary: Finlay Noble Coaching Staff: Alex Mair, Stevie Doak Vice Chairman: Peter Bruce Brent Bruce, Antony Sherlock & Charles West Directors: Peter Bruce, Peter Cowe, Robert Cowe, Community Coaches: Shelley Sutherland & Graeme Noble James Gibb, David Milne, Calvin Morrice, Kit Man: Jordan Buchan Ewan Mowat, Jason Nicol & Finlay Noble Team Captain: Russell McBride Treasurer: Stephen Sim Club Physio: Ross Cardno Youth Co-ordinator: Alex Mair Assistant Physio: Leanne Reid Web Master: Finlay Noble Club Doctor: Dr Michael Dick Committee Members: Club Honours Mike Barbour, Angela Chegwyn, Stuart Ellis, Highland League Champions: 1932/33, 1937/38, 2001/02 Frank Goodall, Sam Mackay, Iain Milne, League Cup Winners: Lewis Milne, Craig Mowat, Alex Noble, 1958/59, 2005/06 Stephen Sim, Mark Simpson & Colin West Qualifying Cup Winners: 1957/58, 1995/96, 2006/07 Programme Contributors: Mark Simpson (Editor) Aberdeenshire Cup Winners: Finlay Noble 1910/11, 1937/38, 1955/56, 1963/64, Barry Walker (Photographer) 1972/73, 1975/76, 1996/97, 2012/13, 2014/15 Email: [email protected] Aberdeen Charity -

I General Area of South Quee

Organisation Address Line 1 Address Line 2 Address Line3 City / town County DUNDAS PARKS GOLFGENERAL CLUB- AREA IN CLUBHOUSE OF AT MAIN RECEPTION SOUTH QUEENSFERRYWest Lothian ON PAVILLION WALL,KING 100M EDWARD FROM PARK 3G PITCH LOCKERBIE Dumfriesshire ROBERTSON CONSTRUCTION-NINEWELLS DRIVE NINEWELLS HOSPITAL*** DUNDEE Angus CCL HOUSE- ON WALLBURNSIDE BETWEEN PLACE AG PETERS & MACKAY BROS GARAGE TROON Ayrshire ON BUS SHELTERBATTERY BESIDE THE ROAD ALBERT HOTEL NORTH QUEENSFERRYFife INVERKEITHIN ADJACENT TO #5959 PEEL PEEL ROAD ROAD . NORTH OF ENT TO TRAIN STATION THORNTONHALL GLASGOW AT MAIN RECEPTION1-3 STATION ROAD STRATHAVEN Lanarkshire INSIDE RED TELEPHONEPERTH ROADBOX GILMERTON CRIEFFPerthshire LADYBANK YOUTHBEECHES CLUB- ON OUTSIDE WALL LADYBANK CUPARFife ATR EQUIPMENTUNNAMED SOLUTIONS ROAD (TAMALA)- IN WORKSHOP OFFICE WHITECAIRNS ABERDEENAberdeenshire OUTSIDE DREGHORNDREGHORN LOAN HALL LOAN Edinburgh METAFLAKE LTD UNITSTATION 2- ON ROAD WALL AT ENTRANCE GATE ANSTRUTHER Fife Premier Store 2, New Road Kennoway Leven Fife REDGATES HOLIDAYKIRKOSWALD PARK- TO LHSROAD OF RECEPTION DOOR MAIDENS GIRVANAyrshire COUNCIL OFFICES-4 NEWTOWN ON EXT WALL STREET BETWEEN TWO ENTRANCE DOORS DUNS Berwickshire AT MAIN RECEPTIONQUEENS OF AYRSHIRE DRIVE ATHLETICS ARENA KILMARNOCK Ayrshire FIFE CONSTABULARY68 PIPELAND ST ANDREWS ROAD POLICE STATION- AT RECEPTION St Andrews Fife W J & W LANG LTD-1 SEEDHILL IN 1ST AID ROOM Paisley Renfrewshire MONTRAVE HALL-58 TO LEVEN RHS OFROAD BUILDING LUNDIN LINKS LEVENFife MIGDALE SMOLTDORNOCH LTD- ON WALL ROAD AT -

Download Pdf

AYRSHIRE MONOGRAPHS NO.25 The Street Names of Ayr Rob Close Published by Ayrshire Archaeological and Natural History Society First published 2001 Printed by The Cromwell Press Ltd, Trowbridge, Wiltshire Rob Close is the author of Ayrshire and Arran: An Illustrated Architectural Guide (1992), and is presently co-editor of Ayrshire Notes. He has also contributed articles to Scottish Local History, Scottish Brewing Archive and other journals. He lives near Drongan with his long-suffering partner, Joy. In 1995 he was one half of the Scottish Handicap Doubles Croquet Champions. Cover design by David McClure. 1SBN 0 9527445 9 7 THE STREET NAMES OF AYR 1 INTRODUCTION Names have an important role in our lives: names of people, names of places, and names of things. In an enclosed, small community, these names remain informal, but as the community grows, and as travel and movement become commoner, then more formalised names are required, names which will prevent confusion. Formal and informal names can exist alongside one another. During the course of preparing this book, I agreed to meet some friends on the road between ‘Nick’s place’ and ‘the quarry’: that we met successfully was due to the fact that we all recognised and understood these informal place names. However, to a different cohort of people, ‘Nick’s place’ is known as ‘the doctor’s house’, while had we been arranging this rendezvous with people unfamiliar with the area, we would have had to fall back upon more formal place names, names with a wider currency, names with ‘public’ approval, whether conferred by the local authority, the Post Office or the Ordnance Survey. -

Roads Winter Service and Weather Emergencies Plan 2019/20

NORTH AYRSHIRE COUNCIL 29 October 2019 Cabinet Title: Roads Winter Service and Weather Emergencies Plan 2019/20 Purpose: To seek approval from Cabinet for the Roads Winter Service and Weather Emergencies Plan 2019/20. Recommendation: That Cabinet (a) approves the Roads Winter Service and Weather Emergencies Plan 2019/20 and (b) notes the preparations and developments contained in the Winter Preparation Action Plan. 1. Executive Summary 1.1 North Ayrshire Council has a statutory obligation, under Section 34 of the Roads (Scotland) Act 1984, to take such steps as it considers reasonable to prevent snow and ice endangering the safe passage of pedestrians and vehicles over public roads which by definition includes carriageways, footways, footpaths, pedestrian precincts, etc. 1.2 The Council is also responsible for the management and operation of the coastal flood protection controls at Largs and Saltcoats. The Council will close the flood gates on the promenades and erect the flood barriers at Largs Pier in advance of predicted severe weather with minimum disruption to promenade users and the Largs to Cumbrae ferry. Coastal flooding can occur at any time and, accordingly, the Council provides this service throughout the year. 1.3 A review of the Council's Winter & Weather Emergencies Service was undertaken over the summer months. The 2019/20 Winter Preparation Action Plan has been developed to ensure adequate preparations and effective arrangements are in place for 2019/20. The Winter Preparation Action Plan is included at Appendix 1. 1.4 The Roads Winter Service and Weather Emergencies Plan 2019/20 is contained at Appendix 2.