Xamk Opinnäytteen Kirjoitusalusta Versio 14022017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of Video Game Consoles Introduction the First Generation

A History of Video Game Consoles By Terry Amick – Gerald Long – James Schell – Gregory Shehan Introduction Today video games are a multibillion dollar industry. They are in practically all American households. They are a major driving force in electronic innovation and development. Though, you would hardly guess this from their modest beginning. The first video games were played on mainframe computers in the 1950s through the 1960s (Winter, n.d.). Arcade games would be the first glimpse for the general public of video games. Magnavox would produce the first home video game console featuring the popular arcade game Pong for the 1972 Christmas Season, released as Tele-Games Pong (Ellis, n.d.). The First Generation Magnavox Odyssey Rushed into production the original game did not even have a microprocessor. Games were selected by using toggle switches. At first sales were poor because people mistakenly believed you needed a Magnavox TV to play the game (GameSpy, n.d., para. 11). By 1975 annual sales had reached 300,000 units (Gamester81, 2012). Other manufacturers copied Pong and began producing their own game consoles, which promptly got them sued for copyright infringement (Barton, & Loguidice, n.d.). The Second Generation Atari 2600 Atari released the 2600 in 1977. Although not the first, the Atari 2600 popularized the use of a microprocessor and game cartridges in video game consoles. The original device had an 8-bit 1.19MHz 6507 microprocessor (“The Atari”, n.d.), two joy sticks, a paddle controller, and two game cartridges. Combat and Pac Man were included with the console. In 2007 the Atari 2600 was inducted into the National Toy Hall of Fame (“National Toy”, n.d.). -

Visual Novel Game Critical Hit Free Download Top 15 Best Visual Novels of All Time on PC & Steam

visual novel game critical hit free download Top 15 Best Visual Novels of All Time on PC & Steam. From mind-blowing twists to heartwarming stories, we’ve got you covered. Home » Galleries » Features » Top 15 Best Visual Novels of All Time on PC & Steam. Visual Novels are one of the oldest genres around for gaming. As such, there’s been a ton of them. While they’ve largely kept to PC, they do sometimes dive into the console world. But there’s no denying that the best visual novels can be found on PC and – more specifically – Steam. Here they are, hand-picked by us for you. Here are the best visual novels of all time, available for you to download on PC and steam. Best Visual Novels on PC and Steam. Umineko (When They Cry) – Umineko is a visual novel in the truest sense of the term. Meaning there’s no gameplay to speak of at all; the entire ‘game’ is just a matter of clicking through copious amounts of text and watching as the story unfold. Despite the sluggish start to the first three episodes, things pick up dramatically once the creepy stuff kicks in, and Umineko stands tall as one of the most intriguing and engaging visual novel stories we’ve ever played. That soundtrack too, though. Best Visual Novels on PC and Steam. Higurashi (When They Cry) – Higurashi is a predecessor of sorts to Umineko, and while its story is just as gripping, we don’t recommend starting with this one unless you enjoyed what you saw of Umineko. -

Press Release Company Name : Capcom Co., Ltd

October 31, 2013 Press Release Company Name : Capcom Co., Ltd. Representative: Haruhiro Tsujimoto, President and COO (Company Code: 9697 Tokyo Stock Exchange) Contact: Public Relations and Investor Relations Office Phone Number: +81-6-6920-3623 Favorable Increase on Financial Results for ended September 30, 2013 16.9% increase in Net Sales, 15.2% increase in Operating Income from Previous Term - “Monster Hunter 4” and Capcom pachislo machine contributed to the highest records at all levels for the first half of a fiscal year - Capcom Co., Ltd. would like to announce that net sales increased to 53,234 million yen (up 16.9% from the previous year) in the 6 months of fiscal year ending March 31, 2014. As for profits, operating income increased to 7,509 million yen (up 15.2% from the previous year), and ordinary income increased to 8,190 million yen (up 34.8 % from the previous year). Net income for the current period increased to 4,950 million yen (up 20.0 % from the previous year). During the 6 months, the feature title “Monster Hunter 4” is the highest ever for any third-party Nintendo 3DS title in Japan by becoming a big hit with shipment of 2.8 million units* in the Digital Contents business. In addition, “Resident Evil Revelations” and “Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney - Dual Destinies” also basically achieved projected sales. *3 million units as of October 15, 2013 In the Amusement Equipments business, “Devil May Cry 4”, which was released in September, realized better-than-expected sales, serving to drive sales expansion and support earnings. -

Understanding Visual Novel As Artwork of Visual Communication Design

MUDRA Journal of Art and Culture Volume 32 Nomor 3, September 2017 292-298 P-ISSN 0854-3461, E-ISSN 2541-0407 Understanding Visual Novel as Artwork of Visual Communication Design DENDI PRATAMA, WINNY GUNARTI W.W, TAUFIQ AKBAR Departement of Visual Communication Design, Fakulty of Language and Art Indraprasta PGRI. University, Jakarta Selatan, Indonesia [email protected] Visual Novel adalah sejenis permainan audiovisual yang menawarkan kekuatan visual melalui narasi dan karakter visual. Data dari komunitas pengembang Visual Novel (VN) Project Indonesia menunjukkan masih terbatasnya pengembang game lokal yang memproduksi Visual Novel Indonesia. Selain itu, produksi Visual Novel Indonesia juga lebih banyak dipengaruhi oleh gaya anime dan manga dari Jepang. Padahal Visual Novel adalah bagian dari produk industri kreatif yang potensial. Studi ini merumuskan masalah, bagaimana memahami Visual Novel sebagai karya seni desain komunikasi visual, khususnya di kalangan mahasiswa? Penelitian ini merupakan studi kasus yang dilakukan terhadap mahasiswa desain komunikasi visual di lingkungan Universitas Indraprasta PGRI Jakarta. Hasil penelitian menunjukkan masih rendahnya tingkat pengetahuan, pemahaman, dan pengalaman terhadap permainan Visual Novel, yaitu di bawah 50%. Metode kombinasi kualitatif dan kuantitatif dengan pendekatan semiotika struktural digunakan untuk menjabarkan elemen desain dan susunan tanda yang terdapat pada Visual Novel. Penelitian ini dapat menjadi referensi ilmiah untuk lebih mengenalkan dan mendorong pemahaman tentang Visual Novel sebagai karya seni Desain Komunikasi Visual. Selain itu, hasil penelitian dapat menambah pengetahuan masyarakat, dan mendorong pengembangan karya seni Visual Novel yang mencerminkan budaya Indonesia. Kata kunci: Visual novel, karya seni, desain komunikasi visual Visual Novel is a kind of audiovisual game that offers visual strength through the narrative and visual characters. -

Links to the Past User Research Rage 2

ALL FORMATS LIFTING THE LID ON VIDEO GAMES User Research Links to Game design’s the past best-kept secret? The art of making great Zelda-likes Issue 9 £3 wfmag.cc 09 Rage 2 72000 Playtesting the 16 neon apocalypse 7263 97 Sea Change Rhianna Pratchett rewrites the adventure game in Lost Words Subscribe today 12 weeks for £12* Visit: wfmag.cc/12weeks to order UK Price. 6 issue introductory offer The future of games: subscription-based? ow many subscription services are you upfront, would be devastating for video games. Triple-A shelling out for each month? Spotify and titles still dominate the market in terms of raw sales and Apple Music provide the tunes while we player numbers, so while the largest publishers may H work; perhaps a bit of TV drama on the prosper in a Spotify world, all your favourite indie and lunch break via Now TV or ITV Player; then back home mid-tier developers would no doubt ounder. to watch a movie in the evening, courtesy of etix, MIKE ROSE Put it this way: if Spotify is currently paying artists 1 Amazon Video, Hulu… per 20,000 listens, what sort of terrible deal are game Mike Rose is the The way we consume entertainment has shifted developers working from their bedroom going to get? founder of No More dramatically in the last several years, and it’s becoming Robots, the publishing And before you think to yourself, “This would never increasingly the case that the average person doesn’t label behind titles happen – it already is. -

Out of Base Mini-Blinds at the Mokapu Mall Grand Information, Inhabited the Tickets and Opening

INSIDE SEMPER FIT MARINE/SAILOR OF Friends of the Marina A-2 THE YEAR AESC Sholarship A-8 B4 Semper Fit Opening B-1 A-8 L va, 27# No. 16 Serving the base of choice for the 21st century April 3011998= y on the Shoppers ring line .. flock to new mall swung open to the public LCpI. Trent Lowry the first time, though. Combat Correspondent "This is so convenient and Bustling like a beehive, close to home," said Mary the official opening of the Ann Juarez, a family mem- Mokapu Mall here ber. "You really don't have Saturday was overrun by to go off base to shop any- swarms of more. You shoppers really can't eager to see ask for any- all the com- thing else." plex has to M W R. offer. planned Merchants events for the and customers entire day, alike were keeping cus- excited with tomers happy Digital photo by Cpl. Barry Melton the potential until 11 p.m. for success the Adults were 3/3 conducts SPT Mall promis- able to get LCpI. Michael Roby, a fire team leader with I Company 3d Battalion, 3d Marines, is next in line to fire the M-203 grenade launcher during es. haircuts at Standard Proficiency Test training at Schofield Barracks. The Marines were graded on their ability to fire various weapons by officers and staff "This is such the new bar- NCOs of 2/3, and 3/3 will use the SPT in preparation for its upcoming deployment in December. a fabulous ber shop building and while the kids center, I feel played the very fortunate new Jet Ski to be here," video game at Housing gets the lead said Pam Digital photo by LCpI. -

Q1 2007 8 Table of the Punch Line Contents

Q1 2007 8 Table of The Punch Line Contents 4 On the Grand Master’s Stage 34 Persona Visits the Wii Line Strider–ARC AnIllustratedCampoutfortheWii 6 Goading ‘n Gouging 42 Christmas Morning at the Ghouls‘nGoblinsseries Leukemia Ward TokyoGameShow2006 12 That Spiky-Haired Lawyer is All Talk PhoenixWright:AceAttorney–NDS 50 A Retrospective Survival Guide to Tokyo Game Show 14 Shinji Mikami and the Lost Art of WithExtra-SpecialBlueDragon Game Design Preview ResidentEvil-PS1;P.N.03,Resident Evil4-NGC;GodHand-PS2 54 You’ve Won a Prize! Deplayability 18 Secrets and Save Points SecretofMana–SNES 56 Knee-Deep in Legend Doom–PC 22 Giving Up the Ghost MetroidII:ReturnofSamus–NGB 58 Killing Dad and Getting it Right ShadowHearts–PS2 25 I Came Wearing a Full Suit of Armour But I Left Wearing 60 The Sound of Horns and Motors Only My Pants Falloutseries Comic 64 The Punch Line 26 Militia II is Machinima RuleofRose-PS2 MilitiaII–AVI 68 Untold Tales of the Arcade 30 Mega Microcosms KillingDragonsHasNever Wariowareseries BeenSoMuchFun! 76 Why Game? Reason#7:WhyNot!? Table Of Contents 1 From the Editor’s Desk Staff Keep On Keeping On Asatrustedfriendsaidtome,“Aslong By Matthew Williamson asyoukeepwritingandcreating,that’s Editor In Chief: Staff Artists: Matthew“ShaperMC”Williamson Mariel“Kinuko”Cartwright allIcareabout.”Andthat’swhatI’lldo, [email protected] [email protected] It’sbeenalittlewhilesinceourlast andwhatI’llhelpotherstodoaswell. Associate Editor: Jonathan“Persona-Sama”Kim issuecameout;Ihopeyouenjoyedthe Butdon’tworryaboutThe Gamer’s Ancil“dessgeega”Anthropy [email protected] anticipation.Timeissomethingstrange, Quarter;wehavebigplans.Wewillbe [email protected] Benjamin“Lestrade”Rivers though.Hasitreallybeenovertwo shiftingfromastrictquarterlysched- Assistant Editor: [email protected] yearsnow?Itgoessofast. -

Game Title: Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney Platform: Nintendo DS

Game Title: Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney Platform: Nintendo DS (version reviewed here), Game Boy Advance, IPhone, Nintendo Wii Genre: Adventure Release Date: OctoBer 12, 2005 Developer: Capcom Publisher: Capcom Game Writer/Creative Director/Narrative Designer: Shu Takumi Author of this Review: Amy Li School: Rochester Institute of Technology Overview Phoenix Wright: Ace Attorney is the story of the rookie defense attorney Phoenix Wright searching for an old friend in the courtroom. His roller coaster court cases take him to his goal; however, when he meets his friend again, he discovers this friend is no longer the person he knew. Despite their status now as enemies, Wright involves himself in a case that digs into the past to find out why his friend's heart has changed. Characters Taking into account all five cases available in the game, the cast is large and varied. As a result, only the characters featured prominently in the chief narrative will Be descriBed here. • Phoenix Wright is a rookie defense attorney serving as the player's avatar. Wright provides small insights and assistance through self-contained thoughts. When removed from the role as a player, Wright may seem slightly slow and reliant on luck and Bluff to win his cases. However, he presents the character of an honest, determined man who Believes in his clients' innocence—the kind of man that every person should hope his or her defense lawyer to be. • Miles Edgeworth is a seasoned, undefeated prosecutor, rumored to run Backroom deals and tamper with evidence to oBtain victory and maintain his 'undefeated' prestige. -

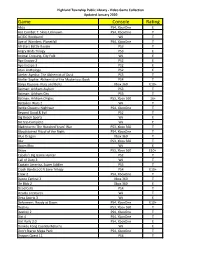

Game Console Rating

Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Abzu PS4, XboxOne E Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown PS4, XboxOne T AC/DC Rockband Wii T Age of Wonders: Planetfall PS4, XboxOne T All-Stars Battle Royale PS3 T Angry Birds Trilogy PS3 E Animal Crossing, City Folk Wii E Ape Escape 2 PS2 E Ape Escape 3 PS2 E Atari Anthology PS2 E Atelier Ayesha: The Alchemist of Dusk PS3 T Atelier Sophie: Alchemist of the Mysterious Book PS4 T Banjo Kazooie- Nuts and Bolts Xbox 360 E10+ Batman: Arkham Asylum PS3 T Batman: Arkham City PS3 T Batman: Arkham Origins PS3, Xbox 360 16+ Battalion Wars 2 Wii T Battle Chasers: Nightwar PS4, XboxOne T Beyond Good & Evil PS2 T Big Beach Sports Wii E Bit Trip Complete Wii E Bladestorm: The Hundred Years' War PS3, Xbox 360 T Bloodstained Ritual of the Night PS4, XboxOne T Blue Dragon Xbox 360 T Blur PS3, Xbox 360 T Boom Blox Wii E Brave PS3, Xbox 360 E10+ Cabela's Big Game Hunter PS2 T Call of Duty 3 Wii T Captain America, Super Soldier PS3 T Crash Bandicoot N Sane Trilogy PS4 E10+ Crew 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dance Central 3 Xbox 360 T De Blob 2 Xbox 360 E Dead Cells PS4 T Deadly Creatures Wii T Deca Sports 3 Wii E Deformers: Ready at Dawn PS4, XboxOne E10+ Destiny PS3, Xbox 360 T Destiny 2 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt 4 PS4, XboxOne T Dirt Rally 2.0 PS4, XboxOne E Donkey Kong Country Returns Wii E Don't Starve Mega Pack PS4, XboxOne T Dragon Quest 11 PS4 T Highland Township Public Library - Video Game Collection Updated January 2020 Game Console Rating Dragon Quest Builders PS4 E10+ Dragon -

10 Minimum Towards Pokemon & Star Wars

$10 MINIMUM TOWARDS POKEMON & STAR WARS Games Eligible for this Promotion - Last Updated 11/13/19 Game .HACK G.U. LAST RECODE PS4 3D BILLARDS & SNOOKER PS4 3D MINI GOLF PS4 7 DAYS TO DIE PS4 7 DAYS TO DIE XB1 7th DRAGON III CODE VFD 3DS 8 TO GLORY PS4 8 TO GLORY XB1 8-BIT ARMIES COLLECTOR ED P 8-BIT ARMIES COLLECTORS XB1 8-BIT HORDES PS4 8-BIT INVADERS PS4 A WAY OUT PS4 A WAY OUT XB1 ABZU PS4 ABZU XB1 AC EZIO COLLECTION PS4 AC EZIO COLLECTION XB1 AC ROGUE ONE PS4 ACE COMBAT 3DS ACES OF LUFTWAFFE NSW ACES OF LUFTWAFFE PS4 ACES OF LUFTWAFFE XB1 ADR1FT PS4 ADR1FT XB1 ADV TM PRTS OF ENCHIRIDION ADV TM PRTS OF ENCHIRIDION ADV TM PRTS OF ENCHIRIDION ADVENTURE TIME 3 3DS ADVENTURE TIME 3DS ADVENTURE TIME EXP TD 3DS ADVENTURE TIME FJ INVT 3DS ADVENTURE TIME FJ INVT PS4 ADVENTURE TIME INVESTIG XB1 AEGIS OF EARTH PRO ASSAULT AEGIS OF EARTH: PROTO PS4 AEREA COLLECTORS PS4 AGATHA CHRISTIE ABC MUR XB1 AGATHA CHRSTIE: ABC MRD PS4 AGONY PS4 AGONY XB1 Some Restrictions Apply. This is only a guide. Trade values are constantly changing. Please consult your local EB Games for the most updated trade values. $10 MINIMUM TOWARDS POKEMON & STAR WARS Games Eligible for this Promotion - Last Updated 11/13/19 Game AIR CONFLICTS 2-PACK PS4 AIR CONFLICTS PACFC CRS PS4 AIR CONFLICTS SECRT WAR PS4 AIR CONFLICTS VIETNAM PS4 AIRPORT SIMULATOR NSW AKIBAS BEAT PS4 AKIBAS BEAT PSV ALEKHINES GUN PS4 ALEKHINE'S GUN XB1 ALIEN ISOLATION PS4 ALIEN ISOLATION XB1 AMAZING SPIDERMAN 2 3DS AMAZING SPIDERMAN 2 PS4 AMAZING SPIDERMAN 2 XB1 AMAZING SPIDERMAN 3DS AMAZING SPIDERMAN PSV -

Slugmag.Com 1

slugmag.com 1 SaltLakeUnderGround • Vol. 25 • Issue #311 • November 2014 • slugmag.com Publisher: Eighteen Percent Gray Marketing Coordinator: CONTRIBUTOR LIMELIGHT: Editor: Angela H. Brown Robin Sessions Managing Editor: Alexander Ortega Marketing Team: Alex Topolewski, Carl Acheson, Alex Springer Junior Editor: Christian Schultz Cassie Anderson, Cassandra Loveless, Ischa B., Janie Senior Staff Writer Office Coordinator:Gavin Sheehan Greenberg, Jono Martinez, Kendal Gillett, Lindsay Digital Content Coordinator: Henry Glasheen Clark, Raffi Shahinian, Robin Sessions, Zac Freeman Fact Checker: Henry Glasheen Social Media Coordinator: Catie Weimer Copy Editing Team: Alex Cragun, Alexander Distribution Manager: Eric Granato Ortega, Allison Shephard, Christian Schultz, Cody Distro: Andrea Silva, Daniel Alexander, Eric Kirkland, Henry Glasheen, John Ford, Jordan Granato, John Ford, Jordan Deveraux, Julia Sachs, Deveraux, Julia Sachs, Laikwan Waigwa-Stone, Maria Valenzuela, Michael Sanchez, Nancy Maria Valenzuela, Mary E. Duncan, Shawn Soward, Burkhart, Nancy Perkins, Phil Cannon, Ricky Vigil, Traci Grant Ryan Worwood, Tommy Dolph, Tony Bassett, Content Consultants: Jon Christiansen, Xkot Toxsik Matt Hoenes Senior Staff Writers: Alex Springer, Alexander Cover Photo: Chad Kirkland Ortega, Ben Trentelman, Brian Kubarycz, Brinley Lead Designer: Joshua Joye Froelich, Bryer Wharton, Christian Schultz, Cody Design Team: Chad Pinckney, Lenny Riccardi, Hudson, Cody Kirkland, Dean O. Hillis, Gavin Mason Rodrickc, Paul Mason Sheehan, Henry Glasheen, Ischa -

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Santa Cruz UC Santa Cruz Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Increasing Authorial Leverage in Generative Narrative Systems Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4dq8w2g9 Author Garbe, Jacob Publication Date 2020 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ INCREASING AUTHORIAL LEVERAGE IN GENERATIVE NARRATIVE SYSTEMS A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in COMPUTER SCIENCE by Jacob Garbe September 2020 The Dissertation of Jacob Garbe is approved: Professor Michael Mateas, Chair Professor Noah Wardrip-Fruin Professor Ian Horswill Quentin Williams Acting Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright c by Jacob Garbe 2020 Table of Contents List of Figures v Abstract xi Dedication xiii Acknowledgments xiv 1 Introduction 1 1.0.1 Traversability . 11 1.0.2 Authorability . 16 1.0.3 MDA Framework . 25 1.0.4 System, Process, Product . 26 1.0.5 Axes of Analysis . 27 1.0.6 PC3 Framework . 28 1.0.7 Progression Model . 29 1.1 Contributions . 31 1.2 Outline . 32 2 Ice-Bound 34 2.1 Experience Challenge . 35 2.2 Related Works . 41 2.2.1 Non-Digital Combinatorial Fiction . 41 2.2.2 Digital Combinatorial Fiction . 51 2.3 Relationship to Related Works . 65 2.4 System Description . 66 2.4.1 Summary . 66 2.5 The Question of Authorial Leverage . 78 2.5.1 Traversability . 78 2.5.2 Authorability . 85 2.6 System Summary .