Interracial Methodism in New Orleans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

United Methodist Bishops Page 17 Historical Statement Page 25 Methodism in Northern Europe & Eurasia Page 37

THE NORTHERN EUROPE & EURASIA BOOK of DISCIPLINE OF THE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 2009 Copyright © 2009 The United Methodist Church in Northern Europe & Eurasia. All rights reserved. United Methodist churches and other official United Methodist bodies may reproduce up to 1,000 words from this publication, provided the following notice appears with the excerpted material: “From The Northern Europe & Eurasia Book of Discipline of The United Methodist Church—2009. Copyright © 2009 by The United Method- ist Church in Northern Europe & Eurasia. Used by permission.” Requests for quotations that exceed 1,000 words should be addressed to the Bishop’s Office, Copenhagen. Scripture quotations, unless otherwise noted, are from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible, copyright © 1989 by the Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the USA. Used by permission. Name of the original edition: “The Book of Discipline of The United Methodist Church 2008”. Copyright © 2008 by The United Methodist Publishing House Adapted by the 2009 Northern Europe & Eurasia Central Conference in Strandby, Denmark. An asterisc (*) indicates an adaption in the paragraph or subparagraph made by the central conference. ISBN 82-8100-005-8 2 PREFACE TO THE NORTHERN EUROPE & EURASIA EDITION There is an ongoing conversation in our church internationally about the bound- aries for the adaptations of the Book of Discipline, which a central conference can make (See ¶ 543.7), and what principles it has to follow when editing the Ameri- can text (See ¶ 543.16). The Northern Europe and Eurasia Central Conference 2009 adopted the following principles. The examples show how they have been implemented in this edition. -

The Objects of Life in Central Africa Afrika-Studiecentrum Series

The Objects of Life in Central Africa Afrika-Studiecentrum Series Editorial Board Dr Piet Konings (African Studies Centre, Leiden) Dr Paul Mathieu (FAO-SDAA, Rome) Prof. Deborah Posel (University of Cape Town) Prof. Nicolas van de Walle (Cornell University, USA) Dr Ruth Watson (Clare College, Cambridge) VOLUME 30 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/asc The Objects of Life in Central Africa The History of Consumption and Social Change, 1840–1980 Edited by Robert Ross Marja Hinfelaar Iva Peša LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 Cover illustration: Returning to village, Livingstone, Photograph by M.J. Morris, Leya, 1933 (Source: Livingstone Museum). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The objects of life in Central Africa : the history of consumption and social change, 1840-1980 / edited by Robert Ross, Marja Hinfelaar and Iva Pesa. pages cm. -- (Afrika-studiecentrum series ; volume 30) Includes index. ISBN 978-90-04-25490-9 (pbk. : alk. paper) -- ISBN 978-90-04-25624-8 (e-book) 1. Material culture-- Africa, Central. 2. Economic anthropology--Africa, Central. 3. Africa, Central--Commerce--History. 4. Africa, Central--History I. Ross, Robert, 1949 July 26- II. Hinfelaar, Marja. III. Pesa, Iva. GN652.5.O24 2013 306.3--dc23 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 1570-9310 ISBN 978-90-04-25490-9 (paperback) ISBN 978-90-04-25624-8 (e-book) Copyright 2013 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

The Book of Discipline

THE BOOK OF DISCIPLINE OF THE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH “The Book Editor, the Secretary of the General Conference, the Publisher of The United Methodist Church and the Committee on Correlation and Editorial Revision shall be charged with edit- ing the Book of Discipline. The editors, in the exercise of their judgment, shall have the authority to make changes in wording as may be necessary to harmonize legislation without changing its substance. The editors, in consultation with the Judicial Coun- cil, shall also have authority to delete provisions of the Book of Discipline that have been ruled unconstitutional by the Judicial Council.” — Plan of Organization and Rules of Order of the General Confer- ence, 2016 See Judicial Council Decision 96, which declares the Discipline to be a book of law. Errata can be found at Cokesbury.com, word search for Errata. L. Fitzgerald Reist Secretary of the General Conference Brian K. Milford President and Publisher Book Editor of The United Methodist Church Brian O. Sigmon Managing Editor The Committee on Correlation and Editorial Revision Naomi G. Bartle, Co-chair Robert Burkhart, Co-chair Maidstone Mulenga, Secretary Melissa Drake Paul Fleck Karen Ristine Dianne Wilkinson Brian Williams Alternates: Susan Hunn Beth Rambikur THE BOOK OF DISCIPLINE OF THE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH 2016 The United Methodist Publishing House Nashville, Tennessee Copyright © 2016 The United Methodist Publishing House. All rights reserved. United Methodist churches and other official United Methodist bodies may re- produce up to 1,000 words from this publication, provided the following notice appears with the excerpted material: “From The Book of Discipline of The United Methodist Church—2016. -

The General Conferences of the Methodist Episcopal Church, From

fi-.-ii&mmwii mmmm 1 3Xmi (L17 Cx.a:<t4tt Biialicol In-diivte itt e^>LC Icvawqe,. 1 The date shows when this volume was taken. To renew this book copy the call No. and give to the hbrarian. HOME USE RULES All Books subject to Recall All borrowers must regis- ter in the library to borrow books for home use. All books must be re- turned at end of college year for inspection and repairs. ' Limited books must be re- turned within the four week limit and not renewed. Students must return all books before leaving town. OfHcers should arrange for the return of books wanted during their absence from town. Volumes of periodicals and of pamphlets are held in the library as much as possible. For special pur- poses they are given out fox a limited time. Borrowers should not use their library privileges for the benefit of other persons. Books of 'spedal value and gift books.^hen the giver wishes it, are not allowed to circulate. !^eaders are asked to re- port all cases of books, marked or mutilated.' Do not deface book! by marks and writiac. — 3 1924 oljn 029 471 1( Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924029471103 : THE General Conferences OF THE METHODIST EPISCOPAL CPIURCH FROM 1792 TO 1896. PREPARED BY A LITERARY STAFF UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF REV. LEWIS CURTS, D. D., PUBLISHING AGENT OF THE WESTERN METHODIST BOOK CONCERN. -

The United Methodist Story in Its Heritage Landmarks

Methodist History, 53:2 (January 2015) “LOOK TO THE ROCK FROM WHICH YOU WERE HEWN . .”: THE UNITED METHODIST STORY IN ITS HERITAGE LANDMARKS By action of the 2012 General Conference, there are currently forty-six Heritage Landmarks of The United Methodist Church. Five new Heritage Landmarks were designated by the General Conference with three outside the United States. These are in the Philippines, Zimbabwe, and Liberia. The Book of Discipline defines a Heritage Landmark as “a building, location, or structure specifically related to significant events, developments, or personalities in the overall history of The United Methodist Church or its antecedents.” The Heritage Landmarks of United Methodism remind us of those people and events that have shaped our history. They are tangible reminders of our heritage and their preservation helps keep our denominational legacy alive. The essay below is an excerpt from a publication created by the General Commission on Archives and History of The United Methodist Church and titled A Traveler’s Guide to the Heritage Landmarks of The United Methodist Church. While the excerpt below is only the introduction and is followed by highlights of the five newest Heritage Landmarks, the entire publication may be accessed on the website, www.gcah.org. The Wesleys in America Friday, February 6, 1736. About eight in the morning we first set foot on American ground. It was a small, uninhabited island, over against Tybee. Mr. Oglethorpe led us to a rising ground, where we all kneeled down to give thanks. So John Wesley records his arrival on American soil. Today a marker on Cockspur Island commemorates that event. -

Rhodesiana Volume 28

PUBLICATION No. 28 JULY, 1973 ~ ,,/ ' //.... · u { . ... I U' ----,,. 1896 THE STANDARD BANK LIMITED, BULAWAYO 1914 Albert Giese (i11 chair) discorere<i coal at Wankie a11d pegged a total of400 1,quare miles of coal claims in 1895. There have been changes at Wankie since 1he days of Albert Giese. Today, Wankic is more than a colliery. II is a self-contained nuning enterprise in arid northern Matabelcland. The Colliery, no1\ almos1 a Rhod~ian in-.titution, supports Rhodesia's economy to the full. Commerce, industry. tr-.im,porl and agriculture all depend on Wankie for essential supplies of coal, coke and many by-products. Coal generates po11cr, cures tobacco. smelts the country's me1als and even cooks food. Wankfo con1inues to play an important role in Rhodesia's history. The $8 million coke 01·e11 complex w!,ic!, 1ras officially opened in December, 1971, by President D11po11/. GUIDE TO THE HISTORICAL MANUSCRIPTS IN THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES OF RHODESIA by T. W. Baxter and E. E. Burke Pages: xxxiv+527; 24,1 cm x 15,9 cm. $8 The Guide describes the various record groups, highlights outstanding docu ments, as well as provides a biographical Fairbridge 1885 - 1924 sketch or introductory note on the person or body that created or owned the papers. The primary aim of the Guide is to make known to research workers the richness of the contents and scope of the Collection of Historical Manuscripts in Leask 1839 - 1912 the National Archives of Rhodesia. The Guide will also appeal to all those who are interested in the story of Rhodesia and, in particular, to collec tors of Rhodesiana and Africana. -

Heritage Landmarks: a Traveler's Guide to the Most Sacred Places Of

Heritage Landmarks: A Traveler’s Guide to the Most Sacred Places of The United Methodist Church General Commission on Archives and History P.O. Box 127, Madison, NJ 07940 2016 By action of the 2016 General Conference, there are currently forty-nine Heritage Landmarks of The United Methodist Church. The Book of Discipline defines a Heritage Landmark as “a building, location, or structure specifically related to significant events, developments, or personalities in the overall history of The United Methodist Church or its antecedents.” The Heritage Landmarks of United Methodism remind us of those people and events that have shaped our history. They are tangible reminders of our heritage and their preservation helps keep our denominational legacy alive. For further information about the forty-nine Heritage Landmarks or to learn how a place becomes so designated, please contact the General Secretary, General Commission on Archives and History, P.O. Box 127, Madison, NJ 07940. Material in this guide may be copied by local churches, Heritage Landmarks, and other agencies of The United Methodist Church without further approval. ISBN no. 1-880927-19-5 General Commission on Archives and History P.O. Box 127, 36 Madison Ave. Madison, NJ 07940 ©2016 Heritage Landmarks: A Traveler’s Guide to the Most Sacred Places in The United Methodist Church TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction: 1-9 Look to the rock from which you were hewn... The United Methodist Story in its Heritage Landmarks Heritage Landmarks: 10-107 ALABAMA 10-11 Asbury Manual Labor School/Mission, Fort Mitchell 10-11 DELAWARE 12-13 Barratt's Chapel and Museum, Frederica 12-13 FLORIDA 14-15 Bethune-Cookman University/Foundation, Daytona Beach 14-15 GEORGIA 16-23 Town of Oxford, Oxford 16-17 John Wesley's American Parish, Savannah 18-19 St. -

2016 February Current

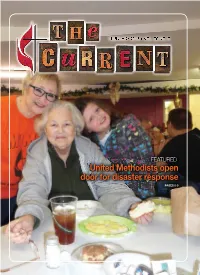

FEBRUARY 2016 • VOL. 20 NO. 8 FEATURED: United Methodists open door for disaster response PAGES 8-9 INSIDE 9 THIS ISSUE News from the Episcopal Office 1 Events & Announcements 2 Christian Conversations 3 Local Church News 4-5 Higher Education 6-7 Featured Story 8-9 Apportionments 10-14 Conference News 14-17 National / Global News 18 ON THE COVER The Current (USPS 014-964) is published Send materials to: monthly by the Illinois Great Rivers Rev. Linda Vonck, pastor of 8 P.O. Box 19207, Springfield, IL 62794-9207 Conference of The UMC, 5900 South or tel. 217.529.2040 or fax 217.529.4155 Midland UMC in Kincaid, shares Second Street, Springfield, IL 62711 a moment with Lou Dees and her [email protected], website www.igrc.org granddaughter, Ali, as they eat a An individual subscription is $15 per year. Periodical postage paid at Peoria, IL, and meal at the shelter in the church’s The opinions expressed in viewpoints are additional mailing offices. those of the writers and do not necessarily basement. The village sustained POSTMASTER: Please send address reflect the views of The Current, The IGRC, changes to significant damage when the South or The UMC. Fork River overflowed its banks, The Current, Illinois Great Rivers causing damage to 30 to 40 homes Communications Team leader: Paul E. Conference, Black Team members: Kim Halusan and P.O. Box 19207, Springfield, IL 62794-9207 in this community of 1,500. Four Michele Willson deaths were reported in the area where persons attempted to drive on flooded roads and were carried away by the current. -

The History of African Missions Has Been Told Heretofore from the Perspective of White Colonialist Missionaries

Methodist History. 33:1 (October 1994) A GREAT CENTRAL MISSION THE LEGACY OF THE UNITED METHODIST CHURCH IN ZIMBABWE NATHAN GOTO The history of African Missions has been told heretofore from the perspective of white colonialist missionaries. Consequently, the data con cerning Rhodesia/Zimbabwe missions has been understood basically from the western point of view. Little data has been adequately compiled from the African perspective. This article is a segment of the larger history of that mission, told from the perspective of the indigenous Zimbabwean. The intent of this article is to lift up historical developments and the conflict over, and obstructions to, programs designed to develop indigenous leadership during the colonial period along with the time these developments took. The story begins with the unilateral decision by the European powers to carve up Africa for their convenience and benefit, a decision in which the mission movement functioned as a support mechanism for white social control and domination of the African peoples. Background: Preparing the Way for the Missionary In 1884/5 the Berlin Conference was convened to formulate rules that would govern the process of territorial annexation by the colonial powers in Africa. It was agreed that all future claims to colonies or protectorates in any part of Africa should be formally registered. Fourteen nations signed the agreement. The Conference, which affirmed the political, economic and religious alliance that existed between colonialists and missionaries- the linking of cross and crown, provided an umbrella of law and order for missionary work in Africa. Abolition of the slave trade and freedom of worship were guaranteed. -

United Methodist Bishops Ordination Chain 1784 - 2012

United Methodist Bishops Ordination Chain 1784 - 2012 General Commission on Archives and History Madison, New Jersey 2012 UNITED METHODIST BISHOPS in order of Election This is a list of all the persons who have been consecrated to the office of bishop in The United Methodist Church and its predecessor bodies (Methodist Episcopal Church; Methodist Protestant Church; Methodist Episcopal Church, South; Church of the United Brethren in Christ; Evangelical Association; United Evangelical Church; Evangelical Church; The Methodist Church; Evangelical United Brethren Church, and The United Methodist Church). The list is arranged by date of election. The first column gives the date of election; the second column gives the name of the bishop. The third column gives the name of the person or organization who ordained the bishop. The list, therefore, enables clergy to trace the episcopal chain of ordination back to Wesley, Asbury, or another person or church body. We regret that presently there are a few gaps in the ordination information, especially for United Methodist Central Conferences. However, the missing information will be provided as soon as it is available. This list was compiled by C. Faith Richardson and Robert D. Simpson . Date Elected Name Ordained Elder by 1784 Thomas Coke Church of England 1784 Francis Asbury Coke 1800 Richard Whatcoat Wesley 1800 Philip William Otterbein Reformed Church 1800 Martin Boehm Mennonite Society 1807 Jacob Albright Evangelical Association 1808 William M'Kendree Asbury 1813 Christian Newcomer Otterbein 1816 Enoch George Asbury 1816 Robert Richford Roberts Asbury 1817 Andrew Zeller Newcomer 1821 Joseph Hoffman Otterbein 1824 Joshua Soule Whatcoat 1824 Elijah Hedding Asbury 1825 Henry Kumler, Sr. -

Making Muslims: American Methodists and the Framing of Islam

1 “Making Muslims: American Methodists and the Framing of Islam” 2013 Oxford Institute of Methodist Theological Studies Wesley/Methodist Historical Studies Group Christopher J. Anderson Drew University Introduction On the afternoon of June 23, 1919 Samuel M. Zwemer, missionary to North Africa and editor of The Moslem World, stood proudly at the podium of the Centenary Celebration of American Methodist Missions in Columbus, Ohio. The Celebration exposition, a twenty-four day “Methodist World’s Fair,” attracted over one million visitors and featured internationally-themed pavilions, ethnographically-charged exhibits, the latest in church media technologies, and a miniature Midway complete with a Ferris wheel, lemonade stands, and church-sponsored restaurants. The fair was a significant endeavor planned by American Methodists from the Methodist Episcopal Church and the Methodist Episcopal Church, South. The event functioned as a location to showcase the global reach of American Methodist missionary efforts, and in particular, the religious and cultural exchanges between Christian missionaries and Muslim adherents were on display. At the exposition, several decorated pavilions dedicated to Methodist missionary activities spotlighted historical and contemporary interactions between American Methodists and global Muslims. At the fair Zwemer was in his element, speaking to an audience curious to know more about Islam and its many followers throughout the world. As a reputable American Protestant specialist on Islam Zwemer had been asked to speak of his work with Muslims on “African Day” at the Ohio exposition.1 Zwemer was introduced to the largely American Methodist audience by 1 Samuel Marinus Zwemer (1867-1952) was an American Protestant missionary sponsored by the Reformed Church of America. -

Guide to the Papers of Bishop John Mckendree Springer 1840 - 1961

Guide to the Papers of Bishop John McKendree Springer 1840 - 1961 General Commission on Archives and History of the United Methodist Church P.O. Box 127, Madison, NJ 07940 2016-12-01 Guide to the Papers of Bishop John McKendree Springer Papers of Bishop John McKendree Springer 1840 - 1961 60 Cubic feet gcah.ms.660 The items located at 2259-5-2 to 2259-6-6, 2262-4-1 to 2261-6-8, and 2267-3-1 to 2267-6-2 are a series of photographs and negatives which have not yet been arranged or described, as well as the originals of photocopied records in the collection. The photographs and negatives mentioned above are currently in white paper folders within document cases and storage boxes. They are in need of professional attention ( flattening, special storage, etc.) Biographical Note John McKendree Springer (1873-1963), a pioneering Methodist Episcopal Church missionary and bishop, was instrumental in developing Methodism in Africa. He graduated from Northwestern University (1895 and 1899) and received a Bachelor of Divinity degree from Garrett Biblical Institute (1901). In 1901 he was appointed a missionary. From 1901 to 1906 he was a pastor and the superintendent of the Old Umtali Industrial Mission in Rhodesia. During 1907 he and his wife journeyed across the continent of Africa. His first furlough was taken from 1907-1909, and when he returned to Africa in 1910, he was stationed in the Lunda country of Angola and Congo. Between 1910 and 1915 Springer had various appointments: Kalalua in North Western Rhodesia ( 1910-1911); Lukoshi in Belgian Congo (1911-1913); and Kambove (1913- 1915).