“Underconsumption” in “Global Capitalism” to the “Imperialist Chain”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

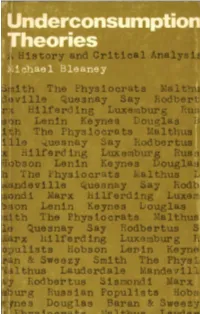

Underconsumption Theories

UNDER- CONSUMPTION THEORIES A History and Critical Analysis by M.F. Bleaney 1976 INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHERS New York Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Bleaney, Michael Francis Underconsumption theories. Bibliography. Includes index. 1. Business cycles. 2. Consumption (Economics) 3. Economics—History. I. Title. HB3721.B55 330.1 76-26935 ISBN 0-7178-0476-3 © M. F. Bleaney Produced by computer-controlled phototypesetting, using OCR input techniques, and printed offset by UNWIN BROTHERS LIMITED The Gresham Press, Old Woking, Surrey PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This book is intended as a Marxist analysis of underconsump- tion theories. It is at once a history and a critique — for underconsumption theories are by no means dead. Their influence may still be discerned in the economic programmes put forward by political parties and trade unions, and in articles and books on the general tendencies of capitalism. No final conclusion as to the correctness of underconsumption theories is reached, for too little theoretical work of the necessary quality has been carried out to justify such a conclusion. But the weight of the theoretical evidence would seem to be against them. Much of their attractiveness in the end stems from the links which they maintain with the dominant ideology of capitalist society and the restricted extent of the theoretical break required to arrive at an underconsumptionist position. This, in conjunction with certain obviously appealing conclusions which emerge from them, has sufficed to ensure their continuing reproduction in the working-class movement. Not all of the authors discussed here are in fact underconsumptionist — Karl Marx and Rosa Luxemburg, in particular, are not — but all of them have been accused of being so at one time or another. -

Moneyflows and Business Fluctuations

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: A Study of Moneyflows in the United States Volume Author/Editor: Morris A. Copeland Volume Publisher: NBER Volume ISBN: 0-87014-053-1 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/cope52-1 Publication Date: 1952 Chapter Title: Moneyflows and Business Fluctuations Chapter Author: Morris A. Copeland Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c0838 Chapter pages in book: (p. 240 - 289) Chapter 12 MONEYFLOWS AND BUSINESS FLUCTUATIONS The tumbling of prices in the panic is in large part due to the fact that the holders either of money or of deposit credit will not buy with it. Physically the money is there —asquantity, as concrete thing; psychologically, s pur- chasing power, it has vanished. So, also, the deposit credits exist, but they have ceased to exist as demand for products. They are merely hoarded, post- poned purchasing power. As present circulating medium, as present demand for anything, they are not. H. J. Davenport, The Economics of Enterprise (Macmillan, 1913), p. 318. Loan funds must be recognized as intangible and incorporeal facts, a sheer matter of intricacy and complexity in business relations —meshesof obligation —amere scaffolding of promises —afolding back one upon another of successive layers of credit. And because not necessarily represen- tative of an increase of social capital or even of the liquidated total of private capital, it seems necessary to recOgnize the loan fund as a distinct economic category. H. J. Davenport, Value and Distribution (University of Chicago Press, 1908), p. -

W. Stark, J.M. Keynes and the Mercantilists 30/09/2019

W. Stark, J.M. Keynes and the Mercantilists 30/09/2019 Constantinos Repapis1 Abstract In this paper we investigate Werner Stark’s sociology of knowledge approach in the history of economic thought. This paper explores: 1) The strengths and weaknesses of Stark’s approach to historiography, 2) seeing how this can frame an understanding of mercantilist writings and, 3) develop a link between a pluralist understanding of economics, and the sociology of knowledge approach. The reason for developing this link is to extend the sociology of knowledge approach to encompass a pluralist understanding of economic theorising and, at the same time, clarify the link between context and economic theory. John Maynard Keynes’ practice of building narratives of intellectual traditions as evidenced in The General Theory is used to develop a position between an understanding of history of economic thought as the evolution of abstract and de-contextualized economic theorising and, the view of economic theory as only relevant within the social conditions from which it arose. Keywords: Werner Stark, Mercantilism, sociology of knowledge 1 Correspondence may be addressed to: C. Repapis, Institute of Management Studies, Goldsmiths, University of London. Email: [email protected]. I would like to thank Geoff Harcourt, Sheila Dow, Ragupathy Venkatachalam, Kumaraswamy (Vela) Velupillai, Maxime Desmarais-Tremblay, Harro Maas, two anonymous referees for valuable feedback, and the participants of the 2019 ESHET session in Lille and the THETS session in Goldsmiths, for helpful comments and discussions. Finally, I would like to thank Dr. Daniele Besomi for clarifications on the Harrod-Keynes correspondence. 1 JEL Codes: B11, B31, B40 2 I. -

Business Cycles, Financial Conditions and Nonlinearities Ivan Mendieta

DEPARTMENT OF ECONOMICS WORKING PAPER SERIES Business cycles, financial conditions and nonlinearities Ivan Mendieta-Muñoz Doğuhan Sündal Working Paper No: 2020-04 May 2020 University of Utah Department of Economics 260 S. Central Campus Dr., GC. 4100 Tel: (801) 581-7481 Fax: (801) 585-5649 http://www.econ.utah.edu Business cycles, financial conditions and nonlinearities Ivan Mendieta-Muñoz Department of Economics, University of Utah [email protected] Doğuhan Sündal Department of Economics, University of Utah [email protected] Abstract This paper proposes a conceptualization of business cycle fluctuations in which the role of financial conditions and nonlinear dynamics are explicitly incorporated. We highlight the role of investment demand in driving economic fluctuations, consider its endogenous dynamic interactions with profitability and aggregate demand levels as well as financial conditions, emphasize that the sources of instability in an economy cannot be associated exclusively with the real or financial sectors, and incorporate the idea that financial conditions are both important sources of instability and possible nonlinear propagators of other sources of instability. We test the propagation mechanisms of such conceptualization using a Bayesian Threshold Vector Autoregression model for the US economy. The results support the characterization of nonlinear dynamics in the transmission of shocks since there is evidence of asymmetric responses of the variables across two different regimes of financial stress, responding more strongly during loose financial conditions. Keywords: Business cycles; investment fluctuations; financial conditions; nonlinear dynamics; Bayesian Threshold Vector Autoregression. JEL Classification: B50; E10; E22; E32; E43. 1 Introduction The study of the nature of business cycle fluctuations and of its propagation mechanisms are topics of paramount importance in order to understand short-run changes in economic activity and to provide economic policies that respond adequately to such endogenous events. -

The Place of Keynes in the History of Economic Theory

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1956 The lP ace of Keynes in the History of Economic Theory. Leon Francis Lee Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Lee, Leon Francis, "The lP ace of Keynes in the History of Economic Theory." (1956). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 150. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/150 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IKE PLACE OF KEYNES IN IKK HISTORY OF ECONOMIC THEORY A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty o‘" the. Louisiana State- University and Aqricul turn] and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirement*.! for the decree of Doctor of Fhilonophy in The Department of Economics b y ^ ./ Icon FLee B. A., University of Oklahoma. 19^0 M. A., University o*' Oklahoma, 19-^6 June, 191)6 ACK7;OTmr,xEi;? Grateful acknowledgment lc extended to the following persona for thoir many criticisms, suggestions, and valuable words of guidance ir. the preparation of this dissertation: !>. Harlan L. KeCr&ckcn, Dr. William D. Ross, Dr. Kenneth K . Thompson, Dr. John W. Chisholm, and Dr. Walter F. 3crns. Sincere appreciation is extended to my wife, Baby, who typed the final manuscript and offered sympathy and encouragement during the difficult days of the study. -

Critical Companion to Contemporary Marxism

Critical Companion to Contemporary Marxism BIDET2_f1_i-xv.indd i 10/25/2007 8:05:05 PM Historical Materialism Book Series Editorial Board Paul Blackledge, Leeds – Sébastien Budgen, Paris Michael Krätke, Amsterdam – Stathis Kouvelakis, London – Marcel van der Linden, Amsterdam China Miéville, London – Paul Reynolds, Lancashire Peter Thomas, Amsterdam VOLUME 16 BIDET2_f1_i-xv.indd ii 10/25/2007 8:05:05 PM Critical Companion to Contemporary Marxism Edited by Jacques Bidet and Stathis Kouvelakis LEIDEN • BOSTON 2008 BIDET2_f1_i-xv.indd iii 10/25/2007 8:05:05 PM This book is an English translation of Jacques Bidet and Eustache Kouvelakis, Dic- tionnaire Marx contemporain. C. Presses Universitaires de France, Paris 2001. Ouvrage publié avec le concours du Ministère français chargé de la culture – Centre national du Livre. This book has been published with financial aid of CNL (Centre National du Livre), France. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Translations by Gregory Elliott. ISSN 1570-1522 ISBN 978 90 04 14598 6 Copyright 2008 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

Marxist Theories of Imperialism: Evolution of a Concept

Marxist theories of imperialism: evolution of a concept By Murray Noonan, BA (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Communication and the Arts Faculty of Arts, Education and Human Development Victoria University September, 2010 ABSTRACT Over the course of the twentieth century and into the new millennium, critical analysis of imperialism has been a feature of Marxist thought. One of the salient concerns of Marxist theorising of imperialism has been the uncovering of the connections between the capitalist accumulation process and the political and economic domination of the world by advanced capitalist countries. The conceptualising and theorising of imperialism by Marxists has evolved in response to developments in the global capitalist economy and in international politics. For its methodological framework, this thesis employs conceptual and generational typologies, which I term the ‘generational typology of Marxist theories of imperialism’. This methodological approach is used to assess the concept of imperialism as sets of ideas with specific concerns within three distinct phases. The first phase, starting in 1902 with Hobson and finishing in 1917 with Lenin’s pamphlet, covers who I call the ‘pioneers of imperialism theory’. They identified changes to capitalism, where monopolies, financiers and finance capital and the export of capital had become prominent. The second phase of imperialism theory, the neo-Marxist phase, started with Sweezy in 1942. Neo-Marxist imperialism theory had its peak of influence in the late 1960s to early 1980s, declining in influence since. Writers in this cohort focussed on the lack of development of the peripheral countries. -

"Keynesian Economics" Wikipedia

Keynesian economics (pronounced /ˈkeɪnziən/ KAYN-zee-ən, also called Keynesianism and Keynesian theory) is a macroeconomic theory based on the ideas of 20th century British economist John Maynard Keynes. Keynesian economics argues that private sector decisions sometimes lead to inefficient macroeconomic outcomes and therefore advocates active policy responses by the public sector, including monetary policy actions by the central bank and fiscal policy actions by the government to stabilize output over the business cycle.[1] The theories forming the basis of Keynesian economics were first presented in The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, published in 1936; the interpretations of Keynes are contentious, and several schools of thought claim his legacy. Keynesian economics advocates a mixed economy—predominantly private sector, but with a large role of government and public sector—and served as the economic model during the latter part of the Great Depression, World War II, and the post-war economic expansion (1945–1973), though it lost some influence following the stagflation of the 1970s. The advent of the global financial crisis in 2007 has caused a resurgence in Keynesian thought. The former British Prime Minister Gordon Brown, former President of the United States George W. Bush[2] ( also alleged heavily being anti-Keynesian by some (The Shock Doctrine)), President of the United States Barack Obama, and other world leaders have used Keynesian economics through government stimulus programs to attempt to assist the economic state of their countries.[3] Overview According to Keynesian theory, some microeconomic-level actions—if taken collectively by a large proportion of individuals and firms—can lead to inefficient aggregate macroeconomic outcomes, where the economy operates below its potential output and growth rate. -

The Marxist Theory of Overaccumulation and Crisis

The Marxist Theory of Overaccumulation and Crisis Simon Clarke In this paper I intend to contrast the `falling rate of profit’ crisis theories of the 1970s with the `underconsumptionism' of the orthodox Marxist tradition. The central argument is that in rejecting traditional underconsumptionist theories of crisis contemporary Marxism has thrown the baby out with the bathwater, with unfortunate theoretical and political consequences. A more adequate critique of traditional underconsumptionism leads not to the falling rate of profit, but to a dis- proportionality theory of crisis, which follows the traditional theory in seeing crises not as epochal events but as expressions of the permanent tendencies of capitalist accumulation. The background to the paper is my recent book, Keynesianism, Monetarism and the Crisis of the State (Clarke, 1988a), in which analysed the development of capitalism on the basis of a version of the theory of overaccumulation and crisis which is proposed here. However in the book this theory is developed in relation to the historical analysis, without reference to either traditional or contemporary debates. The purpose of this paper is to draw out the theoretical significance of the argument as the basis of a re- evaluation of the Marxist tradition. The issue is of the highest importance as erstwhile Marxists, in both East and West, fall victim once more to the `reformist illusion' that the negative aspects of capitalism can be separated from the positive, that the dynamism of capitalism can be separated from its crisis tendencies, that capitalist prosperity can be separated from capitalist immiseration. 1 Contemporary Marxist Crisis Theory The Marxist theory of crisis is distinguished from bourgeois theories in the first instance in being concerned with the necessity of crisis, in order to establish that the permanent stabilisation of capitalism and amelioration of the class struggle, on which reformism pins its hopes, is impossible. -

John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes Hyman P. Minsky New York Chicago San Francisco Lisbon London Madrid Mexico City Milan New Delhi San Juan Seoul Singapore Sydney Toronto For more information about this title, click here contents Preface by Robert J. Barbera vii Introduction by Dimitri B. Papadimitriou and L. Randall Wray xi 1. THE GENERAL THEORY AND ITS INTERPRETATION 1 2. THE CONVENTIONAL WISDOM: THE STANDARD INTERPRETATION OF KEYNES 19 3. FUNDAMENTAL PERSPECTIVES 53 4. CAPITALIST FINANCE AND THE PRICING OF CAPITAL ASSETS 67 5. THE THEORY OF INVESTMENT 91 6. FINANCIAL INSTITUTIONS, FINANCIAL INSTABILITY, AND THE PACE OF INVESTMENT 115 7. SOME IMPLICATIONS OF THE ALTERNATIVE INTERPRETATION 129 8. SOCIAL PHILOSOPHY AND ECONOMIC POLICY 143 9. POLICY IMPLICATIONS OF THE ALTERNATIVE INTERPRETATION 159 Bibliography 167 Index 169 v preface T he missing step in the standard Keynesian theory [is] the explicit considera- tion of capitalist finance within a cyclical and speculative context . finance sets the pace for the economy. As recovery approaches full employment . soothsayers will proclaim that the business cycle has been banished [and] debts can be taken on...But in truth neither the boom, nor the debt deflation...and certainly not a recovery can go on forever. Each state nurtures forces that lead to its own destruction. So wrote Hyman Minsky some thirty years ago. As Minsky sketched out this reinterpretation of The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, mainstream economics was in the midst of rejecting much of the Keynesian thesis that had dominated thinking in the early postwar years. The new wave in academia swung backward, returning to classical economic conceits that embraced the infallibility of markets. -

Is Germany a Mercantilist State? the Dispute Over Trade Between Berlin and Washington Under Merkel and Trump Pierre Baudry

Is Germany a mercantilist state? The dispute over trade between Berlin and Washington under Merkel and Trump Pierre Baudry To cite this version: Pierre Baudry. Is Germany a mercantilist state? The dispute over trade between Berlin and Wash- ington under Merkel and Trump. international studies association, Apr 2019, Toronto, Canada. hal- 02105531v1 HAL Id: hal-02105531 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02105531v1 Submitted on 21 Apr 2019 (v1), last revised 6 May 2019 (v2) HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Copyright Is Germany a mercantilist state? The dispute over trade between Berlin and Washington under Merkel and Trump Pierre Baudry 2019 © Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes/CNRS, PSL, France Email: [email protected] Pierre Baudry teaches at the University of Tours (France). He is finishing his Ph.D. at the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes/CNRS, PSL. His Ph.D. is about the European policy of the Christian-democratic parties, CDU/CSU, under Angela Merkel from 1998 to 2016. He focuses Berlin’s policy during the euro and the migrant crisis and the tensions between the USA and Germany since Trump’s election. -

The Economies' Cyclical Behaviour After Wwii

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE THE ECONOMIES’ CYCLICAL BEHAVIOUR AFTER WWII How Do Crises of Underconsumption and Overproduction Arise? Like other Marxist theoretical models, also capitalist overproduc- tion of goods must be interpreted in terms of values and not merely of physical quantities of produced goods. Th e permanent struggle between rival capitals involves the development of competitive tech- nologies that permit higher productivity, higher profi ts and greater production of goods. However, the goods, under capitalism, are pro- duced only if they are sold in the market. Th ey enable the closure of the cycle of capital (re) production, enhancement of the capital, the reali- zation of exchange value. A commodity is not produced just because someone needs it (this identifi es only the use value), but because someone who needs it, can buy it, and thus allows the realization of its intrinsic value. On several occasions Marx, ahead of his own time, criticized these theories. Th e problem has no solution because the temporary increase in demand, supported by the State in various capacities and in diff erent ways, moves in time, postponing overproduction and repeating it at a higher and sharper level. Th is is because the temporary valorization of commodities does not stabilize the market at determined production quotas (we should only imagine a stagnation). Instead it stimulates the productive sphere to produce more goods than before. Th e crisis of overproduction cannot be eliminated because it is inherent to capitalist production, where capital always pushes beyond the latest (temporary) limit to increase itself. Th is means more com- modities, more capital and the inability to close the cycle of capital (re) production positively.