The Place of Keynes in the History of Economic Theory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Syllabus Economics 341 American Economic History Spring 2017

Syllabus Economics 341 American Economic History Spring 2017 – Blow Hall 331 Prof. Will Hausman Economics 341 is a one-semester survey of the development of the U.S. economy from colonial times to the outbreak of World War II. The course uses basic economic concepts to help describe and explain overall economic growth as well as developments in specific sectors or aspects of the economy, such as agriculture, transportation, industry and commerce, money and banking, and public policy. The course focuses on events, trends, and institutions that fostered or hindered the economic development of the nation. At the end of the course, you should have a better understanding of the antecedents of our current economic situation. The course satisfies GER 4-A and the Major Writing Requirement. Blackboard: announcements, assignments, documents, links, data, and power points will be posted on Blackboard. Importantly, emails will be sent to the class through Blackboard. Text and Readings: There is a substantial amount of reading in this course. The recommended text is Gary Walton and Hugh Rockoff, History of the American Economy (any edition 7th through 12th; publication dates, 1996-2015). This is widely available under $10 in on-line used bookstores; I personally use the 8th edition (1998). This will be used mostly for background information. There also will be articles or book chapters assigned every week, as well as original documents. I expect you to read all articles and documents thoroughly and carefully. These will all be available on Blackboard, or can be found directly on JSTOR (via the Database Links on the Swem Library home page), or the journal publisher’s home page via Swem’s online catalog. -

Uncertainty and Hyperinflation: European Inflation Dynamics After World War I

FEDERAL RESERVE BANK OF SAN FRANCISCO WORKING PAPER SERIES Uncertainty and Hyperinflation: European Inflation Dynamics after World War I Jose A. Lopez Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Kris James Mitchener Santa Clara University CAGE, CEPR, CES-ifo & NBER June 2018 Working Paper 2018-06 https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/working-papers/2018/06/ Suggested citation: Lopez, Jose A., Kris James Mitchener. 2018. “Uncertainty and Hyperinflation: European Inflation Dynamics after World War I,” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Working Paper 2018-06. https://doi.org/10.24148/wp2018-06 The views in this paper are solely the responsibility of the authors and should not be interpreted as reflecting the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco or the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. Uncertainty and Hyperinflation: European Inflation Dynamics after World War I Jose A. Lopez Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Kris James Mitchener Santa Clara University CAGE, CEPR, CES-ifo & NBER* May 9, 2018 ABSTRACT. Fiscal deficits, elevated debt-to-GDP ratios, and high inflation rates suggest hyperinflation could have potentially emerged in many European countries after World War I. We demonstrate that economic policy uncertainty was instrumental in pushing a subset of European countries into hyperinflation shortly after the end of the war. Germany, Austria, Poland, and Hungary (GAPH) suffered from frequent uncertainty shocks – and correspondingly high levels of uncertainty – caused by protracted political negotiations over reparations payments, the apportionment of the Austro-Hungarian debt, and border disputes. In contrast, other European countries exhibited lower levels of measured uncertainty between 1919 and 1925, allowing them more capacity with which to implement credible commitments to their fiscal and monetary policies. -

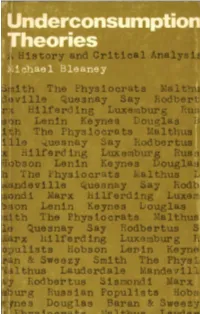

Underconsumption Theories

UNDER- CONSUMPTION THEORIES A History and Critical Analysis by M.F. Bleaney 1976 INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHERS New York Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Bleaney, Michael Francis Underconsumption theories. Bibliography. Includes index. 1. Business cycles. 2. Consumption (Economics) 3. Economics—History. I. Title. HB3721.B55 330.1 76-26935 ISBN 0-7178-0476-3 © M. F. Bleaney Produced by computer-controlled phototypesetting, using OCR input techniques, and printed offset by UNWIN BROTHERS LIMITED The Gresham Press, Old Woking, Surrey PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This book is intended as a Marxist analysis of underconsump- tion theories. It is at once a history and a critique — for underconsumption theories are by no means dead. Their influence may still be discerned in the economic programmes put forward by political parties and trade unions, and in articles and books on the general tendencies of capitalism. No final conclusion as to the correctness of underconsumption theories is reached, for too little theoretical work of the necessary quality has been carried out to justify such a conclusion. But the weight of the theoretical evidence would seem to be against them. Much of their attractiveness in the end stems from the links which they maintain with the dominant ideology of capitalist society and the restricted extent of the theoretical break required to arrive at an underconsumptionist position. This, in conjunction with certain obviously appealing conclusions which emerge from them, has sufficed to ensure their continuing reproduction in the working-class movement. Not all of the authors discussed here are in fact underconsumptionist — Karl Marx and Rosa Luxemburg, in particular, are not — but all of them have been accused of being so at one time or another. -

Moneyflows and Business Fluctuations

This PDF is a selection from an out-of-print volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: A Study of Moneyflows in the United States Volume Author/Editor: Morris A. Copeland Volume Publisher: NBER Volume ISBN: 0-87014-053-1 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/cope52-1 Publication Date: 1952 Chapter Title: Moneyflows and Business Fluctuations Chapter Author: Morris A. Copeland Chapter URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c0838 Chapter pages in book: (p. 240 - 289) Chapter 12 MONEYFLOWS AND BUSINESS FLUCTUATIONS The tumbling of prices in the panic is in large part due to the fact that the holders either of money or of deposit credit will not buy with it. Physically the money is there —asquantity, as concrete thing; psychologically, s pur- chasing power, it has vanished. So, also, the deposit credits exist, but they have ceased to exist as demand for products. They are merely hoarded, post- poned purchasing power. As present circulating medium, as present demand for anything, they are not. H. J. Davenport, The Economics of Enterprise (Macmillan, 1913), p. 318. Loan funds must be recognized as intangible and incorporeal facts, a sheer matter of intricacy and complexity in business relations —meshesof obligation —amere scaffolding of promises —afolding back one upon another of successive layers of credit. And because not necessarily represen- tative of an increase of social capital or even of the liquidated total of private capital, it seems necessary to recOgnize the loan fund as a distinct economic category. H. J. Davenport, Value and Distribution (University of Chicago Press, 1908), p. -

Complementary Currencies: Mutual Credit Currency Systems and the Challenge of Globalization

Complementary Currencies: Mutual Credit Currency Systems and the Challenge of Globalization Clare Lascelles1 Abstract Complementary currencies—currencies operating alongside the official currency—have taken many forms throughout the last century or so. While their existence has a rich history, complementary currencies are increasingly viewed as anachronistic in a world where the forces of globalization promote further integration between economies and societies. Even so, towns across the globe have recently witnessed the introduction of complementary currencies in their region, which connotes a renewed emphasis on local identity. This paper explores the rationale behind the modern-day adoption of complementary currencies in a globalized system. I. Introduction Coined money has two sides: heads and tails. ‘Heads’ represents the state authority that issued the coin, while ‘tails’ displays the value of the coin as a medium of exchange. This duality—the “product of social organization both from the top down (‘states’) and from the bottom up (‘markets’)”—reveals the coin as “both a token of authority and a commodity with a price” (Hart, 1986). Yet, even as side ‘heads’ reminds us of the central authority that underwrote the coin, currency can exist outside state control. Indeed, as globalization exerts pressure toward financial integration, complementary currencies—currencies existing alongside the official currency—have become common in small towns and regions. This paper examines the rationale behind complementary currencies, with a focus on mutual credit currency, and concludes that the modern-day adoption of complementary currencies can be attributed to the depersonalizing force of globalization. II. Literature Review Money is certainly not a topic unstudied. -

Markets Not Capitalism Explores the Gap Between Radically Freed Markets and the Capitalist-Controlled Markets That Prevail Today

individualist anarchism against bosses, inequality, corporate power, and structural poverty Edited by Gary Chartier & Charles W. Johnson Individualist anarchists believe in mutual exchange, not economic privilege. They believe in freed markets, not capitalism. They defend a distinctive response to the challenges of ending global capitalism and achieving social justice: eliminate the political privileges that prop up capitalists. Massive concentrations of wealth, rigid economic hierarchies, and unsustainable modes of production are not the results of the market form, but of markets deformed and rigged by a network of state-secured controls and privileges to the business class. Markets Not Capitalism explores the gap between radically freed markets and the capitalist-controlled markets that prevail today. It explains how liberating market exchange from state capitalist privilege can abolish structural poverty, help working people take control over the conditions of their labor, and redistribute wealth and social power. Featuring discussions of socialism, capitalism, markets, ownership, labor struggle, grassroots privatization, intellectual property, health care, racism, sexism, and environmental issues, this unique collection brings together classic essays by Cleyre, and such contemporary innovators as Kevin Carson and Roderick Long. It introduces an eye-opening approach to radical social thought, rooted equally in libertarian socialism and market anarchism. “We on the left need a good shake to get us thinking, and these arguments for market anarchism do the job in lively and thoughtful fashion.” – Alexander Cockburn, editor and publisher, Counterpunch “Anarchy is not chaos; nor is it violence. This rich and provocative gathering of essays by anarchists past and present imagines society unburdened by state, markets un-warped by capitalism. -

Free Money of Wörgl & Complementary Currencies

Summer School for Alternative Economic and Monetary Systems Free Money of Wörgl & Complementary Currencies Vienna, July 24th, 2015 Speaker: Heinz Hafner & Veronika Spielbichler Unterguggenberger Institute, Wörgl is a registered non-profit society, founded in 2003 for the documentation and public education on the WWII free money experiment in Wörgl as well as for contemporary research on complementary currencies nowadays. The Unterguggenberger Institute initiated the „LA21 youth project I-MOTION“ in 2004. The society is a founding member of the initiative „Neues Geld in Österreich 2007“ and addressed a petition onto the Austrian Parliament in 2008. unterguggenberger.org archiv.unterguggenberger.org neuesgeld.com Money for the Freedom of Creation • PART I ~15min impuls from the past Free Money of Wörgl („Wörgler Freigeld“) an historic show case • PART II ~15min impuls from the present complementary currencies today options & experiments (flattering & colourful) • PART III ~60min impuls for the future an interactive approach to currency design classification sheet drafting PART #1 – impuls from the past The monetary experiment in Wörgl – Wörgls Free Money a short outline on a historic show case Initial situation: the historic economic situation in the region of Wörgl The driver: Mayor Michael Unterguggenberger – his life Prearrangements of the Free Money experiment: - foundation of the Free Economic Group of Wörgl - political decisions within the municipality Realization: creation of a demurrage voucher, which represented the worth of labour time – monthly charge in the form of stamps that needed to be bought and sticked onto the voucher – construction programme – facilitation of consumption – fostering municipal taxes – creation of an infinite cycle After life of the experiment: Imitations and copycats in Austria, international attention by the media Between 1900 and 1930 the small town of Wörgl Develops as an industrial and commercial center due to its convenient location mainly based on the railway infrastructure. -

Engineering Economy for Economists

AC 2008-2866: ENGINEERING ECONOMY FOR ECONOMISTS Peter Boerger, Engineering Economic Associates, LLC Peter Boerger is an independent consultant specializing in solving problems that incorporate both technological and economic aspects. He has worked and published for over 20 years on the interface between engineering, economics and public policy. His education began with an undergraduate degree in Mechanical Engineering from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, adding a Master of Science degree in a program of Technology and Public Policy from Purdue University and a Ph.D. in Engineering Economics from the School of Industrial Engineering at Purdue University. His firm, Engineering Economic Associates, is located in Indianapolis, IN. Page 13.503.1 Page © American Society for Engineering Education, 2008 Engineering Economy for Economists 1. Abstract The purpose of engineering economics is generally accepted to be helping engineers (and others) to make decisions regarding capital investment decisions. A less recognized but potentially fruitful purpose is to help economists better understand the workings of the economy by providing an engineering (as opposed to econometric) view of the underlying workings of the economy. This paper provides a review of some literature related to this topic and some thoughts on moving forward in this area. 2. Introduction Engineering economy is inherently an interdisciplinary field, sitting, as the name implies, between engineering and some aspect of economics. One has only to look at the range of academic departments represented by contributors to The Engineering Economist to see the many fields with which engineering economy already relates. As with other interdisciplinary fields, engineering economy has the promise of huge advancements and the risk of not having a well-defined “home base”—the risk of losing resources during hard times in competition with other academic departments/specialties within the same department. -

IJCCR 2015 Rosa Stodder

International Journal of Community Currency Research VOLUME 19 (2015) SECTION D 114-127 ON VELOCITY IN SEVERAL COMPLEMENTARY CURRENCIES Josep Lluis De La Rosa* And James Stodder** *TECNIO Centre EASY, University Of Girona, Catalonia ** Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, USA ABSTRACT We analyse the velocity of several complementary currencies, notably the WIR, RES, Chiem- gauer, Sol, Berkshares dollars, and several other cases. Then we describe the diversity in their velocity of circulation, and seek potential explanations for these differences. For example, WIR velocity is 2.6 while RES velocity is 1.9 despite being similar currencies. The higher speed may be explained by WIR blended loans among other beneIits or by the fact that there are nearly 20.000 unregistered members that contribute with their transactions. Using a comparative method between cases, the article explores a number of possible explanations on the increases in velocity, apart from prevailing demurrage approaches ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I want to thank the several reviewers of this paper, especially Andreu Honzawa of the STRO foundation. This research is partly funded by the TIN2013-48040-R (QWAVES) Nuevos méto- dos de automatización de la búsqueda social basados en waves de preguntas, the IPT20120482430000 (MIDPOINT) Nuevos enfoques de preservación digital con mejor gestión de costes que garantizan su sostenibilidad, and VISUAL AD Uso de la Red Social para Monetizar el Contenido Visual, RTC-2014-2566-7 and GEPID GamiIicación en la Preservación Digital de- splegada sobre las Redes Sociales, RTC-2014-2576-7, the EU DURAFILE num. 605356, FP7- SME-2013, BSG-SME (Research for SMEs) Innovative Digital Preservation using Social Search in Agent Environments, as well as the AGAUR 2012 FI_B00927 awarded to José Antonio Olvera and the Grup de recerca consolidat CSI-ref. -

The History of Economic Inequality in Illinois

The History of Economic Inequality in Illinois 1850 – 2014 March 4, 2016 Frank Manzo IV, M.P.P. Policy Director Illinois Economic Policy Institute www.illinoisepi.org The History of Economic Inequality in Illinois EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This Illinois Economic Policy Institute study is the first ever historical analysis of economic inequality in Illinois. Illinois blossomed from a small agricultural economy into the transportation, manufacturing, and financial hub of the Midwest. Illinois has had a history of sustained population growth. Since 2000, the state’s population has grown by over 460,000 individuals. As of 2014, 63 percent of Illinois’ population resides in a metropolitan area and 24 percent have a bachelor’s degree or more – both historical highs. The share of Illinois’ population that is working has increased over time. Today, 66 percent of Illinois’ residents are in the labor force, up from 57 percent just five decades ago. Employment in Illinois has shifted, however, to a service economy. While one-third of the state’s workforce was in manufacturing in 1950, the industry only employs one-in-ten Illinois workers today. As manufacturing has declined, so too has the state’s labor movement: Illinois’ union coverage rate has fallen by 0.3 percentage points per year since 1983. The decade with the lowest property wealth inequality and lowest income inequality in Illinois was generally the 1960s. In these years, the Top 1 Percent of homes were 2.2 times as valuable as the median home and the Top 1 Percent of workers earned at least 3.4 times as much as the median worker. -

Agreements and Disclosures

AGREEMENTS AND DISCLOSURES 1604 Cherry Street, Vicksburg, MS 39180 Ph: 877-457-3654 Fax: 601-634-1707 Lost or Stolen Debit or Credit Cards: 800-682-6075 THESE AGREEMENTS AND DISCLOSURES CONTAIN IMPORTANT MEMBERSHIP INFORMATION, NECESSARY TRUTH-IN-SAVINGS ACCOUNT DISCLOSURES,L ELECTRONIC SERVICES AGREEMENT AND DISCLOSURES, FUNDS AVAILABILITY POLICY, WIRE TRANSFER AGREEMENT, AND PRIVACY POLICY DISCLOSURE. PLEASE BE CERTAIN TO READ THESE AGREEMENTS AND DISCLOSURES CAREFULLY AND NOTIFY US AT ONCE IF ANY PARTS ARE UNCLEAR. Throughout these Agreements and Disclosures, the references to "We," "Us," "Our" and "Credit Union" mean MUTUAL CREDIT UNION. The words "You" and "Your" mean each person applying for and/or using any of the services described herein. "Account" means any account or accounts established for You as set forth in these Agreements and Disclosures. The word "Card" means any ATM Card or VISA Debit Card issued to You by Us and any duplicates or renewals We may issue Our Audio Response System is hereinafter referred to as "Mobile Telephone System," whereas Our Personal Computer Account Access System is hereinafter referred to as "Online Banking," and Our Mobile Internet Account Access System is hereinafter referred to as "Mobile Banking." "E-Check" means any check which You authorize the payee to process electronically. For joint accounts, read singular pronouns in the plural. MUTUAL CREDIT UNION MEMBERSHIP To apply for membership with Mutual Credit Union You must complete, sign and such persons. By signing Your application for membership, You acknowledge return an application for membership. receipt of these Agreements and Disclosures, including the terms and conditions which apply to Your Accounts. -

ECON 8764-001 History of Economic Development

History of Economic Development Economics 8764-001 Fall 2012 Tuesday & Thursday 12:30-1:45 pm, Econ 5. Professor Carol H. Shiue, email [email protected], Econ 206B, Tue & Thur 2-3 p.m. Course Outline Overview This course examines competing explanations for cross-country differences in long run economic growth, addressing the question, “why are some countries so rich and other so poor” from a historical and comparative standpoint. The core issues that we examine cover the Middle Ages to the 20th century and focus attention on Britain and Northwestern Europe because that is where economic growth first occurred. Knowledge of standard analytical tools and empirical techniques of macro and micro is strongly recommended. This course has several objectives: the first is to show how theoretical approaches and quantitative tools can be applied to historical evidence. The second objective is to introduce students to research and paper writing in economic history and other applied fields of economics. We will be reading and discussing articles to learn how a research article is put together. You will also have many opportunities in this class to pose your own questions and present your ideas. This is a skill that is of immense value as you start to enter into the dissertation-writing phase of your program and will be spending more of your time doing research in economics. With practice, you will also feel more comfortable and confident in seminars, whether the seminar is your own or someone else’s. Course Requirements Classes will consist of lecture and student presentation and discussion.