Cranks, Caves and Campfires Ellis Stones’ Utopian Vision for a Suburban Landscape Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Australian Garden History Society Max Bourke Am

AUSTRALIAN GARDEN HISTORY SOCIETY NATIONAL ORAL HISTORY COLLECTION ACT MONARO RIVERINA BRANCH Interviewee: MAX BOURKE AM Interviewer: ROSLYN BURGE Date of interview: 20 NOVEMBER 2019 Place of Interview: CAMPBELL, ACT Details: TWO AUDIO FILES – TOTAL 2 HR 36 MIN Restrictions on use: NIL All quotations: SHOULD BE VERIFIED AGAINST THE ORIGINAL SPOKEN WORD IN THE INTERVIEW SELECT CHRONOLOGY / AGHS FOR A MORE DETAILED CHRONOLOGY- SEE RESUME ATTACHED 1941 Born - 18 December, Chatswood, NSW 1976-83 Australian Heritage Commission (founding CEO) 1981-87 ICOMOS (International Vice President 1984-87) 1990s Max joined AGHS - is a member of the ACT Monaro Riverina Branch 2000-2002 Branch Chair 2001-2007 National Management Committee 2005-2007 Vice-Chair (Chair, Colleen Morris) 2002 Announcement about Studies in Australian Garden History - Call for papers 2004 Editorial Advisory Committee 2004 AM Member of the Order of Australia: for service to heritage and arts organisations and to the development of government policy for the preservation of Australia’s historic and cultural environment 2007 Meandering about the Murray, national conference held in Albury, hosted by ACT Monaro Riverina Branch 2009 The English Garden, Yarralumla 2013 National Arboretum Canberra opened 2016 The Scientist in the Garden, national conference held in Canberra, hosted by ACT Monaro Riverina Branch When interviewed Chairman of Friends of Australian National Botanic Gardens SUMMARY Max Bourke spoke briefly about his childhood responses to his family’s interests in gardens and growing orchids and vegetables, and his own Canberra garden and the impact on gardens of climate change. His was first aware of the Society before it was formed, when working at the Australian Heritage Commission (AHC - of which Max was Foundation Director) and he, David Yencken and Reg Walker in 1976 first discussed how the Commission could strengthen not-for-profit organisations, including those involved in industrial archaeology and public history. -

Survey-Of-Post-War-Built-Heritage-In-Victoria-Stage-1-Heritage-Alliance-2008 Part2.Pdf (PDF File

Identifier House Other name Milston House (former) 027-086 Address 6 Reeves Court Group 027 Residential Building (Private) KEW Category 472 House LGA City of Boroondara Date/s 1955-56 Designer/s Ernest Milston NO IMAGE AVAILABLE Theme 6.0 Building Towns, Cities & the Garden State Sub-theme 6.7 Making Homes for Victorians Keywords Architect’s Own Significance Architectural; aesthetic References This butterfly-roofed modernist house was designed by Ernest P Goad, Melbourne Architecture, p 171 Milton, noted Czech-born émigré architect, for his own use. Existing Listings AHC National Trust Local HO schedule Local Heritage Study Identifier House Other name 027-087 Address 54 Maraboor Street Group 027 Residential Building (Private) LAKE BOGA Category 472 House LGA Rural City of Swan Hill Date/s c.1955? Designer/s Theme 6.0 Building Towns, Cities & the Garden State Sub-theme 6.7 Making Homes for Victorians Keywords Image: Simon Reeves, 2002 Significance Aesthetic References Probably a rare survivor of the 1950s fad for decorating John Belot, Our Glorious Home (1978) houses, gardens and fences with shells and ceramic shards. This “Domestic Featurism” was documented by John Belot in the 1970s, but few examples would now remain intact. The famous “shell houses” of Arthur Pickford at Ballarat and Albert Robertson at Phillip Island are both no longer extant. Existing Listings AHC National Trust Local HO schedule Local Heritage Study heritage ALLIANCE 146 Job 2008-07 Survey of Post-War Built Heritage in Victoria Identifier House Other name Reeve House (former) 027-088 Address 21a Green Gully Road Group 027 Residential Building (Private) KEILOR Category 472 House LGA City of Brimbank Date/s 1955-60 Designer/s Fritz Janeba NO IMAGE AVAILABLE Theme 6.0 Building Towns, Cities & the Garden State Sub-theme 6.7 Making Homes for Victorians Keywords Significance Architectural; References One of few known post-war commissions of this Austrian émigré, who was an influential teacher within Melbourne University’s School of Architecture. -

Mornington Peninsula Heritage Review Significant Place Citations

Attachment 4.2 Mornington Peninsula Heritage Review Area 1 – Mount Eliza, Mornington, Mount Martha Significant Place Citations December 2013 Mount Eliza Mornington Mount Martha Mornington Peninsula Shire Council With Context Pty Ltd, Heritage Intelligence Pty Ltd, Built Heritage Pty Ltd Attachment 4.2 20 Mornington Peninsula Shire, 2013 Mornington Peninsula Shire: Simon Lloyd – Heritage planner and project manager Rosalyn Franklin – for administrative supervision, mapping, policy development Lorraine Strong – obtaining information from building records Lorraine Huddle – Mornington Peninsula Shire Heritage Adviser Ana Borovic – for assistance with mapping and heritage database Dylan Toomey – for survey work and photography Nicholas Robinson, Kayla Cartledge, Jane Conway, Liam Renaut for administrative support Helen Bishop for proofreading the Thematic History Phil Thomas for preparation of local policies. Context Pty Ltd Project Team: Louise Honman Director David Helms Senior Consultant Natica Schmeder Senior Consultant Annabel Neylon Senior Consultant Ian Travers Senior Consultant Jessie Briggs Consultant. Built Heritage Pty Ltd - Project team: Simon Reeves, Director. Heritage Intelligence Pty Ltd - Project Team: Lorraine Huddle, Director. Additional research by Graeme Butler and Associates: Graeme Butler, Director. Attachment 4.2 Individual Places 35-37 Barkly Street, Mornington ...................................................................................................................... 7 28 Bath Street Mornington -

Victorian Historical Journal

VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF VICTORIA The Royal Historical Society of Victoria is a community organisation comprising people from many fields committed to collecting, researching and sharing an understanding of the history of Victoria. TheVictorian Historical Journal is a refereed journal publishing original and previously unpublished scholarly articles on Victorian history, or on Australian history where it illuminates Victorian history. It is published twice yearly by the Publications Committee, Royal Historical Society of Victoria. EDITORS Richard Broome, Emeritus Professor, La Trobe University, and Judith Smart, Honorary Associate Professor, RMIT University PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE Jill Barnard Rozzi Bazzani Sharon Betridge (Co-editor, History News) Marilyn Bowler Richard Broome (Convenor) (Co-Editor, History News) Marie Clark Jonathan Craig (Reviews Editor) John Rickard John Schauble Judith Smart (Co-editor, History News) Lee Sulkowska Carole Woods BECOME A MEMBER Membership of the Royal Historical Society of Victoria is open. All those with an interest in history are welcome to join. Subscriptions can be purchased at: Royal Historical Society of Victoria 239 A’Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia Telephone: 03 9326 9288 Email: [email protected] www.historyvictoria.org.au Journals are also available for purchase online: www.historyvictoria.org.au/publications/victorian-historical-journal VICTORIAN HISTORICAL JOURNAL ISSUE 291 VOLUME 90, NUMBER 1 JUNE 2019 Royal Historical Society of Victoria Victorian Historical Journal Published by the Royal Historical Society of Victoria 239 A’Beckett Street Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia Telephone: 03 9326 9288 Fax: 03 9326 9477 Email: [email protected] www.historyvictoria.org.au Copyright © the authors and the Royal Historical Society of Victoria 2018 All material appearing in this publication is copyright and cannot be reproduced without the written permission of the publisher and the relevant author. -

BALWYN and BALWYN NORTH HERITAGE STUDY (INCORPORATING DEEPDENE & GREYTHORN) Prepared for CITY of BOROONDARA

CITY OF BOROONDARA BALWYN AND BALWYN NORTH HERITAGE STUDY (INCORPORATING DEEPDENE & GREYTHORN) prepared for CITY OF BOROONDARA FINAL DRAFT REPORT: A ! "# $%&' P O B o ( 2 2 2 E ) e r a l d + 7 - 2 . / 0 u 1 l # 2 e r 1 # a ! e / 3 o ) / a p 2 o 4 e 5 % & - 5 + & & Schedule of Changes Issued Draft Report with outline citations November 28, 2012 Report with full citations and updated methodology February 19, 2013 Updated with minor revisions following meeting March 8, 2013 Updated with minor revisions, reformatting of Section D, one May 10, 2013 additional individual citation and new Appendix 2 Updated with minor revisions, one additional individual citation June 14, 2013 and new schedules to precinct citations Updated with minor revisions and corrections that were identified August 13, 2015 during the Public Exhibition period TABLE OF CONTENTS Section A Executive Summary 5 Section B Historical Overview 7 Section C Project Background, Brief and Methodology 13 Section D Recommendations 21 Section E Citations for Individual Heritage Places 35 Section F Citations for Heritage Precincts 141 Section G Select Bibliography 171 Appendix1 Remaining Outline Citations 173 Appendix 2 Original Master-list of Places 219 Appendix 3 Additional Places 233 B A L W Y N & B A L W Y N N O R T H H E R I T A G E S T U D Y : A U G U S T $ % & ' 3 4 B A L W Y N & B A L W Y N N O R T H H E R I T A G E S T U D Y : A U G U S T $ % & ' A: EXECUTIVE SUMMARY A.1 Balwyn and Balwyn North Heritage Study This report was commissioned by the City of Boroondara to provide a more rigorous heritage assessment of the suburbs of Balwyn and Balwyn North (including the localities of Deepdene and Greythorn), which were considered to be under- represented in the municipality's heritage overlay schedule. -

Vulnerable Scenery: Shifting Dynamics of the Natural Aesthetic in Australian Postwar Gardens

Vulnerable scenery: shifting dynamics of the natural aesthetic in Australian postwar gardens Christina Dyson PhD candidate, The University of Melbourne Co-editor, Australian Garden History Heritage consultant, Context Pty Ltd (Un)loved Modern Wednesday, 8 July 2009 Vulnerable scenery: shifting dynamics of the natural aesthetic in Australian postwar gardens • background • confounding loved/unloved qualities • conservation challenges • concluding thoughts: issues of professional practice Pamphlet distributed to new land Fülling, the Gordon and Gwen Pettit+Sevitt Lowline B3136 owners in the Eltham area, Ford garden, Eltham, Victoria, (www.pettitandsevitt.com.au) Eltham Tree Preservation from 1948 [2008] Society (Peter Glass papers, State Library of Victoria, Manuscripts Collection, PA 99/87, no date [c.1960s]) natural aesthetic: …gardens comprising predominantly Australian plants and intended to simulate the effects of ‘natural’ bushland - itself an imaginative and cultural construct. bush garden, and other descriptors • Australian garden (The Australasian, 1909; Mackennal, H.G. 1917) • native plant movement (Freeland, J.M. 1968) • artless naturalism (Goad, Philip 2002) • artful and imaginative landscape interpretations (Bull, Catherin 2002) • idealised bush (Ford, Gordon 1999) • native landscaping (Ramsay, Juliet 1991) • a native garden aesthetic (Cerwonka, Allaine 2004) • the natural garden (Latreille, Anne 1990) • the ‘natural’ style of gardening (Cuffley, Peter 1993) • the natural Australian garden (Ford, Gordon 1999) • Australian Native -

Annett E W Arner

Summary Background to the research Overlapping values: Art, activism, environmentalism, Reading the garden as text space, to screen built form, but also as a meditative structure that focus’ the mind artistic response, which over time through the development of a ‘language’ of The wall of this salon, brings into proximity, the beach, the bush, the topography and highlights the importance of the juxtaposition of mass and void as an ‘occult’ or more in tune with the spirit of a post WWII Australia, just a little further up the Oils, brushes and canvas, the tools of artist Peter Glass (1917-1997) are Caitlin’s reflection prompted a query into the Portraying these alternate perspectives of landscape, particularly in Sue Ford’s The archive of the late Gordon Ford, would not exist without the In this exhibition, Annette Warner presents her current research into the iconic This curatorial methodology broadens the discussion on how visual and historical I began this research in Gordon’s garden, some five-and-a-half years ago. I had not inward toward the garden and to the immediate experience. The bridging of the design, inspired by landscape and art practice. This period would ‘set the scene’ textures, colours and memories of landscape and gardens, sometimes associated intuitive practice. One of the main principles in the natural approach to design. Yarra. sometimes exchanged for the graphite pencil and trace in the studio of influence of the Tonalists on Gordon’s work. In-camera: behind the natural Australian garden contact sheets, meant the inclusion of half-finished work or work-in-progress, wilderness and the landscape garden Just to the right of the door was a small room lined with books. -

A Tale of Two Motels: the Times, the Architecture and the Architects*

David Yencken A Tale of Two Motels: the times, the architecture and the architects* MY INTRODUCTION TO ARCHITECTURE and building was humble and accidental. I learnt about design and building from the good fortune of working with outstanding Australian designers and from the necessity of learning some building skills to bring into being the projects with which I was engaged. The first project was a motel in Bairnsdale. It was the great adventure of my life. From it every later initiative and role evolved. As I travelled across Canada in my early twenties on my way to Australia, working my way to support myself, I was introduced to several wonders of the new world: hamburgers, three-minute carwashes and motels. None of these now ubiquitous American cultural exports was in common currency at that time in England or Australia. I landed in Sydney on 8 November 1954. A trip around Australia with a Canadian friend who had been at Cambridge with me and who turned up in Melbourne not long after my arrival introduced me to the delights of Australian country pubs – hammock beds and eggs for breakfast swimming in animal fat. It was during this trip that the idea of building a motel took shape, first as a joint venture with my friend and then, when he sensibly returned to Canada, on my own. The omens for such a venture were not propitious. There were no motels in Australia, at least to my knowledge or that of anyone I knew. I did not have nearly enough money and nothing else to fall back on. -

Connecting People with Plants Annual Report 2005–06 Royal Botanic Gardens Board Victoria

Connecting people with plants Annual Report 2005–06 Royal Botanic Gardens Board Victoria Contents Executive summary – Information Privacy Act 2002 Part six – Financial statements 71 and Health Records Act 2001 18 Auditor-General’s report 72 Complete Annual Report 2005–06 – Building and maintenance provisions of the Building RBG Declaration 74 Part one – Introduction 1 Act 1993 19 Operating Statement for the – Our Vision 2 – Whistleblowers Protection Act Reporting Period ended – Our Mission 2 2001, statement and procedures 19 30 June 2006 75 – Our Values 2 Financial overview 20 Balance Sheet as at – Our Charter 2 Comparison of financial results 21 30 June 2006 76 – Definitions 2 Consultancies 22 Statement of Recognised – Chairman’s foreword 3 Income and Expense for the Part three – Our employees 23 Reporting Period ended Part two – Our organisation 5 30 June 2006 77 Employee profile 24 Cashflow Statement for the Corporate governance 6 Employee support Reporting Period ended – Board committees 6 and development 26 30 June 2006 78 – Remuneration 6 Employee relations 27 – Board members 7 Notes to the financial statements Employee recognition 28 – Board attendance figures 7 for the year ended 30 June 2006 79 The organisation 8 Part four – Our achievements 29 Disclosure index 104 – RBG Cranbourne 8 Goal one 31 – RBG Melbourne 8 Goal two 41 Appendices 106 – National Herbarium of Victoria 8 Goal three 49 Appendix One – – ARCUE 9 Whistleblowers Protection – Visitor numbers 9 Part five – Our supporters 57 Act 2001 106 Royal Botanic Gardens’ Generous financial support 58 organisation chart 10 Royal Botanic Gardens Corporate Management Group 11 Foundation Victoria 59 Environmental performance 12 Director’s Circle 60 Legislation 15 Friends of the Royal Botanic Statements of compliance Gardens Cranbourne Inc. -

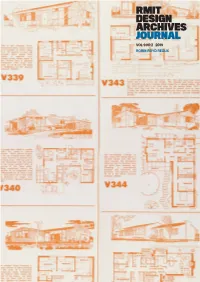

Rmit Design Archives Journal Vol 9 Nº 2 | 2019 Robin Boyd Redux Robin Boyd Redux

RMIT DESIGN ARCHIVES JOURNAL | VOL 9 Nº 2 | | VOL JOURNAL RMIT DESIGN ARCHIVES 9 Nº 2 RMIT DESIGN ARCHIVES JOURNAL VOL 9 Nº 2 | 2019 ROBIN BOYD REDUX ROBIN BOYD REDUX BOYD ROBIN RDA_Journal_21_9.2_Cover.indd 1 27/11/19 4:58 pm Contributors Dr Karen Burns is an architectural historian and theorist in the Melbourne School of Design at the University of Melbourne. Harriet Edquist is professor in the School of Architecture and Urban Design at RMIT University and Director of RMIT Design Archives. Dr Rory Hyde is the curator of contemporary architecture and urbanism at the Victoria & Albert Museum, adjunct senior research fellow at the University of Melbourne, and design advocate for the Mayor of London. John Macarthur is professor at the University of Queensland in the School of Architecture where his research focuses on the intellectual history of architecture, the aesthetics of architecture and its relation to the visual arts. Philip Goad is Chair of Architecture and Redmond Barry Distinguished Professor at the University of Melbourne. He is currently Gough Whitlam Malcolm Fraser Chair of Australian Studies at Harvard University for the 2019-2020 academic year. Virginia Mannering is a Melbourne-based designer, researcher and tutor in architectural design and history Dr Christine Phillips is an architect, researcher and academic within the architecture program in the School of Architecture and Urban Design at RMIT University. Dr Peter Raisbeck is an architect, researcher and academic at the Melbourne School of Design at the University of -

Taylor) Determination 2020 (No 3

Australian Capital Territory Public Place Names (Taylor) Determination 2020 (No 3) Disallowable instrument DI2020–54 made under the Public Place Names Act 1989, s 3 (Minister to determine names) 1 Name of instrument This instrument is the Public Place Names (Taylor) Determination 2020 (No 3). 2 Commencement This instrument commences on the day after its notification day. 3 Determination of Place Names I determine the place names as indicated in the schedule. Ben Ponton Delegate of the Minister for Planning and Land Management 22 April 2020 Authorised by the ACT Parliamentary Counsel—also accessible at www.legislation.act.gov.au SCHEDULE (See s 3) Division of Taylor – Architecture, town planning and urban design The location of the public places with the following names is indicated on the associated diagram. NAME ORIGIN SIGNIFICANCE Don Gazzard Donald Gazzard Architect, writer View (1929 – 2017) Training in the office of Harry Seidler in the early 1950s, Don Gazzard subsequently worked overseas, returning to Australia in 1960. Together with George Clarke, he established Clarke, Gazzard and Partners, an architectural, city planning and urban design firm. Following expansion, Clarke and Gazzard founded Urban Systems Corporation (c.1970), incorporating the firm. Gazzard received the first Royal Australian Institute of Architects (RAIA) NSW Chapter Wilkinson Award for domestic architecture for the Herbert House, Hunters Hill (1961). Subsequent projects include designs for project houses for Carlingford’s Kingsdene Estate (1960- 62), Wentworth Memorial Church, Vaucluse (1965) and the Sydney TAA Terminal (c.1974). His book ‘Australian Outrage: the decay of a visual environment’ (1966) originated from the 1964 exhibition he mounted for the RAIA by the same title. -

Manningham Heritage Study Review 2005 Volume 2: Heritage Place & Precinct Citations

Manningham Heritage Study Review 2005 Volume 2: Heritage Place & Precinct Citations Final 16 February, 2006 Prepared for Manningham City Council © Context Pty Ltd 2005 Project Team: David Helms, Senior Consultant Jackie Donkin, Consultant Karen Olsen, Senior Consultant Natica Schmeder, Consultant Martin Turnor, Consultant Dr Carlotta Kellaway, Historian Fiona Gruber, Historian Context Pty Ltd 22 Merri Street, Brunswick 3056 Phone 03 9380 6933 Facsimile 03 9380 4066 Email [email protected] i ii CONTENTS INTRODUCTION I Overview i Purpose i HOW TO USE II Introduction ii Description ii History iii Statement of Significance iii Recommendations iii REFERENCES IV LIST OF CITATIONS V CITATIONS VI iii MANNINGHAM HERITAGE STUDY REVIEW 2005 INTRODUCTION Overview This Heritage Place & Precinct Citations report comprises Volume 2 of the Manningham Heritage Study Review 2005 (the Study). The purpose of the Study is to complete the identification, assessment and documentation of places of post-contact cultural significance within Manningham City (the study area) and to make recommendations for their future conservation. This volume contains all the citations for heritage places and precincts throughout the City of Manningham including: • All of the places assessed or reviewed by this Study (see below). • All of the places identified or assessed by previous studies including the City of Doncaster & Templestowe Heritage Study (1991), City of Doncaster & Templestowe. Additional Sites Recommendations (1993), Doncaster & Templestowe Heritage Study Additional Historical Research (1994), and the Wonga Park Heritage Study (1996). • Places identified by individuals and organisations including Council’s Heritage Adviser, local historical societies and residents. The citations are derived from an electronic database known as the Manningham Local Heritage Places Database (Manningham LHPD), which uses a program that was developed by Heritage Victoria.