In the George Eastman Museum

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

0 0 0 0 Acasa Program Final For

PROGRAM ABSTRACTS FOR THE 15TH TRIENNIAL SYMPOSIUM ON AFRICAN ART Africa and Its Diasporas in the Market Place: Cultural Resources and the Global Economy The core theme of the 2011 ACASA symposium, proposed by Pamela Allara, examines the current status of Africa’s cultural resources and the influence—for good or ill—of market forces both inside and outside the continent. As nation states decline in influence and power, and corporations, private patrons and foundations increasingly determine the kinds of cultural production that will be supported, how is African art being reinterpreted and by whom? Are artists and scholars able to successfully articulate their own intellectual and cultural values in this climate? Is there anything we can do to address the situation? WEDNESDAY, MARCH 23, 2O11, MUSEUM PROGRAM All Museum Program panels are in the Lenart Auditorium, Fowler Museum at UCLA Welcoming Remarks (8:30). Jean Borgatti, Steven Nelson, and Marla C. Berns PANEL I (8:45–10:45) Contemporary Art Sans Frontières. Chairs: Barbara Thompson, Stanford University, and Gemma Rodrigues, Fowler Museum at UCLA Contemporary African art is a phenomenon that transcends and complicates traditional curatorial categories and disciplinary boundaries. These overlaps have at times excluded contemporary African art from exhibitions and collections and, at other times, transformed its research and display into a contested terrain. At a moment when many museums with so‐called ethnographic collections are expanding their chronological reach by teasing out connections between traditional and contemporary artistic production, many museums of Euro‐American contemporary art are extending their geographic reach by globalizing their curatorial vision. -

The Wild Boar from San Rossore

209.qxp 01-12-2009 12:04 Side 55 UDSTILLINGSHISTORIER OG UDSTILLINGSETIK ● NORDISK MUSEOLOGI 2009 ● 2, S. 55-79 Speaking to the Eye: The wild boar from San Rossore LIV EMMA THORSEN* Abstract: The article discusses a taxidermy work of a wild boar fighting two dogs. The tableau was made in 1824 by the Italian scientist Paolo Savi, director of the Natural History Museum in Pisa from 1823-1840. The point of departure is the sense of awe this brilliantly produced tableau evokes in the spectator. If an object could talk, what does the wild boar communicate? Stuffed animals are objects that operate in natural history exhibitions as well in several other contexts. They resist a standard classification, belonging to neither nature nor culture. The wild boar in question illustrates this ambiguity. To decode the tale of the boar, it is establis- hed as a centre in a network that connects Savi’s scientific and personal knowled- ge, the wild boar as a noble trophy, the development of the wild boar hunt in Tus- cany, perceptions of the boar and the connection between science and art. Key words: Natural history museum, taxidermy, wild boar, wild boar hunt, the wild boar in art, ornithology, natural history in Tuscany, Museo di Storia Naturale e del Territorio, Paolo Savi. In 1821, a giant male wild boar was killed at There is a complex history to this wild boar. San Rossore, the hunting property of the We have to understand the important role this Grand Duke of Toscana. It was killed during a species played in Italian and European hun- hunt arranged in honour of prominent guests ting tradition, the link between natural histo- of Ferdinand III. -

In the Museum with Roosevelt Michael Ross Canfield Enjoys a Chronicle of the Statesman’S Natural-History Legacy

COMMENT BOOKS & ARTS ZOOLOGY In the museum with Roosevelt Michael Ross Canfield enjoys a chronicle of the statesman’s natural-history legacy. he head of a Cape buffalo presents killed animals. This contradiction has exer- itself just inside the door of Theodore cised many. Teasing apart aspects of ethics, Roosevelt’s historical home, Sagamore morality, manliness and environmentalism THill, on Long Island, New York. A few steps in Roosevelt’s approach to collecting, Lunde further in are mounted rhinoceros horns, reveals how the president’s impulses over- then a trophy room framed by elephant tusks. lapped. He hunted for meat and sport — a This is, in effect, the personal natural-history common pursuit among the wealthy on both museum of the explorer, soldier and 26th US sides of the Atlantic — as well as science. president. Roosevelt also donated hundreds of That scientific strand was strong. Lunde specimens to the American Museum of Natu- describes how Roosevelt was able to “hold LIBRARY/ALAMY PICTURE EVANS MARY ral History in New York and the Smithsonian specimens in his hand”, whether bear, cou- Institution in Washington DC. Between these gar or bird, to hone his observational acuity. two kinds of museum — the private and the Roosevelt even chastised hunters who did not public — we find the Roosevelt of The Natu- learn in this way and report results appropri- ralist by Darrin Lunde, manager of the Smith- ately, because information could easily be lost sonian’s mammal collections. to science. Other areas of his life, particularly Lunde’s narrative stretches from Roosevelt’s his approach to politics and policymaking, youth to his return from a scientific safari show the imprint of these habits of observing, in what is now Kenya in 1909–10, a decade collecting disparate elements and informa- before his death. -

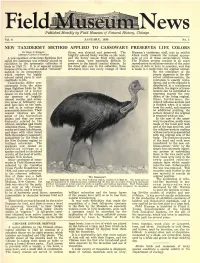

New Taxidermy Method Applied to Cassowary Preserves Life Colors

News Pvblished Monthly by Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago Vol. 6 JANUARY, 1935 No. 1 NEW TAXIDERMY METHOD APPLIED TO CASSOWARY PRESERVES LIFE COLORS By Karl P. Schmidt River, was skinned and preserved. The Museum's taxidermy staff, into an exhibit Assistant Curator of Reptiles brightly colored fleshy wattles on the neck, which really presents the natural appear- A new specimen of the large flightless bird and the horny casque filled with spongy ance of one of these extraordinary birds. called the cassowary was recently placed on bony tissue, were especially difficult to The Walters process consists in an exact exhibition in the systematic collection of preserve in the humid tropical climate. In reproduction in cellulose-acetate of the outer birds in Hall 21. It is of especial interest the dried skin now in the collection, these layers of skin or horn in question, and this because of the use of the so-called "celluloid" structures have lost every vestige of their is made in a mold from the original animal. method in its preparation By the admixture of the which renders its highly proper pigments in the dis- colored naked parts in veri- solved cellulose-acetate, the similitude to life. coloration is exactly repro- Cassowaries differ con- duced, and as the pigment is spicuously from the other distributed in a translucent large flightless birds by the medium, the degree of trans- development of a horny lucence can be controlled to casque on the head, and by represent exactly the con- the presence of brightly dition of the living original. -

Hear UR Season Two Episode 207 De-Extinction by Tom Fleischman

Hear UR Season Two Episode 207 De-Extinction By Tom Fleischman and Steve Roessner TOM Hear you are... MOTOR OF A BUS, ACCELERATING. VIBRATIONS SHAKING SEATS. SQUEAKS. TIRES AND WATER.MOTOR OF A BUS, ACCELERATING. VIBRATIONS SHAKING SEATS. SQUEAKS. TIRES AND WATER. TOM ...on a bus, heading south-east out of Rochester, New York. It’s a rainy Sunday morning in February, and there’s a major winter storm rolling in. BUS AUDIO OUT WEATHER FORECAST AUDIO IN/OUT BUS AUDIO RESUMES But you, and your fellow travelers--the production team for this season of Hear UR--are determined to complete the trip before the weather turns severe. Your destination, a small village in Wyoming County, where the 19th-century United States still resides. EXTERIOR SOUNDS OF THE TOWN. BIRDS. RUNNING WATER. AND THE SOUND OF FEET SHUFFLING INTO THE GREAT ROOM. TOM When you arrive, you step off the bus into another world. For one thing, it’s sunny and warm here, no hint of a blizzard at all. But then, you see the magnificent red brick building, that looks like a cross between a church, an armory, and a regal estate. Out front, a sign reads “Village Hall.” You step inside, into another time, and there in front of you, waiting, is Bill Neal. BACKGROUND AUDIO: BILL NEAL GIVING A TOUR ALMOST INAUDIBLY BILL NEAL So this is Lydia Avery Coonley Ward. And thanks to Lydia, we have the building, museum... TOM In the magnificent hall, you hear Bill talk about the creation of the building. How it was the gift of Lydia Avery Coonley Ward, who once summered in the town, and wanted to leave its residents with a gift. -

Domesticating Wilderness: How Nature and Culture Converge in the Museum Space

DOMESTICATING WILDERNESS: HOW NATURE AND CULTURE CONVERGE IN THE MUSEUM SPACE Thesis Submitted in Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts LISA GOULET Program in Museum Studies Graduate School of Arts and Science New York University April 2018 Abstract My thesis compares the Hall of North American Mammals at the American Museum of Natural History and High Line park. I argue that museums and other cultural institutions using museological methodologies seek to construct specific visual rhetorics and narratives in order to shape how visitors define, understand, and place themselves in relation to nature. Both spaces use a combination of artistic display techniques informed by a foundation of scientific knowledge to represent the results of major shifts in thought about how we define nature and respond to problematic human impacts from the eras prior to their construction. The Hall of North American Mammals uses diorama displays that most prominently feature iconic species of animals and majestic landscape paintings, following in a traditional style and appreciation for nature that emerged from specific artistic and scientific developments through the nineteenth century. Conversely, the High Line uses architecture and sculptural planting design to guide visitors along a predetermined series of vignettes that display not only the park itself but also contemporary art and the surrounding New York landscape, following an environmentally-minded ethic that emerged with the twentieth century environmental movement. Though both sites promote an aesthetic appreciation of nature that has origins in the visual culture established in the nineteenth century, the High Line attempts to contemporize this experience through the synthesis of nature and human activity while the Hall of North American Mammals rests more firmly in a dated experience of nature as an other, separated from the human realm. -

Scientific Taxidermy, US Natural History Museums

“Strict Fidelity to Nature”: Scientific Taxidermy, U.S. Natural History Museums, and Craft Consensus, 1880s-1930s Jonathan David Grunert Dissertation submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Science and Technology Studies Mark V. Barrow, Jr., Chair Matthew R. Goodrum Matthew Wisnioski Eileen Crist Patzig September 27, 2019 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: taxidermy, natural history, museum, scientific representation, visual culture “Strict Fidelity to Nature”: Scientific Taxidermy, U.S. Natural History Museums, and Craft Consensus, 1880s-1930s Jonathan David Grunert ABSTRACT As taxidermy increased in prominence in American natural history museums in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the idea of trying to replicate nature through mounts and displays became increasingly central. Crude practices of overstuffing skins gave way to a focus on the artistic modelling of animal skins over a sculpted plaster and papier-mâché form to create scientifically accurate and aesthetically pleasing mounts, a technique largely developed at Ward’s Natural Science Establishment in Rochester, New York. Many of Ward’s taxidermists utilized their authority in taxidermy practices as they formally organized into the short-lived Society of American Taxidermists (1880-1883) before moving into positions in natural history museums across the United States. Through examinations of published and archival museum materials, as well as historic mounts, I argue that taxidermists at these museums reached an unspoken consensus concerning how their mounts would balance pleasing aesthetics with scientific accuracy, while adjusting their practices as they considered the priorities of numerous stakeholders. -

Constructed Reality: the Diorama As

CONSTRUCTED REALITY: THE DIORAMA AS ART Diane Fox explores the encounter - the returned animal gaze that holds the viewer in communication. But is communication effectively achieved through the naturalistic artifice of natural history dioramas? Text by Diane Fox Diane Fox Wrapped, Milwaukee Public Museum 13 he term diorama, derived from the Greek “dia” Medici’s collection of natural curiosities, fossils, plants and (through) and “orama,” (to see), was first coined animals. T by the French scenic painter, physicist, and There were a few exceptions to this type of inventor of the daguerreotype L.J.M. Daguerre and his display that may be considered forerunners of Akeley’s co-worker Charles-Marie Bouton in 1821. (1) It referred total habitat dioramas. British taxidermist, Walter Potter, to large sheets of transparent fabric painted with realistic was creating scenes of anthropomorphized animals images on both sides that were designed to be viewed engaged in human activity for his Bramber Museum in from a distance through a framing device that hide the 1880. Entertaining “Dime Museums” featured living paintings’ vanishing points. When Daguerre’s first people posed in front of painted scenery. (3) Charles diorama opened in Paris in July 1822 there were two Wilson Peale, an artist and early pioneer in taxidermy paintings, one by Daguerre and the other by Bouton. and museum display, created America’s first natural One showed an interior and the other a landscape. history museum in 1786 in Philadelphia. His displays were When sunlight was redirected with mirrors and shone unusual, as he tried to “accurately re-create living creatures through the cloth it produced changing effects with his art and painted skies and landscapes on the backs of transforming day into night, winter into summer, thus the cases displaying his taxidermy specimens.” (2) The heightening its illusion of reality. -

Civilisations, 41 | 1993 Contribution À L'histoire Jusque 1934 De La Création De L'institut Des Parcs

Civilisations Revue internationale d'anthropologie et de sciences humaines 41 | 1993 Mélanges Pierre Salmon II Contribution à l'histoire jusque 1934 de la création de l'institut des parcs nationaux du Congo belge Jean-Paul Harroy Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/civilisations/1732 DOI : 10.4000/civilisations.1732 ISSN : 2032-0442 Éditeur Institut de sociologie de l'Université Libre de Bruxelles Édition imprimée Date de publication : 1 septembre 1993 Pagination : 427-442 ISBN : 2-87263-094-5 ISSN : 0009-8140 Référence électronique Jean-Paul Harroy, « Contribution à l'histoire jusque 1934 de la création de l'institut des parcs nationaux du Congo belge », Civilisations [En ligne], 41 | 1993, mis en ligne le 30 juillet 2009, consulté le 30 avril 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/civilisations/1732 ; DOI : 10.4000/ civilisations.1732 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 30 avril 2019. © Tous droits réservés Contribution à l'histoire jusque 1934 de la création de l'institut des parcs ... 1 Contribution à l'histoire jusque 1934 de la création de l'institut des parcs nationaux du Congo belge Jean-Paul Harroy Preambule 1 Le présent article m'a été souvent demandé par des personnes inquiètes de ce qu'aucune synthèse importante ait jamais décrit les étapes, amorçées vers 1920, qui ont conduit le 26 novembre 1934 à la création de l'Institut des Parcs nationaux du Congo Belge (I.P.N.C.B.). Et je me juge un peu responsable de cette lacune, étant devenu aujourd'hui probablement le seul survivant des derniers témoins de la fin de cette époque. -

Carl Akeley, Mary Bradley, and the American Search for the Missing Link

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Faculty Publications, Department of History History, Department of 9-1-2006 "Gorilla Trails in Paradise": Carl Akeley, Mary Bradley, and the American Search for the Missing Link Jeannette Eileen Jones University of Nebraska - Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historyfacpub Part of the History Commons Jones, Jeannette Eileen, ""Gorilla Trails in Paradise": Carl Akeley, Mary Bradley, and the American Search for the Missing Link" (2006). Faculty Publications, Department of History. 28. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/historyfacpub/28 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the History, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications, Department of History by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in The Journal of American Culture 29:3 (September 2006), pp. 321–336. doi:10.1111/j.1542-734X.2006.00374.x Copyright © 2006 Jeannette Eileen Jones; published by Blackwell Publishing, Inc. “Gorilla Trails in Paradise”: Carl Akeley, Mary Bradley, and the American Search for the Missing Link Jeannette Eileen Jones University of Nebraska–Lincoln n 1881, Ward’s Natural Science Bulletin published “[s]uspicionless of guile” strayed beneath the I the anonymously authored poem “The Miss- trees where the simian court convened. When ing Link.” Referencing decades-long debates over the “monarch spake his love” to her, “the lady the relationship of man to ape, and the spiritual, smiled on him,” at which point the gorilla king intellectual, and moral capacities of apes, chim- stuck “his great prehensile toes” in her hair and panzees, and orangutans (Desmond 45, 141, 289), carried her off into his arboreal kingdom. -

Akeley Inside the Elephant: Trajectory of a Taxidermic Image

POP 7 (1+2) pp. 43–61 Intellect Limited 2016 Philosophy of Photography Volume 7 Numbers 1 & 2 © 2016 Intellect Ltd Article. English language. doi: 10.1386/pop.7.1-2.43_1 BERND BEHR Camberwell College of Arts Akeley inside the elephant: Trajectory of a taxidermic image Keywords Abstract sprayed concrete As a process distinct from its poured cousin, sprayed concrete involves using compressed air to propel cement taxidermy with various chemical admixtures at a surface. Used in tunnelling for rock surface stabilization, and above Carl Akeley ground for securing slopes and fabricating fake rockeries, its chimeric character ranges from the polished cinematography landscapes of skateparks and swimming pools to mimicking cast concrete in structural repair work. The Paul Strand origins of this industrial process lie with taxidermist Carl E. Akeley (1864–1926), who invented it during his James Tiptree Jr pioneering work in the proto-photographic field of natural habitat dioramas at the Chicago Field Museum in realism 1907. Further cementing André Bazin’s notion of photography as embalmment, Akeley also invented a robotics unique 35mm cine camera during his time at the American Museum of Natural History, New York. The essay explores this historical intersection between photography, taxidermy and architecture, and its wider implications for thinking through photography’s material contingency. 43 POP_7.1&2_Behr_43-61.indd 43 1/20/17 3:03 PM Bernd Behr Buried deep under the southern tip of the Appenzell Alps in Switzerland, in the labyrinthine network of a vast testing facility for the mining and tunnelling industries, the construction division of the chemical multinational BASF leads an annual workshop on the very latest in robotic applications of sprayed concrete. -

Chapter 1: Vertebrates

http://www.natsca.org Care and Conservation of Natural History Collections Title: Vertebrates Author(s): Hendry, D. Source: Hendry, D. (1999). Vertebrates. In: Carter, D. & Walker, A. (eds). (1999). Chapter 1: Care and Conservation of Natural History Collections. Oxford: Butterwoth Heinemann, pp. 1 - 36. URL: http://www.natsca.org/care-and-conservation The pages that follow are reproduced with permission from publishers, editors and all contributors from Carter, D. & Walker, A. K. (1999). Care and Conservation of Natural History Collections. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann. While this text was accurate at the time of publishing (1999), current advice may differ. NatSCA are looking to provide more current guidance and offer these pages as reference materials to be considered alongside other sources. The following pages are the result of optical character recognition and may contain misinterpreted characters. If you do find errors, please email [email protected] citing the title of the document and page number; we will do our best to correct them. NatSCA supports open access publication as part of its mission is to promote and support natural science collections. NatSCA uses the Creative Commons Attribution License (CCAL) http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/ for all works we publish. Under CCAL authors retain ownership of the copyright for their article, but authors allow anyone to download, reuse, reprint, modify, distribute, and/or copy articles in NatSCA publications, so long as the original authors and source are cited. Plate 3 A traditional mannikin bound with wood wool. This technique was used to mount most large mammals in the UK prior to 1980 (Dick Hendry).