Computing Invariants of Hyperbolic Coxeter Groups

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

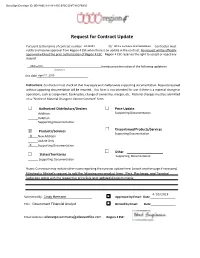

Request for Contract Update

DocuSign Envelope ID: 0E48A6C9-4184-4355-B75C-D9F791DFB905 Request for Contract Update Pursuant to the terms of contract number________________R142201 for _________________________ Office Furniture and Installation Contractor must notify and receive approval from Region 4 ESC when there is an update in the contract. No request will be officially approved without the prior authorization of Region 4 ESC. Region 4 ESC reserves the right to accept or reject any request. Allsteel Inc. hereby provides notice of the following update on (Contractor) this date April 17, 2019 . Instructions: Contractor must check all that may apply and shall provide supporting documentation. Requests received without supporting documentation will be returned. This form is not intended for use if there is a material change in operations, such as assignment, bankruptcy, change of ownership, merger, etc. Material changes must be submitted on a “Notice of Material Change to Vendor Contract” form. Authorized Distributors/Dealers Price Update Addition Supporting Documentation Deletion Supporting Documentation Discontinued Products/Services X Products/Services Supporting Documentation X New Addition Update Only X Supporting Documentation Other States/Territories Supporting Documentation Supporting Documentation Notes: Contractor may include other notes regarding the contract update here: (attach another page if necessary). Attached is Allsteel's request to add the following new product lines: Park, Recharge, and Townhall Collection along with the respective price -

![The Geometry of Nim Arxiv:1109.6712V1 [Math.CO] 30](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8642/the-geometry-of-nim-arxiv-1109-6712v1-math-co-30-48642.webp)

The Geometry of Nim Arxiv:1109.6712V1 [Math.CO] 30

The Geometry of Nim Kevin Gibbons Abstract We relate the Sierpinski triangle and the game of Nim. We begin by defining both a new high-dimensional analog of the Sierpinski triangle and a natural geometric interpretation of the losing positions in Nim, and then, in a new result, show that these are equivalent in each finite dimension. 0 Introduction The Sierpinski triangle (fig. 1) is one of the most recognizable figures in mathematics, and with good reason. It appears in everything from Pascal's Triangle to Conway's Game of Life. In fact, it has already been seen to be connected with the game of Nim, albeit in a very different manner than the one presented here [3]. A number of analogs have been discovered, such as the Menger sponge (fig. 2) and a three-dimensional version called a tetrix. We present, in the first section, a generalization in higher dimensions differing from the more typical simplex generalization. Rather, we define a discrete Sierpinski demihypercube, which in three dimensions coincides with the simplex generalization. In the second section, we briefly review Nim and the theory behind optimal play. As in all impartial games (games in which the possible moves depend only on the state of the game, and not on which of the two players is moving), all possible positions can be divided into two classes - those in which the next player to move can force a win, called N-positions, and those in which regardless of what the next player does the other player can force a win, called P -positions. -

Notes Has Not Been Formally Reviewed by the Lecturer

6.896 Topics in Algorithmic Game Theory February 22, 2010 Lecture 6 Lecturer: Constantinos Daskalakis Scribe: Jason Biddle, Debmalya Panigrahi NOTE: The content of these notes has not been formally reviewed by the lecturer. It is recommended that they are read critically. In our last lecture, we proved Nash's Theorem using Broweur's Fixed Point Theorem. We also showed Brouwer's Theorem via Sperner's Lemma in 2-d using a limiting argument to go from the discrete combinatorial problem to the topological one. In this lecture, we present a multidimensional generalization of the proof from last time. Our proof differs from those typically found in the literature. In particular, we will insist that each step of the proof be constructive. Using constructive arguments, we shall be able to pin down the complexity-theoretic nature of the proof and make the steps algorithmic in subsequent lectures. In the first part of our lecture, we present a framework for the multidimensional generalization of Sperner's Lemma. A Canonical Triangulation of the Hypercube • A Legal Coloring Rule • In the second part, we formally state Sperner's Lemma in n dimensions and prove it using the following constructive steps: Colored Envelope Construction • Definition of the Walk • Identification of the Starting Simplex • Direction of the Walk • 1 Framework Recall that in the 2-dimensional case we had a square which was divided into triangles. We had also defined a legal coloring scheme for the triangle vertices lying on the boundary of the square. Now let us extend those concepts to higher dimensions. 1.1 Canonical Triangulation of the Hypercube We begin by introducing the n-simplex as the n-dimensional analog of the triangle in 2 dimensions as shown in Figure 1. -

Interval Vector Polytopes

Interval Vector Polytopes By Gabriel Dorfsman-Hopkins SENIOR HONORS THESIS ROSA C. ORELLANA, ADVISOR DEPARTMENT OF MATHEMATICS DARTMOUTH COLLEGE JUNE, 2013 Contents Abstract iv 1 Introduction 1 2 Preliminaries 4 2.1 Convex Polytopes . 4 2.2 Lattice Polytopes . 8 2.2.1 Ehrhart Theory . 10 2.3 Faces, Face Lattices and the Dual . 12 2.3.1 Faces of a Polytope . 12 2.3.2 The Face Lattice of a Polytope . 15 2.3.3 Duality . 18 2.4 Basic Graph Theory . 22 3IntervalVectorPolytopes 23 3.1 The Complete Interval Vector Polytope . 25 3.2 TheFixedIntervalVectorPolytope . 30 3.2.1 FlowDimensionGraphs . 31 4TheIntervalPyramid 38 ii 4.1 f-vector of the Interval Pyramid . 40 4.2 Volume of the Interval Pyramid . 45 4.3 Duality of the Interval Pyramid . 50 5 Open Questions 57 5.1 Generalized Interval Pyramid . 58 Bibliography 60 iii Abstract An interval vector is a 0, 1 -vector where all the ones appear consecutively. An { } interval vector polytope is the convex hull of a set of interval vectors in Rn.Westudy several classes of interval vector polytopes which exhibit interesting combinatorial- geometric properties. In particular, we study a class whose volumes are equal to the catalan numbers, another class whose legs always form a lattice basis for their affine space, and a third whose face numbers are given by the pascal 3-triangle. iv Chapter 1 Introduction An interval vector is a 0, 1 -vector in Rn such that the ones (if any) occur consecu- { } tively. These vectors can nicely and discretely model scheduling problems where they represent the length of an uninterrupted activity, and so understanding the combi- natorics of these vectors is useful in optimizing scheduling problems of continuous activities of certain lengths. -

COXETER GROUPS (Unfinished and Comments Are Welcome)

COXETER GROUPS (Unfinished and comments are welcome) Gert Heckman Radboud University Nijmegen [email protected] October 10, 2018 1 2 Contents Preface 4 1 Regular Polytopes 7 1.1 ConvexSets............................ 7 1.2 Examples of Regular Polytopes . 12 1.3 Classification of Regular Polytopes . 16 2 Finite Reflection Groups 21 2.1 NormalizedRootSystems . 21 2.2 The Dihedral Normalized Root System . 24 2.3 TheBasisofSimpleRoots. 25 2.4 The Classification of Elliptic Coxeter Diagrams . 27 2.5 TheCoxeterElement. 35 2.6 A Dihedral Subgroup of W ................... 39 2.7 IntegralRootSystems . 42 2.8 The Poincar´eDodecahedral Space . 46 3 Invariant Theory for Reflection Groups 53 3.1 Polynomial Invariant Theory . 53 3.2 TheChevalleyTheorem . 56 3.3 Exponential Invariant Theory . 60 4 Coxeter Groups 65 4.1 Generators and Relations . 65 4.2 TheTitsTheorem ........................ 69 4.3 The Dual Geometric Representation . 74 4.4 The Classification of Some Coxeter Diagrams . 77 4.5 AffineReflectionGroups. 86 4.6 Crystallography. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. 92 5 Hyperbolic Reflection Groups 97 5.1 HyperbolicSpace......................... 97 5.2 Hyperbolic Coxeter Groups . 100 5.3 Examples of Hyperbolic Coxeter Diagrams . 108 5.4 Hyperbolic reflection groups . 114 5.5 Lorentzian Lattices . 116 3 6 The Leech Lattice 125 6.1 ModularForms ..........................125 6.2 ATheoremofVenkov . 129 6.3 The Classification of Niemeier Lattices . 132 6.4 The Existence of the Leech Lattice . 133 6.5 ATheoremofConway . 135 6.6 TheCoveringRadiusofΛ . 137 6.7 Uniqueness of the Leech Lattice . 140 4 Preface Finite reflection groups are a central subject in mathematics with a long and rich history. The group of symmetries of a regular m-gon in the plane, that is the convex hull in the complex plane of the mth roots of unity, is the dihedral group of order 2m, which is the simplest example of a reflection Dm group. -

Binary Icosahedral Group and 600-Cell

Article Binary Icosahedral Group and 600-Cell Jihyun Choi and Jae-Hyouk Lee * Department of Mathematics, Ewha Womans University 52, Ewhayeodae-gil, Seodaemun-gu, Seoul 03760, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-2-3277-3346 Received: 10 July 2018; Accepted: 26 July 2018; Published: 7 August 2018 Abstract: In this article, we have an explicit description of the binary isosahedral group as a 600-cell. We introduce a method to construct binary polyhedral groups as a subset of quaternions H via spin map of SO(3). In addition, we show that the binary icosahedral group in H is the set of vertices of a 600-cell by applying the Coxeter–Dynkin diagram of H4. Keywords: binary polyhedral group; icosahedron; dodecahedron; 600-cell MSC: 52B10, 52B11, 52B15 1. Introduction The classification of finite subgroups in SLn(C) derives attention from various research areas in mathematics. Especially when n = 2, it is related to McKay correspondence and ADE singularity theory [1]. The list of finite subgroups of SL2(C) consists of cyclic groups (Zn), binary dihedral groups corresponded to the symmetry group of regular 2n-gons, and binary polyhedral groups related to regular polyhedra. These are related to the classification of regular polyhedrons known as Platonic solids. There are five platonic solids (tetrahedron, cubic, octahedron, dodecahedron, icosahedron), but, as a regular polyhedron and its dual polyhedron are associated with the same symmetry groups, there are only three binary polyhedral groups(binary tetrahedral group 2T, binary octahedral group 2O, binary icosahedral group 2I) related to regular polyhedrons. -

Sequential Evolutionary Operations of Trigonometric Simplex Designs For

SEQUENTIAL EVOLUTIONARY OPERATIONS OF TRIGONOMETRIC SIMPLEX DESIGNS FOR HIGH-DIMENSIONAL UNCONSTRAINED OPTIMIZATION APPLICATIONS Hassan Musafer Under the Supervision of Dr. Ausif Mahmood DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIRMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOHPY IN COMPUTER SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING THE SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING UNIVERSITY OF BRIDGEPORT CONNECTICUT May, 2020 SEQUENTIAL EVOLUTIONARY OPERATIONS OF TRIGONOMETRIC SIMPLEX DESIGNS FOR HIGH-DIMENSIONAL UNCONSTRAINED OPTIMIZATION APPLICATIONS c Copyright by Hassan Musafer 2020 iii SEQUENTIAL EVOLUTIONARY OPERATIONS OF TRIGONOMETRIC SIMPLEX DESIGNS FOR HIGH-DIMENSIONAL UNCONSTRAINED OPTIMIZATION APPLICATIONS ABSTRACT This dissertation proposes a novel mathematical model for the Amoeba or the Nelder- Mead simplex optimization (NM) algorithm. The proposed Hassan NM (HNM) algorithm allows components of the reflected vertex to adapt to different operations, by breaking down the complex structure of the simplex into multiple triangular simplexes that work sequentially to optimize the individual components of mathematical functions. When the next formed simplex is characterized by different operations, it gives the simplex similar reflections to that of the NM algorithm, but with rotation through an angle determined by the collection of nonisometric features. As a consequence, the generating sequence of triangular simplexes is guaranteed that not only they have different shapes, but also they have different directions, to search the complex landscape of mathematical problems and to perform better performance than the traditional hyperplanes simplex. To test reliability, efficiency, and robustness, the proposed algorithm is examined on three areas of large- scale optimization categories: systems of nonlinear equations, nonlinear least squares, and unconstrained minimization. The experimental results confirmed that the new algorithm delivered better performance than the traditional NM algorithm, represented by a famous Matlab function, known as "fminsearch". -

The Hippo Pathway Component Wwc2 Is a Key Regulator of Embryonic Development and Angiogenesis in Mice Anke Hermann1,Guangmingwu2, Pavel I

Hermann et al. Cell Death and Disease (2021) 12:117 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41419-021-03409-0 Cell Death & Disease ARTICLE Open Access The Hippo pathway component Wwc2 is a key regulator of embryonic development and angiogenesis in mice Anke Hermann1,GuangmingWu2, Pavel I. Nedvetsky1,ViktoriaC.Brücher3, Charlotte Egbring3, Jakob Bonse1, Verena Höffken1, Dirk Oliver Wennmann1, Matthias Marks4,MichaelP.Krahn 1,HansSchöler5,PeterHeiduschka3, Hermann Pavenstädt1 and Joachim Kremerskothen1 Abstract The WW-and-C2-domain-containing (WWC) protein family is involved in the regulation of cell differentiation, cell proliferation, and organ growth control. As upstream components of the Hippo signaling pathway, WWC proteins activate the Large tumor suppressor (LATS) kinase that in turn phosphorylates Yes-associated protein (YAP) and its paralog Transcriptional coactivator-with-PDZ-binding motif (TAZ) preventing their nuclear import and transcriptional activity. Inhibition of WWC expression leads to downregulation of the Hippo pathway, increased expression of YAP/ TAZ target genes and enhanced organ growth. In mice, a ubiquitous Wwc1 knockout (KO) induces a mild neurological phenotype with no impact on embryogenesis or organ growth. In contrast, we could show here that ubiquitous deletion of Wwc2 in mice leads to early embryonic lethality. Wwc2 KO embryos display growth retardation, a disturbed placenta development, impaired vascularization, and finally embryonic death. A whole-transcriptome analysis of embryos lacking Wwc2 revealed a massive deregulation of gene expression with impact on cell fate determination, 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; 1234567890():,; cell metabolism, and angiogenesis. Consequently, a perinatal, endothelial-specific Wwc2 KO in mice led to disturbed vessel formation and vascular hypersprouting in the retina. -

Petrie Schemes

Canad. J. Math. Vol. 57 (4), 2005 pp. 844–870 Petrie Schemes Gordon Williams Abstract. Petrie polygons, especially as they arise in the study of regular polytopes and Coxeter groups, have been studied by geometers and group theorists since the early part of the twentieth century. An open question is the determination of which polyhedra possess Petrie polygons that are simple closed curves. The current work explores combinatorial structures in abstract polytopes, called Petrie schemes, that generalize the notion of a Petrie polygon. It is established that all of the regular convex polytopes and honeycombs in Euclidean spaces, as well as all of the Grunbaum–Dress¨ polyhedra, pos- sess Petrie schemes that are not self-intersecting and thus have Petrie polygons that are simple closed curves. Partial results are obtained for several other classes of less symmetric polytopes. 1 Introduction Historically, polyhedra have been conceived of either as closed surfaces (usually topo- logical spheres) made up of planar polygons joined edge to edge or as solids enclosed by such a surface. In recent times, mathematicians have considered polyhedra to be convex polytopes, simplicial spheres, or combinatorial structures such as abstract polytopes or incidence complexes. A Petrie polygon of a polyhedron is a sequence of edges of the polyhedron where any two consecutive elements of the sequence have a vertex and face in common, but no three consecutive edges share a commonface. For the regular polyhedra, the Petrie polygons form the equatorial skew polygons. Petrie polygons may be defined analogously for polytopes as well. Petrie polygons have been very useful in the study of polyhedra and polytopes, especially regular polytopes. -

Arxiv:1705.01294V1

Branes and Polytopes Luca Romano email address: [email protected] ABSTRACT We investigate the hierarchies of half-supersymmetric branes in maximal supergravity theories. By studying the action of the Weyl group of the U-duality group of maximal supergravities we discover a set of universal algebraic rules describing the number of independent 1/2-BPS p-branes, rank by rank, in any dimension. We show that these relations describe the symmetries of certain families of uniform polytopes. This induces a correspondence between half-supersymmetric branes and vertices of opportune uniform polytopes. We show that half-supersymmetric 0-, 1- and 2-branes are in correspondence with the vertices of the k21, 2k1 and 1k2 families of uniform polytopes, respectively, while 3-branes correspond to the vertices of the rectified version of the 2k1 family. For 4-branes and higher rank solutions we find a general behavior. The interpretation of half- supersymmetric solutions as vertices of uniform polytopes reveals some intriguing aspects. One of the most relevant is a triality relation between 0-, 1- and 2-branes. arXiv:1705.01294v1 [hep-th] 3 May 2017 Contents Introduction 2 1 Coxeter Group and Weyl Group 3 1.1 WeylGroup........................................ 6 2 Branes in E11 7 3 Algebraic Structures Behind Half-Supersymmetric Branes 12 4 Branes ad Polytopes 15 Conclusions 27 A Polytopes 30 B Petrie Polygons 30 1 Introduction Since their discovery branes gained a prominent role in the analysis of M-theories and du- alities [1]. One of the most important class of branes consists in Dirichlet branes, or D-branes. D-branes appear in string theory as boundary terms for open strings with mixed Dirichlet-Neumann boundary conditions and, due to their tension, scaling with a negative power of the string cou- pling constant, they are non-perturbative objects [2]. -

Regular Polyhedra Through Time

Fields Institute I. Hubard Polytopes, Maps and their Symmetries September 2011 Regular polyhedra through time The greeks were the first to study the symmetries of polyhedra. Euclid, in his Elements showed that there are only five regular solids (that can be seen in Figure 1). In this context, a polyhe- dron is regular if all its polygons are regular and equal, and you can find the same number of them at each vertex. Figure 1: Platonic Solids. It is until 1619 that Kepler finds other two regular polyhedra: the great dodecahedron and the great icosahedron (on Figure 2. To do so, he allows \false" vertices and intersection of the (convex) faces of the polyhedra at points that are not vertices of the polyhedron, just as the I. Hubard Polytopes, Maps and their Symmetries Page 1 Figure 2: Kepler polyhedra. 1619. pentagram allows intersection of edges at points that are not vertices of the polygon. In this way, the vertex-figure of these two polyhedra are pentagrams (see Figure 3). Figure 3: A regular convex pentagon and a pentagram, also regular! In 1809 Poinsot re-discover Kepler's polyhedra, and discovers its duals: the small stellated dodecahedron and the great stellated dodecahedron (that are shown in Figure 4). The faces of such duals are pentagrams, and are organized on a \convex" way around each vertex. Figure 4: The other two Kepler-Poinsot polyhedra. 1809. A couple of years later Cauchy showed that these are the only four regular \star" polyhedra. We note that the convex hull of the great dodecahedron, great icosahedron and small stellated dodecahedron is the icosahedron, while the convex hull of the great stellated dodecahedron is the dodecahedron. -

Platonic Solids Generate Their Four-Dimensional Analogues

This is a repository copy of Platonic solids generate their four-dimensional analogues. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/85590/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Dechant, Pierre-Philippe orcid.org/0000-0002-4694-4010 (2013) Platonic solids generate their four-dimensional analogues. Acta Crystallographica Section A : Foundations of Crystallography. pp. 592-602. ISSN 1600-5724 https://doi.org/10.1107/S0108767313021442 Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 1 Platonic solids generate their four-dimensional analogues PIERRE-PHILIPPE DECHANT a,b,c* aInstitute for Particle Physics Phenomenology, Ogden Centre for Fundamental Physics, Department of Physics, University of Durham, South Road, Durham, DH1 3LE, United Kingdom, bPhysics Department, Arizona State University, Tempe, AZ 85287-1604, United States, and cMathematics Department, University of York, Heslington, York, YO10 5GG, United Kingdom. E-mail: [email protected] Polytopes; Platonic Solids; 4-dimensional geometry; Clifford algebras; Spinors; Coxeter groups; Root systems; Quaternions; Representations; Symmetries; Trinities; McKay correspondence Abstract In this paper, we show how regular convex 4-polytopes – the analogues of the Platonic solids in four dimensions – can be constructed from three-dimensional considerations concerning the Platonic solids alone.