Nbaa Business Aviation Fact Book

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weather and Aviation: How Does Weather Affect the Safety and Operations of Airports and Aviation, and How Does FAA Work to Manage Weather-Related Effects?

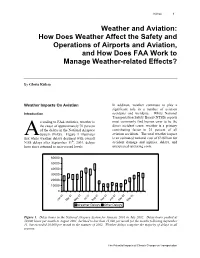

Kulesa 1 Weather and Aviation: How Does Weather Affect the Safety and Operations of Airports and Aviation, and How Does FAA Work to Manage Weather-related Effects? By Gloria Kulesa Weather Impacts On Aviation In addition, weather continues to play a significant role in a number of aviation Introduction accidents and incidents. While National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) reports ccording to FAA statistics, weather is most commonly find human error to be the the cause of approximately 70 percent direct accident cause, weather is a primary of the delays in the National Airspace contributing factor in 23 percent of all System (NAS). Figure 1 illustrates aviation accidents. The total weather impact that while weather delays declined with overall is an estimated national cost of $3 billion for NAS delays after September 11th, 2001, delays accident damage and injuries, delays, and have since returned to near-record levels. unexpected operating costs. 60000 50000 40000 30000 20000 10000 0 1 01 01 0 01 02 02 ul an 01 J ep an 02 J Mar May S Nov 01 J Mar May Weather Delays Other Delays Figure 1. Delay hours in the National Airspace System for January 2001 to July 2002. Delay hours peaked at 50,000 hours per month in August 2001, declined to less than 15,000 per month for the months following September 11, but exceeded 30,000 per month in the summer of 2002. Weather delays comprise the majority of delays in all seasons. The Potential Impacts of Climate Change on Transportation 2 Weather and Aviation: How Does Weather Affect the Safety and Operations of Airports and Aviation, and How Does FAA Work to Manage Weather-related Effects? Thunderstorms and Other Convective In-Flight Icing. -

Business & Commercial Aviation

BUSINESS & COMMERCIAL AVIATION LEONARDO AW609 PERFORMANCE PLATEAUS OCEANIC APRIL 2020 $10.00 AviationWeek.com/BCA Business & Commercial Aviation AIRCRAFT UPDATE Leonardo AW609 Bringing tiltrotor technology to civil aviation FUEL PLANNING ALSO IN THIS ISSUE Part 91 Department Inspections Is It Airworthy? Oceanic Fuel Planning Who Says It’s Ready? APRIL 2020 VOL. 116 NO. 4 Performance Plateaus Digital Edition Copyright Notice The content contained in this digital edition (“Digital Material”), as well as its selection and arrangement, is owned by Informa. and its affiliated companies, licensors, and suppliers, and is protected by their respective copyright, trademark and other proprietary rights. Upon payment of the subscription price, if applicable, you are hereby authorized to view, download, copy, and print Digital Material solely for your own personal, non-commercial use, provided that by doing any of the foregoing, you acknowledge that (i) you do not and will not acquire any ownership rights of any kind in the Digital Material or any portion thereof, (ii) you must preserve all copyright and other proprietary notices included in any downloaded Digital Material, and (iii) you must comply in all respects with the use restrictions set forth below and in the Informa Privacy Policy and the Informa Terms of Use (the “Use Restrictions”), each of which is hereby incorporated by reference. Any use not in accordance with, and any failure to comply fully with, the Use Restrictions is expressly prohibited by law, and may result in severe civil and criminal penalties. Violators will be prosecuted to the maximum possible extent. You may not modify, publish, license, transmit (including by way of email, facsimile or other electronic means), transfer, sell, reproduce (including by copying or posting on any network computer), create derivative works from, display, store, or in any way exploit, broadcast, disseminate or distribute, in any format or media of any kind, any of the Digital Material, in whole or in part, without the express prior written consent of Informa. -

General Aviation Aircraft Propulsion: Power and Energy Requirements

UNCLASSIFIED General Aviation Aircraft Propulsion: Power and Energy Requirements • Tim Watkins • BEng MRAeS MSFTE • Instructor and Flight Test Engineer • QinetiQ – Empire Test Pilots’ School • Boscombe Down QINETIQ/EMEA/EO/CP191341 RAeS Light Aircraft Design Conference | 18 Nov 2019 | © QinetiQ UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED Contents • Benefits of electrifying GA aircraft propulsion • A review of the underlying physics • GA Aircraft power requirements • A brief look at electrifying different GA aircraft types • Relationship between battery specific energy and range • Conclusions 2 RAeS Light Aircraft Design Conference | 18 Nov 2019 | © QinetiQ UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED Benefits of electrifying GA aircraft propulsion • Environmental: – Greatly reduced aircraft emissions at the point of use – Reduced use of fossil fuels – Reduced noise • Cost: – Electric aircraft are forecast to be much cheaper to operate – Even with increased acquisition cost (due to batteries), whole-life cost will be reduced dramatically – Large reduction in light aircraft operating costs (e.g. for pilot training) – Potential to re-invigorate the GA sector • Opportunities: – Makes highly distributed propulsion possible – Makes hybrid propulsion possible – Key to new designs for emerging urban air mobility and eVTOL sectors 3 RAeS Light Aircraft Design Conference | 18 Nov 2019 | © QinetiQ UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED Energy conversion efficiency Brushless electric motor and controller: • Conversion efficiency ~ 95% for motor, ~ 90% for controller • Variable pitch propeller efficiency -

Business Opportunities in Aircraft Cabin Conversion and Refurbishing

Business Opportunities in Aircraft Cabin Conversion and Refurbishing Mihaela F. Niţă1 and Dieter Scholz2 Hamburg University of Applied Sciences, Berliner Tor 9, 20099 Hamburg, Germany This paper identifies several meaningful business opportunity cases in the area of aircraft cabin conversion and refurbishing and predicts the market volume and the world distribution for each of them: 1.) international cabins, 2.) domestic cabins, 3.) aircraft on operating lease, 4.) freighter conversions and 5.) VIP completions. This implies the determination of cabin modification/conversion scenarios, along with their duration and frequency. Factors driving the cabin conversion and refurbishing are identified. Several aircraft databases, containing the current world feet as well as the forecasted fleet for the next years, are analyzed. The results are obtained by creating a program able to read and analyze the gathered data. It is shown that about 38000 cabin redesigns will be undertaken within the next 20 years. About 2500 conversions from jetliners into freighters and 25000 cabin modifications at VIP standards will emerge on the market. The North American and European markets will keep providing good business opportunities in this area. The Asian market, however, is growing fast, and its very strong influence on demand puts it in the front rank for the next 20 years. Nomenclature agescenario_limit = aircraft age for which the refurbishing is no longer planned by the operator. dateaircraft_delivery = date of the aircraft first delivery datemodification -

Light Commercial and General Aviation Chair: Gerald S

A1J03: Committee on Light Commercial and General Aviation Chair: Gerald S. McDougall, Southeast Missouri State University Light Commercial and General Aviation Growth Opportunities Will Abound GERALD W. BERNSTEIN, Stanford Transportation Group DAVID S. LAWRENCE, Aviation Market Research The new millennium offers numerous opportunities for light commercial and general aviation. The extent to which this diverse industry can take advantage of these opportunities depends on our ability to: (1) maintain steady, albeit slow, economic growth; (2) undertake research and development of new and enhanced technologies that improve performance and lower costs, (3) forge alliances and approach aircraft production from a total system perspective; and (4) develop and maintain an air traffic system (facilities and control) that is able to efficiently accommodate the expected growth in demand for all categories of air travel. The greatest challenge for the industry is whether government policies and regulations continue to adhere to fiscal and monetary policies that promote economic growth worldwide and provide the necessary investments in our air traffic system to reduce congestion and avoid the distorting influences of user fees or artificial limits to access. HELICOPTER AVIATION Subcommittee A1J03 (1) The helicopter industry can be characterized as technologically mature but unstable in the structure of both its manufacturing and operating sectors. This anomaly is the result of worldwide reductions in military helicopter procurement after years of buildup as well as reduced tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union. In addition, and not unrelated to military cutbacks, the trend toward consolidation of military contractors has seriously affected the mostly subsidiary helicopter business. -

Aviation Annual Report

2018 Aviation Annual Report Aviation Aircraft Use Summary U.S. Forest Service 2018 Table of Contents Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................... 1 Table 1 – 2018 Forest Service Total Aircraft Available ..................................................................... 2 Introduction: The Forest Service Aviation Program...................................................................................... 3 Aviation Utilization and Cost Information .................................................................................................... 4 2018 At-A-Glance ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Aviation Use .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Table 2 and Figure 1 – Aircraft Total Use CY 2014-2018................................................................... 4 Figure 2 – CY 2018 Flight Hours by Month........................................................................................ 5 Table 3 and Figure 3 – Percent of CY 2018 Flight Time by Aircraft Type .......................................... 5 Table 4 – CY 2018 Aircraft Use by Region/Agency ............................................................................ 6 Aviation Cost ........................................................................................................................................ -

Intro to Aviation

NORTH DAKOTA AVIATION ASSOCIATION www.FLY-ND.com VOL. 32 • ISSUE 2 SPRING 2020 “When everything seems to be going against you, remember the plane takes off against the wind, not with it.” ~HENRY FORD IN THIS ISSUE intro to aviation NORTH DAKOTA AVIATION ASSOCIATION From the Editorial Committee www.www.FLFLY-NDY-ND.com.com The Editorial Board would like to welcome Nicolette Russell as the new editor of the FLY-ND Quarterly. With The official publication of the North Dakota Aviation Association training in marketing and work experience in aviation, we are confident our contributors, advertisers, and readers will enjoy FLY-ND Quarterly Editorial Committee Nicolette Russell, Editor ([email protected]) working with her. Congratulations and welcome, Nicolette! Elizabeth Bjerke, Chris Brown, Mike McHugh, Zach Peterson, Joshua Simmers If you have comments, advertising needs, individuals or businesses to add to the mailing list, or article ideas, please Send Address Changes To: [email protected] contact Nicolette at [email protected]. FLY-ND Quarterly, P.O. Box 5020, Bismarck, ND 58502-5020 Welcome to the spring issue of the FLY-ND Quarterly, The Quarterly is published four times a year (winter, spring, summer and fall). where tales of exciting changes and flying await you within Advertising Inquiries: [email protected] these pages. Perhaps it is because I am a pilot, I cannot help Advertising deadline is the 1st of the preceding month. but see an introduction to aviation as a theme for this issue. Whether it is regarding UAS operators, airport managers, or 2019-2020 BOARD MEMBERS BOARD 2019-2020 Larry Mueller – Board Member future army aviators, the simple things we do as an aviation Red River State Bank community encourage not just the future of our industry, NORTH DAKOTA Tanner Overland – Board Member AVIATION ASSOCIATION Overland Aviation but also introduce all the joy and fulfillment for those who Chad Symington – Board Member benefit from it. -

Efficient Light Aircraft Design – Options from Gliding

Efficient Light Aircraft Design – Options from Gliding Howard Torode Member of General Aviation Group and Chairman BGA Technical Committee Presentation Aims • Recognise the convergence of interest between ultra-lights and sailplanes • Draw on experiences of sailplane designers in pursuit of higher aerodynamic performance. • Review several feature of current sailplanes that might be of wider use. • Review the future for the recreational aeroplane. Lift occurs in localised areas A glider needs efficiency and manoeuvrability Drag contributions for a glider Drag at low speed dominated by Induced drag (due to lift) Drag at high ASW-27 speeds Glider (total) drag polar dominated by profile drag & skin friction So what are the configuration parameters? - Low profile drag: Wing section design is key - Low skin friction: maximise laminar areas - Low induced drag – higher efficiencies demand greater spans, span efficiency and Aspect Ratio - Low parasitic drag – reduce excrescences such as: undercarriage, discontinuities of line and no leaks/gaps. - Low trim drag – small tails with efficient surface coupled with low stability for frequent speed changing. - Wide load carrying capacity in terms of pilot weight and water ballast Progress in aerodynamic efficiency 1933 - 2010 1957: Phoenix (16m) 1971: Nimbus 2 (20.3m) 2003: Eta (30.8m) 2010: Concordia (28m) 1937: Wiehe (18m) Wooden gliders Metal gliders Composite gliders In praise of Aspect Ratio • Basic drag equation in in non-dimensional, coefficient terms: • For an aircraft of a given scale, aspect ratio is the single overall configuration parameter that has direct leverage on performance. Induced drag - the primary contribution to drag at low speed, is inversely proportional to aspect ratio • An efficient wing is a key driver in optimising favourable design trades in other aspects of performance such as wing loading and cruise performance. -

Design of a Light Business Jet Family David C

Design of a Light Business Jet Family David C. Alman Andrew R. M. Hoeft Terry H. Ma AIAA : 498858 AIAA : 494351 AIAA : 820228 Cameron B. McMillan Jagadeesh Movva Christopher L. Rolince AIAA : 486025 AIAA : 738175 AIAA : 808866 I. Acknowledgements We would like to thank Mr. Carl Johnson, Dr. Neil Weston, and the numerous Georgia Tech faculty and students who have assisted in our personal and aerospace education, and this project specifically. In addition, the authors would like to individually thank the following: David C. Alman: My entire family, but in particular LCDR Allen E. Alman, USNR (BSAE Purdue ’49) and father James D. Alman (BSAE Boston University ’87) for instilling in me a love for aircraft, and Karrin B. Alman for being a wonderful mother and reading to me as a child. I’d also like to thank my friends, including brother Mark T. Alman, who have provided advice, laughs, and made life more fun. Also, I am forever indebted to Roe and Penny Stamps and the Stamps President’s Scholarship Program for allowing me to attend Georgia Tech and to the Georgia Tech Research Institute for providing me with incredible opportunities to learn and grow as an engineer. Lastly, I’d like to thank the countless mentors who have believed in me, helped me learn, and Page i provided the advice that has helped form who I am today. Andrew R. M. Hoeft: As with every undertaking in my life, my involvement on this project would not have been possible without the tireless support of my family and friends. -

Preventive Maintenance

Maintenance Aspects of Owning Your Own Aircraft Introduction According to 14 CFR Part 43, Maintenance, Preventive Maintenance, Rebuilding, and Alteration, the holder of a pilot certificate issued under 14 CFR Part 61 may perform specified preventive maintenance on any aircraft owned or operated by that pilot, as long as the aircraft is not used under 14 CFR Part 121, 127, 129, or 135. This pamphlet provides information on authorized preventive maintenance. How To Begin Here are several important points to understand before you attempt to perform your own preventive maintenance: First, you need to understand that authorized preventive maintenance cannot involve complex assembly operations. Second, you should carefully review 14 CFR Part 43, Appendix A, Subpart C (Preventive Maintenance), which provides a list of the authorized preventive maintenance work that an owner pilot may perform. Third, you should conduct a self-analysis as to whether you have the ability to perform the work satisfactorily and safely. Fourth, if you do any of the preventive maintenance authorized in 14 CFR Part 43, you will need to make an entry in the appropriate logbook or record system in order to document the work done. The entry must include the following information: • A description of the work performed, or references to data that are acceptable to the Administrator. • The date of completion. • The signature, certificate number, and kind of certificate held by the person performing the work. Note that the signature constitutes approval for return to service only for work performed. Examples of Preventive Maintenance Items The following is a partial list of what a certificated pilot who meets the conditions in 14 CFR Part 43 can do: • Remove, install, and repair landing gear tires. -

2021 AHNA Options Catalogue

OPTIONS CATALOGUE 2021 Return to the Table of Contents Contact and Order Information U.S.A: +1 800-COPTER-1 [email protected] Canada: +1 800-267-4999 [email protected] © July 2021 Airbus Helicopters, all rights reserved. 002 | Options Catalogue 2021 Options Catalogue INTRODUCTION At Airbus Helicopters in North America, our engineering excellence and completions capability is an integral part of meeting your operating requirements. We are committed to providing OEM approved equipment modifications that further enhance your experience with our product line. This catalogue illustrates a grouping of our most important and interesting options available for the H125, H130, H135, and H145 aircraft families. Airbus Helicopters, Inc. is a certified “Design Approval Organization” by the Federal Aviation Administration. Airbus Helicopters Canada is a certified “Design Approval Organization” by Transport Canada. As customer centers, we have also been recognized as an Authorized Design Organization by the Airbus Helicopters Group (AH Group). For more information, please visit Airbus World or see contact information on the next page. Airbus Helicopters' Airbus World customer portal simplifies customers’ daily operations and allows them to focus on what really matters: their business. Air- bus World is an innovative online platform for accessing technical publications, placing orders and quotations, managing fleet data as well as warranty claims, and receiving quick responses to support and services questions. Airbus Helicopters reserves the right to make configuration and data changes at any time without notice. Information contained in this document is expressed in good faith and does not constitute any offer or contract with Airbus Helicopters. -

Aircraft Fleet Trends

Aircraft Fleet Trends The aircraft fleet based and utilized in Minnesota ranges from the smallest single-engine airplanes used by general aviation pilots to the largest wide-body aircraft used for long haul domestic and international commercial travel. Wide-body aircraft are large enough to accommodate two passenger aisles with seven to ten seats across the aircraft. National and global trends are affecting the way airlines, corporations, and private pilots purchase and utilize their aircraft. This paper provides insight into aircraft fleet trends. Every year the FAA evaluates how the economy impacts aviation by forecasting changes in the aircraft fleet, including all types of aircraft from large commercial service aircraft to single-seat general aviation airplanes and drones. The 20-year forecasts also evaluate how many hours pilots are flying, how many passengers are taking commercial flights, and the demand for cargo flights. The results are published annually in the FAA Aerospace Forecasts. General Aviation Fleet The total active general aviation fleet was in decline between 2008 and 2013.1 Beginning in 2014, deliveries of general aviation aircraft fleet began to gradually increase. In 2017, the FAA forecasts stated the active general aviation fleet would increase by an average annual rate of 0.1 percent over the 21-year forecast period. There are three categories of aircraft included in the general aviation fleet: piston powered aircraft, turbine powered aircraft, and light sport aircraft. Piston aircraft have piston powered engines connected to propellers on aircraft which allow the aircraft to move through the air and on the ground. Piston aircraft fly at lower altitudes than turbine powered aircraft.