The Late Pleistocene Sequence at Wells, Somerset

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 4 – Management Plan Review, Statement of Consultation

Appendix 4 – Management Plan Review, Statement of Consultation From: Cindy Carter [mailto:[email protected]] Sent: 17 April 2018 08:13 To: John Flannigan <[email protected]>; Julie Cooper <[email protected]>; Lane, Thomas (NE) <[email protected]>; Sarah Jackson <[email protected]>; [email protected];[email protected] Cc: Jim Hardcastle <[email protected]>; Sarah Catling <[email protected]> Subject: Mendip Hills AONB Management Plan 2019-2024 Review - Planning Workshop Dear all, As part of the review of the Mendip Hills AONB Management Plan, we are looking to hold a planning workshop on the draft Management Plan 2019-2024 and opportunities to consider how the objectives and policies within the Management Plan can be written to assist planning and other officers. The Mendip Hills AONB Management Plan once adopted is a material consideration in the planning process, both for plan-making and decision-taking. Attached, proposed agenda for the Planning Workshop to be held on Monday, 4th June 2018, 9:30 (start 10:00)-1:00 (lunch provided) at the Mendip Hills AONB Unit offices at Charterhouse in the Mendip Hills. Please could you forward on the invitation to relevant planning managers and it would be good to have at least 1-2 representatives (planning or landscaping officers) from the Local Planning Authorities and Natural England. It will also be a good opportunity for officers from the different LPAs/Natural England to liaise on the Mendip Hills AONB and cross-boundary considerations. Please could officer attendance be confirmed to the Mendip Hills AONB Unit by Friday, 25th May 2018 ([email protected] or Tel: 01761 462338) together with any dietary or other requirements. -

42 North Road, Wells, Somerset BA5 2TL £325,000

42 North Road, Wells, Somerset BA5 2TL £325,000 A detached, individual house with a south facing rear garden, garage and off road parking in popular North Road which is a short distance from the city centre. The property was built in the late 1980's and offers scope for further extension (stpp). No onward chain. The accommodation comprises entrance hall, sitting room, kitchen, ground floor cloakroom, integral garage (with scope to provide further accommodation), three bedrooms and a bathroom. Mainly double glazed windows. Gas fired central heating. Off road parking to the front. Level, south facing rear garden. Energy Efficiency Rating = D Telephone: 01749 671020 www.jeaneshollandburnell.co.uk 42 North Road, Wells, Somerset BA5 2TL LOCATION KITCHEN 9' 5'' x 7' 11'' (2.877m x 2.425m) Wells is the smallest city in England and offers a Double glazed window to the front. Fitted with a vibrant high street with a variety of independent shops range of limed oak-effect wall and base units. Single and restaurants as well as a twice weekly market and drainer stainless steel sink unit. Electric cooker point. a choice of supermarkets including Waitrose. At the Plumbing for automatic washing machine. Double very heart of the city is the medieval Cathedral, radiator. Bishop’s Palace and Vicars’ Close (reputed to be the oldest surviving residential street in Europe). Bristol and Bath lie c. 22 miles to the north and north- east respectively with mainline train stations to London at Castle Cary (c.11 miles) as well as Bristol and Bath. Bristol International Airport is c.15 miles to the north-west. -

An Example from Weston-Super-Mare

How Heritage can underpin Placemaking – an example from Weston-super-Mare (or......The Slow Drip Feed and The Wild Splashy Fountain....................) What’s that It’s a good idea to do both of these things then? Hello! This is who we are Our official name is the North Somerset Council Placemaking & Growth Development Team This is where Not exactly a snappy title is it – most people just know us as “the Weston team”, or the “ask Rachel/Chris/Cara/Samantha/Edward, we work - they will know” team! Rachel (Development and Regeneration Programme Manager) Chris (Principal Project Officer) Cara (Heritage Action Zone Project Officer) Samantha (Communications Officer) Edward (Programme Support Officer) Sadly, Samantha and Edward have had to stay in Weston to hold the fort – but the rest of us are here. Our Journey How did we get here? There was a lack of recognition that Weston had any architectural and historic merit – let alone what we could use it for. Overall ingrained perceptions – “Heritage is boring” “Heritage will stop us doing stuff” “Heritage is a waste of money – it doesn’t do anything” “No point – it’s only Weston. Not like its Bath or anything” It all started with an Urban Panel visit – we had to get other people to tell us Weston was architecturally and historically a great place! Tactics – five What worked for us key themes 1. Heritage, Arts & Culture are usually all mixed together and are hard to separate – so don’t try to 2. Bring your key stakeholders on board 3. Start to empower the local community 4. -

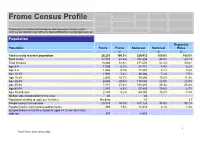

Frome Census Profile

Frome Census Profile Produced by the Partnership Intelligence Unit, Somerset County Council 2011 Census statistics from Office for National Statistics [email protected] Population England & Population Frome Frome Somerset Somerset Wales % % % Total usually resident population 26,203 100.0% 529,972 100.0% 100.0% Total males 12,739 48.6% 258,396 48.8% 49.2% Total females 13,464 51.4% 271,576 51.2% 50.8% Age 0-4 1,659 6.3% 28,717 5.4% 6.2% Age 5-9 1,543 5.9% 27,487 5.2% 5.6% Age 10-15 1,936 7.4% 38,386 7.2% 7.0% Age 16-24 2,805 10.7% 54,266 10.2% 11.9% Age 25-44 6,685 25.5% 119,246 22.5% 27.4% Age 45-64 7,171 27.4% 150,210 28.3% 25.4% Age 65-74 2,247 8.6% 57,463 10.8% 8.7% Age 75 and over 2,157 8.2% 54,197 10.2% 7.8% Median age of population in the area 40 44 Population density (people per hectare) No data 1.5 3.7 People living in households 25,814 98.5% 517,124 97.6% 98.2% People living in communal establishments 389 1.5% 12,848 2.4% 1.8% Schoolchildren or full-time students aged 4+ at non term-time address 307 8,053 1 Frome Facts: 2011 census data Identity England & Ethnic Group Frome Frome Somerset Somerset Wales % % % White Total 25,625 97.8% 519,255 98.0% 86.0% White: English/Welsh/Scottish/ Northern Irish/British 24,557 93.7% 501,558 94.6% 80.5% White: Irish 142 0.5% 2,257 0.4% 0.9% White: Gypsy or Irish Traveller 91 0.3% 733 0.1% 0.1% White: Other White 835 3.2% 14,707 2.8% 4.4% Black and Minority Ethnic Total 578 2.2% 10,717 2.0% 14.0% Mixed: White and Black Caribbean 57 0.2% 1,200 0.2% 0.8% Mixed: White and Black African 45 0.2% -

WESTON PLACEMAKING STRATEGY 03 Image by Paul Blakemore 3.0 Weston Placemaking Strategy 20 3.0 Weston Placemaking Strategy 21

Image by Paul Blakemore ON THE BEACH AT WESTON, WE SET OFF THROUGH WILD SWIMMERS WAIT IN LINE, THE OLD ESTATE, TO JOIN THE ROUGH BEYOND THE SCHOOL, AND TUMBLE TIDE TOWARDS THE GOLF COURSE, AND SURFACE FROM WHERE BEST MATES, THE RUSH OF LIFE. MIKE AND DAVE, ONCE PLAYED, HOW BRAVE THEY ARE — COLLECTING TRUANT FLY-AWAYS. ALL GOOSEBUMPS AND GRACE. WE REACH OUR BREATHLESS DESTINATION: UPHILL, OUT ON THE EDGE, WHERE THE SKY IS AN ARROW THEY FEEL A SENSE OF PLACE. THROUGH OUR HEART LOOK UP AT THE SOFTENED AND A PROBLEM SHARED JAWLINE OF THIS TOWN. IS A PROBLEM HALVED. FLAT HOLM, STEEP HOLM, THERE IT IS — THE CLEARING, BREAN DOWN. WITH ITS LAUGHTERFUL HERE, WE ARE LOST OF BLUEBELLS, AND INSTANTLY FOUND. AND THEN THE CHURCH, THE SKY, THE BIRDS. Contents Covid-19 This project had engaged with thousands of people about their town and their hopes for 02–03 the future by the time Covid-19 hit the UK. 1 Introduction People had expressed their ambitions for a more diversified town centre, with opportunities for leisure and play; space for business to start, invest and grow; and better homes with empty sites finally built out. 04–15 As in all parts of the country, the lockdown had 2 Weston-super-Mare a severe impact on the economy in the town centre and a visitor economy largely predicated on high volumes of day visitors. Prolonged and combined efforts and partnership between national, regional and local government, 16–27 employers, community networks and local 3 SuperWeston people will be needed to restore confidence and economic activity. -

Geology of the Shepton Mallet Area (Somerset)

Geology of the Shepton Mallet area (Somerset) Integrated Geological Surveys (South) Internal Report IR/03/94 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY INTERNAL REPORT IR/03/00 Geology of the Shepton Mallet area (Somerset) C R Bristow and D T Donovan Contributor H C Ivimey-Cook (Jurassic biostratigraphy) The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data are used with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Ordnance Survey licence number GD 272191/1999 Key words Somerset, Jurassic. Subject index Bibliographical reference BRISTOW, C R and DONOVAN, D T. 2003. Geology of the Shepton Mallet area (Somerset). British Geological Survey Internal Report, IR/03/00. 52pp. © NERC 2003 Keyworth, Nottingham British Geological Survey 2003 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of Survey publications is available from the BGS Keyworth, Nottingham NG12 5GG Sales Desks at Nottingham and Edinburgh; see contact details 0115-936 3241 Fax 0115-936 3488 below or shop online at www.thebgs.co.uk e-mail: [email protected] The London Information Office maintains a reference collection www.bgs.ac.uk of BGS publications including maps for consultation. Shop online at: www.thebgs.co.uk The Survey publishes an annual catalogue of its maps and other publications; this catalogue is available from any of the BGS Sales Murchison House, West Mains Road, Edinburgh EH9 3LA Desks. 0131-667 1000 Fax 0131-668 2683 The British Geological Survey carries out the geological survey of e-mail: [email protected] Great Britain and Northern Ireland (the latter as an agency service for the government of Northern Ireland), and of the London Information Office at the Natural History Museum surrounding continental shelf, as well as its basic research (Earth Galleries), Exhibition Road, South Kensington, London projects. -

Palaeolithic and Pleistocene Sites of the Mendip, Bath and Bristol Areas

Proc. Univ. Bristol Spelacol. Soc, 19SlJ, 18(3), 367-389 PALAEOLITHIC AND PLEISTOCENE SITES OF THE MENDIP, BATH AND BRISTOL AREAS RECENT BIBLIOGRAPHY by R. W. MANSFIELD and D. T. DONOVAN Lists of references lo works on the Palaeolithic and Pleistocene of the area were published in these Proceedings in 1954 (vol. 7, no. 1) and 1964 (vol. 10, no. 2). In 1977 (vol. 14, no. 3) these were reprinted, being then out of print, by Hawkins and Tratman who added a list ai' about sixty papers which had come out between 1964 and 1977. The present contribution is an attempt to bring the earlier lists up to date. The 1954 list was intended to include all work before that date, but was very incomplete, as evidenced by the number of older works cited in the later lists, including the present one. In particular, newspaper reports had not been previously included, but are useful for sites such as the Milton Hill (near Wells) bone Fissure, as are a number of references in serials such as the annual reports of the British Association and of the Wells Natural History and Archaeological Society, which are also now noted for the first time. The largest number of new references has been generated by Gough's Cave, Cheddar, which has produced important new material as well as new studies of finds from the older excavations. The original lists covered an area from what is now the northern limit of the County of Avon lo the southern slopes of the Mendips. Hawkins and Tratman extended that area to include the Quaternary Burtle Beds which lie in the Somerset Levels to the south of the Mendips, and these are also included in the present list. -

Knapp Farm Hillfarrance, Taunton, Somerset

Knapp Farm Hillfarrance, Taunton, Somerset Knapp Farm Exeter, approximately 29 miles away is the most thriving city in the South West and offers Hillfarrance, Taunton, a wide choice of cultural activities with the Somerset TA4 1AN theatre, the museum, arts centre and a wealth of good shopping, including John Lewis, A beautifully restored Grade II and restaurants. There is also a Waitrose supermarket both in Exeter and Wellington. Listed farmhouse with modern Exeter University is recognised as one of the and traditional outbuildings set best in the country. The M5 motorway provides links to the A38 to Plymouth or the A30 to in 18 acres Cornwall to the South and Bristol and London to the North and East. There are regular rail Wellington 4 miles, Taunton 4 miles, services to London Paddington from Taunton Exeter 29 miles and Exeter. Exeter and Bristol International Airports provides an ever increasing number of Entrance hall | Sitting room | Drawing room domestic and international flights including two Dining room | Kitchen/breakfast room | Boot flights a day to London City Airport. room | Downstairs cloakroom | Downstairs shower room | Master bedroom with stand- alone bath and ensuite shower room | Four further bedrooms, two with ensuites | Family bathroom Gardens | Paddocks | Barn | Granary barn Open fronted Dutch barn | Wood stores In all approximately 18 acres Location The pretty village of Hillfarrance provides a parish church and public house, whilst nearby Oake provides further amenities including shop/ post office and popular primary school, as well as the Oake Manor golf course. Taunton has excellent schools for boys and girls of all ages, including Taunton School, Kings College, Queen’s College and King’s Hall. -

Here Needs Conserving and Enhancing

OS EXPLORER MAP OS EXPLORER MAP OS EXPLORER MAP OS EXPLORER MAP 141 141 154 153 GRID REFERENCE GRID REFERENCE GRID REFERENCE GRID REFERENCE A WILD LAND VISITOR GUIDE VISITOR ST 476587 ST466539 ST578609 ST386557 POSTCODE POSTCODE POSTCODE POSTCODE READY FOR BS40 7AU CAR PARK AT THE BOTTOM OF BS27 3QF CAR PARK AT THE BOTTOM BS40 8TF PICNIC AND VISITOR FACILITIES, BS25 1DH KINGS WOOD CAR PARK BURRINGTON COMBE OF THE GORGE NORTH EAST SIDE OF LAKE ADVENTURE BLACK DOWN & BURRINGTON HAM CHEDDAR GORGE CHEW VALLEY LAKE CROOK PEAK Courtesy of Cheddar Gorge & Caves This area is a very special part of Mendip.Open The internationally famous gorge boasts the highest Slow down and relax around this reservoir that sits in The distinctive peak that most of us see from the heathland covers Black Down, with Beacon Batch at inland limestone cliffs in the country. Incredible cave the sheltered Chew Valley. Internationally important M5 as we drive by. This is iconic Mendip limestone its highest point. Most of Black Down is a Scheduled systems take you back through human history and are for the birds that use the lake and locally loved by the countryside, with gorgeous grasslands in the summer ADVENTURE Monument because of the archaeology from the late all part of the visitor experience. fishing community. and rugged outcrops of stone to play on when you get Stone Age to the Second World War. to the top. Travel on up the gorge and you’ll be faced with Over 4000 ducks of 12 different varieties stay on READY FOR FOR READY Burrington Combe and Ham are to the north and adventure at every angle. -

Notice of Election

NOTICE OF ELECTION Police and Crime Commissioner Election Avon and Somerset Police Area 1. An election is to be held for the Police and Crime Commissioner for the Avon and Somerset Police Area. 2. Nomination papers can be obtained from the office of the Police Area Returning Officer at the Guildhall, High Street, Bath, BA1 5AW, between 10am and 4pm on any working day after publication of this notice. Copies of the nomination papers can be downloaded from www.avonpccelection.org.uk Copies can also be requested either by calling 01225 477431 or by emailing [email protected] 3. Nomination papers must be hand delivered to the office of the Police Area Returning Officer at the Guildhall, High Street, Bath, BA1 5AW, between 10am and 4pm on any working day after publication of this notice but no later than 4pm on Thursday 8 April 2021. Candidates and agents are advised to book an appointment to submit their nomination papers, either by calling 01225 477431 or by emailing [email protected] 4. The £5,000 deposit can be paid: (a) by legal tender, or (b) by means of a banker’s draft from a drawer which carries on business as a banker in the United Kingdom, or (c) by electronic transfer of funds. 5. If the election is contested the poll will take place on Thursday 6 May 2021. 6. New applications to register to vote must reach the relevant Electoral Registration Officer (contact details below) by midnight on Monday 19 April 2021. Applications can be made online via www.gov.uk/register-to-vote 7. -

Disposal of Sharps

General information NEVER put sharps or a sharps container in your household rubbish Do not fill sharps containers with cotton wool, tissues etc. It should Advice on contain ONLY sharps Keep sharps and sharps containers disposal of away from children When the container is full (shown by a sharps line on the box) it should be ‘snapped’ shut If you need this leaflet in another format, eg. large print or a different language, please ask a member of staff. Yeovil District Hospital NHS Foundation Trust Higher Kingston Yeovil Somerset BA21 4AT 01935 475 122 Ref: 12-16-117 01935 475 122 yeovilhospital.nhs.uk Review: 03/18 yeovilhospital.nhs.uk Sharps containers can be obtained on When your container is full, call 0845 408 prescription from your GP. 2543 to ask for your details to be entered on their database. A contact number will then Sharps disposal be given to you. Use the contact number Arrangements for the safe disposal of your whenever you need a container collected. full sharps container which is used for insulin syringes, insulin pen needles and finger A new sharps bin is then usually issued, pricking lancets is dependant on where you but failing this, one can be obtained on live: prescription from your GP. South Somerset District Council Taunton Deane Borough Council South Somerset District Council runs an ‘on Taunton Deane Borough Council runs an demand’ collection service when your sharps ‘on demand’ collection service for full sharps container is full. containers. When full, call 01935 462462 to request When full, call 01823 356346 and ask for your collection of your sharps container sharps container to be collected and replaced with a new one. -

Somerset Geology-A Good Rock Guide

SOMERSET GEOLOGY-A GOOD ROCK GUIDE Hugh Prudden The great unconformity figured by De la Beche WELCOME TO SOMERSET Welcome to green fields, wild flower meadows, farm cider, Cheddar cheese, picturesque villages, wild moorland, peat moors, a spectacular coastline, quiet country lanes…… To which we can add a wealth of geological features. The gorge and caves at Cheddar are well-known. Further east near Frome there are Silurian volcanics, Carboniferous Limestone outcrops, Variscan thrust tectonics, Permo-Triassic conglomerates, sediment-filled fissures, a classic unconformity, Jurassic clays and limestones, Cretaceous Greensand and Chalk topped with Tertiary remnants including sarsen stones-a veritable geological park! Elsewhere in Mendip are reminders of coal and lead mining both in the field and museums. Today the Mendips are a major source of aggregates. The Mesozoic formations curve in an arc through southwest and southeast Somerset creating vales and escarpments that define the landscape and clearly have influenced the patterns of soils, land use and settlement as at Porlock. The church building stones mark the outcrops. Wilder country can be found in the Quantocks, Brendon Hills and Exmoor which are underlain by rocks of Devonian age and within which lie sunken blocks (half-grabens) containing Permo-Triassic sediments. The coastline contains exposures of Devonian sediments and tectonics west of Minehead adjoining the classic exposures of Mesozoic sediments and structural features which extend eastward to the Parrett estuary. The predominance of wave energy from the west and the large tidal range of the Bristol Channel has resulted in rapid cliff erosion and longshore drift to the east where there is a full suite of accretionary landforms: sandy beaches, storm ridges, salt marsh, and sand dunes popular with summer visitors.