Coral Triangle Marine Resources: Their Status, Economies, and Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State of the Coral Triangle: Solomon Islands

State of the Coral Triangle: Solomon Islands One of a series of six reports on the status of marine resources in the western Pacific Ocean, the State of the Coral Triangle: Solomon Islands describes the biophysical characteristics of Solomon Islands’ coastal and marine ecosystems, the manner in which they are being exploited, the framework in place that governs their use, the socioeconomic characteristics of the communities that use them, and the environmental threats posed by the manner in which STATE OF THE CORAL TRIANGLE: they are being used. It explains the country’s national plan of action to address these threats and improve marine resource management. Solomon Islands About the Asian Development Bank ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacific region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, it remains home to approximately two-thirds of the world’s poor: 1.6 billion people who live on less than $2 a day, with 733 million struggling on less than $1.25 a day. ADB is committed to reducing poverty through inclusive economic growth, environmentally sustainable growth, and regional integration. Based in Manila, ADB is owned by 67 members, including 48 from the region. Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, equity investments, guarantees, grants, and technical assistance. Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines www.adb.org Printed on recycled paper Printed in the Philippines STATE OF THE CORAL TRIANGLE: Solomon Islands © 2014 Asian Development Bank All rights reserved. -

The AREA's RICHNESS

The AREA’S RICHNESS hile there is little doubt that the Coral Triangle is the richest marine environment on the planet, the reasons for the richness are hotly debated. Is it because Wthe richest taxonomic groups originated in the Coral Triangle and dispersed to the rest of the world? Or is it because of the overlap of flora and fauna from the West Pacific Ocean and Indian Ocean? As it turns out, the only thing that is clear is that the reasons for the area’s richness are complex and no single model explains it all. Some of the many factors that influence the diversity of the Coral Triangle are the geological history of the region, including plate tectonics and sea-level fluctuations; how species disperse and the factors that facilitate or inhibit dispersal; general biogeographic patterns and evolutionary forces. The tropics are generally more species rich than temperate and polar areas particularly because of the constant sunlight regime and weather stability. Without a winter period, organisms can flourish year round and put more energy into specialization than into preparing for long periods with reduced sunlight. This is as true in the marine realm as it is in the forests, where light and relatively constant warm water temperatures persist throughout the year. However, coastal tropical waters are relatively nutrient poor. The annual changes in water temperatures of the temperate and polar seas produce mixing when the surface waters cool and sink to the bottom. The displaced bottom waters, rich with dead plankton that has sank to the depths, are forced to the surface and result in Due to ocean circulation patterns and the rotation of the Earth, As the glaciers melted and sea levels rose, the newly evolved species huge explosions of zooplankton and fish populations. -

SEDIMENTARY FRAMEWORK of Lmainland FRINGING REEF DEVELOPMENT, CAPE TRIBULATION AREA

GREAT BARRIER REEF MARINE PARK AUTHORITY TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM GBRMPA-TM-14 SEDIMENTARY FRAMEWORK OF lMAINLAND FRINGING REEF DEVELOPMENT, CAPE TRIBULATION AREA D.P. JOHNSON and RM.CARTER Department of Geology James Cook University of North Queensland Townsville, Q 4811, Australia DATE November, 1987 SUMMARY Mainland fringing reefs with a diverse coral fauna have developed in the Cape Tribulation area primarily upon coastal sedi- ment bodies such as beach shoals and creek mouth bars. Growth on steep rocky headlands is minor. The reefs have exten- sive sandy beaches to landward, and an irregular outer margin. Typically there is a raised platform of dead nef along the outer edge of the reef, and dead coral columns lie buried under the reef flat. Live coral growth is restricted to the outer reef slope. Seaward of the reefs is a narrow wedge of muddy, terrigenous sediment, which thins offshore. Beach, reef and inner shelf sediments all contain 50% terrigenous material, indicating the reefs have always grown under conditions of heavy terrigenous influx. The relatively shallow lower limit of coral growth (ca 6m below ADD) is typical of reef growth in turbid waters, where decreased light levels inhibit coral growth. Radiocarbon dating of material from surveyed sites confirms the age of the fossil coral columns as 33304110 ybp, indicating that they grew during the late postglacial sea-level high (ca 5500-6500 ybp). The former thriving reef-flat was killed by a post-5500 ybp sea-level fall of ca 1 m. Although this study has not assessed the community structure of the fringing reefs, nor whether changes are presently occur- ring, it is clear the corals present today on the fore-reef slope have always lived under heavy terrigenous influence, and that the fossil reef-flat can be explained as due to the mid-Holocene fall in sea-level. -

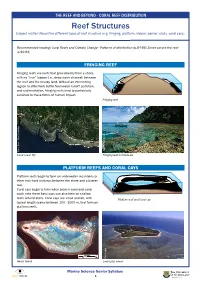

Reef Structures Subject Matter: Recall the Different Types of Reef Structure (E.G

THE REEF AND BEYOND - CORAL REEF DISTRIBUTION Reef Structures Subject matter: Recall the different types of reef structure (e.g. fringing, platform, ribbon, barrier, atolls, coral cays). Recommended reading: Coral Reefs and Climate Change - Patterns of distribution (p.84-85) Zones across the reef (p.92-94) FRINGING REEF Fringing reefs are reefs that grow directly from a shore, with no “true” lagoon (i.e., deep water channel) between the reef and the nearby land. Without an intervening lagoon to effectively buffer freshwater runoff, pollution, and sedimentation, fringing reefs tend to particularly sensitive to these forms of human impact. Fringing reef Tane Sinclair Taylor Tane Tane Sinclair Taylor Tane Planet Dove - Allen Coral Atlas Allen Coral Planet Dove - Coral coast, Fiji Fringing reef in Indonesia. PLATFORM REEFS AND CORAL CAYS Platform reefs begin to form on underwater mountains or other rock-hard outcrops between the shore and a barrier reef. Coral cays begin to form when broken coral and sand wash onto these flats; cays can also form on shallow reefs around atolls. Coral cays are small islands, with Platform reef and Coral cay typical length scales between 100 - 1000 m, that form on platform reefs, Dave Logan Heron Island Lady Elliot Island Marine Science Senior Syllabus 8 THE REEF AND BEYOND - CORAL REEF DISTRIBUTION Reef Structures BARRIER REEFS BARRIER REEFS are coral reefs roughly parallel to a RIBBON REEFS are a type of barrier reef and are unique shore and separated from it by a lagoon or other body of to Australia. The name relates to the elongated Reef water.The coral reef structure buffers shorelines against bodies starting to the north of Cairns, and finishing to the waves, storms, and floods, helping to prevent loss of life, east of Lizard Island. -

Delineating the Coral Triangle

Galaxea, Journal of Coral Reef Studies 11: 91-100(2009) Original paper Delineating the Coral Triangle J.E.N. VERON1, 2, *, Lyndon M. DEVANTIER1, 2, Emre TURAK1, 2, Alison L. GREEN3, Stuart KININMONTH2, Mary STAFFORD-SMITH1, and Nate PETERSON3 1 Coral Reef Research, 10 Benalla Road, Oak Valley, Townsville 4811, Australia 2 Australian Institute of Marine Science, MSO Townsville 4811, Australia 3 The Nature Conservancy, 51 Edmondstone Street, South Brisbane 4101, Australia * Corresponding author: J.E.N. Veron Email: [email protected] Communicated by Makoto Tsuchiya Abstract Spatial analyses of coral distributions at spe- Introduction cies level delineate the Coral Triangle and provide new insights into patterns of diversity and endemism around “If we look at a globe or a map of the Eastern Hemi the globe. This study shows that the Coral Triangle, an sphere, we shall perceive between Asia and Australia a area extending from the Philippines to the Solomon number of large and small islands, forming a connected Islands, has 605 zooxanthellate corals including 15 re- group distinct from those great masses of land and having gional endemics. This amounts to 76% of the world’s total little connexion with either of them. Situated upon the species complement, giving this province the world’s equator, and bathed in the tepid water of the great tropical highest conservation priority. Within the Coral Triangle, oceans, this region enjoys a climate more uniformly hot highest richness resides in the Bird’s Head Peninsula of and moist than almost any other part of the globe, and Indonesian Papua which hosts 574 species, with indi- teems with natural productions which are elsewhere vidual reefs supporting up to 280 species ha−1. -

The Fringing Reef Coasts of Eastern Africa—Present Processes in Their

Western Indian Ocean J. Mar.THE Sci. FRINGING Vol. 2, No. REEF 1, COASTSpp. 1–13, OF 2003 EASTERN AFRICA 1 © 2003 WIOMSA TheFringingReefCoastsofEasternAfrica—Present ProcessesinTheirLong-termContext RussellArthurton 5A Church Lane, Grimston, Melton Mowbray, Leicestershire LE14 3BY, UK Key words: Kenya, Tanzania, fringing reef, reef platform, sediment, sea-level change, climate variability, shoreline change, Late Pleistocene, Holocene Abstract—Sea-level changes through the Quaternary era have provided recurrent opportunities for the biosphere to significantly shape the coastal geomorphology of eastern Africa. Key agents in this shaping have been the calcium carbonate-fixing biota that have constructed the ocean- facing fringing reefs and produced the extensive backreef sediments that form the limestone platforms, cliffs and terraces that characterise these coasts. Today’s reefs comprise tough, algal- clad intertidal bars composed largely of coral rubble derived from their ocean front. They provide protection from wave attack to the inshore platforms with their sediment veneers and their beach and beach plain sands that are susceptible to erosion. If the eastern African coasts are subjected to the rise of sea-level that is predicted at the global scale during the coming century, the protective role of the reef bars will be diminished if their upward growth fails to keep pace. Favourable ocean temperatures and restraint in the destructive human pressures impacting the reef ecosystems will facilitate such growth. INTRODUCTION limestones). The wedges lap onto the much older rocks that form the continental margin and are Today’s eastern coast of Africa from Egypt to probably more than 100 m thick at their steep northern Mozambique is a reef coast, mostly ocean-facing edges (Fig. -

BIOT Field Report

©2015 Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Science Without Borders®. All research was completed under: British Indian Ocean Territory, The immigration Ordinance 2006, Permit for Visit. Dated 10th April, 2015, issued by Tom Moody, Administrator. This report was developed as one component of the Global Reef Expedition: BIOT research project. Citation: Global Reef Expedition: British Indian Ocean Territory. Field Report 19. Bruckner, A.W. (2015). Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation, Annapolis, MD. pp 36. The Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation (KSLOF) was incorporated in California as a 501(c)(3), public benefit, Private Operating Foundation in September 2000. The Living Oceans Foundation is dedicated to providing science-based solutions to protect and restore ocean health. For more information, visit http://www.lof.org and https://www.facebook.com/livingoceansfoundation Twitter: https://twitter.com/LivingOceansFdn Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation 130 Severn Avenue Annapolis, MD, 21403, USA [email protected] Executive Director Philip G. Renaud Chief Scientist Andrew W. Bruckner, Ph.D. Images by Andrew Bruckner, unless noted. Maps completed by Alex Dempsey, Jeremy Kerr and Steve Saul Fish observations compiled by Georgia Coward and Badi Samaniego Front cover: Eagle Island. Photo by Ken Marks. Back cover: A shallow reef off Salomon Atoll. The reef is carpeted in leather corals and a bleached anemone, Heteractis magnifica, is visible in the fore ground. A school of giant trevally, Caranx ignobilis, pass over the reef. Photo by Phil Renaud. Executive Summary Between 7 March 2015 and 3 May 2015, the Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation conducted two coral reef research missions as components of our Global Reef Expedition (GRE) program. -

A Guide for Vulnerability Assessment and Local Early Action Planning

Climate Change Adaptation for Coral Triangle Communities: A Guide for Vulnerability Assessment and Local Early Action Planning (LEAP Guide) The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID, NOAA or the US Government. This publication may be reproduced or quoted in other publications as long as proper reference is made to the source. The recommended citation is listed below. The U.S. Coral Triangle Initiative (US CTI) Support Program was established through the support of the U.S. Government to assist the leadership of the Coral Triangle countries to take action to maintain the coral reefs, fisheries, and food security of the Coral Triangle. US CTI is a coordinated effort of the Coral Triangle Support Partnership (CTSP, a consortium of World Wildlife Fund (WWF), Conservation International (CI), and The Nature Conservancy); the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA); the U.S. Department of State; and other partners. Spearheaded by the U.S. Agency for International Development Regional Development Mission Asia in collaboration with USAID/ Indonesia, USAID/ Philippines, and USAID/ Timor-Leste, the program assists the six countries of the Coral Triangle and the CTI Regional Secretariat to implement their Regional and National Plans of Action through technical assistance and capacity-building, and access to cutting-edge science. US CTI Support Program Document No. 11-USCTI-13 Suggested citation: U.S. Coral Triangle Initiative Support Program. (2013). Climate Change Adaptation for Coral Triangle Communities: Guide for Vulnerability Assessment and Local Early Action Planning (LEAP Guide). Prepared with support from the United States Agency for International Development. -

Identifying Gaps in the Coral Triangle Marine.Indd

IDENTIFYING GAPS IN THE CORAL TRIANGLE MARINE PROTECTED AREA SYSTEM AS CONSERVATION PRIORITIES This publication was prepared in cooperation with the Ministry of Maritime Affairs and Fisheries, with funding from the United States Agency for International Development’s Coral Triangle Support Partnership (2013) Cover photo: © Maria Beger IDENTIFYING GAPS IN THE CORAL TRIANGLE MARINE PROTECTED AREA SYSTEM AS CONSERVATION PRIORITIES October 2013 USAID Project Number GCP LWA # LAG-A-00-99-00048-00 Citation: Beger, M., J. McGowan, S. F. Heron, E. A. Treml, A. Green, A. T. White, N. H., Wolff, K. Hock, R. van Hooidonk, P. J. Mumby, and H. P. Possingham. 2013. Identifying conservation priority gaps in the Coral Triangle Marine Protected Area System. Coral Triangle Support Program of USAID, The Nature Conservancy, and The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia. This is a publication of the Coral Triangle Initiative on Coral Reefs, Fisheries, and Food Security (CTI-CFF). Funding for the preparation of this document was provided by the USAID-funded Coral Triangle Support Partnership (CTSP). CTSP is a consortium led by the World Wildlife Fund, The Nature Conservancy, and Conservation International with funding support from the United States Agency for International Development’s Regional Asia Program. For more information on the six-nation Coral Triangle Initiative, please contact: Coral Triangle Initiative on Coral Reefs, Fisheries, and Food Security Interim Regional Secretariat Ministry of Marine Affairs and Fisheries of the Republic of Indonesia Mina Bahari Building II, 17th Floor Jalan Medan Merdeka Timur No 16 Jakarta Pusat 10110 Indonesia www.thecoraltriangleintitiave.org © 2011 Coral Triangle Support Partnership. -

State of the Coral Triangle Report

oceans. All the main islands are volcanic in Executive Summary origin and are surrounded by barrier, patch, lagoonal, and fringing reefs. !us, the !e Solomon Islands National Plan of Action smaller islands are mostly raised coral (SI-NPOA): Coral Triangle Initiative on islands and atolls. Coral Reefs, Fisheries, and Food Security State of the (CTI-CFF) provides visionary guidance for !e climate in the Solomon Islands is the management of coral reefs and related characterized by a wet and a dry season. !e ecosystems in the Solomon Islands (Ministry mean temperature experienced all year round Coral of Environment, Climate Change, Disaster is 27°C (80°F), but with a few extremes of Management and Meteorology and warm and cold temperatures. !e southeast trade winds (ara) blow continuously with Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources, varying intensity during April to November, Triangle 2010). It is consistent with the CTI Regional while winds blow from west to northwest Plan of Action (RPOA), but also incorporates (koburu) from November to April. Tropical local situations and circumstances. Related cyclones and consequent strong winds are Report national initiatives, such as the Strategy for likely to occur from November to April. the Management of Inshore Fisheries and Marine Resources (Ministry of Fisheries and HIGHLIGHTS Marine Resources, 2010), complement the Biodiversity of coastal and actions outlined in the SI-NPOA. Another marine ecosystems important national initiative that !e Solomon Islands have one of the most complements the CTI NPOA is the diverse coral reef systems in the world. National Biodiversity Strategic and Action Such diversity is attributed to the highly Plan 2009. -

Biodiversity of the Caribbean

Biodiversity of the Caribbean A Learning Resource Prepared For: (Protecting the Eastern Caribbean Region’s Biodiversity Project) Photo supplied by: Andrew Ross (Seascape Caribbean) Part 2 / Section C Coral Reef Ecosystems February 2009 Prepared by Ekos Communications, Inc. Victoria, British Columbia, Canada [Part 2/Section C] Coral Reef Ecosystems Table of Contents C.1. What is a Coral Reef Ecosystem? C.2. Formation of Coral Reefs C.3. Types of Coral Reefs C.4. Species Biodiversity C.5. Importance of Coral Reefs C.5.a. Food Source and Habitat C.5.b. Water Filtration C.5.c. Fisheries C.5.d. Tourism C.5.e. Coastal Protection C.5.f. Source of Scientific Advances C.5.g. Intrinsic Value C.6. Types of Human & Natural Impacts C.6.a. Pollution C.6.b. Over-fishing C.6.c. Tourism C.6.d. Sedimentation C.6.e. Mining Reef Resources C.6.f. Climate Change C.7. Protecting Coral Reefs C.8. Student Fact Sheet: Fifty Facts About Wider Caribbean Coral Reefs C.9. Case Study: Tobago Cays Marine Park (TCMP), Southern Grenadines C.10. Activity 1: Mock Marine Management Plan C.11. Activity 2: Coral Reef Ecosystem Poster Presentation C.12. Case Study: Community-Based Natural Resource Management in the Bay Islands, Honduras C.13. Activity 3: Diagram the Case! C.14. References [Part 2/Section C] Coral Reef Ecosystems C.1. What is a Coral Reef Ecosystem? 30°C. Tropical corals are found within three main regions of the Coral reefs exist in the warm, clear, shallow waters of tropical world: the Indo-Pacific, the Western North Atlantic, and the Red oceans worldwide but also in the cold waters of the deep seas. -

Ancestral Genetic Diversity Associated with the Rapid Spread of Stress-Tolerant Coral Symbionts in Response to Holocene Climate Change

Ancestral genetic diversity associated with the rapid spread of stress-tolerant coral symbionts in response to Holocene climate change Benjamin C. C. Humea, Christian R. Voolstrab, Chatchanit Arifb, Cecilia D’Angeloa,c, John A. Burtd, Gal Eyale,f, Yossi Loyae, and Jörg Wiedenmanna,c,1 aCoral Reef Laboratory, Ocean and Earth Science, University of Southampton, Southampton SO14 3ZH, United Kingdom; bRed Sea Research Center, Division of Biological and Environmental Science and Engineering, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST), Thuwal 23955-6900, Saudi Arabia; cInstitute for Life Sciences, University of Southampton, Southampton SO17 1BJ, United Kingdom; dMarine Biology Laboratory, Centre for Genomics and Systems Biology, New York University Abu Dhabi, Abu Dhabi 129188, United Arab Emirates; eDepartment of Zoology, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv 6997801, Israel; and fThe Interuniversity Institute for Marine Sciences in Eilat, Eilat 8810369, Israel Edited by Nancy Knowlton, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, and approved March 3, 2016 (received for review February 4, 2016) Coral communities in the Persian/Arabian Gulf (PAG) withstand change from cooler and moister to warmer and more arid, reaching unusually high salinity levels and regular summer temperature today’s conditions only ∼4,000 y ago (8–10). Hence, the coral maxima of up to ∼35 °C that kill conspecifics elsewhere. Due to the communities of the PAG, composed mostly of a subset of Indian recent formation of the PAG and its subsequent shift to a hot cli- Ocean species (11), have had to adjust rapidly to temperatures not mate, these corals have had only <6,000 y to adapt to these ex- expected to occur in other parts of the world’soceansbeforethe treme conditions and can therefore inform on how coral reefs may next century (12).