80 Harding, Et Al. Silliman Journal Vol. 44 No. 2 2003 REEF CHECK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SEDIMENTARY FRAMEWORK of Lmainland FRINGING REEF DEVELOPMENT, CAPE TRIBULATION AREA

GREAT BARRIER REEF MARINE PARK AUTHORITY TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM GBRMPA-TM-14 SEDIMENTARY FRAMEWORK OF lMAINLAND FRINGING REEF DEVELOPMENT, CAPE TRIBULATION AREA D.P. JOHNSON and RM.CARTER Department of Geology James Cook University of North Queensland Townsville, Q 4811, Australia DATE November, 1987 SUMMARY Mainland fringing reefs with a diverse coral fauna have developed in the Cape Tribulation area primarily upon coastal sedi- ment bodies such as beach shoals and creek mouth bars. Growth on steep rocky headlands is minor. The reefs have exten- sive sandy beaches to landward, and an irregular outer margin. Typically there is a raised platform of dead nef along the outer edge of the reef, and dead coral columns lie buried under the reef flat. Live coral growth is restricted to the outer reef slope. Seaward of the reefs is a narrow wedge of muddy, terrigenous sediment, which thins offshore. Beach, reef and inner shelf sediments all contain 50% terrigenous material, indicating the reefs have always grown under conditions of heavy terrigenous influx. The relatively shallow lower limit of coral growth (ca 6m below ADD) is typical of reef growth in turbid waters, where decreased light levels inhibit coral growth. Radiocarbon dating of material from surveyed sites confirms the age of the fossil coral columns as 33304110 ybp, indicating that they grew during the late postglacial sea-level high (ca 5500-6500 ybp). The former thriving reef-flat was killed by a post-5500 ybp sea-level fall of ca 1 m. Although this study has not assessed the community structure of the fringing reefs, nor whether changes are presently occur- ring, it is clear the corals present today on the fore-reef slope have always lived under heavy terrigenous influence, and that the fossil reef-flat can be explained as due to the mid-Holocene fall in sea-level. -

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents Acknowledgements 1 Minister of Fisheries Opening Speech 2 Acronyms and Abbreviations 4 Executive Summary 5 1.0 Introduction 7 2.0 Background 9 2.1 The Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 9 2.2 The biological diversity of the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 11 3.0 Objectives of the FIME Biodiversity Visioning Workshop 13 3.1 Overall biodiversity conservation goals 13 3.2 Specifi c goals of the FIME biodiversity visioning workshop 13 4.0 Methodology 14 4.1 Setting taxonomic priorities 14 4.2 Setting overall biodiversity priorities 14 4.3 Understanding the Conservation Context 16 4.4 Drafting a Conservation Vision 16 5.0 Results 17 5.1 Taxonomic Priorities 17 5.1.1 Coastal terrestrial vegetation and small offshore islands 17 5.1.2 Coral reefs and associated fauna 24 5.1.3 Coral reef fi sh 28 5.1.4 Inshore ecosystems 36 5.1.5 Open ocean and pelagic ecosystems 38 5.1.6 Species of special concern 40 5.1.7 Community knowledge about habitats and species 41 5.2 Priority Conservation Areas 47 5.3 Agreeing a vision statement for FIME 57 6.0 Conclusions and recommendations 58 6.1 Information gaps to assessing marine biodiversity 58 6.2 Collective recommendations of the workshop participants 59 6.3 Towards an Ecoregional Action Plan 60 7.0 References 62 8.0 Appendices 67 Annex 1: List of participants 67 Annex 2: Preliminary list of marine species found in Fiji. 71 Annex 3 : Workshop Photos 74 List of Figures: Figure 1 The Ecoregion Conservation Proccess 8 Figure 2 Approximate -

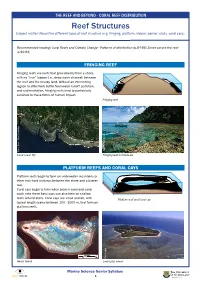

Reef Structures Subject Matter: Recall the Different Types of Reef Structure (E.G

THE REEF AND BEYOND - CORAL REEF DISTRIBUTION Reef Structures Subject matter: Recall the different types of reef structure (e.g. fringing, platform, ribbon, barrier, atolls, coral cays). Recommended reading: Coral Reefs and Climate Change - Patterns of distribution (p.84-85) Zones across the reef (p.92-94) FRINGING REEF Fringing reefs are reefs that grow directly from a shore, with no “true” lagoon (i.e., deep water channel) between the reef and the nearby land. Without an intervening lagoon to effectively buffer freshwater runoff, pollution, and sedimentation, fringing reefs tend to particularly sensitive to these forms of human impact. Fringing reef Tane Sinclair Taylor Tane Tane Sinclair Taylor Tane Planet Dove - Allen Coral Atlas Allen Coral Planet Dove - Coral coast, Fiji Fringing reef in Indonesia. PLATFORM REEFS AND CORAL CAYS Platform reefs begin to form on underwater mountains or other rock-hard outcrops between the shore and a barrier reef. Coral cays begin to form when broken coral and sand wash onto these flats; cays can also form on shallow reefs around atolls. Coral cays are small islands, with Platform reef and Coral cay typical length scales between 100 - 1000 m, that form on platform reefs, Dave Logan Heron Island Lady Elliot Island Marine Science Senior Syllabus 8 THE REEF AND BEYOND - CORAL REEF DISTRIBUTION Reef Structures BARRIER REEFS BARRIER REEFS are coral reefs roughly parallel to a RIBBON REEFS are a type of barrier reef and are unique shore and separated from it by a lagoon or other body of to Australia. The name relates to the elongated Reef water.The coral reef structure buffers shorelines against bodies starting to the north of Cairns, and finishing to the waves, storms, and floods, helping to prevent loss of life, east of Lizard Island. -

The Fringing Reef Coasts of Eastern Africa—Present Processes in Their

Western Indian Ocean J. Mar.THE Sci. FRINGING Vol. 2, No. REEF 1, COASTSpp. 1–13, OF 2003 EASTERN AFRICA 1 © 2003 WIOMSA TheFringingReefCoastsofEasternAfrica—Present ProcessesinTheirLong-termContext RussellArthurton 5A Church Lane, Grimston, Melton Mowbray, Leicestershire LE14 3BY, UK Key words: Kenya, Tanzania, fringing reef, reef platform, sediment, sea-level change, climate variability, shoreline change, Late Pleistocene, Holocene Abstract—Sea-level changes through the Quaternary era have provided recurrent opportunities for the biosphere to significantly shape the coastal geomorphology of eastern Africa. Key agents in this shaping have been the calcium carbonate-fixing biota that have constructed the ocean- facing fringing reefs and produced the extensive backreef sediments that form the limestone platforms, cliffs and terraces that characterise these coasts. Today’s reefs comprise tough, algal- clad intertidal bars composed largely of coral rubble derived from their ocean front. They provide protection from wave attack to the inshore platforms with their sediment veneers and their beach and beach plain sands that are susceptible to erosion. If the eastern African coasts are subjected to the rise of sea-level that is predicted at the global scale during the coming century, the protective role of the reef bars will be diminished if their upward growth fails to keep pace. Favourable ocean temperatures and restraint in the destructive human pressures impacting the reef ecosystems will facilitate such growth. INTRODUCTION limestones). The wedges lap onto the much older rocks that form the continental margin and are Today’s eastern coast of Africa from Egypt to probably more than 100 m thick at their steep northern Mozambique is a reef coast, mostly ocean-facing edges (Fig. -

BIOT Field Report

©2015 Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation. All Rights Reserved. Science Without Borders®. All research was completed under: British Indian Ocean Territory, The immigration Ordinance 2006, Permit for Visit. Dated 10th April, 2015, issued by Tom Moody, Administrator. This report was developed as one component of the Global Reef Expedition: BIOT research project. Citation: Global Reef Expedition: British Indian Ocean Territory. Field Report 19. Bruckner, A.W. (2015). Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation, Annapolis, MD. pp 36. The Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation (KSLOF) was incorporated in California as a 501(c)(3), public benefit, Private Operating Foundation in September 2000. The Living Oceans Foundation is dedicated to providing science-based solutions to protect and restore ocean health. For more information, visit http://www.lof.org and https://www.facebook.com/livingoceansfoundation Twitter: https://twitter.com/LivingOceansFdn Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation 130 Severn Avenue Annapolis, MD, 21403, USA [email protected] Executive Director Philip G. Renaud Chief Scientist Andrew W. Bruckner, Ph.D. Images by Andrew Bruckner, unless noted. Maps completed by Alex Dempsey, Jeremy Kerr and Steve Saul Fish observations compiled by Georgia Coward and Badi Samaniego Front cover: Eagle Island. Photo by Ken Marks. Back cover: A shallow reef off Salomon Atoll. The reef is carpeted in leather corals and a bleached anemone, Heteractis magnifica, is visible in the fore ground. A school of giant trevally, Caranx ignobilis, pass over the reef. Photo by Phil Renaud. Executive Summary Between 7 March 2015 and 3 May 2015, the Khaled bin Sultan Living Oceans Foundation conducted two coral reef research missions as components of our Global Reef Expedition (GRE) program. -

Musket-Compendium-2017.Pdf

1 2 Bula and welcome. On behalf of the Musket family we’d like to welcome you to paradise. At Musket Cove you’ll fnd the pace of life smooth and unhurried. Musket is the perfect location to relax and absorb island life. With plenty of space, activities, gourmet dining and over 170 warm and friendly staff here to welcome you to our island home. Vinaka vaka levu. Joe Mar and the team. Contents RESORT AND MARINA MAP 2 ABOUT MUSKET COVE 3 TIPS AND INFORMATION 4 - 9 EAT AND DRINK 10 DIVE INTO PARADISE WITH SUBSURFACE FIJI 11 - 12 ACTIVITIES AND THINGS TO DO 13 MUSKET EXCURIONS AND FISHING 14 MAKARE WELLNESS SPA 15 - 16 MUSKET ACCOMMODATION 17 MUSKET WEDDINGS AND EVENTS 18 A BETTER ENVIRONMENT 19 OUR PETS AND PESTS 20 FIJI LANGUAGE AND CULTURE 21 - 22 EMERGENCY AND SAFETY 23 - 24 SUPPLY OF SERVICES AND OBLIGATIONS 25 1 2 ABOUT MUSKET COVE Malolo Lailai the home of Musket Cove and is located in the Mamanuca group of Islands. You’ll fnd the pace of Island life a little slower than normal, just the way we like it, ensuring all the stresses you came with will be far from your mind by the time you leave. Malolo Lailai is 240 hectares with 10kms of palm fringed beaches and hiking trails. Getting here A leisurely 60 minute cruise from Port Denarau aboard the Malolo Cat, operating 4 dedicated return services daily. Private speedboat charters, seaplane or helicopter transfers can also be arranged. About us The resort is owned and operated by Fiji’s oldest resort company, recently celebrating 40 years’ in the Fijian hospitality industry. -

Mamanuca Sea Turtle Conservation Project

Mamanuca Sea Turtle Conservation Project mamanucammamamman maann ucucaa TTurttle Coonseerervaervationationn Biological Report Prrojecct October 2010 © Mamanuca Prepared by Merewalesi Laveti1 & Cherie Whippy-Morris Contents 1.0 Background 1 2.0 Introduction 4 3.0 Site Description 5 4.0 Methodology 5 4.1 Resource Mapping 5 4.2 Turtle Nesting 6 4.3 Nesting Beach Surveys 6 4.4 Foraging Ground Survey 7 5.0 Results 7 5.1 Resource Mapping 7 5.2 Nesting Turtle Surveys 9 5.3 Nesting Beach Surveys 10 5.4 Foraging Ground Surveys 13 6.0 Discussion 14 7.0 Conclusion 16 8.0 Recommendations 16 9.0 References 17 Acknowledgements 18 List of Figures Figure 1. The project site in the Mamanuca group of islands marked in dotted lines 5 Figure 2. Resource map showing turtle nesting, foraging and cultural taboo sites. 8 Figure 3. Two hawksbill turtle nests which was discovered on Navini Island in April 2010. 9 Figure 4. South Sea Island beach zones. 10 Figure 5. Tavarua Island beach zones. 10 Figure 6. Namotu Island beach zones. 11 Figure 7. Namotu island beach profile showing part of zones 1,3 and 4. 11 Figure 8. Sketch of Navini Island beach zones. 12 Figure 9. Seagrass species composition and percentage cover in Namotu in 2009. 13 Figure 10. Seagrass species composition and percentage cover in Namotu in 2010. 13 Figure 11. Namotu seagrass survey in April 2010. 13 List of Tables Table 1. Details of nesting surveys. 6 Table 2. The schedule of nesting beach surveys. 6 Table 3. Number of nesting turtles on selected sites in Mamanuca. -

Biodiversity of the Caribbean

Biodiversity of the Caribbean A Learning Resource Prepared For: (Protecting the Eastern Caribbean Region’s Biodiversity Project) Photo supplied by: Andrew Ross (Seascape Caribbean) Part 2 / Section C Coral Reef Ecosystems February 2009 Prepared by Ekos Communications, Inc. Victoria, British Columbia, Canada [Part 2/Section C] Coral Reef Ecosystems Table of Contents C.1. What is a Coral Reef Ecosystem? C.2. Formation of Coral Reefs C.3. Types of Coral Reefs C.4. Species Biodiversity C.5. Importance of Coral Reefs C.5.a. Food Source and Habitat C.5.b. Water Filtration C.5.c. Fisheries C.5.d. Tourism C.5.e. Coastal Protection C.5.f. Source of Scientific Advances C.5.g. Intrinsic Value C.6. Types of Human & Natural Impacts C.6.a. Pollution C.6.b. Over-fishing C.6.c. Tourism C.6.d. Sedimentation C.6.e. Mining Reef Resources C.6.f. Climate Change C.7. Protecting Coral Reefs C.8. Student Fact Sheet: Fifty Facts About Wider Caribbean Coral Reefs C.9. Case Study: Tobago Cays Marine Park (TCMP), Southern Grenadines C.10. Activity 1: Mock Marine Management Plan C.11. Activity 2: Coral Reef Ecosystem Poster Presentation C.12. Case Study: Community-Based Natural Resource Management in the Bay Islands, Honduras C.13. Activity 3: Diagram the Case! C.14. References [Part 2/Section C] Coral Reef Ecosystems C.1. What is a Coral Reef Ecosystem? 30°C. Tropical corals are found within three main regions of the Coral reefs exist in the warm, clear, shallow waters of tropical world: the Indo-Pacific, the Western North Atlantic, and the Red oceans worldwide but also in the cold waters of the deep seas. -

Coral Reef Ecosystem Research Plan Noaa for Fiscal Years 2007 to 2011

CORAL REEF ECOSYSTEM RESEARCH PLAN NOAA FOR FISCAL YEARS 2007 TO 2011 NOAA Technical Memorandum CRCP 1 CITATION: Puglise, K.A. and R. Kelty (eds.). 2007. NOAA Coral Reef Ecosystem Research Plan for Fiscal Years 2007 to 2011. Silver Spring, MD: NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program. NOAA Technical Memorandum CRCP 1. 128 pp. PLAN STEERING COMMITTEE: Gary Matlock and Barbara Moore (co-chairs) Eric Bayler, Andy Bruckner, Mark Eakin, Roger Griffis, Tom Hourigan, and David Kennedy FOR MORE INFORMATION: For more information about this report or to request a copy, please contact NOAA’s Coral Reef Conservation Program at 301-713-3155 or write to: NOAA Coral Reef Conservation Program; NOAA/NOS/OCRM; 1305 East West Highway; Silver Spring, MD 20910 or visit www.coralreef.noaa.gov. DISCLAIMER: Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation for their use by the United States government. NOAA Coral Reef Ecosystem Research Plan for Fiscal Years 2007 to 2011 K.A. Puglise and R. Kelty (eds.) National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration January 2007 NOAA Technical Memorandum CRCP 1 United States Department of National Oceanic and National Ocean Service Commerce Atmospheric Administration Carlos M. Gutierrez Conrad C. Lautenbacher, Jr. John H. Dunnigan Secretary Administrator Assistant Administrator ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We wish to express gratitude to all of the people, named and unnamed, who contributed to this Research Plan. This document truly represents the collective work of several individuals. In particular, -

Reef Check Australia South East Queensland Survey Season

Reef Check Australia Methods Manual Reef Check Foundation Ltd www.reefcheckaustralia.org CONTENTS REEF CHECK METHODS ....................................................................................................................... 2 THE TRANSECT LINE ............................................................................................................................ 2 SUBSTRATE SURVEY ............................................................................................................................ 4 INVERTEBRATE SURVEYS .................................................................................................................... 8 FISH SURVEYS ..................................................................................................................................... 9 REEF IMPACT SURVEYS ..................................................................................................................... 10 DATA ACCURACY .............................................................................................................................. 12 QUALITY ASSURANCE ....................................................................................................................... 12 WHAT HAPPENS TO THE DATA? ........................................................................................................ 14 HOW DO YOU INTERPRET REEF CHECK RESULTS? ............................................................................. 14 USEFUL REFERENCES ....................................................................................................................... -

Subsurface Fiji Dive Rates

SUBSURFACE FIJI DIVE RATES VALID FROM 1ST APRIL 2017 TO 31ST MARCH 2018 VALID AT MUSKET COVE, PLANTATION, LOMANI, LIKULIKU, MALOLO, TROPICA, NAVINI, WADIGI, TAVARUA, NAMOTU & FUNKY FISH ISLAND RESORTS. RATES QUOTED IN FIJI DOLLARS INCLUSIVE OF 25% GOVT TAXES CERTIFIED DIVER PACKAGES Night dive Number of Dives 1 2 3 4 6 8 10 (min 2 people) DIVE RATES (OWN GEAR) 175 310 460 600 870 1120 1340 215 DIVE RATES (RENTAL GEAR) 190 340 500 660 965 1245 1500 240 CERTIFIED DIVER PACKAGES INCLUDE TANK & WEIGHTS AND DIVEMASTER SERVICES. PROOF OF DIVE CERTIFICATION IS REQUIRED RENTAL EQUIPMENT INCLUDES BCD, REGULATOR, SUUNTO DIVE COMPUTER, WETSUIT, FINS, MASK & SNORKEL PADI DIVE COURSES PADI BUBBLE MAKER Children 8 – 12 yrs. Scuba diving in the pool. Incl Bubble Maker Certificate 130 SCUBA REVIEW Refresh your 21 PADI scuba skills with an Instructor in the pool. 180 PADI DISCOVER SCUBA Introductory dive experience in confined water (shore dive or pool )10yrs+ 160 PADI DISCOVER SCUBA DIVING Confined water dive, followed by ocean reef dive to 12 meters 10yrs+ 295 REPEAT DSD DIVE Ocean dive to maximum depth of 12 meter dive with a PADI Dive Master 220 PADI SCUBA DIVER Theory, in-pool sessions, 2 ocean dives, equipment & PADI certification 730 UPGRADE FROM SCUBA DIVER ...to Open Water Diver. Includes 2 dives, theory, equipment & PADI cert 620 PADI OPEN WATER DIVER Theory, in-pool training, 4 ocean dives, equipment & PADI certification 1120 PADI Open Water with online E-Learning already completed 960 PADI ADVENTURE DIVER Theory, 3 ocean dives, equipment and PADI certification 720 1 DIVE ADVENTURE/ADVANCED Rate for 1 Adventure dive, with PADI cert fee included, $415; without cert $260 PADI ADVANCED OPEN WATER Theory, 5 adventure ocean dives, equipment and PADI certification 1040 PADI Advanced OWC with online E-Learning already completed 890 PADI RESCUE DIVER Theory, confined water training skills, 3 ocean dives, PADI certification 890 EMERGENCY FIRST RESPONSE 1 Day. -

Status of Coral Reefs in the Fiji Islands 2007

COMPONENT 2A - Project 2A2 Knowledge, monitoring, management and beneficial use of coral reef ecosystems January 2009 REEF MONITORING SOUTH-WEST PACIFIC STATUS OF CORAL REEFS REPORT 2007 Edited by Cherrie WHIPPY-MORRIS Institute of Marine Resources With the support of: Photo: E. CLUA The CRISP programme is implemented as part of the Regional Environment Programme for a contribution to conservation and sustainable development of coral T (CRISP), sponsored by France and prepared by the French Development Agency (AFD) as part of an inter-ministerial project from 2002 onwards, aims to develop a vi- sion for the future of these unique eco-systems and the communities that depend on them and to introduce strategies and projects to conserve their biodiversity, while developing the economic and environmental services that they provide both locally and globally. Also, it is designed as a factor for integration between developed coun- - land developing countries. The CRISP Programme comprises three major components, which are: Component 1A: Integrated Coastal Management and watershed management - 1A1: Marine biodiversity conservation planning - 1A2: Marine Protected Areas - 1A3: Institutional strengthening and networking - 1A4: Integrated coastal reef zone and watershed management CRISP Coordinating Unit (CCU) Component 2: Development of Coral Ecosystems Programme manager : Eric CLUA - 2A: Knowledge, monitoring and management of coral reef ecosytems SPC - PoBox D5 - 2B: Reef rehabilitation 98848 Noumea Cedex - 2C: Development of active marine substances