Oil Spills in Coral Reefs PLANNING & RESPONSE CONSIDERATIONS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

7 Day Gbr Itinerary

7 DAY & 7 NIGHT GREAT BARRIER REEF ITINERARY PORT DOUGLAS | GREAT BARRIER REEF | COOKTOWN | LIZARD ISLAND PORT DOUGLAS Port Douglas is a town on the Coral Sea in the tropical far north of Queensland, Australia. Located a scenic 50 minute drive north of Cairns International airport, It's known for its luxury beach resorts and as a base for visits to both the Great Barrier Reef, the world's largest reef system, and Daintree National Park, home to biodiverse rainforest. In town, Macrossan Street is lined with boutique shops and restaurants. Curving south is popular Four Mile Beach. THE RIBBON REEFS - GREAT BARRIER REEF - Characteristically no wider than 450m, the Ribbon Reefs are part of the Great Barrier Reef Marina Park and are covered in colorful corals that attract a plethora of reef life big and small, with sandy gullies separating them, themselves containing interesting critters. The Ribbons reef host several of Australia’s most spectacular dive sites, as well as arguably the most prolific Black Marlin fishing in the world at certain times of year -with general fishing topping the list also. LIZARD ISLAND Lizard Island hosts Australia’s northernmost island resort. It is located 150 miles north of Cairns and 57 miles north east off the coast from Cooktown. Lizard Island is an absolute tropical paradise, a haven of isolation, gratification and relaxation. Accessible by boat and small aircraft, this tropical haven is a bucket list destination. Prominent dives spots on the Ribbon Reefs are generally quite shallow, with bommies coming up to as high as 5 metres below the surface from a sandy bottom that is between 15-20 metres below the surface. -

Coral Reef Education and Australian High School Students

CORAL REEF EDUCATION AND AUSTRALIAN HIGH SCHOOL STUDENTS by Carl M. Stepath, MEd PhD Candidate: School of Education, and School of Tropical Environment Studies & Geography; James Cook University, Cairns, Qld 4878, Australia, [email protected] In proceedings of the Marine Education Society of Australasia 2004 Conference, Noosa, Queensland, October 2-3, 2004. Keywords: tropical marine education, environmental and marine experiential education, environmental awareness and attitudes, ecological agency, coral reef education Abstract: This paper reports on a PhD research project investigating marine education in coral reef environments along the Queensland coast. The study explored relationships between awareness, attitudes and ecological skills of high school students who were trained in coral reef ecology and monitoring in offshore sites along the Great Barrier Reef in 2002 and 2003. The research investigated the question of whether experiential marine education can change the reported environmental knowledge, attitudes and ecological agency of student participants. Some key data outcomes are presented and implications for effective marine education strategies discussed. Introduction Educational programs that focus on humans and their relationship to coral reefs are becoming necessary, as reef structures along the Queensland coast come under mounting ecological pressure (GBRMPA, 2003; Hughes et al., 2003; Talbot, 1995). Marine education has been defined by Roseanne Fortner (1991) as that part of the total educational process that enables people to develop sensitivity to and a general understanding of the role of the seas in human affairs and the impact of society on the marine and aquatic environments. Improving pedagogical techniques concerning aquatic environments is valuable since continuing intensification of human activity near coastline areas adversely affects marine and coastal ecosystems worldwide (NOAA, 1998). -

An Assessment of Marine Ecosystem Damage from the Penglai 19-3 Oil Spill Accident

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article An Assessment of Marine Ecosystem Damage from the Penglai 19-3 Oil Spill Accident Haiwen Han 1, Shengmao Huang 1, Shuang Liu 2,3,*, Jingjing Sha 2,3 and Xianqing Lv 1,* 1 Key Laboratory of Physical Oceanography, Ministry of Education, Ocean University of China, Qingdao 266100, China; [email protected] (H.H.); [email protected] (S.H.) 2 North China Sea Environment Monitoring Center, State Oceanic Administration (SOA), Qingdao 266033, China; [email protected] 3 Department of Environment and Ecology, Shandong Province Key Laboratory of Marine Ecology and Environment & Disaster Prevention and Mitigation, Qingdao 266100, China * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.L.); [email protected] (X.L.) Abstract: Oil spills have immediate adverse effects on marine ecological functions. Accurate as- sessment of the damage caused by the oil spill is of great significance for the protection of marine ecosystems. In this study the observation data of Chaetoceros and shellfish before and after the Penglai 19-3 oil spill in the Bohai Sea were analyzed by the least-squares fitting method and radial basis function (RBF) interpolation. Besides, an oil transport model is provided which considers both the hydrodynamic mechanism and monitoring data to accurately simulate the spatial and temporal distribution of total petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH) in the Bohai Sea. It was found that the abundance of Chaetoceros and shellfish exposed to the oil spill decreased rapidly. The biomass loss of Chaetoceros and shellfish are 7.25 × 1014 ∼ 7.28 × 1014 ind and 2.30 × 1012 ∼ 2.51 × 1012 ind in the area with TPH over 50 mg/m3 during the observation period, respectively. -

Coral Reefs & Global Climate Change

environment+ + Coral reefs & Global climate change Potential Contributions of Climate Change to Stresses on Coral Reef Ecosystems + Robert W. Buddemeier KANSAS G EOLOGICAL S URVEY Joan A. Kleypas NATIONAL C ENTER FOR ATMOSPHERIC R ESEARCH Richard B. Aronson DAUPHIN I SLAND S EA L AB + Coral reefs & Global climate change Potential Contributions of Climate Change to Stresses on Coral Reef Ecosystems Prepared for the Pew Center on Global Climate Change by Robert W. Buddemeier KANSAS G EOLOGICAL S URVEY Joan A. Kleypas NATIONAL C ENTER FOR ATMOSPHERIC R ESEARCH Richard B. Aronson DAUPHIN I SLAND S EA L AB February 2004 Contents Foreword ii Executive Summary iii I. Introduction 1 A. Coral Reefs and Reef Organisms 1 B. The “Coral Reef Crisis” 4 C. Climate and Environmental Change 5 II. Nonclimatic Stresses to Coral Reefs 7 A. Types and Categories of Stresses and Effects 7 B. Terrestrial Inputs 9 C. Overfishing and Resource Extraction 11 D. Coastal Zone Modification and Mining 13 E. Introduced and Invasive Species 13 III. Climatic Change Stresses to Coral Reefs 14 A. Coral Bleaching 15 B. Global Warming and Reef Distribution 17 C. Reduced Calcification Potential 19 D. Sea Level 21 E. El Niño-Southern Oscillation 21 F. Ocean Circulation Changes 22 + G. Precipitation and Storm Patterns 22 IV. Synthesis and Discussion 24 A. Infectious Diseases 24 B. Predation 25 C. Connections with Global Climate Change and Human Activity 26 D. Regional Comparison 27 E. Adaptation 28 V. Resources at Risk 30 + A. Socioeconomic Impacts 30 B. Biological and Ecological Impacts 31 C. Protection and Conservation 31 VI. -

Hawai'i Institute of Marine Biology Northwestern Hawaiian Islands

Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Research Partnership Quarterly Progress Reports II-III August, 2005-March, 2006 Report submitted by Malia Rivera and Jo-Ann Leong April 21, 2006 Photo credits: Front cover and back cover-reef at French Frigate Shoals. Upper left, reef at Pearl and Hermes. Photos by James Watt. Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Research Partnership Quarterly Progress Reports II-III August, 2005-March, 2006 Report submitted by Malia Rivera and Jo-Ann Leong April 21, 2006 Acknowledgments. Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB) acknowledges the support of Senator Daniel K. Inouye’s Office, the National Marine Sanctuary Program (NMSP), the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve (NWHICRER), State of Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR) Division of Aquatic Resources, US Fish and Wildlife Service, NOAA Fisheries, and the numerous University of Hawaii partners involved in this project. Funding provided by NMSP MOA 2005-008/66832. Photos provided by NOAA NWHICRER and HIMB. Aerial photo of Moku o Lo‘e (Coconut Island) by Brent Daniel. Background The Hawai‘i Institute of Marine Biology (School of Ocean and Earth Science and Technology, University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa) signed a memorandum of agreement with National Marine Sanctuary Program (NOS, NOAA) on March 28, 2005, to assist the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands Coral Reef Ecosystem Reserve (NWHICRER) with scientific research required for the development of a science-based ecosystem management plan. With this overriding objective, a scope of work was developed to: 1. Understand the population structures of bottomfish, lobsters, reef fish, endemic coral species, and adult predator species in the NWHI. -

SEDIMENTARY FRAMEWORK of Lmainland FRINGING REEF DEVELOPMENT, CAPE TRIBULATION AREA

GREAT BARRIER REEF MARINE PARK AUTHORITY TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM GBRMPA-TM-14 SEDIMENTARY FRAMEWORK OF lMAINLAND FRINGING REEF DEVELOPMENT, CAPE TRIBULATION AREA D.P. JOHNSON and RM.CARTER Department of Geology James Cook University of North Queensland Townsville, Q 4811, Australia DATE November, 1987 SUMMARY Mainland fringing reefs with a diverse coral fauna have developed in the Cape Tribulation area primarily upon coastal sedi- ment bodies such as beach shoals and creek mouth bars. Growth on steep rocky headlands is minor. The reefs have exten- sive sandy beaches to landward, and an irregular outer margin. Typically there is a raised platform of dead nef along the outer edge of the reef, and dead coral columns lie buried under the reef flat. Live coral growth is restricted to the outer reef slope. Seaward of the reefs is a narrow wedge of muddy, terrigenous sediment, which thins offshore. Beach, reef and inner shelf sediments all contain 50% terrigenous material, indicating the reefs have always grown under conditions of heavy terrigenous influx. The relatively shallow lower limit of coral growth (ca 6m below ADD) is typical of reef growth in turbid waters, where decreased light levels inhibit coral growth. Radiocarbon dating of material from surveyed sites confirms the age of the fossil coral columns as 33304110 ybp, indicating that they grew during the late postglacial sea-level high (ca 5500-6500 ybp). The former thriving reef-flat was killed by a post-5500 ybp sea-level fall of ca 1 m. Although this study has not assessed the community structure of the fringing reefs, nor whether changes are presently occur- ring, it is clear the corals present today on the fore-reef slope have always lived under heavy terrigenous influence, and that the fossil reef-flat can be explained as due to the mid-Holocene fall in sea-level. -

What Evidence Exists on the Impacts of Chemicals Arising from Human Activity on Tropical Reef-Building Corals?

Ouédraogo et al. Environ Evid (2020) 9:18 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13750-020-00203-x Environmental Evidence SYSTEMATIC MAP PROTOCOL Open Access What evidence exists on the impacts of chemicals arising from human activity on tropical reef-building corals? A systematic map protocol Dakis‑Yaoba Ouédraogo1* , Romain Sordello2, Sophie Brugneaux3, Karen Burga4, Christophe Calvayrac5,6, Magalie Castelin7, Isabelle Domart‑Coulon8, Christine Ferrier‑Pagès9, Mireille M. M. Guillaume10,11, Laetitia Hédouin11,12, Pascale Joannot13, Olivier Perceval14 and Yorick Reyjol2 Abstract Background: Tropical coral reefs cover ca. 0.1% of the Earth’s surface but host an outstanding biodiversity and provide important ecosystem services to millions of people living nearby. However, they are currently threatened by both local (e.g. nutrient enrichment and chemical pollution of coastal reefs, arising from poor land management, agriculture and industry) and global stressors (mainly seawater warming and acidifcation, i.e. climate change). Global and local stressors interact together in diferent ways, but the presence of one stressor often reduces the tolerance to additional stress. While global stressors cannot be halted by local actions, local stressors can be reduced through ecosystem management, therefore minimizing the impact of climate change on reefs. To inform decision‑makers, we propose here to systematically map the evidence of impacts of chemicals arising from anthropogenic activities on tropical reef‑building corals, which are the main engineer species of reef ecosystems. We aim to identify the combina‑ tions of chemical and coral responses that have attracted the most attention and for which evidence can be further summarized in a systematic review that will give practical information to decision‑makers. -

Molasses Reef Sanctuary Preservation Area

Molasses Reef Sanctuary Preservation Area SANCTUARY AREAS Wellwood Restoration Research Sand Only Ecological Reserve Existing Management Area Sanctuary Preservation Area Sand (SPAs) Wildlife Lighted Management Area Marker 10 Shallow Sea Grass Rubble Shallow Coral Sand 25' 35' Very Shallow Island 5' 18” Mooring Buoy 3 - 5ft. 40'-50' Spar Buoy 30” Yellow Sanctuary Buoy FKNMS Shipwreck Trail A Boating and Angling Guide to the Molasses Reef Sanctuary Preservation Area With certain exceptions, the following activities are prohibited Sanctuary-Wide: • Moving, removing, taking, injuring, touching, breaking, • Operating a vessel at more than 4 knots/no wake cutting or possessing coral or live rock. within 100 yards of a “divers down” flag. • Discharging or depositing treated or untreated sewage • Diving or snorkeling without a dive flag. from marine sanitation devices, trash and other • Operating a vessel in such a manner which endangers materials life, limb, marine resources, or property. • Dredging, drilling, prop dredging or otherwise altering • Releasing exotic species. the seabed, or placing or abandoning any structure on • Damaging or removing markers, mooring buoys, the seabed. scientific equipment, boundary buoys, and trap buoys. • Operating a vessel in such a manner as to strike or • Moving, removing, injuring, or possessing historical otherwise injure coral, seagrass, or other immobile resources. organisms attached to the seabed, or cause prop • Taking or possessing protected wildlife. scarring. • Using or possessing explosives or electrical charges. • Having a vessel anchored on living coral in water less • Harvesting, possessing or landing any marine life than 40 feet deep when the bottom can be seen. species except as allowed by the Florida Fish and Anchoring on hardbottom is allowed. -

Persistent Organic Pollutants in Marine Plankton from Puget Sound

Control of Toxic Chemicals in Puget Sound Phase 3: Persistent Organic Pollutants in Marine Plankton from Puget Sound 1 2 Persistent Organic Pollutants in Marine Plankton from Puget Sound By James E. West, Jennifer Lanksbury and Sandra M. O’Neill March, 2011 Washington Department of Ecology Publication number 11-10-002 3 Author and Contact Information James E. West Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife 1111 Washington St SE Olympia, WA 98501-1051 Jennifer Lanksbury Current address: Aquatic Resources Division Washington Department of Natural Resources (DNR) 950 Farman Avenue North MS: NE-92 Enumclaw, WA 98022-9282 Sandra M. O'Neill Northwest Fisheries Science Center Environmental Conservation Division 2725 Montlake Blvd. East Seattle, WA 98112 Funding for this study was provided by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, through a Puget Sound Estuary Program grant to the Washington Department of Ecology (EPA Grant CE- 96074401). Any use of product or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the authors or the Department of Fish and Wildlife. 4 Table of Contents Table of Contents................................................................................................................................................... 5 List of Figures ....................................................................................................................................................... 7 List of Tables ....................................................................................................................................................... -

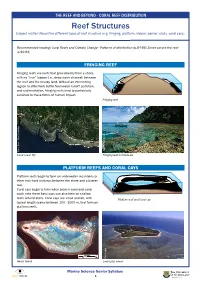

Reef Structures Subject Matter: Recall the Different Types of Reef Structure (E.G

THE REEF AND BEYOND - CORAL REEF DISTRIBUTION Reef Structures Subject matter: Recall the different types of reef structure (e.g. fringing, platform, ribbon, barrier, atolls, coral cays). Recommended reading: Coral Reefs and Climate Change - Patterns of distribution (p.84-85) Zones across the reef (p.92-94) FRINGING REEF Fringing reefs are reefs that grow directly from a shore, with no “true” lagoon (i.e., deep water channel) between the reef and the nearby land. Without an intervening lagoon to effectively buffer freshwater runoff, pollution, and sedimentation, fringing reefs tend to particularly sensitive to these forms of human impact. Fringing reef Tane Sinclair Taylor Tane Tane Sinclair Taylor Tane Planet Dove - Allen Coral Atlas Allen Coral Planet Dove - Coral coast, Fiji Fringing reef in Indonesia. PLATFORM REEFS AND CORAL CAYS Platform reefs begin to form on underwater mountains or other rock-hard outcrops between the shore and a barrier reef. Coral cays begin to form when broken coral and sand wash onto these flats; cays can also form on shallow reefs around atolls. Coral cays are small islands, with Platform reef and Coral cay typical length scales between 100 - 1000 m, that form on platform reefs, Dave Logan Heron Island Lady Elliot Island Marine Science Senior Syllabus 8 THE REEF AND BEYOND - CORAL REEF DISTRIBUTION Reef Structures BARRIER REEFS BARRIER REEFS are coral reefs roughly parallel to a RIBBON REEFS are a type of barrier reef and are unique shore and separated from it by a lagoon or other body of to Australia. The name relates to the elongated Reef water.The coral reef structure buffers shorelines against bodies starting to the north of Cairns, and finishing to the waves, storms, and floods, helping to prevent loss of life, east of Lizard Island. -

Statistical Mechanics I: Exam Review 1 Solution

8.333: Statistical Mechanics I Fall 2007 Test 1 Review Problems The first in-class test will take place on Wednesday 9/26/07 from 2:30 to 4:00 pm. There will be a recitation with test review on Friday 9/21/07. The test is ‘closed book,’ but if you wish you may bring a one-sided sheet of formulas. The test will be composed entirely from a subset of the following problems. Thus if you are familiar and comfortable with these problems, there will be no surprises! ******** You may find the following information helpful: Physical Constants 31 27 Electron mass me 9.1 10− kg Proton mass mp 1.7 10− kg ≈ × 19 ≈ × 34 1 Electron Charge e 1.6 10− C Planck’s const./2π ¯h 1.1 10− Js− ≈ × 8 1 ≈ × 8 2 4 Speed of light c 3.0 10 ms− Stefan’s const. σ 5.7 10− W m− K− ≈ × 23 1 ≈ × 23 1 Boltzmann’s const. k 1.4 10− JK− Avogadro’s number N 6.0 10 mol− B ≈ × 0 ≈ × Conversion Factors 5 2 10 4 1atm 1.0 10 Nm− 1A˚ 10− m 1eV 1.1 10 K ≡ × ≡ ≡ × Thermodynamics dE = T dS+dW¯ For a gas: dW¯ = P dV For a wire: dW¯ = Jdx − Mathematical Formulas √π ∞ n αx n! 1 0 dx x e− = αn+1 2 ! = 2 R 2 2 2 ∞ x √ 2 σ k dx exp ikx 2σ2 = 2πσ exp 2 limN ln N! = N ln N N −∞ − − − →∞ − h i h i R n n ikx ( ik) n ikx ( ik) n e− = ∞ − x ln e− = ∞ − x n=0 n! � � n=1 n! � �c P 2 4 P 3 5 cosh(x) = 1 + x + x + sinh(x) = x + x + x + 2! 4! · · · 3! 5! · · · 2πd/2 Surface area of a unit sphere in d dimensions Sd = (d/2 1)! − 1 1. -

Reef Restoration Concepts & Guidelines: Making Sensible Management Choices in the Face of Uncertainty

Reef Restoration Concepts & Guidelines: Making sensible management choices in the face of uncertainty. by Alasdair Edwards and Edgardo Gomez www.gefcoral.org Alasdair J. Edwards1 and Edgardo D. Gomez2 1 Division of Biology, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne NE1 7RU, United Kingdom 2 Marine Science Institute, University of the Philippines, 1101 Quezon City, Philippines The views are those of the authors who acknowledge their debt to other members of the Restoration and Remediation Working Group (RRWG) of the Coral Reef Targeted Research & Capacity Building for Management project for ideas, information and lively discussion of reef restoration concepts, issues and techniques. We thank Richard Dodge, Andrew Heyward, Tadashi Kimura, Chou Loke Ming, Aileen Morse, Makoto Omori, and Buki Rinkevich for their free exchange of views. We thank Marea Hatziolos, Andy Hooten, James Guest and Chris Muhando for valuable comments on the text. Finally, we thank the Coral Reef Initiative for the South Pacific (CRISP), Eric Clua, Sandrine Job and Michel Porcher for providing details of restoration projects for the section on “Learning lessons from restoration projects”. Publication data: Edwards, A.J., Gomez, E.D. (2007). Reef Restoration Concepts and Guidelines: making sensible management choices in the face of uncertainty. Coral Reef Targeted Research & Capacity Building for Management Programme: St Lucia, Australia. iv + 38 pp. Published by: The Coral Reef Targeted Research & Capacity Building for Management Program Postal address: Project Executing Agency Centre for Marine Studies Level 7 Gerhmann Building The University of Queensland St Lucia QLD 4072 Australia Telephone: +61 7 3346 9942 Facsimile: +61 7 3346 9987 E-mail: [email protected] Internet: www.gefcoral.org The Coral Reef Targeted Research & Capacity Building for Management (CRTR) Program is a leading international coral reef research initiative that provides a coordinated approach to credible, factual and scientifically-proven knowledge for improved coral reef management.