Mamanuca Sea Turtle Conservation Project

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why Book with Rosie Holidays?

F i j i GROUND OPERATOR OF THE YEAR 2015/16 SINCE 2002 Why Book With Rosie Holidays? PEACE OF MIND QUALITY ALL THE WAY 25 YEARS EXPERIENCE All accommodation featured in We pride ourselves on delivering We know Fiji, and our travel 1 this guide has been visited and 2 first class customer service, from 3 specialists will help you create personally checked by our travel planning and booking, right your perfect holiday. experts, so you can buy quality through to peace of mind while with confidence. you are travelling. A SUPERB RANGE EARN MYER one FEEJEE DISCOUNT CARD This guide features over 55 hotels, SHOPPING CREDITS ON The Feejee Discount card gives boutique properties, resorts, tours, you discounts and exclusive 4 5 YOUR HOLIDAY 6 cruises and sightseeing options to shopping offers at over 15 Book with Rosie Holidays and earn suit every need. Check out pages outlets, including restaurants, one Shopping Credit for every 6 and 7 for recommendations duty-free outlets, handicraft and dollar you spend on your holiday! based on your traveller type. fashion stores, and a beauty spa. AIRLINE PARTNER Fiji Airways has been connecting the world to Fiji, the South Pacific and beyond for over 60 years. Travellers from Australia will find convenient flights departing to Fiji and beyond from Sydney, Melbourne and Brisbane, offering world-class service in both Business and Economy class. Fiji Airways is also a partner in the Qantas Frequent Flyer programme and members can earn and redeem points as well as credit flights towards tier status. Formerly Air Pacific, the airline returned to its 1958 name of Fiji Airways in June 2013, introducing a brand new fleet of Airbus 330-200 aircraft and an enhanced in-flight experience. -

Mamanuca & Yasawa Groups

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Mamanuca & Yasawa Groups Includes ¨ Why Go? Bounty Island .......118 They’re but a streak on the map, the 50-odd islands that Beachcomber Island ..119 make up the Mamanuca and Yasawa groups are a behemoth Mana ...............120 of beauty that pack a powerful – and paradisiacal – punch. Though they’re easily accessible from Nadi, the region is Matamanoa .........122 home to everything far-flung-tropical-island daydreams are Modriki .............122 made of: rustling palms, obscenely blue waters, blinding Castaway Island .....123 white sands and local smiles just as bright. Incredibly, this Malolo ..............123 eden is open to all; no matter your budget, you’ll find quality Kuata & Wayasewa ...128 accommodation and million-dollar views. The 20 or so picture-perfect coral atolls and islands of the Waya & Around ......130 Mamanucas arc west through the large lagoon formed by the Malolo Barrier Reef and Viti Levu. It’s a treasure trove of surf breaks, sea turtles, reef sharks and vast schools of Best Places to Eat multicoloured tropical fish. To the north, the volcanic islands of the Yasawas reward ¨ Navutu Stars (p133) visitors with blue lagoons, exquisite beaches, technicolour ¨ Mantaray Island coral gardens and craggy landscapes aching to be explored. Resort (p132) ¨ Botaira Beach Resort (p133) When to Go ¨ Travellers Tea House Mamanuca & Yasawa Groups (p136) °C/°F Te mp Rainfall inches/mm 40/104 16/400 12/300 Best Places to 30/86 Stay 8/200 ¨ 20/68 Coconut Beach Resort 4/100 (p135) ¨ Beachcomber Island 10/50 0 J FDM A M J J A S O N Resort (p119) ¨ Blue Lagoon Beach May–Oct Gen- Oct–Dec Fewer Jan–Mar Steamy Resort (p136) erally sunny travellers, greater green wet season; dry days, with choice of accom- expect some ¨ Navini Island cool(ish) nights modation; evening transport delays Resort (p120) that make for rainstorms and in stormy weather. -

VAT-Registrant-As-At-31St-August

TIN TAXPAYER NAME REGISTRATION 0070125412 ADILAXMI 10/Nov/00 0183020604 SUBARMANI 26/Apr/04 0505512103 06 INVESTMENT SERVICES AND CONSULTANCY 27/Mar/17 0501576608 14 TAUNOVO BAY, LLC PTE LIMITED 2/Feb/06 0505215206 180-16 SOUTH PTE LIMITED 14/Oct/14 0505801401 2 FRANGIPANIS PTE LTD 15/Mar/19 0501744403 21ST AGENCY PTE LIMITED 26/Jan/09 0501106902 231 WAIMANU RD HOLDINGS PTE LIMITED 1/Jan/99 2900090495 27 DEGREES CATERING MANAGEMENT PTE LTD . 10/Dec/19 0505273408 3 DIMENSION CONSULTANS (FIJI) PTE 9/Jan/15 0505784201 3 HUNGRY BEARS BAR & GRILL PTE LTD 24/Jan/19 0306211405 3 PIZ RESTAURANT 30/Sep/19 0306164608 3 SIXTY FASHIONS 7/Aug/17 2900081341 360 ENERGY PTE LIMITED . 20/Jan/20 0505587707 360 EVENTS (FIJI) PTE LTD 25/Oct/17 2900083334 360 SERVICES PTE LIMITED . 20/Jan/20 0505258005 3SA CARPETS PTE LIMITED 20/Sep/12 0300935105 4 U SPARES 20/Feb/09 0501412605 4 WHEEL DRIVE SALES PTE LIMITED 14/Feb/03 0501474203 44 MAGNUM PRODUCTIONS PTE LIMITED 5/May/04 0508490907 480 HOLDINGS PTE LIMITED 13/Jan/12 0501694407 4S SHOES PTE LIMITED 31/Dec/07 0505747006 5 GOLDEN CIRCLES PTE LTD 6/Sep/18 0750005403 5 M TRUST 29/Aug/05 2900112773 7 NAQURA FARM PTE LIMITED 11/Mar/20 0505861306 786 CIVIL CONTRACTORS PTE LTD 22/Oct/19 0505647809 786 HYPER MART PTE LTD 21/Nov/17 0505581804 78692 HALAAL SUPERMARKET PTE LTD 6/Oct/17 0501606206 88 BIG RESTAURANT PTE LIMITED 12/Jul/06 0505226808 88STEPS PTE LIMITED 24/Nov/14 0505321907 9 CHINA INTERNATIONAL TOURISM COMPANY 19/Jun/15 0505298409 9 CHINA GROUP COMPANY LIMITED 23/Mar/15 0505197706 99 BOUTIQUE IMPORT AND -

HELLO FIJI Helloworld Is a Fresh New Travel Brand with a Long and Solid History

2017 HELLO FIJI helloworld is a fresh new travel brand with a long and solid history. We have previously created lasting travel memories for clients as Harvey World Travel, selected stores from the United Travel group and Air New Zealand Holidays brands. Allow us to share our knowledge, passion and expertise with you. Our mission is to offer New Zealand travellers industry leading service and deliver the best value holidays. With helloworld, you can plan your holiday at your convenience with our nationwide network of stores and comprehensive website. Our people are truly passionate about travel and can’t wait to share their expertise. Our helloworld store owners and their teams have a genuine interest in making your travel enjoyable and hassle free. As experienced travellers ourselves, we know what goes into making your holiday great and will go the extra mile to make sure your next holiday is your best one yet. We’re helloworld - nice to meet you! South Sea Island | 28 Nadi | 51 Mamanuca Islands | 56 Valid 1 April 2017 – 31 March 2018. Image Right: Malolo Island Contents Navigating This Brochure 4 Travel Tips 6 Accommodation Index 7 Top 10 Things To Do 8 Planning Your Fiji Holiday 11 Fiji Holiday Packages 12 Family Holidays 12 Spa and Relaxation Holidays 13 Adventure Holidays 14 Romantic Getaways 15 Fiji Weddings 16 Exploring Fiji 18 Car Hire 18 Island Adventures 19 Island Cruising 22 Island Transfers 24 Sightseeing 27 Denarau Island 31 Coral Coast & Pacific Coast 37 Regional Fiji 46 Nadi & Surrounds 51 Mamanuca Islands 56 Yasawa Islands 67 Regional Fiji Islands 71 Booking Conditions 75 3 Navigating This Brochure 2017 2017 Let helloworld inspire HELLO HELLO ADELAIDE GOLD & SOUTH COAST you to discover these AUSTRALIA Accommodation Ratings fantastic destinations Diamond ratings are used throughout the brochure to describe the standard of accommodation. -

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents Acknowledgements 1 Minister of Fisheries Opening Speech 2 Acronyms and Abbreviations 4 Executive Summary 5 1.0 Introduction 7 2.0 Background 9 2.1 The Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 9 2.2 The biological diversity of the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 11 3.0 Objectives of the FIME Biodiversity Visioning Workshop 13 3.1 Overall biodiversity conservation goals 13 3.2 Specifi c goals of the FIME biodiversity visioning workshop 13 4.0 Methodology 14 4.1 Setting taxonomic priorities 14 4.2 Setting overall biodiversity priorities 14 4.3 Understanding the Conservation Context 16 4.4 Drafting a Conservation Vision 16 5.0 Results 17 5.1 Taxonomic Priorities 17 5.1.1 Coastal terrestrial vegetation and small offshore islands 17 5.1.2 Coral reefs and associated fauna 24 5.1.3 Coral reef fi sh 28 5.1.4 Inshore ecosystems 36 5.1.5 Open ocean and pelagic ecosystems 38 5.1.6 Species of special concern 40 5.1.7 Community knowledge about habitats and species 41 5.2 Priority Conservation Areas 47 5.3 Agreeing a vision statement for FIME 57 6.0 Conclusions and recommendations 58 6.1 Information gaps to assessing marine biodiversity 58 6.2 Collective recommendations of the workshop participants 59 6.3 Towards an Ecoregional Action Plan 60 7.0 References 62 8.0 Appendices 67 Annex 1: List of participants 67 Annex 2: Preliminary list of marine species found in Fiji. 71 Annex 3 : Workshop Photos 74 List of Figures: Figure 1 The Ecoregion Conservation Proccess 8 Figure 2 Approximate -

A Piece of Their Identity - Fiji Times Online Fijitimes.Com

http://www.fijitimes.com/story.aspx?id=375767 A piece of their identity - Fiji Times Online fijitimes.com Sikeli Qounadovu Sunday, October 23, 2016 + Enlarge this image Sunset over Monu and Monuriki Island. Picture: SIKELI QOUNADOVU WHEN they were young, they feared going to Monuriki Island because according to their elders it was haunted by a monster with strange looking claws and razor sharp teeth. Back then, children of Yanuya Village were scared to travel to the island, for fear of being eaten alive by the monster. Sunset over Monu and Monuriki Island. Picture: SIKELI QOUNADOVU That was the story shared by Semisi Naceva, the leader of the tokatoka Vunaivira. This week, we take you on a new journey of discovery. We find out more about Monuriki Island, and how its habitat, one of the country's endemic species, is now earmarked as an income generating project. It is a discovery of the western banded crested iguana that is only found on the island. What was first thought of as a monster is, according to Mr Naceva, one of the friendliest species. Monuriki is an uninhabited tiny island off the west coast of Viti Levu in a group of islands known as the Mamanuca Islands. Monuriki is a five-minute boat ride from the nearest village of Yanuya on the island of Yanuya. The island is of volcanic origin and is a 38-acre haven with steep rocky terrain rising to more than 200 metres above sea level. Garlanded by white sandy beach and crystal clear waters that glitter like a sea of diamond, Monuriki is home to the crested iguana that is only found in Fiji. -

Fiji Welcomes Investors

2005 Fiji Welcomes Investors Author – Deborah Keller Senior Associate HVS International – Sydney, Australia HVS INTERNATIONAL SYDNEY Level 1, 5 Elizabeth Street Sydney NSW 2000 Australia Tel: (61) 02 - 9233 1125 Fax: (61) 02 – 9233 1147 Email: [email protected] Web: www.hvsinternational.com Sydney Singapore Hong Kong London Madrid New Delhi São Paulo Buenos Aires New York San Francisco Boulder Denver Miami Dallas Chicago Washington, D.C. Weston, CT Phoenix Mt. Lakes, NJ Vancouver Toronto Fiji is emerging as the hot spot in the Pacific. Tourist arrivals are booming and many resorts are reaching full capacity. The introduction of low cost airlines, coupled with the appeal of Fiji as both a safe haven and one of the few remaining unspoiled tourist destinations is driving demand. Developers and investors appear enthusiastic about market prospects. This enthusiasm is also being stimulated by the Fiji Government, which is offering generous financial and tax incentives to encourage new development. Situated in the heart of the South Pacific, the Republic of Fiji comprises 333 islands. Sunny, unique and friendly, the Fiji Islands are one thousand miles of pristine white sand beaches, fabulous coral gardens and azure lagoons. Fiji enjoys a tropical maritime climate, without undue extremes of humidity and temperature. The population of Fiji is approximately 832,000 people, most of whom live on the two main islands of Viti Levu and Vanua Levu and comprise a combination of native Fijians (53%), Indians (40%) and a balance of other races. In 1970 Fiji was granted independence and became a self-governing nation within the Commonwealth, after 96 years of British rule. -

Musket-Compendium-2017.Pdf

1 2 Bula and welcome. On behalf of the Musket family we’d like to welcome you to paradise. At Musket Cove you’ll fnd the pace of life smooth and unhurried. Musket is the perfect location to relax and absorb island life. With plenty of space, activities, gourmet dining and over 170 warm and friendly staff here to welcome you to our island home. Vinaka vaka levu. Joe Mar and the team. Contents RESORT AND MARINA MAP 2 ABOUT MUSKET COVE 3 TIPS AND INFORMATION 4 - 9 EAT AND DRINK 10 DIVE INTO PARADISE WITH SUBSURFACE FIJI 11 - 12 ACTIVITIES AND THINGS TO DO 13 MUSKET EXCURIONS AND FISHING 14 MAKARE WELLNESS SPA 15 - 16 MUSKET ACCOMMODATION 17 MUSKET WEDDINGS AND EVENTS 18 A BETTER ENVIRONMENT 19 OUR PETS AND PESTS 20 FIJI LANGUAGE AND CULTURE 21 - 22 EMERGENCY AND SAFETY 23 - 24 SUPPLY OF SERVICES AND OBLIGATIONS 25 1 2 ABOUT MUSKET COVE Malolo Lailai the home of Musket Cove and is located in the Mamanuca group of Islands. You’ll fnd the pace of Island life a little slower than normal, just the way we like it, ensuring all the stresses you came with will be far from your mind by the time you leave. Malolo Lailai is 240 hectares with 10kms of palm fringed beaches and hiking trails. Getting here A leisurely 60 minute cruise from Port Denarau aboard the Malolo Cat, operating 4 dedicated return services daily. Private speedboat charters, seaplane or helicopter transfers can also be arranged. About us The resort is owned and operated by Fiji’s oldest resort company, recently celebrating 40 years’ in the Fijian hospitality industry. -

4348 Fiji Planning Map 1008

177° 00’ 178° 00’ 178° 30’ 179° 00’ 179° 30’ 180° 00’ Cikobia 179° 00’ 178° 30’ Eastern Division Natovutovu 0 10 20 30 Km 16° 00’ Ahau Vetauua 16° 00’ Rotuma 0 25 50 75 100 125 150 175 200 km 16°00’ 12° 30’ 180°00’ Qele Levu Nambouono FIJI 0 25 50 75 100 mi 180°30’ 20 Km Tavewa Drua Drua 0 10 National capital 177°00’ Kia Vitina Nukubasaga Mali Wainingandru Towns and villages Sasa Coral reefs Nasea l Cobia e n Pacific Ocean n Airports and airfields Navidamu Labasa Nailou Rabi a ve y h 16° 30’ o a C Natua r B Yanuc Division boundaries d Yaqaga u a ld Nabiti ka o Macuata Ca ew Kioa g at g Provincial boundaries Votua N in Yakewa Kalou Naravuca Vunindongoloa Loa R p Naselesele Roads u o Nasau Wailevu Drekeniwai Laucala r Yasawairara Datum: WGS 84; Projection: Alber equal area G Bua Bua Savusavu Laucala Denimanu conic: standard meridan, 179°15’ east; standard a Teci Nakawakawa Wailagi Lala w Tamusua parallels, 16°45’ and 18°30’ south. a Yandua Nadivakarua s Ngathaavulu a Nacula Dama Data: VMap0 and Fiji Islands, FMS 16, Lands & Y Wainunu Vanua Levu Korovou CakaudroveTaveuni Survey Dept., Fiji 3rd Edition, 1998. Bay 17° 00’ Nabouwalu 17° 00’ Matayalevu Solevu Northern Division Navakawau Naitaba Ngunu Viwa Nanuku Passage Bligh Water Malima Nanuya Kese Lau Group Balavu Western Division V Nathamaki Kanacea Mualevu a Koro Yacata Wayalevu tu Vanua Balavu Cikobia-i-lau Waya Malake - Nasau N I- r O Tongan Passage Waya Lailai Vita Levu Rakiraki a Kade R Susui T Muna Vaileka C H Kuata Tavua h E Navadra a Makogai Vatu Vara R Sorokoba Ra n Lomaiviti Mago -

Tokoriki Island Resort Mamanuca Islands Status Now Instant Availability on This Property Views Ocean Standard (Grade) 4.5 Palm B.B.Q

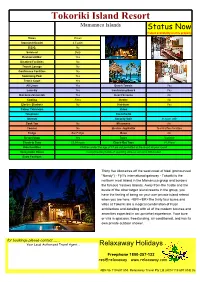

Tokoriki Island Resort Mamanuca Islands Status Now Instant availability on this property Views Ocean Standard (Grade) 4.5 palm B.B.Q. No Serviced Daily Restaurant/Bar Yes Disabled Facilities No Transit Lounge No Conference Facilities No Swimming Pool Yes Tennis Court Yes All Linen Yes Beach Towels Yes Laundry Yes Iron/Ironing Board Yes Balconies/Verandah Yes Insect Screens No Cooling Fans Heater No Electric Blankets No Hairdryer Yes Colour Television Video Telephone Clock/Radio Internet Security Safe In room safe Cook Top No Microwave No Toaster No Electric Jug/Kettle Tea&Coffee Facilities Fridge Bar Fridge Oven No Resort Shop Yes Tours Available Check-In Time 12.00 noon Check-Out Time 10.00am Kids Facilities Children under the age of 12 are not permitted at the resort all year round Honeymoon Bonus Complimentary bottle of sparkling wine on arrival & Gift basket Extra Facilities Thirty five kilometres off the west coast of Nadi (pronounced "Nandy") - Fiji\\'s international gateway - Tokoriki is the northern most island in the Mamanuca group and borders the famous Yasawa Islands. Away from the hustle and the bustle of the other larger island resorts in the group, you have the feeling of being on your own private island retreat when you are here. <BR><BR>The thirty four bures and villas at Tokoriki are a magical combination of Fijian architecture and detailing with all of the modern luxuries and amenities expected in an upmarket experience. Your bure or villa is spacious, freestanding, air conditioned, and has its own private outdoor shower. for bookings please contact…… Your Local Authorised Travel Agent... -

South Sea Island, Infant Meals Are Not Included on Day Cruises Yanuya Monu and Are Payable Direct to the Resort

WHAT TO BRING • Swim wear and towel • Sun hat and lotion Mamanuca Islands • Money for optional purchases • Your camera and a sense of fun! GENERAL INFORMATION & BOOKING CONDITIONS South Sea Vomo • All prices are in Fijian Dollars per person and include taxes where applicable. • Child fares are for children aged between the ages of 5 to 15 inclusive. Infants under 5 travel FOC but must be Tokoriki Sheraton advised at time of booking. With the exception of South Sea Island, infant meals are not included on Day Cruises Yanuya Monu and are payable direct to the resort. Family Pass - 2 adults and up to 3 children. Island Mondriki • Rates include FREE Nadi/Denarau and Coral Coast coach transfers to and from Port Denarau LAUTOKA Matamanoa for most day trips. Please check with your Hotel Tour Desk for departure times. NOTE: The only return coach transfer for the Coral Coast departs the port at 6pm. Beachcomber Treasure • All inclusions are as indicated in the brochure and websites at time of travel. If not stated as included then item/s DAY CRUISES Bounty Island are at guests own cost. Mana South Sea Island • For credit card payments a 2.5% administration fee applies (non refundable). • South Sea Cruises reserves the right to alter prices, apply a fuel surcharge, cancel departures, arrange alternative transport and vary itineraries and services if necessary. All cruises are subject to sea and weather conditions Malamala Island particularly in the interest of passenger safety. Should adverse conditions prevent operation, our liability is limited Likuliku to offering an alternative cruise or appropriate refund no greater than the fare paid. -

Which Fiji Resort Is Perfect for Your Family?

Brought to you by Tourism Fiji Which Fiji resort is perfect for your family? For grown-up families When it comes to family holidays, one size certainly doesn’t fit all. But famously child-friendly Fiji has a resort to suit everyone – from babies to teens and luxury Spending time together as a family of loving grown-up kids, too. So find your perfect island base, start planning then adults? For the ultimate multigenerational pack your bags once travel restrictions are lifted. get-together, the newly launched three- to-six-bedroom residences at Kokomo Private Island (kokomoislandfiji.com) For families with tweens and teens deliver the goods, each with a private pool and direct beach access along with Keeping older kids occupied without a butler (and a nanny if required). The compromising their sense of cool is a A-list luxury of this bolthole in the Kadavu balancing act perfected at Shangri-La’s island chain extends to a spa showcasing Fijian Resort, Yanuca (shangri-la.com), which Fijian beauty and rejuvenation treatments boasts an epic inflatable water park that was and yoga classes on a pontoon moored tailor-made for Survivor: Fiji challenges. This in the lagoon’s tranquil waters. For more Coral Coast favourite was recently given a grown-up indulgence, the remote Yasawa $50 million refurbishment and promises to Island Resort & Spa (yasawa.com) to divert the restless energy of tweens and the far north of the mainland offers teens into mini golf, tennis, basketball and accommodation in just 18 traditionally a host of on-water activities including paddle thatched beachfront bures.