Fieldwork in Theology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exposing Corruption in Progressive Rock: a Semiotic Analysis of Gentle Giant’S the Power and the Glory

University of Kentucky UKnowledge Theses and Dissertations--Music Music 2019 EXPOSING CORRUPTION IN PROGRESSIVE ROCK: A SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF GENTLE GIANT’S THE POWER AND THE GLORY Robert Jacob Sivy University of Kentucky, [email protected] Digital Object Identifier: https://doi.org/10.13023/etd.2019.459 Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Sivy, Robert Jacob, "EXPOSING CORRUPTION IN PROGRESSIVE ROCK: A SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF GENTLE GIANT’S THE POWER AND THE GLORY" (2019). Theses and Dissertations--Music. 149. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/music_etds/149 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations--Music by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STUDENT AGREEMENT: I represent that my thesis or dissertation and abstract are my original work. Proper attribution has been given to all outside sources. I understand that I am solely responsible for obtaining any needed copyright permissions. I have obtained needed written permission statement(s) from the owner(s) of each third-party copyrighted matter to be included in my work, allowing electronic distribution (if such use is not permitted by the fair use doctrine) which will be submitted to UKnowledge as Additional File. I hereby grant to The University of Kentucky and its agents the irrevocable, non-exclusive, and royalty-free license to archive and make accessible my work in whole or in part in all forms of media, now or hereafter known. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with James Poyser

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with James Poyser Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Poyser, James, 1967- Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with James Poyser, Dates: May 6, 2014 Bulk Dates: 2014 Physical 7 uncompressed MOV digital video files (3:06:29). Description: Abstract: Songwriter, producer, and musician James Poyser (1967 - ) was co-founder of the Axis Music Group and founding member of the musical collective Soulquarians. He was a Grammy award- winning songwriter, musician and multi-platinum producer. Poyser was also a regular member of The Roots, and joined them as the houseband for NBC's The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon. Poyser was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on May 6, 2014, in New York, New York. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2014_143 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® Songwriter, producer and musician James Jason Poyser was born in Sheffield, England in 1967 to Jamaican parents Reverend Felix and Lilith Poyser. Poyser’s family moved to West Philadelphia, Pennsylvania when he was nine years old and he discovered his musical talents in the church. Poyser attended Philadelphia Public Schools and graduated from Temple University with his B.S. degree in finance. Upon graduation, Poyser apprenticed with the songwriting/producing duo Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff. Poyser then established the Axis Music Group with his partners, Vikter Duplaix and Chauncey Childs. He became a founding member of the musical collective Soulquarians and went on to write and produce songs for various legendary and award-winning artists including Erykah Badu, Mariah Carey, John Legend, Lauryn Hill, Common, Anthony Hamilton, D'Angelo, The Roots, and Keyshia Cole. -

Neuhoff, Laura-Brynn.Pdf (929Kb)

“THE BIGGEST COLORED SHOW ON EARTH”: HOW MINSTRELSY HAS DEFINED PERFORMANCES OF AFRICAN AMERICAN IDENTITY FROM 19TH CENTURY THEATER TO HIP HOP A Senior Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in American Studies By Laura-Brynn Neuhoff Washington, D.C. April 26, 2017 “THE BIGGEST COLORED SHOW ONE EARTH”: HOW MINSTRELSY HAS DEFINED PERFORMANCES OF AFRICAN AMERICAN IDENTITY FROM 19TH CENTURY THEATER TO HIP HOP Laura-Brynn Neuhoff Thesis Adviser: Marcia Chatelain, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This senior thesis seeks to answer the following question: how and why is the word “minstrel” and associated images still used in American rap and hip hop performances? The question was sparked by the title of a 2005 rap album by the group Little Brother: The Minstrel Show. The record is packaged as a television variety show, complete with characters, skits, and references to blackface. This album premiered in the heat of the Minstrel Show Debate when questions of authenticity and representation in rap and hip hop engaged community members. My research is first historical: I analyze images of minstrelsy and reviews of minstrel shows from the 1840s into the twentieth century to understand how the racist images persisted and to unpack the ambiguity of the legacy of black blackface performers. I then analyze the rap scene from the late 2000-2005, when the genre most poignantly faced the identity crisis spurred by those referred to as “minstrel” performers. Having conducted interviews with the two lyricists of Little Brother: Rapper Big Pooh and Phonte, I primarily use Little Brother as my center of research, analyzing their production in conjunction with their spatial position in the hip hop community. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE IDS Proudly Announces Questlove To

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE IDS Proudly Announces Questlove to Saturday Speaker Lineup Caption Drummer, DJ, producer, culinary entrepreneur, New York Times best-selling author, and co-founder of The Roots - Questlove – will join IDS19 as a keynote speaker Toronto, Canada – December 6, 2018 – On Saturday, January 19, 2019, Interior Design Show 2019 (IDS19) will welcome creative chameleon, Questlove, to the Caesarstone Stage to Questlove speak to IDS19 attendees from 11:00 a.m. – 12:00 p.m. EST. Questlove will speak in conversation with Adam Sandow, CEO of SANDOW, and partner in Questlove’s new venture, CREATIVE HOUSE. Launching in 2019, CREATIVE HOUSE will unite a diverse mix of artists, designers, and inventors to inspire, connect, bringing new and inspired brands and product to market. This new venture will use a plurality of means to engage innovative solutions and gather inspiring individuals from across platforms such as printed publications, fireside chats, conferences and an agency for product development. Experiential and transformative, IDS19 brings together compelling concepts, innovative products, upcoming talent and key experts in the industry so the best of the future can inspire guests. Questlove’s commitment to creativity and diverse background will present a dynamic and forward-thinking view of how creativity can extend through many disciplines and inspire design. Questlove will be onsite after his talk for a special book signing of his New York Times bestseller Creative Quest. Questlove is the Musical Director for The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon, where his beloved Roots crew serves as the house band. Beyond that, this 5-time GRAMMY Award-winning musician’s indisputable reputation has landed him musical directing positions with everyone from D’Angelo to Eminem to Jay-Z. -

00:00:00 Music Transition “Crown Ones” Off the Album Stepfather by People Under the Stairs

00:00:00 Music Transition “Crown Ones” off the album Stepfather by People Under The Stairs 00:00:06 Oliver Wang Host Hello, I’m Oliver Wang. 00:00:08 Morgan Host And I’m Morgan Rhodes. You’re listening to Heat Rocks. Rhodes 00:00:10 Oliver Host Morgan and I wanted to kick off 2020, and the 2020s in general, with a look back at the decade we just left behind, and to do so the two of us have compiled our favorite ten of the 2010s. 00:00:24 Music Music [The following songs play in rapid succession, crossfading into each other with no gap between them] “Fall in Love (Your Funeral)” off the album New Amerykah Part Two (Return of the Ankh) by Erykah Badu. Up-tempo, grooving R&B/soul. You don't wanna fall in love [Fades into…] 00:00:28 Music Music “See You Again” off the album Flower Boy by Tyler, the Creator. A short instrumental section with soaring horns. Fades into… 00:00:35 Music Music “Ah Yeah” off the album Black Radio by Robert Glasper Experiment. Slow, harmonized vocalizing over snaps. Fades into… 00:00:44 Music Music “Momma” off the album To Pimp a Butterfly by Kendrick Lamar. Mid-tempo rap. Sun beaming on his beady beads exhausted Tossing footballs with his ashy black ankles [Fades into…] 00:00:50 Music Music “Drunk in Love” off the album Beyoncé by Beyoncé. Poppy hip-hop. Surfboard, surfboard Graining on that wood, graining, graining on that wood [Fades into…] 00:00:56 Music Music “Nights” off the album Blond by Frank Ocean. -

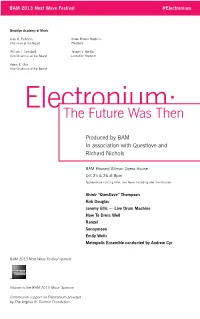

Electronium:The Future Was Then

BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival #Electronium Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Karen Brooks Hopkins, Chairman of the Board President William I. Campbell, Joseph V. Melillo, Vice Chairman of the Board Executive Producer Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board Electronium:The Future Was Then Produced by BAM In association with Questlove and Richard Nichols BAM Howard Gilman Opera House Oct 25 & 26 at 8pm Approximate running time: two hours including one intermission Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson Kirk Douglas Jeremy Ellis — Live Drum Machine How To Dress Well Rahzel Sonnymoon Emily Wells Metropolis Ensemble conducted by Andrew Cyr BAM 2013 Next Wave Festival sponsor Viacom is the BAM 2013 Music Sponsor Commission support for Electronium provided by The Virginia B. Toulmin Foundation Electronium Metropolis Ensemble conducted by Andrew Cyr: Kristin Lee, violin (concertmaster) Francisco Fullana, violin Karen Kim, viola Hiro Matsuo, cello Mellissa Hughes, soprano Virginia Warnken, alto Geoffrey Silver, tenor Jonathan Woody, bass-baritone ADDITIONAL PRODUCTION CREDITS Arrangements by Daniel Felsenfeld, DD Jackson, Patrick McMinn and Anthony Tid Lighting design by Albin Sardzinski Sound engineering by John Smeltz Stage design by Alex Delaunay Stage manager Cheng-Yu Wei Electronium references the first electronic synthesizer created exclusively for the composition and performance of music. Initially created for Motown by composer-technologist Raymond Scott, the electronium was designed but never released for distribution; the one remaining machine is undergoing restoration. Complemented by interactive lighting and aural mash-ups, the music of Electronium: The Future Was Then honors the legacy of the electronium in a production that celebrates both digital and live music interplay. -

Cultural and Musical Implications of Live-Instrumental Hip-Hop" (2016)

University of Vermont ScholarWorks @ UVM UVM College of Arts and Sciences College Honors Theses Undergraduate Theses 2016 From The Ground Up: Cultural and Musical Implications of Live- Instrumental Hip-Hop Jonah Ullman Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/castheses Recommended Citation Ullman, Jonah, "From The Ground Up: Cultural and Musical Implications of Live-Instrumental Hip-Hop" (2016). UVM College of Arts and Sciences College Honors Theses. 28. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/castheses/28 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at ScholarWorks @ UVM. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM College of Arts and Sciences College Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ UVM. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From The Ground Up: Cultural and Musical Implications of LiveInstrumental HipHop A thesis submitted by Jonah Ullman In fulfillment of the requirements for College Honors UNIVERSITY OF VERMONT College of Arts and Sciences May, 2016 ADVISER: Alex Stewart ii ABSTRACT Traditional live instruments have played an important role in hiphop production in various capacities since the earliest stages of the genre’s development. The dominant historical narrative often omits the frequency with which live instruments have been used in hiphop. The authenticity of their use has been a point of contention in the discourse of hiphop producers, consumers, critics and scholars. When used in accordance with hiphop’s aesthetic sensibilities, however, they become a vehicle for innovative and authentic hiphop. Tasteful use of live instruments opens up a range of possibilities in the realms of arrangement techniques and compositional freedom. -

Cultural Remix: Polish Hip-Hop and the Sampling of Heritage by Alena

Cultural Remix: Polish Hip-Hop and the Sampling of Heritage by Alena Gray Aniskiewicz A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Slavic Languages and Literatures) in the University of Michigan 2019 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Benjamin Paloff, Chair Associate Professor Herbert J. Eagle Professor Charles Hiroshi Garrett Visiting Assistant Professor Jodi C. Greig, University of Wisconsin-Madison Alena Gray Aniskiewicz [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0002-1922-291X © Alena Gray Aniskiewicz 2019 To my parents, for everything. (Except hip-hop. For that, thank you, DH.) ii Acknowledgements To Herb Eagle, whose comments and support over the years have been invaluable. To Jodi Greig, whose reputation preceded her, but didn’t do her justice as a friend or scholar. To Charles Hiroshi Garrett, who was my introduction to musicology fourteen years ago and has been a generous reader and advisor ever since. And to Benjamin Paloff, who gave me the space to figure out what I wanted and then was there to help me figure out how to get it. I couldn’t have asked for a better committee. To my peers, who became friends along the way. To my friends, who indulged all the Poland talk. To Culture.pl, who gave me a community in Warsaw and kept Poland fun. To the Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures, the Copernicus Program in Polish Studies, the Rackham Graduate School, and the Sweetland Writing Center, whose generous funding made this dissertation possible. I’m thankful to have had you all in my corner. -

FY19 Annual Report

STAFF LISTING Lindsey Forden, Director of Development | [email protected] 609.258.6544 Brannan Osburn Berman, Director of Individual Giving | [email protected] 609.258.6548 Gail Campanella, Development Operations Manager | [email protected] 609.258.9654 Dana Lopatin, Donor Benefits Associate | [email protected] 609.258.6543 Kelsey Mulholland, Development Associate, Institutional Giving | [email protected] 609.258.4646 PHOTO CREDITS CONTACT US Inside Front Cover (l-r) Greg Wood and Mahira Kakkar in Skylight, Photo credit: T. McCarter Theatre Center Charles Erickson; P.2 Managing Director Michael S. Rosenberg, Photo credit: Matt 91 University Place Pilsner; P.2 Artistic Director and Resident Playwright Emily Mann, Photo credit: Matt Princeton, NJ 08540 Pilsner; P.2 Presented Series Director Bill Lockwood, Photo credit: Matt Pilsner; P.3 (l-r) 609.258.6544 Sierra Boggess and Andrew Veenstra in The Age of Innocence, Photo credit: T. Charles [email protected] Erickson; P.4 (l-r) The cast of The Age of Innocence, Photo credit: T. Charles Erickson; P.4 (l-r) Johnny Ramey & Will Cobbs in Detroit '67, Photo credit: T. Charles Erickson; P.4 (l-r) Jordan Boatman & Lisa Banes in The Niceties, Photo credit: T. Charles Erickson; P.5 (l-r) The ensemble of A Christmas Carol, Photo credit: T. Charles Erickson; P.5 (l-r) STAY CONNECTED Brad Oscar and Shay Vawn in The Gods of Comedy, Photo credit: T. Charles Erickson; mccarter.org P.5 Mahira Kakkar in Skylight, Photo credit: T Charles Erickson; P.6 Momix, Photo credit: Courtesy -

Black Messiah" IDAG!

2014-12-15 09:30 CET D'Angelo släpper nya albumet "Black Messiah" IDAG! The wait is finally over! D’Angelo and The Vanguard’s highly anticipated and much buzzed about brand new album, Black Messiah, is available today (12/15/14) at digital and retail music providers. The studio recorded version of “Really Love” from Black Messiah, will be serviced to radio today. Nearly 15 years in the making, Black Messiah contains 12 tracks of timeless music with poignant and provocative lyrics that requires repeat listening at maximum volume! On the album, D’Angelo is joined by his band, The Vanguard, alongside Pino Palladino, James Gadson and Questlove on various tracks on the album. All lyrics were written by D’Angelo in addition to Q-Tip and Kendra Foster who both wrote lyrics on several songs. With the high quality of live musicianship featured on the album, it’s important to note that “No digital ‘plug-ins’ of any kind were used in this recording. All of the recording, processing, effects and mixing was done in the analog domain using tape and mostly vintage equipment.” D’Angelo had this to say about Black Messiah in the album’s forward: "‘Black Messiah’ is a hell of a name for an album. It can be easily misunderstood. Many will think it’s about religion. Some will jump to the conclusion that I'm calling myself a Black Messiah. For me the title is about all of us. It's about the world. It's about an idea we can all aspire to. -

Merrimack College at the Intersection of Rock and Rap Analyzing The

Merrimack College At the Intersection of Rock and Rap Analyzing the History of Fusions Dillon Cloonan Senior Capstone for Music Major Dr. Laura Pruett May 15, 2020 1 The start of a brand-new decade never fails to feel refreshing. It is a time to reflect on the ups and downs of the past ten years, and mentally wipe the slate clean as the fresh decade approaches. Preparing for what the future will bring is an exciting thought, and what will come next is inevitably unpredictable. The same is absolutely true for music. A decade is a fantastic lens for examining the changes in popular, live and underground music. Every single decade since the 1920’s has brought forth new changes in style, instrumentation, performance and delivery. Some of the most notable of these changes include the emergence of jazz in the 1920’s, the popularization of Big Band in the 40’s, the British invasion in the 60’s, the fight for the legitimacy of rap in the 80’s, and the domination of synths and computer music beginning in the 2000’s among dozens of other examples. However, the most interesting example throughout decades to analyze that was not mentioned is the fusion of rap and rock styles of music in the popular eye beginning in the mid 80’s and 90’s. The alliance of these two styles of music impacted our current landscape for music more dramatically than any other combination. The importance of this specific fusion stretches from the general public’s acceptance of hip-hop itself, and the gateway for other styles of music to be blended with rap, such as country, metal, jazz, and electronic music among others. -

Ahmir “Questlove”

Questlove Drummer, DJ, producer, culinary entrepreneur, New York Times best-selling author, and member of The Roots - Questlove, is the unmistakable heartbeat of Philadelphia’s most influential hip-hop group. He is the Musical Director for The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon, where his beloved Roots crew serves as house band. Beyond that, this 4-time GRAMMY Award winning musician's indisputable reputation has landed him musical directing positions with everyone from D'Angelo to Eminem to Jay-Z. Questlove has also released two books including the New York Times Bestseller Mo’ Meta Blues and Soul Train: The Music, Dance and Style of a Generation. One of this latest endeavors includes scoring Chris Rock’s new film, Top Five, and also working as the music supervisor. Questlove is the Executive Producer of VH1’s Soundclash, hosted by Diplo and Executive Producer of VH1’s Philly 4th of July Jam. Questlove made his way into the culinary world with his signature "Love's Drumstick.” Currently, Questlove is hosting a series of Food Salons with world-renowned and innovative chefs at his Financial District apartment in the NY by Gehry building. Questlove has appeared as a Guest Judge on Top Chef Season 11, his food and culinary endeavors have been featured on the cover of New York Magazine, in Food & Wine Magazine, Bon Appetit, and seen on The View, Watch What Happens Live, and Late Night with Jimmy Fallon. He is a Celebrity Ambassador for The Food Bank NYC, is on the City Harvest Food Council, a board member of Edible Schoolyard, and the first Artist-in-Residence at the Made in NY Media Center.