Neuhoff, Laura-Brynn.Pdf (929Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cowl Island/Page 19 Vol

BACK PAGE: Focus on student health Deanna Cioppa '07 Men's hoops win Think twice before going tanning for spring Are you getting enough sleep? Experts say reviews Trinity over West Virginia, break ... and get a free Dermascan in Ray extra naps could save your heart Hear Repertory Theater's bring Friars back Cafeteria this coming week/Page 4 from the PC health center/Page 8 latest, A Delicate into the running for Balance/Page 15 NCAA bid Est. 1935 Sarah Amini '07 Men's and reminisces about women’s track win riding the RIPTA big at Big East 'round Rhose Championships The Cowl Island/Page 19 Vol. LXXI No. 18 www.TheCowl.com • Providence College • Providence, R.I. February 22, 2007 Protesters refuse to be silenced by Jennifer Jarvis ’07 News Editor s the mild weather cooled off at sunset yesterday, more than 100 students with red shirts and bal loons gathered at the front gates Aof Providence College, armed with signs saying “We will not stop fighting for an end to sexual assault,” and “Vaginas are not vulgar, rape is vulgar.” For the second year in a row, PC students protested the decision of Rev. Brian J. Shanley, O.P., president of Providence College, to ban the production of The Vagina Monologues on 'campus. Many who saw a similar protest one year ago are asking, is this deja vu? Perhaps, but the cast and crew of The Vagina Monologues and many other sup porters said they will not stop protesting just because the production was banned last year. -

Williams, Hipness, Hybridity, and Neo-Bohemian Hip-Hop

HIPNESS, HYBRIDITY, AND “NEO-BOHEMIAN” HIP-HOP: RETHINKING EXISTENCE IN THE AFRICAN DIASPORA A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Maxwell Lewis Williams August 2020 © 2020 Maxwell Lewis Williams HIPNESS, HYBRIDITY, AND “NEO-BOHEMIAN” HIP-HOP: RETHINKING EXISTENCE IN THE AFRICAN DIASPORA Maxwell Lewis Williams Cornell University 2020 This dissertation theorizes a contemporary hip-hop genre that I call “neo-bohemian,” typified by rapper Kendrick Lamar and his collective, Black Hippy. I argue that, by reclaiming the origins of hipness as a set of hybridizing Black cultural responses to the experience of modernity, neo- bohemian rappers imagine and live out liberating ways of being beyond the West’s objectification and dehumanization of Blackness. In turn, I situate neo-bohemian hip-hop within a history of Black musical expression in the United States, Senegal, Mali, and South Africa to locate an “aesthetics of existence” in the African diaspora. By centering this aesthetics as a unifying component of these musical practices, I challenge top-down models of essential diasporic interconnection. Instead, I present diaspora as emerging primarily through comparable responses to experiences of paradigmatic racial violence, through which to imagine radical alternatives to our anti-Black global society. Overall, by rethinking the heuristic value of hipness as a musical and lived Black aesthetic, the project develops an innovative method for connecting the aesthetic and the social in music studies and Black studies, while offering original historical and musicological insights into Black metaphysics and studies of the African diaspora. -

Corporate Registry Registrar's Periodical Template

Service Alberta ____________________ Corporate Registry ____________________ Registrar’s Periodical SERVICE ALBERTA Corporate Registrations, Incorporations, and Continuations (Business Corporations Act, Cemetery Companies Act, Companies Act, Cooperatives Act, Credit Union Act, Loan and Trust Corporations Act, Religious Societies’ Land Act, Rural Utilities Act, Societies Act, Partnership Act) 101225945 SASKATCHEWAN LTD. Other 10978477 CANADA LTD. Federal Corporation Prov/Territory Corps Registered 2018 SEP 06 Registered Registered 2018 SEP 06 Registered Address: 2865 Address: 5009 - 47 STREET PO BOX 20 STN MAIN MADLE WAY NORTH WEST, EDMONTON (27419-1 TRK), LLOYDMINSTER ALBERTA, T6T 0W8. No: 2121414144. SASKATCHEWAN, S9V 0X9. No: 2121414847. 1133703 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps 101259911 SASKATCHEWAN LTD. Other Registered 2018 SEP 05 Registered Address: 103, 201-2 Prov/Territory Corps Registered 2018 SEP 11 Registered STREET NE, SLAVE LAKE ALBERTA, T0G2A2. No: Address: 3315 11TH AVE NW, EDMONTON 2121411470. ALBERTA, T6T 2C5. No: 2121423640. 1178223 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps 101289693 SASKATCHEWAN LTD. Other Registered 2018 SEP 04 Registered Address: 114-35 Prov/Territory Corps Registered 2018 SEP 04 Registered INGLEWOOD PARK SE, CALGARY ALBERTA, Address: 410, 316 WINDERMERE ROAD NW, T2G1B5. No: 2121411033. EDMONTON ALBERTA, T6W 2Z8. No: 2121411199. 1178402 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps 102058691 SASKATCHEWAN LTD. Other Registered 2018 SEP 06 Registered Address: 1101-3961 Prov/Territory Corps Registered 2018 SEP 06 Registered 52ND AVENUE NE, CALGARY ALBERTA, T3J0J7. Address: 5016 LAC STE. ANNE TRAIL SOUTH PO No: 2121414698. BOX 885, ONOWAY ALBERTA, T0E 1V0. No: 2121414276. 1179276 B.C. LTD. Other Prov/Territory Corps Registered 2018 SEP 13 Registered Address: SUITE 102059279 SASKATCHEWAN LTD. -

Aster Marketing Thesi

ERASMUS SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS ECONOMICS - MARKETING MASTER THESIS It's All in the Lyrics: The Predictive Power of Lyrics Date : August, 2014 Name : Maarten de Vos Student ID : 331082 Supervisor : Dr. F. Deutzmann Abstract: This research focuses on whether it is possible to determine popularity of a specific song based on its lyrics. The songs which were considered were in the US Billboard Top 40 Singles Chart between 2006 and 2011. From this point forward, k-means clustering in RapidMiner has been used to determine the content that was present in the songs. Furthermore, data from Last.FM was used to determine the popularity of a song. This resulted in the conclusion that up to a certain extent, it is possible to determine popularity of songs. This is mostly applicable to the love theme, but only in the specific niches of it. Keywords: Content analysis, RapidMiner, Lyric analysis, Last.FM, K-means clustering, US Billboard Top 40 Singles Chart, Popularity 1 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Motivation ........................................................................................................................................ 5 2.1. Academic contribution .............................................................................................................. 5 2.2. Managerial contribution .......................................................................................................... -

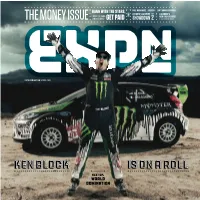

KEN BLOCK Is on a Roll Is on a Roll Ken Block

PAUL RODRIGUEZ / FRENDS / LYN-Z ADAMS HAWKINS HANG WITH THE STARS, PART lus OLYMPIC HALFPIPE A SLEDDER’S (TRAVIS PASTRANA, P NEW ENERGY DRINK THE MONEY ISSUE JAMES STEWART) GET PAID SHOWDOWN 2 IT’S A SHOCKER! PAGE 8 ESPN.COM/ACTION SPRING 2010 KENKEN BLOCKBLOCK IS ON A RROLLoll NEXT UP: WORLD DOMINATION SPRING 2010 X SPOT 14 THE FAST LIFE 30 PAY? CHECK. Ken Block revolutionized the sneaker Don’t have the board skills to pay the 6 MAJOR GRIND game. Is the DC Shoes exec-turned- bills? You can make an action living Clint Walker and Pat Duffy race car driver about to take over the anyway, like these four tradesmen. rally world, too? 8 ENERGIZE ME BY ALYSSA ROENIGK 34 3BR, 2BA, SHREDDABLE POOL Garth Kaufman Yes, foreclosed properties are bad for NOW ON ESPN.COM/ACTION 9 FLIP THE SCRIPT 20 MOVE AND SHAKE the neighborhood. But they’re rare gems SPRING GEAR GUIDE Brady Dollarhide Big air meets big business! These for resourceful BMXer Dean Dickinson. ’Tis the season for bikinis, boards and bikes. action stars have side hustles that BY CARMEN RENEE THOMPSON 10 FOR LOVE OR THE GAME Elena Hight, Greg Bretz and Louie Vito are about to blow. FMX GOES GLOBAL 36 ON THE FLY: DARIA WERBOWY Freestyle moto was born in the U.S., but riders now want to rule MAKE-OUT LIST 26 HIGHER LEARNING The supermodel shreds deep powder, the world. Harley Clifford and Freeskier Grete Eliassen hits the books hangs with Shaun White and mentors Lyn-Z Adams Hawkins BOBBY BROWN’S BIG BREAK as hard as she charges on the slopes. -

The Life & Rhymes of Jay-Z, an Historical Biography

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 Omékongo Dibinga, Doctor of Philosophy, 2015 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Barbara Finkelstein, Professor Emerita, University of Maryland College of Education. Department of Teaching and Learning, Policy and Leadership. The purpose of this dissertation is to explore the life and ideas of Jay-Z. It is an effort to illuminate the ways in which he managed the vicissitudes of life as they were inscribed in the political, economic cultural, social contexts and message systems of the worlds which he inhabited: the social ideas of class struggle, the fact of black youth disempowerment, educational disenfranchisement, entrepreneurial possibility, and the struggle of families to buffer their children from the horrors of life on the streets. Jay-Z was born into a society in flux in 1969. By the time Jay-Z reached his 20s, he saw the art form he came to love at the age of 9—hip hop— become a vehicle for upward mobility and the acquisition of great wealth through the sale of multiplatinum albums, massive record deal signings, and the omnipresence of hip-hop culture on radio and television. In short, Jay-Z lived at a time where, if he could survive his turbulent environment, he could take advantage of new terrains of possibility. This dissertation seeks to shed light on the life and development of Jay-Z during a time of great challenge and change in America and beyond. THE LIFE & RHYMES OF JAY-Z, AN HISTORICAL BIOGRAPHY: 1969-2004 An historical biography: 1969-2004 by Omékongo Dibinga Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Maryland, College Park, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2015 Advisory Committee: Professor Barbara Finkelstein, Chair Professor Steve Klees Professor Robert Croninger Professor Derrick Alridge Professor Hoda Mahmoudi © Copyright by Omékongo Dibinga 2015 Acknowledgments I would first like to thank God for making life possible and bringing me to this point in my life. -

Karaoke Songs by Title

Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #9 Dream Lennon, John 1985 Bowling For Soup (Day Oh) The Banana Belefonte, Harry 1994 Aldean, Jason Boat Song 1999 Prince (I Would Do) Anything Meat Loaf 19th Nervous Rolling Stones, The For Love Breakdown (Kissed You) Gloriana 2 Become 1 Jewel Goodnight 2 Become 1 Spice Girls (Meet) The Flintstones B52's, The 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The (Reach Up For The) Duran Duran 2 Faced Louise Sunrise 2 For The Show Trooper (Sitting On The) Dock Redding, Otis 2 Hearts Minogue, Kylie Of The Bay 2 In The Morning New Kids On The (There's Gotta Be) Orrico, Stacie Block More To Life 2 Step Dj Unk (Your Love Has Lifted Shelton, Ricky Van Me) Higher And 20 Good Reasons Thirsty Merc Higher 2001 Space Odyssey Presley, Elvis 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 21 Questions 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay-Z & Beyonce 24 Jem (M-F Mix) 24 7 Edmonds, Kevon 1 Thing Amerie 24 Hours At A Time Tucker, Marshall, 1, 2, 3, 4 (I Love You) Plain White T's Band 1,000 Faces Montana, Randy 24's Richgirl & Bun B 10,000 Promises Backstreet Boys 25 Miles Starr, Edwin 100 Years Five For Fighting 25 Or 6 To 4 Chicago 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 26 Cents Wilkinsons, The 10th Ave Freeze Out Springsteen, Bruce 26 Miles Four Preps, The 123 Estefan, Gloria 3 Spears, Britney 1-2-3 Berry, Len 3 Dressed Up As A 9 Trooper 1-2-3 Estefan, Gloria 3 Libras Perfect Circle, A 1234 Feist 300 Am Matchbox 20 1251 Strokes, The 37 Stitches Drowning Pool 13 Is Uninvited Morissette, Alanis 4 Minutes Avant 15 Minutes Atkins, Rodney 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin 15 Minutes Of Shame Cook, Kristy Lee Timberlake 16 @ War Karina 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake & 16th Avenue Dalton, Lacy J. -

Blige Back On

a pan 31 o The most popular singles andt-acks. acc Jrding to R &B Hp Hop radio aL 1iemeimpressions meas.Ired by Nielsen Broadcast Data Systems and sales data from subset Are FMB/Hip-Hop stras compiled by Nielsen Sourdscan Greates GsnerSales and Greatest Gainer; Airplay are awarded respectively for the largest retail sales and arptEy ricreases or the chart. See 3ha is Legend br r Iles and explanations. r 2007, VNU Business Media. Inc and Nielsen SoundScan. Inc. All rights est Ned ARRA" MONRONEI l' SALES DATA COMPILED BY Nielsen Nielsen aroactsst r-a J SOUn4SCHn 3- E TITLE Artist ER) PRODUCER (SONGWRITER) IMPRINT / PROMOTION en it Elisabeth Withers IRREPLACEABLE B BE WITH YOU 1 1 1 T.GAD (T e BLUE NOTE VIRGIN ir Sw1CAIE.BIVCMFSJE -0 (S9STHJI gALES1LS13iKíBi.TEi6wMAGEKE1 CAEMORNIDRPEFFZ) Oi GAD.E.WITHERS) Clara ®LISTEN Beyonce PROMISE 2 2 2 THE UNDERDOGS B KNOWLES IB KNOWLES.H. KRIEGERS CUILER,A PREVER) Co MUSIC WORLD COLUMBIA P0L0W DA DON (C. PHARRIS.J CAMERON.J JONES E. WILLIAMS) 00 LAFACE ZOMBA er Jay -Z YOU Lloyd Featuring Lil' Wayne ki 30 SOMETHING ROC JAMIDJMG a DR. EIRE C CARTED : - D PARKER) -A- FELLADEF 3 BIG REESE. JASPER (M SINCLAIR,J CAMERON. D CARTER.9 KEMP) 0 THE INC /UNIVERSAL MOTOWN IS ' 0 available only ME WHAT YOU GOT Jay -Z ! 3 I WANNA LOVE YOU Akon Featuring Snoop Dogg SHOW 4 4 3 JUST BLAZE (SC CARTE LER.0 RIDENHOUR.J BOXLEVM.MCEWAN) 0 ROC -A- FELLADEF JAMIDJMG A THIAM E AM,C BROADUSI Q KONVICT %UPFRONT /SRC,UNIVERSAL MOTOWN on 12 -inch Gerald Levert WE FLY HIGH Jim Jones IN MY SONGS 6C 5 G.LEVERT,E NICHOLAS (G LEVERT.E LEVERT,SR.,E t NICHOLAS) ATLANTII' Z. -

WXYC Brings You Gems from the Treasure of UNC's Southern

IN/AUDIBLE LETTER FROM THE EDITOR a publication of N/AUDIBLE is the irregular newsletter of WXYC – your favorite Chapel Hill radio WXYC 89.3 FM station that broadcasts 24 hours a day, seven days a week out of the Student Union on the UNC campus. The last time this publication came out in 2002, WXYC was CB 5210 Carolina Union Icelebrating its 25th year of existence as the student-run radio station at the University of Chapel Hill, NC 27599 North Carolina at Chapel Hill. This year we celebrate another big event – our tenth anni- USA versary as the first radio station in the world to simulcast our signal over the Internet. As we celebrate this exciting event and reflect on the ingenuity of a few gifted people who took (919) 962-7768 local radio to the next level and beyond Chapel Hill, we can wonder request line: (919) 962-8989 if the future of radio is no longer in the stereo of our living rooms but on the World Wide Web. http://www.wxyc.org As always, new technology brings change that is both exciting [email protected] and scary. Local radio stations and the dedicated DJs and staffs who operate them are an integral part of vibrant local music communities, like the one we are lucky to have here in the Chapel Hill-Carrboro Staff NICOLE BOGAS area. With the proliferation of music services like XM satellite radio Editor-in-Chief and Live-365 Internet radio servers, it sometimes seems like the future EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Nicole Bogas of local radio is doomed. -

1/08 Jan|Feb

# 1/08 JAN|FEB KAPU ZINE EDITORIAL Salut! Ich spar mir an dieser Stelle den obligatorischen Jahresrückblick! Straight forward lautet die Devise und ich persönlich freu mich auf das kommende Jahr. Programmatisch starten wir mit einer, meiner Meinung nach, durchaus gelungenen Mischung. Neben einigen internationalen Acts, auf die ihr euch schon freuen könnt, kommen auch österreichische und vor allem Linzer MusikerInnen nicht zu kurz, die mindestens die gleiche Aufmerksamkeit verdienen. Zum ersten mal wird Ende Fe- bruar das O-Heim-Mini-Winter-Festival stattfinden. Stationen sind die STWST und die KAPU, die sich neben dem Verein „Open Air Ottensheim“ fürs Programm ver- antwortlich zeigen. Aber das Programm könnt ihr auf den folgenden Seiten ja in aller Ruhe nachlesen. Was passiert ansonsten in der neuen KAPU-Saison? Jahreswechsel ziehen ja meist große Vorsätze und Pläne mit sich. Das ist bei uns nicht anders. Ein Bisschen sei schon mal verraten... Wir sind wie immer voller Wahnsinnsideen und Tatendrang! Für den Jahresanfang stehen zwei Projekte an. Einerseits wird die KAPUtique ihr virtuelles Dahinsiechen endgültig hinter sich lassen und in neuem Glanze im ehemaligen Fiftitu%-Büro im 1. Stock auferstehen. Das Ganze wird natürlich gebührend gefeiert; doch mehr dazu weiter hinten. Ebenfalls geplant ist eine „offene KünstlerInnenwerkstätte“; einen genauen Zeitplan dafür gibt es leider bis zum jetzigen Zeitpunkt noch nicht. Doch was nicht ist, das kann noch werden. Gebt uns noch ein wenig Zeit und dann werdet ihr auch über Details und Nutzungsmöglichkeiten umgehend informiert (KAPUzine LeseInnen sind ja immer vorn dabei! Auch wenn es diesmal etwas später kommt, doch auch DruckerInnen verdienen Feier- tagsurlaub.) Ebenfalls in Planung ist ein neuer KAPU-Sampler; die ersten Bands sind angeheuert, die Diskussion um den Titel ist nach kämpferischen Aus- einandersetzungen abgeschlossen und wir sind gespannt, wer aller seinen/Ihren Weg auf diese kleine silberne Scheibe findet. -

To Elektra EKL-264 Mono / EKS-7264 Stereo "The BLUES Project"

DAVE RAY: Dave "Snaker" Ray, whose ambition is to be a doctor, started playing guitar while a sophomore in high school. He origin ally began with blues (Leadbelly) to keep his fingers nimble fo r what he thought would be a classical-flamenco guitarist career. "After an adagio by Sor and a hacked-up Farruca, I began playing Led better's stuff exclusively, " Dave reports. He began playing the 12-string guitar when a senior in high school, and lists as early influences, Elvis' Sun label recordings, Bo Diddley, Muddy Waters, early Chicago, and, of course, Leadbelly. " I sing the blues because it's a medium not as demanding as literatu re or serious music, and free enough to permit a total statement of personality and. self, " Dave states. "I play blues because 1 feel it's important to me to express myself and because I feel it's a significant form of music which hasn't had enough dispersement. As far as white men playing blues, that's all who do play blues. the new Negroes are too busy (doing other things). " Discography: Blues, Rags and Hollers (Elektra EKL 240). Dave Ray may soon be heard, with John Koerner and Tony Glover, on Elektra EKL 267. ERIC VON SCHMIDT: E ric w rites: "B orn 1931; began singing in 1948; first influences were Leadbelly, Josh White and Jelly Roll Morton — then Library of Congress material and field recordings. Worked as magazine illustrator, then painter until 1952... two years in the army, and then to Florida, where I worked as a frame-maker and built a 27-foot ketch which was almost called the 'John Hurt'. -

P22 Layout 1

22 Established 1961 Tuesday, June 4, 2019 Lifestyle Gossip he Strokes and Charli XCX’s Governors Ball with the likes of SOB X RBE and Soccer Mommy - wasn’t fans affected by the cancellation, which means customers T sets were cancelled due to thunderstorms. The able to play. However, the 26-year-old star treated her with Sunday day tickets will get all their money back, severe weather forecast meant the final day of fans to a last minute performance at Le Poisson Rouge, while those with a three-day weekend pass will likely get a the festival in New York was postponed until and the intimate club show immediately sold out after the third back. In a statement, the festival reps said: “After 6.30pm local time on Sunday, and although music did announcement on Twitter. Charli wrote: “My Gov Ball per- close consultation with NYC officials and law enforce- eventually get under way, the storms hit the site and the formance got cancelled due to potential storms so I’m put- ment, it was deemed necessary to evacuate the site and event was cancelled at around 9.30pm with punters told to ting on a last minute show tonight in Manhattan.” When a cancel the Sunday evening of Gov Ball 2019 for the safety leave immediately by the nearest exits. It meant the ‘Late fan suggested the event - which cost $15 a ticket - should of our festival goers, artists, and crew. The safety of every- Nite’ hitmakers weren’t able to perform, while fellow have been free to Governor Ball punters, the musician one always comes first.” headliner SZA also couldn’t play her set at the top of the agreed but said it couldn’t be done.