Migrant Workers at the Margin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kanpur Dehat

State: Uttar Pradesh Agriculture Contingency Plan for District: Kanpur Dehat 1.0 District Agriculture profile 1.1 Agro-Climatic/ Ecological Zone Agro-Ecological Sub Region(ICAR) Central Plain Zone Agro-Climatic Zone (Planning Commission) Upper Gangetic Plain Region Agro-Climatic Zone (NARP) UP-4 Central Plain Zone List all the districts falling the NARP Zone* (^ 50% area falling in the Lakhimpur Kheri, Sitapur, Hardoi, Farrukhabad, Etawah, Kanpur, Kanpur zone) Dehat, Unnao, Lucknow, Rae Bareilly, Fatehpur and Allahabad. Geographical coordinates of district headquarters Latitude Longitude Altitude(mt) 26.28 N 80.20 E Name and address of the concerned ZRS/ZARS/RARS/RRS/RRTTS Mention the KVK located in the district with address Krishi Vigyan Kendra, Zonal Agricultural Research Station, Daleep Nagar, Kanpur Dehat Name and address of the nearest Agromet Field Unit(AMFU,IMD)for CSA Kanpur agro advisories in the Zone 1.2 Rainfall Normal RF (mm) Normal Rainy Normal Onset Normal Cessation Days (Number) (Specify week and month) (Specify week and month) SW monsoon (June-sep) 713.1 45 3nd week of June 4th week of September Post monsoon (Oct-Dec) 38.1 10 Winter (Jan-March) 37.1 10 - - Pre monsoon (Apr-May) 13.2 2 - - Annual 801.5 67 - - 1.3 Land use pattern Geographical Cultivable Forest Land under Permanent Cultivable Land Barren and Current Other of the district area area area non- pastures wasteland under uncultivable fallows fallows (Latest agricultural Misc.tree land statistics) use crops and groves Area in (000 ha) 315.0 262.8 5.8 29.8 0.4 4.3 2.7 16.2 21.5 12.4 1.4 Major Soils Area(‘000 ha) Percent(%) of total Deep, fine soils moderately saline and sodic 71.0 27 % Deep, loamy soils 55.2 21 % Deep, loamy soils associated with sandy soils 79.1 30 % and eroded 1.5 Agricultural land use Area(‘000 ha) Cropping intensity (%) Net sown area 221.9 132.2 % Area sown more than once 71.5 Gross cropped area 293.4 1.6 Irrigation Area(‘000 ha) Net irrigation area 155.8 Gross irrigated area 201.0 Rain fed area 66.1 Sources of irrigation (gross irr. -

Problems and Prospects of Oilseeds Production in Uttar Pradesh

Study No. 137 Publication No. 185 Problems and Prospects of Oilseeds Production in Uttar Pradesh Prof. Ramendu Roy 2013 Agro-Economic Research Centre University of Allahabad Allahabad-211002 PREFACE India is an agrarian country because more than 70 per cent population of the country directly depends on agriculture and allied sectors. Agriculture is also backbone of economy of the country. A number of crops are grown in the country. Among the crops, wheat, rice, potato, sugarcane, cotton, vegetables etc are main crops of India. The pulses and oilseeds are also sown across the country. These are mostly rainfed crops. India was not self sufficient in food production prior to commencement of Green Revolution while it was self sufficient in pulses and oil seeds. India was importing huge quantity of food grains from global markets to meet food requirement of population of the country. Since the independence, the Government of India had paid maximum attention on agriculture sectors to pay maximum investment in this sector through Five Year Plan. The result of investment in agriculture sector was found very positive and significant. The role of green revolution was also very significant in boosting the production of wheat and rice. The production of wheat and rice has increased manifold due to introduction of green revolution. Now the country is not only sufficient in the production of wheat and rice rather these are being exported to foreign countries. The impact of green revolution was mostly confined to only wheat and rice. On account of this, the farmers have changed their cropping pattern in favour of rice and wheat crops. -

Final Attendance Sheet Statelevel

HMIS/MCTS State Level Training cum Review of Divison ‐ Allahabad, Chitrakootdham and Varanasi Training Dates : 18‐20 Dec. 2014 Participants List Sl. No. Division District Designation Name of Participant Moile NO. Email ID 1 Varanasi Varanasi Divisional PM Mr. Brijesh Mishra 8005192941 [email protected] 2 Varanasi Varanasi Div. Accounts Manager Mr. Sanjay Srivastava 8005193326 [email protected] 3 Varanasi Varanasi District Immunization Officer (DIO) Dr. B.N. Singh 9918902105 [email protected] 4 Varanasi Varanasi District Program Manager (DPM) Mr. Ripunjay Srivastava 8005193093 [email protected] 5 Varanasi Varanasi District Data Manager (DDM) Mr. Ritesh Kr. Srivastava 9307771956 [email protected] 6 Varanasi Varanasi District Asst. Research Office (ARO) Hari Bandhan Maurya [email protected] 7 Varanasi Varanasi HMIS Operator Pankaj Rai 9696898645 8 Varanasi Chandauli District Immunization Officer (DIO) Dr. H.R. Maurya 9648009462 [email protected] 9 Varanasi Chandauli District Program Manager (DPM) Dr. R.B. Yadav 8005193040 [email protected] 10 Varanasi Chandauli District Asst. Research Office (ARO) Vidyuta Prakash Singh 8005193255 [email protected] 11 Varanasi Chandauli HMIS Operator Nilratan 9889138764 [email protected] 12 Varanasi Ghazipur District Immunization Officer (DIO) Dr. S.K. Rai 9415624032 [email protected] 13 Varanasi Ghazipur District Program Manager (DPM) Mr. Satya Prakash 8005193051 [email protected] 14 Varanasi Ghazipur District Data Manager (DDM) Mohd. Azhar Khan 9451601062 [email protected] 15 Varanasi Ghazipur District Asst. Research Office (ARO) Dr. S.N. Chauhan 9415972968 [email protected] 16 Varanasi Ghazipur HMIS Operator Mr. Shiv Kumar Yadav 8808619132 [email protected] 17 Varanasi Jaunpur District Immunization Officer (DIO) Dr. -

Lower Ganga Canal Command Area and Haidergarh Branch Environmental Setting & Environmental Baseline 118

Draft Final Report of Lower Ganga Canal System and Public Disclosure Authorized Haidergarh Branch Public Disclosure Authorized REVISED Public Disclosure Authorized Submitted to: Project Activity Core Team (PACT) WALMI Bhawan, Utrethia, Telibagh, Lucknow – 226026 Submitted by: IRG Systems South Asia Pvt. Ltd. Lower Ground Floor, AADI Building, 2-Balbir Saxena Marg, Hauz Khas, Public Disclosure Authorized New Delhi – 110 016, INDIA Tel: +91-11-4597 4500 / 4597 Fax: +91-11-4175 9514 www.irgssa.com In association with Page | 1 Tetra Tech India Ltd. IRG Systems South Asia Pvt. Ltd. Table of Contents CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION 16 1.0 Introduction & Background 16 1.1 Water Resource Development in Uttar Pradesh 16 1.2 Study Area & Project Activities 20 1.3 Need for the Social & Environmental Framework 24 1.4 Objectives 24 1.5 Scope of Work (SoW) 25 1.6 Approach & Methodology 25 1.7 Work Plan 28 1.8 Structure of the Report 29 CHAPTER 2: REGULATORY REVIEW AND GAP ANALYSIS 31 2.0 Introduction 31 2.1 Policy and regulatory framework to deal with water management, social and environmental safeguards 31 2.1.2 Regulatory framework to deal with water, environment and social Safeguards 31 2.1.3 Legislative Framework to Deal with Social Safeguards 32 2.2 Applicable Policy, Rules & Regulation to project interventions / activities 33 2.2.1 EIA Notification 33 2.3 Institutional Framework to deal with water, social and environmental safeguards 37 2.4 Institutional Gaps 39 CHAPTER 3: SOCIO-ECONOMIC BASELINE STATUS 40 3.0 Introduction 40 3.1 Socio-Economic Baseline -

Summary Report 2020-11-17 05:00

SUMMARY REPORT 2020-11-17 05:00 Average Max Geofence Geofence Ignition Ignition Device Distance Spent Engine Start End Sr Speed Speed Start Address End Address In Out On Off Name (Kms) Fuel hours Time Time (Km/h) (Km/h) (times) (times) (times) (times) 2020- 2020- HR38T 1 0.15 0.0 0.1 0 0 h 2 m Sector 57, Faridabad, Haryana, 121001, India Sector 57, Faridabad, Haryana, 121001, India 11-16 11-16 0 0 1 1 1701 00:02:15 23:54:01 2020- 2020- HR38S Burhi Bawal - Dharuhera Rd, Banbeerpur, Burhi Bawal - Dharuhera Rd, Banbeerpur, 2 0.19 0.0 0.2 0 0 h 0 m 11-16 11-16 0 0 0 0 2313 Rajasthan 301707, India Rajasthan 301707, India 00:05:02 23:45:43 2020- 2020- HR38T Himgiri Colony, Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh Himgiri Colony, Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh 3 0.01 0.0 0.0 0 0 h 0 m 11-16 11-16 0 0 0 0 8585 244001, India 244001, India 00:10:49 23:56:09 2020- 2020- HR38S Industrial Area Khushkhera, Banebeerpur, Tijara Industrial Area Khushkhera, Banebeerpur, Tijara 4 0.05 0.0 0.0 0 0 h 0 m 11-16 11-16 0 0 0 0 2331 Tehsil, Alwar, Rajasthan, 301707, India Tehsil, Alwar, Rajasthan, 301707, India 00:13:39 23:48:54 2020- 2020- HR38S Unnamed Road, Sector 4, Palla No.1, Faridabad, Vashisht Niwas, Sector 4 Ballabhgarh (Shiv 5 0.07 0.0 0.0 0 0 h 0 m 11-16 11-16 0 0 0 0 2322 Haryana 121004, India Colony), Faridabad, Haryana-121004 India 00:14:23 23:59:16 2020- 2020- HP12D Unnamed Road, Sector 4, Palla No.1, Faridabad, Unnamed Road, Sector 4, Palla No.1, Faridabad, 6 0.01 0.0 0.0 0 0 h 0 m 11-16 11-16 0 0 0 0 7780 Haryana 121004, India Haryana 121004, India 00:06:40 23:51:51 -

Kanpur Dehat District, U.P

DISTRICT GROUND WATER BROCHURE KANPUR DEHAT DISTRICT, U.P. (AAP: 2012-13) By P.K. Tripathi Scientist 'C' CONTENTS Chapter Title Page No. KANPUR DEHAT DISTRICT AT A GLANCE ..................3 1.0 INTRODUCTION ..................6 2.0 RAINFALL & CLIMATE ..................7 3.0 GEOMORPHOLOGY & SOIL TYPE ..................7 4.0 GROUND WATER SCENARIO ..................8 4.1 Hydrogeology 4.2 Ground Water Resource 4.3 Ground Water Quality 4.4 Status of Ground Water Development 5.0 GROUND WATER MANAGEMENT STRATEGY ..................14 5.1 Ground Water Development 5.2 Water Conservation Structure & Artificial Recharge 6.0 GROUND WATER RELATED ISSUES AND PROBLEMS ..................15 7.0 RECOMMENDATIONS ..................16 PLATES: I. INDEX MAP OF KANPUR DEHAT DISTRICT, U.P. II. HYDROGEOMORPHOLOGICAL MAP OF KANPUR DEHAT DISTRICT, U.P. III. CANAL'S MAP OF KANPUR DEHAT, U.P. IV. FENCE DIAGRAM KANPUR DEHAT, U.P. V. DEPTH TO WATER LEVEL PREMONSOON 2012, KANPUR DEHAT DISTRICT, U.P. VI. DEPTH TO WATER LEVEL POSTMONSOON 2012, KANPUR DEHAT DISTRICT, U.P. VII. CATEGORIZATION OF BLOCKS (GROUND WATER RESOURCES /DRAFT), KANPUR DEHAT DISTRICT, U.P. VIII. ISOCON MAP AND POINT VALUES OF ARSENIC (PHREATIC AQUIFER), KANPUR DEHAT DISTRICT, U.P. APPENDIX: I. DETAILS OF EXPLORATORY TUBEWELLS IN KANPUR DEHAT DISTRICT, U.P. 2 KANPUR DEHAT DISTRICT AT GLANCE 1. GENERAL INFORMATION i. Geographical Area (Sq km.) : 3021 ii. Administrative Divisions : Number of Tehsil/Block 5/10 Number of Panchayat/Villages 102/1032 iii. Population (as on 2001 census) : 15,63,336 iv. Average Annual Rainfall (mm) : 782.8 2. GEOMORPHOLOGY Major Physiographic Units : Older Alluvium plain, older flood plain & active flood plain Major Drainages : Yamuna, Pandu, Rind, Sengar 3. -

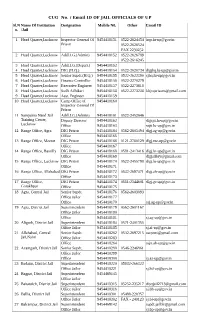

CUG No. / Email ID of JAIL OFFICIALS of up Sl.N Name of Institution Designation Mobile N0

CUG No. / Email ID OF JAIL OFFICIALS OF UP Sl.N Name Of Institution Designation Mobile N0. Other Email ID o. /Jail 1 Head Quarter,Lucknow Inspector General Of 9454418151 0522-2624454 [email protected] Prison 0522-2626524 FAX 2230252 2 Head Quarter,Lucknow Addl.I.G.(Admin) 9454418152 0522-2626789 0522-2616245 3 Head Quarter,Lucknow Addl.I.G.(Depart.) 9454418153 4 Head Quarter,Lucknow DIG (H.Q.) 9454418154 0522-2620734 [email protected] 5 Head Quarter,Lucknow Senior Supdt.(H.Q.) 9454418155 0522-2622390 [email protected] 6 Head Quarter,Lucknow Finance Controller 9454418156 0522-2270279 7 Head Quarter,Lucknow Executive Engineer 9454418157 0522-2273618 8 Head Quarter,Lucknow Sodh Adhikari 9454418158 0522-2273238 [email protected] 9 Head Quarter,Lucknow Asst. Engineer 9454418159 10 Head Quarter,Lucknow Camp Office of 9454418160 Inspector General Of Prison 11 Sampurna Nand Jail Addl.I.G.(Admin) 9454418161 0522-2452646 Training Center, Deputy Director 9454418162 [email protected] Lucknow Office 9454418163 [email protected] 12 Range Office, Agra DIG Prison 9454418164 0562-2605494 [email protected] Office 9454418165 13 Range Office, Meerut DIG Prison 9454418166 0121-2760129 [email protected] Office 9454418167 14 Range Office, Bareilly DIG Prison 9454418168 0581-2413416 [email protected] Office 9454418169 [email protected] 15 Range Office, Lucknow DIG Prison 9454418170 0522-2455798 [email protected] Office 9454418171 16 Range Office, Allahabad DIG Prison 9454418172 0532-2697471 [email protected] Office 9454418173 17 Range Office, DIG Prison 9454418174 0551-2344601 [email protected] Gorakhpur Office 9454418175 18 Agra, Central Jail Senior Supdt. -

INDIA Public Disclosure Authorized

E-339 VOL. 1 INDIA Public Disclosure Authorized THIRD NATIONAL HIGHWAY WORLD BANK PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized CONSOLIDATED EIA REPORT (CONSTRUCTION PACKAGES 11- V) Public Disclosure Authorized NATIONAL HIGHWAYS AUTHORITY OF INDIA NEW DELHI (Ministry of Surface Transport) March, 2000 Public Disclosure Authorized 4 4 =fmmm~E-339 VOL. 1 INDIA THIRD NATIONAL HIGHWAY WORLD BANK PROJECT CONSOLIDATED EIA REPORT (CONSTRUCTION PACKAGES II - V) NATIONAL HIGHWAYS AUTHORITY OF INDIA NEW DELHI (Ministry of Surface Transport) March, 2000 TABLE OF CONTENTS THE REPORT I The Project............................................................... 1-1 1.1 The Project Description ............................................................... ]-II 1.2 Overall Scope of Project Works ............................................................ 1-3 1.3 Proposed Improvement of the Project Highway ................... ................ 1-3 1.4 Scope of Environmental Impact Assessment ................. ........................... 1-6 1.5 Structure of The Consolidated EIA Report ........................................... 1-7 2 Policy, Legal And Administrative Framework ................... ........................... 2-1 2.1 Institutional Setting for the Project .. 2-1 2.1.1 The National Highways Authority of India (NHAI) 2-1 2.1.2 Project Implementation Units (PIU) .................................................. 2-1 2.1.3 State Public Works Departments (PWDs) .2-2 2.2 Institutional Setting in the Environmental Context .................... 2-2 2.2.1 Ministry -

Evcc`C Decz\V ` :27 Hzey Uc` Vd

% ( )&-6#,&$# $&1&+,&(&-&.+6&-$ 4&1$# &-/*-$ &)*+,-./ 0). #0)+0#-&$/#1 1#-)*1#* +1 )#-*2#1) &1$.-.6 && (.+-#0+$$. $31*#-21#- 1*7 &)1#+- )3&1#0#4*5#3/## ! "#$%&# !" ##$#%& ' () !" &( -&/&)* #"$ he helicopters of the IAF Tare believed to be the obvi- "$"% ous target of Sunday’s drone attack on the Air Force Station, ,+ , - 5#66+ Jammu, considered one of the most strategic and valuable wo back-to-back explosions assets of the Indian Air Force Twere reported from inside (IAF), located barely 14 kms the fortified Air Force Station from the International Border in Jammu, past Saturday mid- (IB) with Pakistan. night as the strategic asset came As the probe into the inci- under a drone attack. dent is on, IAF chief RKS Two IAF personnel received Bhadauria, who is in injuries while the rooftop of a Bangladesh at the moment, is building was damaged in the monitoring the situation. explosion which was heard in a Defence Minister Rajnath Singh radius of over one kilometer. The was also briefed on Sunday ‘provocative’ attack was aimed at morning about the terror attack. targeting the IAF assets parked Initial reports suggest that the at the Air Force Station. drone attack may have been car- In a series of tweets the ried out from across the border. Indian Air Force (IAF) Rated to be one of the most informed that two low-inten- sensitive airbases in the coun- sity explosions were reported in !" # $ % ! '( try, the Jammu airfield has a the technical area of Jammu Air sizable number of rotary wing * ! + Force Station. &(*&+ +,-./,#- +1 gesture, after landing at the the country. -

Basic Information of Urban Local Bodies – Uttar Pradesh

BASIC INFORMATION OF URBAN LOCAL BODIES – UTTAR PRADESH As per 2006 As per 2001 Census Election Name of S. Growth Municipality/ Area No. of No. Class House- Total Rate Sex No. of Corporation (Sq. Male Female SC ST (SC+ ST) Women Rate Rate hold Population (1991- Ratio Wards km.) Density Membe rs 2001) Literacy 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 I Saharanpur Division 1 Saharanpur District 1 Saharanpur (NPP) I 25.75 76430 455754 241508 214246 39491 13 39504 21.55 176 99 887 72.31 55 20 2 Deoband (NPP) II 7.90 12174 81641 45511 36130 3515 - 3515 23.31 10334 794 65.20 25 10 3 Gangoh (NPP) II 6.00 7149 53913 29785 24128 3157 - 3157 30.86 8986 810 47.47 25 9 4 Nakur (NPP) III 17.98 3084 20715 10865 9850 2866 - 2866 36.44 1152 907 64.89 25 9 5 Sarsawan (NPP) IV 19.04 2772 16801 9016 7785 2854 26 2880 35.67 882 863 74.91 25 10 6 Rampur Maniharan (NP) III 1.52 3444 24844 13258 11586 5280 - 5280 17.28 16563 874 63.49 15 5 7 Ambehta (NP) IV 1.00 1739 13130 6920 6210 1377 - 1377 27.51 13130 897 51.11 12 4 8 Titron (NP) IV 0.98 1392 10501 5618 4883 2202 - 2202 30.53 10715 869 54.55 11 4 9 Nanauta (NP) IV 4.00 2503 16972 8970 8002 965 - 965 30.62 4243 892 60.68 13 5 10 Behat (NP) IV 1.56 2425 17162 9190 7972 1656 - 1656 17.80 11001 867 60.51 13 5 11 Chilkana Sultanpur (NP) IV 0.37 2380 16115 8615 7500 2237 - 2237 27.42 43554 871 51.74 13 5 86.1 115492 727548 389256 338292 65600 39 65639 23.38 8451 869 67.69 232 28 2 Muzaffarnagar District 12 Muzaffarnagar (NPP) I 12.05 50133 316729 167397 149332 22217 41 22258 27.19 2533 892 72.29 45 16 13 Shamli -

File No. 4160

** Just to reduce the size , all the figures are removed ** Annexures are appended already along with Form-01 Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) Report with Regional Environment Management Plan (REMP) for Morrum Mining from Riverbed of Yamuna River Located at Khand No (s). K-2, Gata No.- 389Mi, 390Mi, Village- Kharka, Tehsil- Bhognipur, District – Kanpur Dehat Sanctioned Area – 18.33 ha. Proposed Production of Morrum – 274950.0 m3/year Prepared on the basis of TOR issued by SEAC, UP File No. 4160 Submitted by: M/s Harihar Minerals LLP Proprietor – Shri Ram Autar Singh S/o Shri Tejram Singh Address – New Patel Nagar, Orai, Jalaun (U.P.) Submitted to State Level Environment Impact Assessment Authority, U.P. Directorate of Environment, Govt. U.P. Baseline Consultant Research Institute of Material Sciences, New Delhi Environment Consultant ENV Developmental Assistance Systems (India) Pvt. Ltd. Lucknow (QCI-NABET Accredited for Category ‘A’ Projects) D-2247, Indira Nagar, Lucknow-226016, Ph: +91 522 4007470, 4107624 TeleFax: 0522 4021236 Email: [email protected], Website: www.dasindia.org October, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS S. NO. CONTENTS I TOR COMPLIANCE II PH COMPLIANCE CHAPTER-1 1.1 GENERAL 1.1.1 Sand mining in India 1.1.2 Present status of sand Mining 1.1.3 Sand Mining in Uttar Pradesh b Baseline Data Collection conforms to the BIS guidelines c Regional Environment Management Plan (REMP) 1.2.2 Recommendation for The Group of River Bed Mining Projects 1.3 LEGISLATION APPLICABLE TO MINING OF MINOR MINERALS 1.3.1 Legislations 1.4 EXTRACT OF EIA NOTIFICATION 1.4.1 Environmental Clearance 1.4.2 Objective of EIA Study 1.5 PROJECT / PROPONENT DETAILS 1.5.1 Details of Project and Project Proponents in the study area 1.5.2 Brief description of nature, size, location of the project and its imoportance to the country, region a Nature b Brief history of projects in the study area c Size d Area and categorization of Projects in the study area 1.5.3 Location, brief description of project & its topography and physiography a. -

Uttar Pradesh 1.District: Kaushambi Major Observations of Regional

Uttar Pradesh 1.District: Kaushambi Major observations of Regional Evaluation Team, Lucknow about the Evaluation work in Kaushambi district of Uttar Pradesh in May, 2011 I. Details of the visited Institutions: District visited PHCs/CHCs visited SCs visited Kaushambi CHCs: Kanaili and Sirathu Itaila, Mayhar, Anetha, Malaksaddi, PHC: Chayal Salahpur and Manauri II.Major observations 1. Health Human Resources: a. In the Medical category, 20 posts of MO out of 73 sanctioned and 2 posts of specialist out of 15 sanctioned were lying vacant in the district. b. In the Para-medical category, 35 posts of ANM (out of 204 sanctioned), 63 posts of MPW (M) (out of 83 sanctioned), 23 posts of Health Supervisor (M) (out of 32 sanctioned) and 23 posts of Staff Nurse/GNM (out of 33 sanctioned) were also lying vacant. c. In the visited CHC, Kanaili, 5 of the 23 sanctioned posts of ANM, 8 of the 9 sanctioned posts of MPW (M), 4 of the 6 sanctioned posts of Health Supervisor (M), 1 of the 3 sanctioned posts of Staff Nurse and 1 of the 5 sanctioned posts of specialist were lying vacant. In CHC, Sirathu 2 of the 25 sanctioned posts of ANM, 9 of the 12 sanctioned posts of MPW (M), 5 of the 7 sanctioned posts of Health Supervisor (M), 3 of the 5 sanctioned posts of Staff Nurse, 4 of the 12 sanctioned posts of Medical Officer and 1 of the 5 sanctioned posts of specialist were lying unfilled. d. 2 of the 27 sanctioned posts of ANM, 11 of the 13 sanctioned posts of MPW (M), 5 of the 7 sanctioned posts of Health Supervisor (M) and 2 of the 8 sanctioned posts of Medical Officer in PHC Chayal were lying vacant.