The Right to the Slum? Redevelopment, Rule and the Politics of Difference in Mumbai

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1. INTRODUCTION the Importance of River Can Be Traced Way Back Into

1. INTRODUCTION The importance of river can be traced way back into history. The nomadic Stone Age man always wandered around rivers. The world’s greatest civilizations have flourished on the banks of rivers. The Nile River was a key for the development of Ancient Egypt, the Indus River for the development of Mohenjo-Daro civilization, the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers for the development of Mesopotamian cultures, the Tiber River for Ancient Rome, etc. Ever since man learnt the benefits of rivers, he has used the river for various purposes like drinking, domestic use, irrigation, navigation, fishing, etc. As man advanced he invented new techniques to exploit river waters. With the advent of industrialization, the river water was now being used as a way to dispose of industrial waste, sewage and other domestic waste. Today, success of human civilization in developing or under developing countries mostly depends upon its industrial productivity that leads to economic progress of the country. Urbanization, globalization and industrialization all have an indirect or not specifically intended effect on ecosystem (Tanner et al., 2001). The disposal of human waste is another great challenge in both developed and developing countries (Zimmel et al. 2004).Waterways have been considered as convenient, cheapest and effective path for disposal of human waste. Aquatic ecosystems have been threatened worldwide by pollution and non unsustainable land use. Effect of poor quality of water on human health was noted first time in1854 by John Snow when he traced the outburst of cholera epidemic in London Thames River which was polluted to a great extent by sewage. -

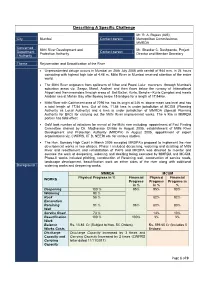

Describing a Specific Challenge

Describing A Specific Challenge Mr. R. A. Rajeev (IAS), City Mumbai Contact person Metropolitan Commissioner, MMRDA Concerned Mithi River Development and Mr. Shankar C. Deshpande, Project Department Contact person Protection Authority Director and Member Secretary / Authority Theme Rejuvenation and Beautification of the River • Unprecedented deluge occurs in Mumbai on 26th July 2005 with rainfall of 944 mm. in 24 hours coinciding with highest high tide of 4.48 m. Mithi River in Mumbai received attention of the entire world. • The Mithi River originates from spillovers of Vihar and Powai Lake traverses through Mumbai's suburban areas viz. Seepz, Marol, Andheri and then flows below the runway of International Airport and then meanders through areas of Bail Bazar, Kurla, Bandra - Kurla Complex and meets Arabian sea at Mahim Bay after flowing below 15 bridges for a length of 17.84Km. • Mithi River with Catchment area of 7295 ha. has its origin at 246 m. above mean sea level and has a total length of 17.84 kms. Out of this, 11.84 kms is under jurisdiction of MCGM (Planning Authority as Local Authority) and 6 kms is under jurisdiction of MMRDA (Special Planning Authority for BKC) for carrying out the Mithi River improvement works. The 6 Km in MMRDA portion has tidal effect. • GoM took number of initiatives for revival of the Mithi river including appointment of Fact Finding Committee chaired by Dr. Madhavrao Chitale in August 2005, establishment of Mithi River Development and Protection Authority (MRDPA) in August 2005, appointment of expert organisations viz. CWPRS, IIT B, NEERI etc. for various studies. -

707LTD Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

707LTD bus time schedule & line map 707LTD Goregaon Depot (Oshiwara Depot) - View In Website Mode Bhayander Railway Station (E) The 707LTD bus line (Goregaon Depot (Oshiwara Depot) - Bhayander Railway Station (E)) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Bhayander Railway Station (E): 4:55 AM - 9:50 PM (2) Goregaon Depot (Oshiwara Depot): 6:00 AM - 11:15 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 707LTD bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 707LTD bus arriving. Direction: Bhayander Railway Station (E) 707LTD bus Time Schedule 90 stops Bhayander Railway Station (E) Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 4:55 AM - 9:50 PM Monday 4:55 AM - 9:50 PM Goregaon Oshiwara Depot Tuesday 4:55 AM - 9:50 PM Bhagatsingh Nagar Wednesday 4:55 AM - 9:50 PM Shastri Nagar Thursday 4:55 AM - 9:50 PM Bangur Ngr Police Chowky / Post O∆ce Friday 4:55 AM - 9:50 PM Bangur Nagar Saturday 4:55 AM - 9:50 PM Inorbit Mall Chinchowali Bandar Link Road, Mumbai Inorbit Mall 707LTD bus Info Direction: Bhayander Railway Station (E) Vinay Industry (Subkuch Market) Stops: 90 Trip Duration: 68 min Goregaon Link Road, Mumbai Line Summary: Goregaon Oshiwara Depot, Nirlon Society Bhagatsingh Nagar, Shastri Nagar, Bangur Ngr Police Chowky / Post O∆ce, Bangur Nagar, Inorbit Mall, Inorbit Mall, Vinay Industry (Subkuch Market), Chincholi Bunder Road Nirlon Society, Chincholi Bunder Road, Chincholi Bunder Junction, Malad Depot, D Mart Shopping Chincholi Bunder Junction Centre, Kach Pada, Evershine Nagar, Mith Chowky Malad, Mith Chowky, Orlem -

Periodical Report Periodical Report

ICTICT IncideIncidentsnts DatabaseDatabase PeriodicalPeriodical ReportReport January 2012 2011 The following is a summary and analysis of terrorist attacks and counter-terrorism operations that occurred during the month of January 2012, researched and recorded by the ICT database team. Among others: Irfan Ul Haq, 37 was sentenced to 50 months in prison on 5 January, for providing false documentation and attempting to smuggle a suspected Taliban member into the USA. On 5 January, Eyad Rashid Abu Arja, 47, a male Palestinian with dual Australian-Jordanian nationality, was sentenced to 30 months in prison in Israel for aiding Hamas. On 6 January, a bomb exploded in Damascus, Syria killing 26 people and wounding 63 others. ETA militant Andoni Zengotitabengoa, was sentenced on 6 January to 12 years in prison for the illegal possession of weapons, as well car theft, falsification of documents, assault and resisting arrest. On 9 January, Sami Osmakac, 25, was charged with plotting to attack crowded locations in Florida, USA. On 10 January, a car bomb exploded at a bus stand outside a shopping bazaar in Jamrud, northwestern Pakistan killing 26 people and injuring 72. Jermaine Grant, 29, a British man and three Kenyans were charged on 13 January in Mombasa, Kenya with possession of bomb-making materials and plotting to explode a bomb. On 13 January Thai police arrested Hussein Atris, 47, a Lebanese-Swedish man, who was suspected of having links to Hizballah. He was charged three days later with the illegal possession of explosive materials. On 14 January, a suicide bomber, disguised in a military uniform, killed 61 people and injured 139, at a checkpoint outside Basra, Iraq. -

165 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

165 bus time schedule & line map 165 Dharavi Depot - Kasturba Gandhi Chowk [C.P.Tank] View In Website Mode The 165 bus line (Dharavi Depot - Kasturba Gandhi Chowk [C.P.Tank]) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Dharavi Depot: 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM (2) Kasturba Gandhi Chowk (C.P.Tank): 4:20 AM - 11:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 165 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 165 bus arriving. Direction: Dharavi Depot 165 bus Time Schedule 51 stops Dharavi Depot Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM Monday 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM Kasturba Gandhi Chowk (C.P.Tank) / कतुरबा गांधी चौक (सी.पी.टॅंक) Tuesday 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM Gulal Wadi / Yadnik Chowk Wednesday 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM Brig Usman Marg (Erskine Road), Mumbai Thursday 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM Alankar Cinema Friday 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM Dr M G Mahimtura Marg (Northbrook Street), Mumbai Saturday 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM Khambata Lane / Alankar Cinema Khambata Lane 254/264 Patthe Bapurao Marg (Falkland Road), Mumbai 165 bus Info Anjuman College Direction: Dharavi Depot Stops: 51 Two Tanks Trip Duration: 42 min Line Summary: Kasturba Gandhi Chowk (C.P.Tank) / Hasrat Mohani Chowk कतुरबा गांधी चौक (सी.पी.टॅंक), Gulal Wadi / Yadnik Maulana Azad Road (Duncan Road), Mumbai Chowk, Alankar Cinema, Khambata Lane / Alankar Cinema, Khambata Lane, Anjuman College, Two Madanpura Tanks, Hasrat Mohani Chowk, Madanpura, Salvation Army Nagpada, New Agripada, Hindustan Mill, Sant Salvation Army Nagpada Gadge Maharaj Chowk, Mahalaxmi Railway Station, -

Dharavi, Mumbai: a Special Slum?

The Newsletter | No.73 | Spring 2016 22 | The Review Dharavi, Mumbai: a special slum? Dharavi, a slum area in Mumbai started as a fishermen’s settlement at the then outskirts of Bombay (now Mumbai) and expanded gradually, especially as a tannery and leather processing centre of the city. Now it is said to count 800,000 inhabitants, or perhaps even a million, and has become encircled by the expanding metropolis. It is the biggest slum in the city and perhaps the largest in India and even in Asia. Moreover, Dharavi has been discovered, so to say, as a vote- bank, as a location of novels, as a tourist destination, as a crime-site with Bollywood mafiosi skilfully jumping from one rooftop to the other, till the ill-famous Slumdog Millionaire movie, and as a planned massive redevelopment project. It has been given a cult status, and paraphrasing the proud former Latin-like device of Bombay’s coat of arms “Urbs Prima in Indis”, Dharavi could be endowed with the words “Slum Primus in Indis”. Doubtful and even treacherous, however, are these words, as the slum forms primarily the largest concentration of poverty, lack of basic human rights, a symbol of negligence and a failing state, and inequality (to say the least) in Mumbai, India, Asia ... After all, three hundred thousand inhabitants live, for better or for worse, on one square km of Dharavi! Hans Schenk Reviewed publication: on other categories of the population, in terms of work, caste, the plans to the doldrums.1 Under these conditions a new Saglio-Yatzimirsky, M.C. -

Final Report

Studying the association between structural factors and tuberculosis in the resettlement colonies in M-East ward, Mumbai Final Report Doctors For You July 2018 Contents Description Page no. Executive Summary 3 Introduction 6 Aim 8 Objectives 8 Methodology 10 Results 18 Discussion 7754 Recommendations 7877 Conclusion and Future Prospects 8079 References 8281 2 Executive Summary The building architecture and site planning seems to play a big role in creating a healthy atmosphere in the urban resettlement colonies as is projected by the various reports on research carried out in different countries (1-14). High burden of TB results in sizeable economic and social costs making it a critical issue to address. Hence, it is worthwhile to study if the urban resettlement colonies in M-East ward also show similar trends. Further, it is important to consider if the Development Control Regulations (DCRs) for resettlement buildings need to be changed in order to ensure that the health of the families residing in these buildings is not compromised due to any design and layout faults. Through this study, we aimed to investigate and establish the strength of association between structural factors of slums resettlement colonies buildings and the incidence pattern of tuberculosis. For this, we performed a cross sectional study using household survey to find architectural and socioeconomic details of the household, computational modelling of sunlight and ventilation access based on house design and layout of the Lallubhai compound, Natwar Parekh compound and PMG colony and validation of these models by actual measurements of air velocity and daylight. Results: Computation modelling has shown that lower floors do not have access to sufficient light (Fig. -

Infrastructure As Method (Supplementary Chapter for Pipe Politics, Contested Waters)

Infrastructure as Method (Supplementary chapter for Pipe Politics, Contested Waters) Lisa Björkman This supplementary chapter outlines the research design and methodology that animated the fieldwork for Pipe Politics, Contested Waters. In surveying this methodological terrain, I show shows how water infrastructures were simultaneously an object of inquiry, as well as the medium and methodological entryway for studying those same processes. The chapter attends to some of the challenges – material, practical, epistemological – that I encountered and navigated in the field, probing some key aspects of ethnographic research design and practice that can sometimes go unspoken: framing a research question; figuring out how and where to go looking for answers; trying out different strategies; adjusting, adapting, experimenting, and even sometimes discarding particular techniques when they prove misguided or unhelpful. While these sorts of discussions are generally edited out of published manuscripts – as indeed it is in Pipe Politics – I offer them here to make a separate argument regarding the relationship between ethnography and methodology. Ethnographers of the global present face particular methodological challenges – challenges that have perhaps always haunted the ethnographic enterprise, but that have bubbled to the sociological surface lately in especially demanding ways. To state the problem simply: how can a methodology (i.e., ethnography) that is premised on the production of knowledge through immersion in ‘local’ worlds be put to work -

Slum Dwellers International (SDI)

Slum Dwellers International (SDI) Skoll Entrepreneur(s): Jockin Arputham Award Year: 2014 Focus Area(s) Addressed: Education and Economic Opportunity, Water and Sanitation “Leading Slum Dwellers around the World to Improve Their Cities” In 2008—for the first time in history— more people were living in urban than in rural areas. Today, more than one billion people live in slums. Founded by a collective of slum dwellers and concerned professionals headed by Jockin Arputham, a community organizer in India, Slum Dwellers International works to have slums recognized as vibrant, resourceful, and dignified communities. SDI organizes slum dwellers to take control of their futures; improve their living conditions; and gain recognition as equal partners with governments and international organizations in the creation of inclusive cities. With programs in nearly 500 cities, including more than 15,000 slum dweller-managed savings groups reaching one million people; 20 agreements with national governments; and nearly 130,000 families who have secured land rights, SDI has been a driving force for change for slum dwellers around the world. Jockin Arputham is the president of the National Slum Dwellers Federation of India, which he founded in the 1970s. Often referred to as the “grandfather” of the global slum dwellers movement, Jockin was educated by the slums, living on the streets for much of his childhood with no formal education. For more than 30 years, Jockin has worked in slums and shanty towns throughout India and around the world. After working as a carpenter in Mumbai, he became involved in organizing the community where he lived and worked. -

India 2020 Crime & Safety Report: Mumbai

India 2020 Crime & Safety Report: Mumbai This is an annual report produced in conjunction with the Regional Security Office at the U.S. Consulate General in Mumbai. OSAC encourages travelers to use this report to gain baseline knowledge of security conditions in India. For more in-depth information, review OSAC’s India-specific webpage for original OSAC reporting, consular messages, and contact information, some of which may be available only to private-sector representatives with an OSAC password. Travel Advisory The current U.S. Department of State Travel Advisory at the date of this report’s publication assesses most of India at Level 2, indicating travelers should exercise increased caution due to crime and terrorism. Some areas have increased risk: do not travel to the state of Jammu and Kashmir (except the eastern Ladakh region and its capital, Leh) due to terrorism and civil unrest; and do not travel to within ten kilometers of the border with Pakistan due to the potential for armed conflict. Review OSAC’s report, Understanding the Consular Travel Advisory System Overall Crime and Safety Situation The Consulate represents the United States in Western India, including the states of Maharashtra, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, and Goa. Crime Threats The U.S. Department of State has assessed Mumbai as being a MEDIUM-threat location for crime directed at or affecting official U.S. government. Although it is a city with an estimated population of more than 25 million people, Mumbai remains relatively safe for expatriates. Being involved in a traffic accident remains more probable than being a victim of a crime, provided you practice good personal security. -

Mahead-Dec2019.Pdf

MAHAPARINIRVAN DAY 550TH BIRTH ANNIVERSARY: GURU NANAK DEV CLIMATE CHANGE VS AGRICULTURE VOL.8 ISSUE 11 NOVEMBER–DECEMBER 2019 ` 50 PAGES 52 Prosperous Maharashtra Our Vision Pahawa Vitthal A Warkari couple wishes Chief Minister Uddhav Thackeray after taking oath as the Chief Minister of Maharashtra. (Pahawa Vitthal is a pictorial book by Uddhav Thackeray depicting the culture and rural life of Maharashtra.) CONTENTS What’s Inside 06 THIS IS THE MOMENT The evening of the 28th November 2019 will be long remem- bered as a special evening in the history of Shivaji Park of Mumbai. The ground had witnessed many historic moments in the past with people thronging to listen to Shiv Sena Pramukh, Late Balasaheb Thackeray, and Udhhav Thackeray. This time, when Uddhav Thackeray took the oath as the Chief Minister of Maharashtra on this very ground, the entire place was once again charged with enthusiasm and emotions, with fulfilment seen in every gleaming eye and ecstasy on every face. Maharashtra Ahead brings you special articles on the new Chief Minister of Maharashtra, his journey as a politi- cian, the new Ministers, the State Government's roadmap to building New Maharashtra, and the newly elected members of the Maharashtra Legislative Assembly. 44 36 MAHARASHTRA TOURISM IMPRESSES THE BEACON OF LONDON KNOWLEDGE Maharashtra Tourism participated in the recent Bharat Ratna World Travel Market exhibition in London. A Dr Babasaheb Ambedkar platform to meet the world, the event helped believed that books the Department reach out to tourists and brought meaning to life. tourism-related professionals and inform them He had to suffer and about the tourism attractions and facilities the overcome acute sorrow State has. -

IDL-56493.Pdf

Changes, Continuities, Contestations:Tracing the contours of the Kamathipura's precarious durability through livelihood practices and redevelopment efforts People, Places and Infrastructure: Countering urban violence and promoting justice in Mumbai, Rio, and Durban Ratoola Kundu Shivani Satija Maps: Nisha Kundar March 25, 2016 Centre for Urban Policy and Governance School of Habitat Studies Tata Institute of Social Sciences This work was carried out with financial support from the UK Government's Department for International Development and the International Development Research Centre, Canada. The opinions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect those of DFID or IDRC. iv Acknowledgments We are grateful for the support and guidance of many people and the resources of different institutions, and in particular our respondents from the field, whose patience, encouragement and valuable insights were critical to our case study, both at the level of the research as well as analysis. Ms. Preeti Patkar and Mr. Prakash Reddy offered important information on the local and political history of Kamathipura that was critical in understanding the context of our site. Their deep knowledge of the neighbourhood and the rest of the city helped locate Kamathipura. We appreciate their insights of Mr. Sanjay Kadam, a long term resident of Siddharth Nagar, who provided rich history of the livelihoods and use of space, as well as the local political history of the neighbourhood. Ms. Nirmala Thakur, who has been working on building awareness among sex workers around sexual health and empowerment for over 15 years played a pivotal role in the research by facilitating entry inside brothels and arranging meetings with sex workers, managers and madams.