Infrastructure As Method (Supplementary Chapter for Pipe Politics, Contested Waters)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

165 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

165 bus time schedule & line map 165 Dharavi Depot - Kasturba Gandhi Chowk [C.P.Tank] View In Website Mode The 165 bus line (Dharavi Depot - Kasturba Gandhi Chowk [C.P.Tank]) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Dharavi Depot: 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM (2) Kasturba Gandhi Chowk (C.P.Tank): 4:20 AM - 11:40 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 165 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 165 bus arriving. Direction: Dharavi Depot 165 bus Time Schedule 51 stops Dharavi Depot Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM Monday 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM Kasturba Gandhi Chowk (C.P.Tank) / कतुरबा गांधी चौक (सी.पी.टॅंक) Tuesday 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM Gulal Wadi / Yadnik Chowk Wednesday 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM Brig Usman Marg (Erskine Road), Mumbai Thursday 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM Alankar Cinema Friday 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM Dr M G Mahimtura Marg (Northbrook Street), Mumbai Saturday 12:00 AM - 11:40 PM Khambata Lane / Alankar Cinema Khambata Lane 254/264 Patthe Bapurao Marg (Falkland Road), Mumbai 165 bus Info Anjuman College Direction: Dharavi Depot Stops: 51 Two Tanks Trip Duration: 42 min Line Summary: Kasturba Gandhi Chowk (C.P.Tank) / Hasrat Mohani Chowk कतुरबा गांधी चौक (सी.पी.टॅंक), Gulal Wadi / Yadnik Maulana Azad Road (Duncan Road), Mumbai Chowk, Alankar Cinema, Khambata Lane / Alankar Cinema, Khambata Lane, Anjuman College, Two Madanpura Tanks, Hasrat Mohani Chowk, Madanpura, Salvation Army Nagpada, New Agripada, Hindustan Mill, Sant Salvation Army Nagpada Gadge Maharaj Chowk, Mahalaxmi Railway Station, -

Dharavi, Mumbai: a Special Slum?

The Newsletter | No.73 | Spring 2016 22 | The Review Dharavi, Mumbai: a special slum? Dharavi, a slum area in Mumbai started as a fishermen’s settlement at the then outskirts of Bombay (now Mumbai) and expanded gradually, especially as a tannery and leather processing centre of the city. Now it is said to count 800,000 inhabitants, or perhaps even a million, and has become encircled by the expanding metropolis. It is the biggest slum in the city and perhaps the largest in India and even in Asia. Moreover, Dharavi has been discovered, so to say, as a vote- bank, as a location of novels, as a tourist destination, as a crime-site with Bollywood mafiosi skilfully jumping from one rooftop to the other, till the ill-famous Slumdog Millionaire movie, and as a planned massive redevelopment project. It has been given a cult status, and paraphrasing the proud former Latin-like device of Bombay’s coat of arms “Urbs Prima in Indis”, Dharavi could be endowed with the words “Slum Primus in Indis”. Doubtful and even treacherous, however, are these words, as the slum forms primarily the largest concentration of poverty, lack of basic human rights, a symbol of negligence and a failing state, and inequality (to say the least) in Mumbai, India, Asia ... After all, three hundred thousand inhabitants live, for better or for worse, on one square km of Dharavi! Hans Schenk Reviewed publication: on other categories of the population, in terms of work, caste, the plans to the doldrums.1 Under these conditions a new Saglio-Yatzimirsky, M.C. -

Final Report

Studying the association between structural factors and tuberculosis in the resettlement colonies in M-East ward, Mumbai Final Report Doctors For You July 2018 Contents Description Page no. Executive Summary 3 Introduction 6 Aim 8 Objectives 8 Methodology 10 Results 18 Discussion 7754 Recommendations 7877 Conclusion and Future Prospects 8079 References 8281 2 Executive Summary The building architecture and site planning seems to play a big role in creating a healthy atmosphere in the urban resettlement colonies as is projected by the various reports on research carried out in different countries (1-14). High burden of TB results in sizeable economic and social costs making it a critical issue to address. Hence, it is worthwhile to study if the urban resettlement colonies in M-East ward also show similar trends. Further, it is important to consider if the Development Control Regulations (DCRs) for resettlement buildings need to be changed in order to ensure that the health of the families residing in these buildings is not compromised due to any design and layout faults. Through this study, we aimed to investigate and establish the strength of association between structural factors of slums resettlement colonies buildings and the incidence pattern of tuberculosis. For this, we performed a cross sectional study using household survey to find architectural and socioeconomic details of the household, computational modelling of sunlight and ventilation access based on house design and layout of the Lallubhai compound, Natwar Parekh compound and PMG colony and validation of these models by actual measurements of air velocity and daylight. Results: Computation modelling has shown that lower floors do not have access to sufficient light (Fig. -

MUMBAI METROPOLITAN REGION DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY 4 U 1Jq TIWF4TI- ET Wk T Fwetu Nil [ T 1

MUMBAI METROPOLITAN REGION DEVELOPMENT AUTHORITY 4 U _1jq TIWF4TI- ET Wk T fWETu nil [ T 1 IMRDA/ MUTP/ Post-R&R/ 2008/.35$ Date: - 2l September 9008 Public Disclosure Authorized 1 . Mir. t-lubert Nove Josserand The World Banik Ne\ Delhi Office 70. 1.odi Fstate, New Delhi 110003, INDIA. Subject: - Submission of Final Report on Impact Assessment of Resettlemiient Implementation under MUTP by Tata Institute of Social Public Disclosure Authorized Sciences (TISS). L)ear Sir, Please find hierewith the enclosed copy of final Report of Impact Assessment of' resettlement under MUTP by Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS). YourlS truly, Public Disclosure Authorized A .S.idaka Chief Post- R&R llCI: - copy of final Report submitted by TISS. CC: - I. I.U.B. Reddy, Senior Social Development Specialist. 2. Satya Mishra, World Bank Consultant. Public Disclosure Authorized FILE(S) - F ACTION BY U COPIED TO - - Bandra-Kurla Complex, Bandra (East), Mumbai - 400 051. org EPBX 2659 0001-08 12659 4000 * FAX: 2659 1264 * E-MAIL: mmrdaqgiasbm01.vsnI.netin * WEB SITE http://www.mmrdamumbat Impact Assessment of Resettlement Implementations under Mumbai Urban Transport Project (MUTP) .ALL i .t. Preparedby "S)Tata Institute of Social Sciences for The Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA) March 2008 TISS PROJECT TEAM Prof R.N. Sharma Team Leader Prof. K. Sita Consultant Ms. Leena Shevade Consultant-Engineer (TCE) Dr. Mouleshri Vyas Faculty Member Dr. Manish Jha Faculty Member Dr. A. Shaban Faculty Member Research Staff Ms. Harshada Pathare Research Assistant Ms. Thamilarasi A. Ramaiah Research Assistant Ms. Lata Nair : Research Assistant Mr. Surendra Rote : Research Assistant Ms. -

IDL-56493.Pdf

Changes, Continuities, Contestations:Tracing the contours of the Kamathipura's precarious durability through livelihood practices and redevelopment efforts People, Places and Infrastructure: Countering urban violence and promoting justice in Mumbai, Rio, and Durban Ratoola Kundu Shivani Satija Maps: Nisha Kundar March 25, 2016 Centre for Urban Policy and Governance School of Habitat Studies Tata Institute of Social Sciences This work was carried out with financial support from the UK Government's Department for International Development and the International Development Research Centre, Canada. The opinions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect those of DFID or IDRC. iv Acknowledgments We are grateful for the support and guidance of many people and the resources of different institutions, and in particular our respondents from the field, whose patience, encouragement and valuable insights were critical to our case study, both at the level of the research as well as analysis. Ms. Preeti Patkar and Mr. Prakash Reddy offered important information on the local and political history of Kamathipura that was critical in understanding the context of our site. Their deep knowledge of the neighbourhood and the rest of the city helped locate Kamathipura. We appreciate their insights of Mr. Sanjay Kadam, a long term resident of Siddharth Nagar, who provided rich history of the livelihoods and use of space, as well as the local political history of the neighbourhood. Ms. Nirmala Thakur, who has been working on building awareness among sex workers around sexual health and empowerment for over 15 years played a pivotal role in the research by facilitating entry inside brothels and arranging meetings with sex workers, managers and madams. -

Redharavi1.Pdf

Acknowledgements This document has emerged from a partnership of disparate groups of concerned individuals and organizations who have been engaged with the issue of exploring sustainable housing solutions in the city of Mumbai. The Kamala Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute of Architecture (KRVIA), which has compiled this document, contributed its professional expertise to a collaborative endeavour with Society for Promotion of Area Resource Centres (SPARC), an NGO involved with urban poverty. The discussion is an attempt to create a new language of sustainable urbanism and architecture for this metropolis. Thanks to the Dharavi Redevelopment Project (DRP) authorities for sharing all the drawings and information related to Dharavi. This project has been actively guided and supported by members of the National Slum Dwellers Federation (NSDF) and Dharavi Bachao Andolan: especially Jockin, John, Anand, Savita, Anjali, Raju Korde and residents’ associations who helped with on-site documentation and data collection, and also participated in the design process by giving regular inputs. The project has evolved in stages during which different teams of researchers have contributed. Researchers and professionals of KRVIA’s Design Cell who worked on the Dharavi Redevelopment Project were Deepti Talpade, Ninad Pandit and Namrata Kapoor, in the first phase; Aditya Sawant and Namrata Rao in the second phase; and Sujay Kumarji, Kairavi Dua and Bindi Vasavada in the third phase. Thanks to all of them. We express our gratitude to Sweden’s Royal University College of Fine Arts, Stockholm, (DHARAVI: Documenting Informalities ) and Kalpana Sharma (Rediscovering Dharavi ) as also Sundar Burra and Shirish Patel for permitting the use of their writings. -

Urban Biodiversity

NATIONAL BIODIVERSITY STRATEGY & ACTION PLAN – INDIA FOR MINISTRY OF ENVIRONEMENT & FORESTS, GOVERNMENT OF INDIA BY KALPAVRIKSH URBAN BIODIVERSITY By Prof. Ulhas Rane ‘Brindavan’, 227, Raj Mahal Vilas – II, First Main Road, Bangalore- 560094 Phone: 080 3417366, Telefax: 080 3417283 E-mail: < [email protected] >, < [email protected] > JANUARY 2003 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Nos. I. INTRODUCTION 4 II. URBANISATION: 8 1. Urban evolution 2. Urban biodiversity 3. Exploding cities of the world 4. Indian scenario 5. Development / environment conflict 6. Status of a few large Urban Centres in India III. BIODIVERSITY – AN INDICATOR OF A HEALTHY URBAN ENVIRONMENT: 17 IV. URBAN PLANNING – A BRIEF LOOK: 21 1. Policy planning 2. Planning authorities 3. Statutory authorities 4. Role of planners 5. Role of voluntary and non-governmental organisations V. STRATEGIC PLANNING OF A ‘NEW’ CITY EVOLVING AROUND URBAN BIODIVERSITY: 24 1. Introduction 2. General planning norms 3. National / regional / local level strategy 4. Basic principles for policy planning 5. Basic norms for implementation 6. Guidelines from the urban biodiversity angle 7. Conclusion VI. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 35 2 VII. ANNEXURES: 36 Annexure – 1: The 25 largest cities in the year 2000 37 Annexure – 2: A megalopolis – Mumbai (Case study – I) 38 Annexure – 3: Growing metropolis – Bangalore (Case study – II) 49 Annexure – 4: Other metro cities of India (General case study – III) 63 Annexure – 5: List of Voluntary & Non governmental Organisations in Mumbai & Bangalore 68 VIII. REFERENCES 69 3 I. INTRODUCTION About 50% of the world’s population now resides in cities. However, this proportion is projected to rise to 61% in the next 30 years (UN 1997a). -

FMA April 2016 Newsletter Cherie's Edit.Pages

Fletcher Maynard Academy Gazette FMA Visits India —Principal Harris In keeping with the Fletcher Maynard Academy tradition of international travel open to all students, friends, and faculty we travelled to Mumbai, FMA April Happenings Goa and Delhi in India during February vacation week in 2016. Meeting FMA parents Jonathan and Ulka Anjaria, who are on sabbatical in Mumbai • Friday, April 8 - Leadership Team Meeting, with their twins, 3rd grade boys, Rahaan and Naseem at the airport was a 8:30am treat. The third-graders who travelled with us were thrilled to be back in the company of the Anjaria boys. • Saturday, April 9 - Qualls Academy, 9am-12pm • Wednesday, April 13 - Parent/Teacher Mumbai has some very old buildings, and also many modern buildings Conferences along the shoreline. During our time in Mumbai we learned the word “slum” doesn’t always have a negative connotation. We visited the • Mon-Fri, April 18-22 - School Vacation Dharavi slum, which is one of the largest slums in the world. Dharavi has • Monday, April 25, PTO Meeting, 8:15 an active informal economy and community that exports goods such as • Tues-Thur, April 26-28, PARCC Assessment leather, pottery, and textiles all over the world. The people of Dharavi, a multi-religious, multi-ethnic diverse settlement, have pride in being part of Testing, Grades 3-5 generations that have lived there. A little like the pride of the “Area 4/ Port” residents of Cambridge. After three wonderful and hectic days in Mumbai, we had three relaxing days at the shore in Goa, and another three days in New Delhi and Old Delhi. -

Forced to the Fringes: Disasters of 'Resettlement' in India

REPORT FORCED TO 3 THE FRINGES Disasters of ‘Resettlement’ in India VASHI NAKA, MUMBAI YOUTH FOR UNITY AND VOLUNTARY ACTION Habitat International Coalition – South Asia Title and Suggested Citation Forced to the Fringes: Disasters of ‘Resettlement’ in India. Report Three: Vashi Naka, Mumbai. Housing and Land Rights Network (New Delhi: 2014) New Delhi, June 2014 ISBN: 978-81-902569-6-4 Research and Text Simpreet Singh Editor and Content Advisor Shivani Chaudhry Data Collection and Entry Dhanaraj Khare, Jagdish Patankar and Pooja Yadav Assistance Sitaram Shelar, Nabamalika Joardar and Farid Bhuyan Photographs Cover: Aravind Unni Inside: Anil Ingle, Aravind Unni and Jagdish Patnakar Design and Printing Aspire Design, New Delhi Published by Housing and Land Rights Network G-18/1 Nizamuddin West, Lower Ground Floor New Delhi – 110 013, INDIA +91-11-2435-8492 [email protected] / [email protected] www.hic-sarp.org In collaboration with Youth for Unity and Voluntary Action (YUVA) YUVA Centre Plot 23, Sector 7, Kharghar Navi Mumbai – 410 210 Maharashtra, INDIA Phone and Fax: +91-22-2774-0990/80/70 [email protected] www.yuvaindia.org Information presented in this report may be used for public interest purposes with appropriate citation and acknowledgement. This report is printed on CyclusPrint based on 100% recycled fi bres. FORCED TO THE FRINGES Disasters of ‘Resettlement’ in India REPORT THREE: VASHI NAKA, MUMBAI Contents List of Acronyms / Abbreviations iv Executive Summary v I. Introduction 1 II. Objectives and Methodology of the Study 3 III. Human Rights Framework 5 IV. Vashi Naka: The Site under Study 7 V. -

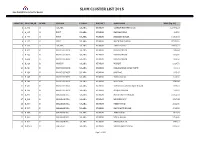

List of Slum Cluster 2015

SLUM CLUSTER LIST 2015 Slum Rehabilitation Authority, Mumbai OBJECTID CLUSTER_ID WARD VILLAGE TALUKA DISTRICT SLUM NAME AREA (Sq. M.) 1 A_001 A COLABA COLABA MUMBAI GANESH MURTHI NAGAR 120771.23 2 A_005 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI BANGALIPURA 318.50 3 A_006 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI NARIMAN NAGAR 14315.98 4 A_007 A FORT COLABA MUMBAI MACHIMAR NAGAR 37181.09 5 A_009 A COLABA COLABA MUMBAI GEETA NAGAR 26501.21 6 B_021 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 939.53 7 B_022 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 1292.90 8 B_023 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI DANA BANDAR 318.67 9 B_029 B MANDVI COLABA MUMBAI MANDVI 1324.71 10 B_034 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI NALABANDAR JOPAD PATTI 600.14 11 B_039 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI JHOPDAS 908.47 12 B_045 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI INDRA NAGAR 1026.09 13 B_046 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI MAZGAON 1541.46 14 B_047 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI SUBHASHCHANDRA BOSE NAGAR 848.16 15 B_049 B PRINCESS DOCK COLABA MUMBAI MASJID BANDAR 277.27 16 D_001 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI MATA PARVATI NAGAR 21352.02 17 D_003 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI BRANHDHARY 1597.88 18 D_006 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI PREM NAGAR 3211.09 19 D_007 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI NAVSHANTI NAGAR 4013.82 20 D_008 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI ASHA NAGAR 1899.04 21 D_009 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI SIMLA NAGAR 9706.69 22 D_010 D MALABAR HILL COLABA MUMBAI SHIVAJI NAGAR 1841.12 23 D_015A D GIRGAUM COLABA MUMBAI SIDHDHARTH NAGAR 2189.50 Page 1 of 101 SLUM CLUSTER LIST 2015 Slum Rehabilitation Authority, Mumbai OBJECTID CLUSTER_ID WARD VILLAGE TALUKA DISTRICT SLUM NAME AREA (Sq. -

Total List of MCGM and Private Facilities.Xlsx

MUNICIPAL CORPORATION OF GREATER MUMBAI MUNICIPAL DISPENSARIES SR SR WARD NAME OF THE MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY ADDRESS NO NO 1 1 COLABA MUNICIPALMUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 1ST FLOOR, COLOBA MARKET, LALA NIGAM ROAD, COLABA MUMBAI 400 005 SABOO SIDIQUE RD. MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY ( 2 2 SABU SIDDIQ ROAD, MUMBAI (UPGRADED) PALTAN RD.) 3 3 MARUTI LANE MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY MARUTI LANE,MUMBAI A 4 4 S B S ROAD. MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 308, SHAHID BHAGATSINGH MARG, FORT, MUMBAI - 1. 5 5 HEAD OFFICE MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY HEAD OFFICE BUILDING, 2ND FLOOR, ANNEX BUILDING, MUMBAI - 1, 6 6 HEAD OFFICE AYURVEDIC MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY HEAD OFFICE BUILDING, 2ND FLOOR, ANNEX BUILDING, MUMBAI - 1, 7 1 SVP RD. MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 259, SARDAR VALLABBHAI PATEL MARG, QUARTERS, A BLOCK, MAUJI RATHOD RD, NOOR BAUG, DONGRI, MUMBAI 400 8 2 WALPAKHADI MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 009 9B 3 JAIL RD. UNANI MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 259, SARDAR VALLABBHAI PATEL MARG, 10 4 KOLSA MOHALLA MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 20, KOLSA STREET, KOLSA MOHALLA UNANI , PAYDHUNI 11 5 JAIL RD MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY 20, KOLSA STREET, KOLSA MOHALLA UNANI , PAYDHUNI CHANDANWADI SCHOOL, GR.FLOOR,CHANDANWADI,76-SHRIKANT PALEKAR 12 1 CHANDAN WADI MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY MARG,MARINELINES,MUM-002 13 2 THAKURDWAR MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY THAKURDWAR NAKA,MARINELINES,MUM-002 C PANJRAPOLE HEALTH POST, RAMA GALLI,2ND CROSS LANE,DUNCAN ROAD 14 3 PANJRAPOLE MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY MUMBAI - 400004 15 4 DUNCAN RD. MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY DUNCAN ROAD, 2ND CROSS GULLY 16 5 GHOGARI MOHALLA MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY HAJI HASAN AHMED BAZAR MARG, GOGRI MOHOLLA 17 1 NANA CHOWK MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY NANA CHOWK, FIRE BRIGADE COMPOUND, BYCULLA 18 2 R. S. NIMKAR MUNICIPAL DISPENSARY R.S NIMKAR MARG, FORAS ROAD, 19 3 R. -

CONCEIVING the GODDESS an Old Woman Drawing a Picture of Durga-Mahishasuramardini on a Village Wall, Gujrat State, India

CONCEIVING THE GODDESS An old woman drawing a picture of Durga-Mahishasuramardini on a village wall, Gujrat State, India. Photo courtesy Jyoti Bhatt, Vadodara, India. CONCEIVING THE GODDESS TRANSFORMATION AND APPROPRIATION IN INDIC RELIGIONS Edited by Jayant Bhalchandra Bapat and Ian Mabbett Conceiving the Goddess: Transformation and Appropriation in Indic Religions © Copyright 2017 Copyright of this collection in its entirety belongs to the editors, Jayant Bhalchandra Bapat and Ian Mabbett. Copyright of the individual chapters belongs to the respective authors. All rights reserved. Apart from any uses permitted by Australia’s Copyright Act 1968, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the copyright owners. Inquiries should be directed to the publisher. Monash University Publishing Matheson Library and Information Services Building, 40 Exhibition Walk Monash University Clayton, Victoria 3800, Australia www.publishing.monash.edu Monash University Publishing brings to the world publications which advance the best traditions of humane and enlightened thought. Monash University Publishing titles pass through a rigorous process of independent peer review. www.publishing.monash.edu/books/cg-9781925377309.html Design: Les Thomas. Cover image: The Goddess Sonjai at Wai, Maharashtra State, India. Photograph: Jayant Bhalchandra Bapat. ISBN: 9781925377309 (paperback) ISBN: 9781925377316 (PDF) ISBN: 9781925377606 (ePub) The Monash Asia Series Conceiving the Goddess: Transformation and Appropriation in Indic Religions is published as part of the Monash Asia Series. The Monash Asia Series comprises works that make a significant contribution to our understanding of one or more Asian nations or regions. The individual works that make up this multi-disciplinary series are selected on the basis of their contemporary relevance.