BOM 08.12 Almanac Saison, Logsdon Seizoen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Suggested Topics for Homebrew Con 2021

Suggested Topics for Homebrew Con 2021 The suggestions below have been outlined by the Seminar Subcommittee for Homebrew Con 2021. The topics suggested are not intended to be an exhaustive list, but rather a guide to potential speakers to some of the top priority topics that the committee would like to see presented on at this year’s event. Hopeful speakers are welcome to submit proposals beyond the scope of these suggestions but are encouraged to keep them in mind when planning their proposal content. Beer Styles The BJCP recognizes over 130 distinct beer styles in its beer guidelines, along with countless others not in the guidelines. Each style has a unique history and characteristics and is brewed using specific brewing processes and techniques. The seminars in this track will highlight individual beer styles and the techniques used to brew them (and why). • How styles emerge (Ex: Kolsch/Alt, Regional International Ales [Argentina, Italian, New Zealand, Brazilian, etc.]) • Compare and contrast of similar styles • Differentiating general history from beer history • Emerging styles (Ex: pastry stouts/ fruit “slushies”, Winter Warmers, etc.) • How to decide where your beer goes in a competition • Saison • Bocks (history, sub-styles, brewing requirements, etc.) • How taxes, water chemistry, wars, technology and/or climate defined beer styles • Extinct (or nearly extinct) Styles • Historic beers (Ex: Stein Bier, Fraoch, Herbal, Wiccan ales, Egyptian ales) • Lager fundamentals • Best ways to educate yourself about a style - • Beer Vocabulary and what it all means ASBC (anyone?) • Belgian Styles (in general) – challenge to brew, make it taste like it’s from Belgium • How to brew authentic English Pub Ale • Fresh Hop Beers • Mead styles (Ex: Polish, historical meads, other) • How to achieve the style you are looking for (Expectations of what you want vs. -

Year of Saisons and Reflect Some of Smaller Brewers

s sure as this planet twirls around the sun, I know there is always a rea- son for a Saison. While brewers around me dabble with their Pale Ales, DIPAs and barleywines, I find myself thinking months ahead to Amy next funky farmhouse. My brewing calendar resembles the pages of The Old Farmer’s Almanac (Page 129, June 2008: “Brew a Saison Automné,” “Plow and Gun Combo Patented, 1862.”) My Saison epiphany came not from the farmlands of Wallonia, but from L.A.’s old- est (and now no longer brewing) brewpub, Crown City Brewing of Pasadena. Brewer Jay Baum dropped an unknown glass of beer in front of me and let the unusual smells confound my newbie nose. Some hops, some spice, a little malt and a whole wallop of weird opened my eyes to the existence of the style. Nights of studying every Saison I could find led to years of brewing with no end in sight for the experiment. A Tale of Two Breweries ton candy with crepes and every beer Saison comes in between 5 and 6.5 per- Founded in the mid 1800s, the Tourpes- from Dupont! cent abv to provide refreshment without based Brasserie Dupont stands as the dissolution. The super Saisons instead paragon of Saison brewers. Until the Matt shares responsibility for the Saison for sprawl across the spectrum in color, bitter- recent explosion of exploration, their Every Saison project because he took us to ness, spiciness and alcoholic power. Vieille Provision Saison was the single the crazy, scary wonderful world of Brewers use super Saisons for their wilder hallmark of the style. -

Saison: a Brewer's Blank Canvas

Saison: A Brewer’s Blank Canvas Presented by Peter (Pietro) Caira GTA Brews October General Meeting •10.16.2017 Bob’s Description: “I’ve never really thought of ‘saison’ as a style per say, but more of a school of brewing within the Belgian school. Regardless of their make-up, they should be What is Saison? aromatic, predominantly from the yeast as opposed to hops or malt. They should be dry and thirst quenching with a nice assertive hop presence at the end. Brett, a little light strike and that elusive cellar or musty like quality should be present in the best of them.” ~ Bob Sylvester - Saint Somewhere Brewing Co. Historically ... A low-alcohol “rustic” ale brewed during the harvest months in farmhouses across Wallonia What is Saison? for consumption by seasonal workers - “Saisonniers” - in the following summer months for refreshment while they work in the fields. Commercially ... One of the few (only?) styles of beer that can be called “farmhouse” that has been adopted (and adapted) by breweries for commercial What is Saison? production. As a result, the style is open to interpretation and has been used as a blank canvas by brewers everywhere to explore their creativity. Saison Style Guidelines Peter’s Guidelines BJCP Guidelines ● Dry, refreshing ● Category 25B ● Yeast-driven flavours & ● Allows for many variations aromas from esters including spiced and dark versions ● Well-balanced towards bitterness ● Three major strength levels: Table, Standard, ● Highly carbonated Super Saison Ingredients Grains, Adjuncts, Other Fermentables ● -

Full+Alcohol+List+8.30.17+Copy Copy

CRAFT BEERS Our Own Craft Beers are made here on-site. From the following list, we always have 6 beers on rotation. Please note the chalkboards which depict "What's on Tap" right now! Also, check the chalkboards for new and seasonal beers that haven't made this list. CREAM van BEAN Beer, Save the Queen Cream Ale, brewed with whole vanilla beans. Light, ESB English Ale, brewed with caramel malts and creamy and subtle vanilla flavor. 4.6% ABV. traditional hops. Sweet malt flavors are balanced by hop bitterness. 5.6% ABV LEGGY BLONDE Imperial Blonde Ale, deep blonde color, C4 big alcohol on the nose, sweet and malty, American Double IPA, brewed with multiple with a light hop character. Approx. 7% ABV. hop additions for complex citrus and tropical fruit flavors and lingering bitter finish. 7.5% ABV PASSIVE AGGRESSIVE PALE ALE , AKA "PAPA" Beach Front American Pale Ale, copper colored, a touch of White IPA, strong IPA with distinctive Belgian yeast and orange peel. Lots of orange flavor accentuated by caramel with aggressive hop character. 5.5% ABV. amarillo hops 8.3% ABV. "PAPA" Simcoe - variation with SIMCOE aroma UNKLE JOE'S FUNKY hops, piney and resinous DUNKLE WEISS "PAPA" Citra - variation with CITRA aroma hops, citrus and fruity hop character German-Style Dunkle Weiss, dark wheat beer, spicy, clove, banana, light caramel. 5% ABV. SMALL TOWN BROWN PROJECT "Y" Brown Ale, dark brown to almost black, toasty, chocolate, malt forward, smooth despite its dark color. Amber Ale, our harvest beer, dry-hopped with our Not Hoppy. -

Saison Target Statistics² Your Results Fermentables • 9 Lb German Pilsner Orig

Contact: Hours: 5401 Linda Vista Road, St 406 Mon-Thurs 10:00am - 10:00pm San Diego, CA 92110 Fri - Sun 9:00am - 10:00pm (619) 295-2337 [email protected] Cost $ $ $ $ $ Difficulty Saison Target Statistics² Your Results Fermentables • 9 lb German Pilsner Orig. Gravity: 1.065 • 0.5 lb Wheat Malt Final Gravity: 1.012 • 0.5 lb Bonlander Munich 10L • 1 lb Corn sugar (add at flame out) Est. % ABV: 6.9% Efficiency³: 70% Hop Additions This recipe recommends a 90 min boil due to the presence of IBUs: 31 Pilsner malt. Begin adding hops at 60 min. • 60 min: 2 oz Hallertaur (4.5% AA¹) BJCP Style Guidelines: Saison (25B) • Flame Out: 2 oz Hallertaur (4.5% AA) Original Gravity: 1.048 – 1.065 SG Final Gravity: 1.002 – 1.008 SG Yeast • WLP 565: Belgian Saison I Ale Yeast Bitterness: 20 – 35 IBUs Ideal fermentation temperature: 68-75F ABV: 3.5 – 9.5% Overall Impression: Originally a rustic, Additives artisanal ale made with local, farm- • Clarifier: 1 tsp Irish Moss or 1 tablet produced ingredients, it is now brewed Whirlfloc mostly in larger breweries yet retains the image of its humble origins. At standard • Yeast Nutrient: ½ tsp White Labs (½ strengths and pale color, similar to a more tsp/gal Biotin) highly-attenuated, hoppy, and bitter Belgian blond ale with a stronger yeast character. Notes: Tricks of the Trade: Saison ale yeasts sometimes struggle to attenuate. To get the classic dry finish expected in a Saison, bring the fermentation temperature up to 80F after 4 days 1AA (Alpha Acid): This is the measure of hops’ potential bitterness. -

A Saison for Every Season – the Web Version the Story

Exploration of Saison, Yeasts and a Rant on the meaning of “Farmhouse” A SAISON FOR EVERY SEASON – THE WEB VERSION THE STORY Romance Fields of Grain Thirsty Farm hands Combine them together and what do you get? Saison WHAT’S THE REAL STORY “In Belgium there are no styles” - Peter Bouckaert The Romantic Story courtesy of brewers (via Michael Jackson) Liège – in text - 1900’s – oats, buckwheat, spelt. No mention by Jean De Clerck. The Saison is a 20th century amalgamation of tradition WHAT MAKES A SAISON SAISON Is it really the BJCP Dupontish model? You know the drill – orange colored, rocky head, spicy, fruit aromas with a dash of hops How do we reconcile: Dupont Vielle Provision Dupont Avec Les Bon Voeux Fantome Pissenlit Fantome Automne First person to say “Belgian Specialty” gets a kick to the knee. WHAT SAISON IS NOT A heavily spiced beer that reeks of coriander and oranges. Cloyingly, clingly sweet Brett is not an excuse for these flavor Flat Acetic Sour WHAT MAKES A SAISON – DREW’S MANIFESTO Dry We’ll leave the sweetness to the Abbey Earthy Needs that grounding middle malt and “dirt” Spicy Want spicy tones (eugenol, etc) – better if from the yeast Lively CO2 and acidity. Tart? Only as a secondary characteristic. Yeast Driven THE EXPERIMENT Gather together as many different Saison strains as possible Brew a simple wort Pitch simply (and fresh) Ferment the same (with exceptions) Brewing by Eagle Rock Brewery YEAST ON PARADE Kindly provided by the fine folks of White Labs, Wyeast, East Coast Yeast Company and the Bruery. -

Release Calendar 2021NEW(1A)

2021 WHOLESALE RELEASE CALENDAR Availability: 500mL bottles & 20L one way kegs through your Ninkasi Rep BOURBON BARREL AGED FEB MAY AUG NOV Maestro Barleywine Rhino Suit Imperial milk stout Coconut Rhino Suit Imperial milk stout with coconut SOUR & WILD BARREL AGED Kriek Sour ale with cherries Stonefruit Symphony Sour ale with nectarines & peaches Valley Preserves Sour ale with boysenberries, blueberries & cherries Cherry Parliament Flanders red ale with cherries Touch of Brett Dry-hopped French-style saison Award winning barrel-aged beer, handcrafted in Oregon’s Willamette Valley • www.alesongbrewing.com 2021 WHOLESALE RELEASE CALENDAR - Available through your Ninkasi Rep - BOURBON BARREL AGED BEERS Barleywine ales have often been considered the dean of beer styles, and our Maestro Maestro is no exception. Aged in freshly emptied Heaven Hill bourbon barrels, Barleywine this oak-forward leader crescendos from first sip to last. Toffee, vanilla, and MARCH RELEASE spice aromas lead the band and a balanced sweet, caramel-like malt flavor rounds out this full bodied ale. Rhino Suit was the first spirits-barrel-aged beer we released and remains one Rhino Suit of our favorites. Our imperial milk stout is matured in a blend of freshly emp- Imperial milk stout tied bourbon barrels adding velvety aromas of vanilla, coconut and oak, layerd NOVEMBER RELEASE atop the sweet and chocolatey malt flavors of the base beer. Bronze, Oregon Beer awards 2017, “Barrel Aged” category We aged our rich and chocolatey imperial milk stout in freshly emptied Coconut Heaven Hill barrels to add flavors of vanilla and coconut and sweet bour- Rhino Suit bon-like notes. -

Featured Cask

BOTTLED BEER BELGIUM UNITED STATES Chimay Cinq Cents, Tripel (white btl) 8.0 $15 Chimay Grande Reserve, Strong Ale (blue btl) 9.0 $15 Allagash Belfius, Saison Ale blended w/ spontaneoulsy 6.7 $30 fermented ale Chimay Premiere, Dubbel (red btl) 7.0 $15 179 Crown Street New Haven, CT 06510 Allagash Coolship Resurgam, spontaneously fermented 6.4 $30 Brouwerij Verhaeghe Douchesse Chocolate Cherry, ale aged in oak barrels Flanders Red Ale 6.8 $25 (475) 238-8335 Allagash Ganache, Dark Ale Fermented w/ Brettanomyces & 7.5 $30 Delirium Nocturnum, Belgian Strong Dark Ale 8.5 $25 aged on Raspberries Delirium Red, Belgian Ale w/ Cherry & Elderberry 8.0 $25 -FEATURED CASK- Almanac Astounding Enterprises, Imperial Sour Red Ale 9.2 $25 aged in Wine Barrels Delirium Tremens, Belgian Ale 8.5 $14 SINGLECUT DIAMOND STAR HALO Almanac Cherry Berry, Imperial Sour Red Ale aged in Wine Belgian Pale Ale 6.2 $14 Barrels w/ Cherries, Raspberries, Blackberries & 7.4 $25 Orval Trappist Ale, INDIA PALE ALE Vanilla Bean Tilquin Gueuze, Lambic Ale (Belgium) 7.0 $45 DOUBLE DRY HOPPED W/ GALAXY Almanac Strawberry & Basil, Sour Farmhouse Ale aged in Oak 6.5 $25 Barrels w/ Strawberries, Basil & Spices Trappistes Rochefort 6, Dubbel (Belgium) 7.5 $12 Trappistes Rochefort 8, Belgian Strong Dark Ale 9.2 $14 OZ Almanac Tropical Galaxy, American Wild Ale aged on Pineapples, 6.4 $25 6.6% | 12 | $8 Mangoes, Lime & Coconuts & Dry-Hopped w/ Galaxy Hops Trappistes Rochefort 10, Quadruple 11.3 $16 Brooklyn Local #1, Belgian Strong Ale 9.0 $19 Brooklyn Local #2, Belgian Strong Dark -

Beer Bottles

Aslan Brewing Co. STYLE ABV SIZE PRICE Frances Farmer 2019 Foeder-Aged Brett Saison 6.3% 500mL $10.00 3 deep (2021) Blend of Oak-Aged Beers for Our Third Anniversary 5.8% 500mL $14.00 oud bruin Flanders-style Brown Ale 7.0% 500mL $12.00 Confluence Blended Saison in Collaboration w/ Wander Brewing 7.0% 500mL 13.00 Strawberry Dojo 2020 Saison Aged on Raspberries 6.2% 500mL 14.00 Frances Farmer 2016 Wine Barrel-Aged Saison 6.3% 500mL 22.00 Frances Farmer 2018 Foeder-Aged Saison 6.3% 500mL 20.00 1 international BREWERY BEER ABV STYLE SIZE PRICE Belgium Blaugies Saison D’Épeautre 6.0% Spelt Saison 375mL $9.50 Boon Schaarbeekse Kriek Lambic 6.5% Lambic w/ Schaarbeekse Cherries 375mL $10.50 De La Senne Ouden Vat 6.7% Flanders Red 331mL $8.00 De La Senne/ Schieve Saison 2018 5.2% Oak Aged Saison 375mL $6.50 Crooked Stave De Ranke Cuvée de Ranke 2017 7.0% Blended Oak Aged Ale 750mL $21.50 Dupont Dry Hopping 6.5% Dry-Hopped Saison 750mL $16.00 Dupont Saison Dupont 6.5% Saison 750mL $13.75 Duvel Moortgat Duvel 8.5% Belgian Strong Golden 330mL $6.00 Hanssen’s Oude Gueuze 6.0% Gueuze 375mL $12.00 Hanssen’s Oude Kriek 6.0% Oude Kriek 750mL $16.00 Hof ten Dormaal Sloe 6.5% Wild Ale w/ Sloe Berries 331mL $10.40 Lindeman’s Cuvee Rene 5.2% Gueuze 375mL $9.00 Lindeman’s Ginger Gueuze 6.0% Lambic w/ Ginger 750mL $30.50 Lindemans Kriek Lambic 3.7% Lambic w/ Fruit 750mL $12.00 Mikkeller Spontan Nelson 7.3% Dry-hopped Wild Ale 750mL $28.99 Orval Oude Orval 3/1/17 6.2% Trappist Pale 331mL $7.25 Orval Oude Orval 3/19/18 6.2% Trappist Pale 331mL $7.25 Orval Oude -

Amber/Brown Stout/Porter White/Wheat/Blonde Saison/Sour

LOCAL BREWS ON TAP Red Clay Halftime Hefeweisen Opelika, AL 5.6%ABV $7 Good People Snakehandler Double IPA Birmingham, AL 10.0%ABV $9 Back Forty Truck Stop Honey Brown Gadsden, Al 6.0%ABV $7 IPA Amber/Brown Wild Leap Chance IPA Lagrange, GA 6.5%ABV $5 Elysian Space Dust $4 New Belgium Fat Tire $4 Wild Leap Alpha 11 Double IPA Lagrange, GA 5.0%ABV $6 Trimtab IPA $4 Against the Grain The Brown Note 16oz $7 Ferus Country Lager Lager Trussville, AL 7.8%ABV $8 Sixpoint Hootie IPA 16oz $9 Oyster City Hooter Brown $4 Red Clay Sweet Tea Ale Ale Opelika, AL 5.0%ABV $7 Heretic Make America Juicy Again $6 Common Bond Blonde Blonde Ale Montgomery, AL 5.2%ABV $6 Scofflaw Basement IPA $4 Wild Leap Three Harvest Double IPA Lagrange, GA 8.2%ABV $5 Stout/Porter Elysian Contact Haze $4 Wild Leap The 13th Double IPA Lagrange, GA 8.0%ABV $8 DuClaw Sweet Baby Jesus $5 Wild Leap Time, Love, and Tenderness $7 Goat Island Blood Orange Berliner Weisse Cullman, AL 5.0%ABV $7 Evil Twin Imperial Wedding Cake 16oz $18 Wild Leap Lemon Ice Double IPA $7 Pretoria Fields Walkers Station $4 Orpheus Elusory IPA $7 Cross Eyed Owl One Shoe Brown $4 Good People Hitchhiker IPA $5 Wild Leap Rocky Road Ice Cream Stout $7 Blackberry Farms Farm Roots Run Deep $5 Kentucky Bourbon Ale Lexington, KY 8.0%ABV $7 Wild Leap Three Harvest Fresh Hop $5 DuClaw For Pete’s Sake Imperial Porter Baltimore, MD 9.0%ABV $8 Monday Night Blind Pirate $4 White/Wheat/Blonde Prairie Pineapple Upside Down Cake Sour Ale Tulsa, OK 4.9%ABV $7 Cahaba Blonde $4 Prairie Rainbow Sherbet Sour Ale Tulsa, OK -

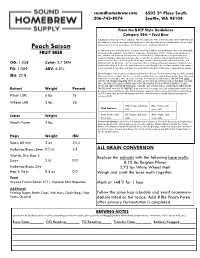

Peach Saison the Beer Based on the Pleasantness and Balance of the Resulting Combination

th soundhomebrew.com 6505 5 Place South 206-743-8074 Seattle, WA 98108 From the BJCP Style Guidelines Category 29A – Fruit Beer A harmonious marriage of fruit and beer. The key attributes of the underlying style will be different with the addition of fruit; do not expect the base beer to taste the same as the unadulterated version. Judge Peach Saison the beer based on the pleasantness and balance of the resulting combination. As with aroma, the distinctive flavor character associated with the particular fruit(s) should be noticeable, FRUIT BEER and may range in intensity from subtle to aggressive. The balance of fruit with the underlying beer is vital, and the fruit character should not be so artificial and/or inappropriately overpowering as to suggest a fruit juice drink. Hop bitterness, flavor, malt flavors, alcohol content, and fermentation by- products, such as esters or diacetyl, should be appropriate to the base beer and be harmonious and OG: 1.058 Color: 3.7 SRM balanced with the distinctive fruit flavors present. Note that these components (especially hops) may be intentionally subdued to allow the fruit character to come through in the final presentation. Some tartness may be present if naturally occurring in the particular fruit(s), but should not be inappropriately intense. FG: 1.009 ABV: 6.5% Overall balance is the key to presenting a well-made fruit beer. The fruit should complement the original IBU: 27.8 style and not overwhelm it. The brewer should recognize that some combinations of base beer styles and fruits work well together while others do not make for harmonious combinations. -

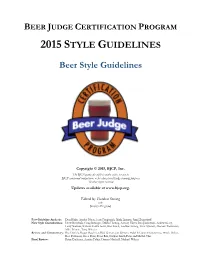

2015 BJCP Beer Style Guidelines

BEER JUDGE CERTIFICATION PROGRAM 2015 STYLE GUIDELINES Beer Style Guidelines Copyright © 2015, BJCP, Inc. The BJCP grants the right to make copies for use in BJCP-sanctioned competitions or for educational/judge training purposes. All other rights reserved. Updates available at www.bjcp.org. Edited by Gordon Strong with Kristen England Past Guideline Analysis: Don Blake, Agatha Feltus, Tom Fitzpatrick, Mark Linsner, Jamil Zainasheff New Style Contributions: Drew Beechum, Craig Belanger, Dibbs Harting, Antony Hayes, Ben Jankowski, Andew Korty, Larry Nadeau, William Shawn Scott, Ron Smith, Lachlan Strong, Peter Symons, Michael Tonsmeire, Mike Winnie, Tony Wheeler Review and Commentary: Ray Daniels, Roger Deschner, Rick Garvin, Jan Grmela, Bob Hall, Stan Hieronymus, Marek Mahut, Ron Pattinson, Steve Piatz, Evan Rail, Nathan Smith,Petra and Michal Vřes Final Review: Brian Eichhorn, Agatha Feltus, Dennis Mitchell, Michael Wilcox TABLE OF CONTENTS 5B. Kölsch ...................................................................... 8 INTRODUCTION TO THE 2015 GUIDELINES............................. IV 5C. German Helles Exportbier ...................................... 9 Styles and Categories .................................................... iv 5D. German Pils ............................................................ 9 Naming of Styles and Categories ................................. iv Using the Style Guidelines ............................................ v 6. AMBER MALTY EUROPEAN LAGER .................................... 10 Format of a