The Grand Circularity of Woman's Building Video

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Provoking Change Mandeville Art Center Art Mandeville UC San Diego a Visual Arts Alumni Exhibition 12 – December 9, 2017 October Art Gallery University

Provoking Change Provoking A Visual Arts Alumni Exhibition October 12 – December 9, 2017 University Art Gallery Mandeville Art Center UC San Diego Provoking Change VA 50 Provoking Change David Avalos Doris Bittar Becky Cohen Joyce Cutler-Shaw Brian Dick Kip Fulbeck Heidi Hardin Robert Kushner Hung Liu Fred Lonidier Jean Lowe Kim MacConnel Susan Mogul Allan Sekula Elizabeth Sisco/Louis Hock/David Avalos Deborah Small/David Avalos Introduction Exploring a segment of the and Robert Kushner challenged the unique early history of the Visual conventional idea of painting as a Arts Department, Provoking Change two-dimensional work on canvas. celebrates an extraordinary roster Executed as a kind of cloth hanging, of artists who came to study in San both MacConnel’s Turkish Delight Diego in the early 1970s through the and Kushner’s Big Blue Chador 1990s. Diverse in their approaches, question the long-standing pejorative these artists shared a desire to foster dismissal of decoration. change by challenging the narrow- Hung Liu’s Five Star Red Flag ly defined avant-garde canon as and German Shepherd, on the other manifested in the formalism of the hand, are a significant contribu- 1960s. In contrast to the influential tion to the revival of traditions of American critic Clement Greenberg, avant-garde painting in China. After who considered political art rene- arriving to UCSD, Liu mastered gade and aesthetically inferior to the layered brushstrokes and drippy avant-garde, UC San Diego artists appearance of paint in her work that made art that introduced multi-cul- serve as a visual metaphor for the tural voices, pointed out women’s loss of historical memory. -

Protest » Video- Collage

FemLink, the International Videos-Collage LIST OF VIDEOS in THE « PROTEST » VIDEO- COLLAGE 26 videos - 50 min. The videos inccluded in the collage was created for FemLink 01 - IT’S JUST A GAME, Maria Rosa Jijon (Ecuador) The word Game is indeed a trap: not only translates into play but, above all, in prey. In an era apparently facilitated by the invasion of computers and machines, the reality is that everything looks, more and more, like the locations of Orwell’s 1984. The removal of spatio- temporal boundaries is just a consolation prize, because the customs continue to exist and overcome them is always crooked at least as to live as emigrants once exceeded. Ilaria Giordano Drome Magazine CREDITS : Music: Mario Bross 02 - OVERFLOW. A NOTE OF SUICIDE, Sara Malinarich (Chile) A woman sacrifices herself in a technological scene, in front of virtual witnesses and streets coexisting in time in different places. The screen is the suicide note, the physical support of a protest that overflows through an invisible mechanics that activates the self-destruction sequence. It is the suicide note that burns and sets fire to the woman, becoming the bonfire of her protests. 'Overflow' is a videocreation made in real-time with automated machines and telepresence systems (and a veiled tribute to José Val del Omar.) Credits: Cast: CAROLINA PRIEGO. Technical Management: MANUEL TERÁN. Photography: MAKU LÓPEZ. Edition, Postproduction & Graphics: JORGE RUIZ ABÁNADES. 3D Motion: FRANÇOIS MOURRE. Music: EN BUSCA DEL PASTO Note: The audio of this piece is in Dia-phonic system, created by José Val del Omar in 1944. -

High Performance Magazine Records

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt5p30369v Online items available Finding aid for the magazine records, 1953-2005 Finding aid for the magazine 2006.M.8 1 records, 1953-2005 Descriptive Summary Title: High Performance magazine records Date (inclusive): 1953-2005 Number: 2006.M.8 Creator/Collector: High Performance Physical Description: 216.1 Linear Feet(318 boxes, 29 flatfile folders, 1 roll) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: High Performance magazine records document the publication's content, editorial process and administrative history during its quarterly run from 1978-1997. Founded as a magazine covering performance art, the publication gradually shifted editorial focus first to include all new and experimental art, and then to activism and community-based art. Due to its extensive compilation of artist files, the archive provides comprehensive documentation of the progressive art world from the late 1970s to the late 1990s. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical/Historical Note Linda Burnham, a public relations officer at University of California, Irvine, borrowed $2,000 from the university credit union in 1977, and in a move she described as "impulsive," started High -

Oral History Interview with Suzanne Lacy, 1990 Mar. 16-Sept. 27

Oral history interview with Suzanne Lacy, 1990 Mar. 16-Sept. 27 Funding for the digital preservation of this interview was provided by a grant from the Save America's Treasures Program of the National Park Service. Contact Information Reference Department Archives of American Art Smithsonian Institution Washington. D.C. 20560 www.aaa.si.edu/askus Transcript Preface The following oral history transcript is the result of a tape-recorded interview with Suzanne Lacy on March 16, 1990. The interview took place in Berkeley, California, and was conducted by Moira Roth for the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. This interview has been extensively edited for clarification by the artist, resulting in a document that departs significantly from the tape recording, but that results in a far more usable document than the original transcript. —Ed. Interview [ Tape 1, side A (30-minute tape sides)] MOIRA ROTH: March 16, 1990, Suzanne Lacy, interviewed by Moira Roth, Berkeley, California, for the Archives of American Art. Could we begin with your birth in Fresno? SUZANNE LACY: We could, except I wasn’t born in Fresno. [laughs] I was born in Wasco, California. Wasco is a farming community near Bakersfield in the San Joaquin Valley. There were about six thousand people in town. I was born in 1945 at the close of the war. My father [Larry Lacy—SL], who was in the military, came home about nine months after I was born. My brother was born two years after, and then fifteen years later I had a sister— one of those “accidental” midlife births. -

Partial Artist List: Nancy Angelo Jerri Allyn Leslie Belt Rita Mae Brown Kathleen Burg Elizabeth Canelake Velene Campbell Carol Chen Judy Chicago Clsuf Michelle T

Doin’ It in Public: Feminism and Art at the Woman’s Building October 1, 2011 – January 28, 2012 Ben Maltz Gallery, Otis College of Art and Design This exhibition presents artwork, graphic design, ephemera, and documentation of work by the artist collectives and individual artists/designers who participated in collaborative projects at the Woman’s Building in Los Angeles between 1973-1991. Artist Collectives/Projects: Ariadne: A Social Network, Feminist Art Workers, Incest Awareness Project, Lesbian Art Project, Mother Art, Natalie Barney Collective, Sisters of Survival, The Waitresses, Chrysalis: A magazine of Women’s Culture, and more. Partial artist list: Nancy Angelo Jerri Allyn Leslie Belt Rita Mae Brown Kathleen Burg Elizabeth Canelake Velene Campbell Carol Chen Judy Chicago Clsuf Michelle T. Clinton Hyunsook Cho Yreina Cervantez Candace Compton Jan Cook Juanita Cynthia Sheila Levrant de Bretteville Johanna Demetrakas Nelvatha Dunbar Mary Beth Edelson Marguerite Elliot Donna Farnsworth Anne Finger Audrey Flack As of 9-27-11 Amani Fliers Nancy Fried Patricia Gaines Josephina Gallardo Diane Gamboa Cristina Gannon Anne Gauldin Cheri Gaulke Anita Green Vanalyne Green Mary Bruns Gonenthal Kirsten Grimstad Chutney Gunderson Berry Brook Hallock Hella Hammid Harmony Hammond Gloria Hajduk Eloise Klein Healy Mary Linn Hughes Annette Hunt Sharon Immergluck Ruth E. Iskin Cyndi Kahn Maria Karras Susan E. King Laurel Klick Deborah Krall Christie Kruse Sheila Levrant de Bretteville Suzanne Lacy Leslie Labowitz-Starus Lili Lakich Linda Lopez Bia -

Before Projection: Video Sculpture 1974–1995 Contents

Henriette Huldisch Before Projection: Video Sculpture 1974–1995 Contents 5 Director’s Foreword 9 Acknowledgments 13 Before and Besides Projection: Notes on Video Sculpture, 1974–1995 Henriette Huldisch Artist Entries Emily Watlington 57 Dara Birnbaum 81 Tony Oursler 61 Ernst Caramelle 85 Nam June Paik 65 Takahiko Iimura 89 Friederike Pezold 69 Shigeko Kubota 93 Adrian Piper 73 Mary Lucier 97 Diana Thater 77 Muntadas 101 Maria Vedder 121 Time Turned into Space: Some Aspects of Video Sculpture Edith Decker-Phillips 135 List of Works 138 Contributors 140 Lenders to the Exhibition 141 MIT List Visual Arts Center 5 Director’s Foreword It is not news that today screens occupy a vast amount of our time. Nor is it news that screens have not always been so pervasive. Some readers will remember a time when screens did not accompany our every move, while others were literally greeted with the flash of a digital cam- era at the moment they were born. Before Projection: Video Sculpture 1974–1995 showcases a generation of artists who engaged with monitors as sculptural objects before they were replaced by video projectors in the gallery and long before we carried them in our pockets. Curator Henriette Huldisch has brought together works by Dara Birnbaum, Ernst Caramelle, Takahiko Iimura, Shigeko Kubota, Mary Lucier, Muntadas, Tony Oursler, Nam June Paik, Friederike Pezold, Adrian Piper, Diana Thater, and Maria Vedder to consider the ways in which artists have used the monitor conceptually and aesthetically. Despite their innovative experimentation and per- sistent relevance, many of the sculptures in this exhibition have not been seen for some time—take, for example, Shigeko Kubota’s River (1979–81), which was part of the 1983 Whitney Biennial but has been in storage for decades. -

Nancy Buchanan Consumption

NANCY BUCHANAN CONSUMPTION ).'82/+0'3+9-'22+8? NANCY BUCHANAN CONSUMPTION Charlie James Gallery is delighted to present Consumption, Buchanan has collaborated with Carolyn Potter to make our first solo show with Los Angeles-based artist Nancy miniatures incorporating video. In American Dream #6, Buchanan. their very first piece together, every surface is littered with home improvement brochures while on the small TV Joe Intending to focus on painting at UC Irvine, Nancy McCarthy is shouting, and bundled newspapers trace the Buchanan’s (b. 1946, Boston, MA) conceptual bent started history of atomic weapons. Another miniature – Use Value when she was a student of Robert Irwin. Absorbing his celebrates the local economies of garage sales. lesson that art is an experience rather than an object, she extended her production to unusual materials (shredded Buchanan will donate 50% of the proceeds of her sales from newspaper, human hair) and methods of presentation. the 50 Shades of Cake series to the LAMP organization Buchanan works across drawing, performance, video, collage, (begun in 1985 as Los Angeles Men’s Place) that assists mixed media work and installation. As she embraces the homeless people in and around Skid Row. notion that art should evidence the time of its making, Buchanan’s pieces often address social and political Beginning with her participation as a founding member of issues. F Space Gallery in Costa Mesa, Nancy Buchanan has been involved in numerous artists’ groups including The Los “Consumption” was the 19th-century name for tuberculosis, Angeles Woman’s Building and Los Angeles Contemporary from the Latin root con (completely) plus sumere (to take Exhibitions (LACE); she has also acted as curator for up from under), a disease Buchanan suffered from as a young several exhibitions and projects. -

25 Years of Ars Electronica

Literature: Winners in the film section – Computer Animation – Visual Effects Literature: Literature : Literature: Literature (2) : Literature: Literature (2) : Blick, Stimme und (k)ein Körper – Der Einsatz 1987: John Lasseter, Mario Canali, Rolf Herken Cyber Society – Mythos und Realität der Maschinen, Medien, Performances – Theater an Future cinema !! / Jeffrey Shaw, Peter Weibel Ed. Gary Hill / Selected Works Soundcultures – Über elektronische und digitale Kunst als Sendung – Von der Telegrafie zum der elektronischen Medien im Theater und in 1988: John Lasseter, Peter Weibel, Mario Canali and Honorary Mentions (right) Informationsgesellschaft / Achim Bühl der Schnittstelle zu digitalen Welten / Kunst und Video / Bettina Gruber, Maria Vedder Intermedialität – Das System Peter Greenaway Musik / Ed. Marcus S. Kleiner, A. Szepanski 25 years of ars electronica Internet / Dieter Daniels VideoKunst / Gerda Lampalzer interaktiven Installationen / Mona Sarkis Tausend Welten – Die Auflösung der Gesellschaft Martina Leeker (Ed.) Yvonne Spielmann Resonanzen – Aspekte der Klangkunst / 1989: Joan Staveley, Amkraut & Girard, Simon Wachsmuth, Zdzislaw Pokutycki, Flavia Alman, Mario Canali, Interferenzen IV (on radio art) Liveness / Philip Auslander im digitalen Zeitalter / Uwe Jean Heuser Perform or else – from discipline to performance Videokunst in Deutschland 1963 – 1982 Arquitecturanimación / F. Massad, A.G. Yeste Ed. Bernd Schulz John Lasseter, Peter Conn, Eihachiro Nakamae, Edward Zajec, Franc Curk, Jasdan Joerges, Xavier Nicolas, TRANSIT #2 -

Barbara T. Smith Coffin Series and Related Material, 1965-1967

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8st7rjv Online items available Finding aid for the Barbara T. Smith Coffin series and related material, 1965-1967 Isabella Zuralski Finding aid for the Barbara T. 2013.M.23 1 Smith Coffin series and related material, 1965-1967 Descriptive Summary Title: Barbara T. Smith Coffin series and related material Date (inclusive): 1965-1967 Number: 2013.M.23 Creator/Collector: Smith, Barbara Turner, 1931- Physical Description: 12.26 Linear Feet(16 boxes) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: The collection comprises Coffin, a unique set of twenty-five hand-bound artist's books documenting Barbara T. Smith's experiments with an early Xerox 914 copy machine, and a set of working materials and other works related to the Coffin series. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English. Biographical / Historical Note Barbara T. Smith, a pioneer in performance and body art, was born in Pasadena, California in 1931. She studied painting, art history and religion at Pomona College, graduating in 1953. In 1965, she began to study at the Chouinard Art Institute in Los Angeles, and in 1971, she received her MFA from the University of California, Irvine. While attending UC Irvine, she founded, together with Nancy Buchanan and Chris Burden, the student-run experimental art gallery F-Space. -

A Performing Archive 17.02.17, 10�14

re.act.feminism - a performing archive 17.02.17, 1014 Search A Ebtisam Abdulaziz Marina Abramović Helena Almeida Eleanor Antin Arahmaiani Malin Arnell Oreet Ashery Augusta Atla Margarita Azurdia B Back to selection Antonia Baehr Complete Archive Maja Bajević Manon, La dame au crâne rasé, 1970s Anne Bean Anat Ben-David Renate Bertlmann Manon Document media Pauline Boudry & Das lachsfarbene Boudoir / La dame au crâne video, colour, sound, 12:10 min Renate Lorenz rasé Issue date Nisrine Boukhari 1974, 1978 / 2006 After studying commercial art and acting in Zurich, in 1974 Marijs Boulogne Tags Manon (*1946, Switzerland) began creating environments in Tania Bruguera beauty, fashion/glamour, which she plays different roles together with sometimes as femininity, in/visibility, Nancy Buchanan many as 60 extras and uses virtually all forms of modern private/public Maris Bustamante media. She was one of Switzerland’s first performance artists About the project C Archive Signature Partners and is most likely the country’s most famous. She lived in Paris MAN 1 Cabello / Carceller Imprint from 1977 to 1980 before moving back to Zurich, where she lives Shirley Cameron/ Contact and works today. Since 1998, she has been concentrating Monica Ross/ Find us on facebook mainly on installations which explore eroticism and transience, Evelyn Silver most recently in 2011 in her project "Hotel Dolores" concerned Graciela Carnevale with deserted spa hotels in the spa district of Baden, Aargau Theresa Hak Kyung (Switzerland). Cha Helen Chadwick This is a collection of TV features about, among other works, Manon’s Das lachsfarbene Boudoir (The Salmon-Coloured Chicks on Speed Boudoir), her first environment which she reconstructed for the Lygia Clark Migros Museum Zurich in 2006, and La dame au crâne rasé (The Mary Coble Woman with the Shaved Head), a series of staged photographs Colette in Paris. -

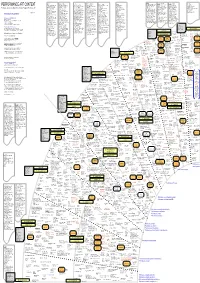

Performance Art Context R

Literature: Literature: (...continued) Literature: Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Literature: (... continued) Literature: Kunstf. Bd.137 / Atlas der Künstlerreisen Literature: (...continued) Literature: (... continued) Richard Kostelnatz / The Theater of Crossings (catalogue) E. Jappe / Performance Ritual Prozeß Walking through society (yearbook) ! Judith Butler !! / Bodies That Matter Victoria Best & Peter Collier (Ed.) / article: Kultur als Handlung Kunstf. Bd.136 / Ästhetik des Reisens Butoh – Die Rebellion des Körpers PERFORMANCE ART CONTEXT R. Shusterman / Kunst leben – Die Ästhetik Mixed Means. An Introduction to Zeitspielräume. Performance Musik On Ritual (Performance Research) Eugenio Barber (anthropological view) Performative Acts and Gender Constitution Powerful Bodies – Performance in French Gertrude Koch Zeit – Die vierte Dimension in der (Kazuo Ohno, Carlotta Ikeda, Tatsumi des Pragmatismus Happenings, Kinetic Environments ... ! Ästhetik / Daniel Charles Richard Schechner / Future of Ritual Camille Camillieri (athropolog. view; (article 1988!) / Judith Butler Cultural Studies !! Mieke Bal (lecture) / Performance and Mary Ann Doane / Film and the bildenden Kunst Hijikata, Min Tanaka, Anzu Furukawa, Performative Approaches in Art and Science Using the Example of "Performance Art" R. Koberg / Die Kunst des Gehens Mitsutaka Ishi, Testuro Tamura, Musical Performance (book) Stan Godlovitch Kunstforum Bd. 34 / Plastik als important for Patrice Pavis) Performativity and Performance (book) ! Geoffrey Leech / Principles -

Abstract Suzanne Lacy

ABSTRACT SUZANNE LACY: THREE WEEKS IN MAY Suzanne Lacy’s continuous involvement in both the feminist and anti-rape movements during the 1970s helped raise social awareness on the subject of rape, an issue that was rarely taken seriously and often misunderstood. Beginning with a brief outline of the anti-rape movement and its feminist context, this paper will explore Lacy’s groundbreaking work, Three Weeks in May, a Los Angeles based event that addressed the issue of rape using a combination of art and social organization. This three week long event consisted of gallery installations, self- defense demonstrations, public speak-outs and street performances. In this thesis I will take into consideration the benefits of utilizing public art as a means to address social and political issues, and elucidate Three Weeks in May’s contribution to the anti-rape movement. Emily Louise Krause May 2010 SUZANNE LACY: THREE WEEKS IN MAY by Emily Louise Krause A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art in the College of Arts and Humanities California State University, Fresno May 2010 © 2010 Emily Louise Krause APPROVED For the Department of Art and Design: We, the undersigned, certify that the thesis of the following student meets the required standards of scholarship, format, and style of the university and the student's graduate degree program for the awarding of the master's degree. Emily Louise Krause Thesis Author Keith Jordan (Chair) Art and Design Laura Meyer Art and Design Nancy Youdelman Art and Design For the University Graduate Committee: Dean, Division of Graduate Studies AUTHORIZATION FOR REPRODUCTION OF MASTER’S THESIS X I grant permission for the reproduction of this thesis in part or in its entirety without further authorization from me, on the condition that the person or agency requesting reproduction absorbs the cost and provides proper acknowledgment of authorship.