An Archeology of Postmoden Architecture: a Reading of Charles Jencks' Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pritzker Architecture Prize Laureate

For publication on or after Monday, March 29, 2010 Media Kit announcing the 2010 PritzKer architecture Prize Laureate This media kit consists of two booklets: one with text providing details of the laureate announcement, and a second booklet of photographs that are linked to downloadable high resolution images that may be used for printing in connection with the announcement of the Pritzker Architecture Prize. The photos of the Laureates and their works provided do not rep- resent a complete catalogue of their work, but rather a small sampling. Contents Previous Laureates of the Pritzker Prize ....................................................2 Media Release Announcing the 2010 Laureate ......................................3-5 Citation from Pritzker Jury ........................................................................6 Members of the Pritzker Jury ....................................................................7 About the Works of SANAA ...............................................................8-10 Fact Summary .....................................................................................11-17 About the Pritzker Medal ........................................................................18 2010 Ceremony Venue ......................................................................19-21 History of the Pritzker Prize ...............................................................22-24 Media contact The Hyatt Foundation phone: 310-273-8696 or Media Information Office 310-278-7372 Attn: Keith H. Walker fax: 310-273-6134 8802 Ashcroft Avenue e-mail: [email protected] Los Angeles, CA 90048-2402 http:/www.pritzkerprize.com 1 P r e v i o u s L a u r e a t e s 1979 1995 Philip Johnson of the United States of America Tadao Ando of Japan presented at Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C. presented at the Grand Trianon and the Palace of Versailles, France 1996 1980 Luis Barragán of Mexico Rafael Moneo of Spain presented at the construction site of The Getty Center, presented at Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C. -

12. Selma Harrington Et Al 11-3-178-192

Selma Harrington, Branka Dimitrijević, Ashraf M. Salama Archnet-IJAR, Volume 11 - Issue 3 - November 2017 - (178-192) – Regular Section Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research www.archnet-ijar.net/ -- https://archnet.org/collections/34 MODERNIST ARCHITECTURE, CONFLICT, HERITAGE AND RESILIENCE: THE CASE OF THE HISTORICAL MUSEUM OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.26687/archnet-ijar.v11i3.1330 Selma Harrington, Branka Dimitrijević, Ashraf M. Salama Keywords Abstract Bosnia and Herzegovina; Bosnia and Herzegovina is one of the successor states of conflict and identity former Yugoslavia, with a history of dramatic conflicts and narratives; Modernist ruptures. These have left a unique heritage of interchanging architecture; public function; prosperity and destruction, in which the built environment and resilience; reuse of architecture provide a rich evidence of the many complex architectural heritage identity narratives. The public function and architecture of the Historical Museum of Bosnia and Herzegovina, once purposely built to commemorate the national liberation in World War 2, encapsulates the current situation in the country, which is navigating through a complicated period of reconstruction and transformation after the war in 1990s. Once considered as the embodiment of a purist Modernist architecture, now a damaged structure with negligible institutional patronage, the Museum shelters the fractured artefacts of life during the three and a half year siege of ArchNet -IJAR is indexed and Sarajevo. This paper introduces research into symbiotic listed in several databases, elements of architecture and public function of the Museum. including: The impact of conflict on its survival, resilience and continuity of use is explored through its potentially mediatory role, and • Avery Index to Architectural modelling for similar cases of reuse of 20th century Periodicals architectural heritage. -

The Making of the Sainsbury Centre the Making of the Sainsbury Centre

The Making of the Sainsbury Centre The Making of the Sainsbury Centre Edited by Jane Pavitt and Abraham Thomas 2 This publication accompanies the exhibition: Unless otherwise stated, all dates of built projects SUPERSTRUCTURES: The New Architecture refer to their date of completion. 1960–1990 Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts Building credits run in the order of architect followed 24 March–2 September 2018 by structural engineer. First published in Great Britain by Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts Norwich Research Park University of East Anglia Norwich, NR4 7TJ scva.ac.uk © Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts, University of East Anglia, 2018 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data. A catalogue record is available from the British Library. ISBN 978 0946 009732 Exhibition Curators: Jane Pavitt and Abraham Thomas Book Design: Johnson Design Book Project Editor: Rachel Giles Project Curator: Monserrat Pis Marcos Printed and bound in the UK by Pureprint Group First edition 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Superstructure The Making of the Sainsbury Centre for Visual Arts Contents Foreword David Sainsbury 9 Superstructures: The New Architecture 1960–1990 12 Jane Pavitt and Abraham Thomas Introduction 13 The making of the Sainsbury Centre 16 The idea of High Tech 20 Three early projects 21 The engineering tradition 24 Technology transfer and the ‘Kit of Parts’ 32 Utopias and megastructures 39 The corporate ideal 46 Conclusion 50 Side-slipping the Seventies Jonathan Glancey 57 Under Construction: Building the Sainsbury Centre 72 Bibliography 110 Acknowledgements 111 Photographic credits 112 6 Fo reword David Sainsbury Opposite. -

Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, Ve Aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 2013 Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, vE aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites Jonathan Vimr University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Vimr, Jonathan, "Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, vE aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites" (2013). Theses (Historic Preservation). 211. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/211 Suggested Citation: Vimr, Jonathan (2013). Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, vE aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/211 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Protecting Postmodern Historicism: Identification, vE aluation, and Prescriptions for Preeminent Sites Abstract Just as architectural history traditionally takes the form of a march of styles, so too do preservationists repeatedly campaign to save seminal works of an architectural manner several decades after its period of prominence. This is currently happening with New Brutalism and given its age and current unpopularity will likely soon befall postmodern historicism. In hopes of preventing the loss of any of the manner’s preeminent works, this study provides professionals with a framework for evaluating the significance of postmodern historicist designs in relation to one another. Through this, the limited resources required for large-scale preservation campaigns can be correctly dedicated to the most emblematic sites. Three case studies demonstrate the application of these criteria and an extended look at recent preservation campaigns provides lessons in how to best proactively preserve unpopular sites. -

An Introduction to Architectural Theory Is the First Critical History of a Ma Architectural Thought Over the Last Forty Years

a ND M a LLGR G OOD An Introduction to Architectural Theory is the first critical history of a ma architectural thought over the last forty years. Beginning with the VE cataclysmic social and political events of 1968, the authors survey N the criticisms of high modernism and its abiding evolution, the AN INTRODUCT rise of postmodern and poststructural theory, traditionalism, New Urbanism, critical regionalism, deconstruction, parametric design, minimalism, phenomenology, sustainability, and the implications of AN INTRODUCTiON TO new technologies for design. With a sharp and lively text, Mallgrave and Goodman explore issues in depth but not to the extent that they become inaccessible to beginning students. ARCHITECTURaL THEORY i HaRRY FRaNCiS MaLLGRaVE is a professor of architecture at Illinois Institute of ON TO 1968 TO THE PRESENT Technology, and has enjoyed a distinguished career as an award-winning scholar, translator, and editor. His most recent publications include Modern Architectural HaRRY FRaNCiS MaLLGRaVE aND DaViD GOODmaN Theory: A Historical Survey, 1673–1968 (2005), the two volumes of Architectural ARCHITECTUR Theory: An Anthology from Vitruvius to 2005 (Wiley-Blackwell, 2005–8, volume 2 with co-editor Christina Contandriopoulos), and The Architect’s Brain: Neuroscience, Creativity, and Architecture (Wiley-Blackwell, 2010). DaViD GOODmaN is Studio Associate Professor of Architecture at Illinois Institute of Technology and is co-principal of R+D Studio. He has also taught architecture at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design and at Boston Architectural College. His work has appeared in the journal Log, in the anthology Chicago Architecture: Histories, Revisions, Alternatives, and in the Northwestern University Press publication Walter Netsch: A Critical Appreciation and Sourcebook. -

The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: the Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry Versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry

Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture Volume 5 Issue 2 135-172 2015 The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry Nelly Shafik Ramzy Sinai University Follow this and additional works at: https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal Part of the Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons Recommended Citation Ramzy, Nelly Shafik. "The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry." Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture 5, 2 (2015): 135-172. https://digital.kenyon.edu/perejournal/vol5/iss2/7 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Art History at Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Peregrinations: Journal of Medieval Art and Architecture by an authorized editor of Digital Kenyon: Research, Scholarship, and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ramzy The Dual Language of Geometry in Gothic Architecture: The Symbolic Message of Euclidian Geometry versus the Visual Dialogue of Fractal Geometry By Nelly Shafik Ramzy, Department of Architectural Engineering, Faculty of Engineering Sciences, Sinai University, El Masaeed, El Arish City, Egypt 1. Introduction When performing geometrical analysis of historical buildings, it is important to keep in mind what were the intentions -

Pritzker Prize to Doshi, Designer for Humanity in Search of a Win-Win

03.19.18 GIVING VOICE TO THOSE WHO CREATE WORKPLACE DESIGN & FURNISHINGS Pritzker Prize to Doshi, Designer for Humanity The 2018 Pritzker Prize, universally considered the highest honor for an architect, will be conferred this year on the 90-year- old Balkrishna Doshi, the first Indian so honored. The citation from the Pritzker jury recognizes his particular strengths by stating that he “has always created architecture that is serious, never flashy or a follower of trends.” The never-flashy-or-trendy message is another indication from these arbiters of design that our infatuation with exotic three-dimensional configurations initiated by Frank Gehry and Zaha Hadid – and emulated by numerous others – may have run its course. FULL STORY ON PAGE 3… In Search of a Win-Win: The Value Engineering Process When most design professionals hear the term value engineering, a dreaded sinking feeling deep in the pit of their stomach ensues. Both the design firm and the contractor are at a disadvantage in preserving the look and design intent of the project, keeping construction costs to a minimum, and delivering the entire package on time. officeinsight contributorPeter Carey searches for solutions that make it all possible. FULL STORY ON PAGE 14… Concurrents – Environmental Psychology: Swedish Death Cleaning First, Chunking Second Swedish death cleaning has replaced hygge as the hottest Scandinavian life management tool in the U.S. Margareta CITED: Magnussen’s system for de-cluttering, detailed in her book, The “OUR FATE ONLY SEEMS Gentle Art of Swedish Death Cleaning: How to Make Your Loved HORRIBLE WHEN WE PLACE Ines’ Lives Easier and Your Own Life More Pleasant, is a little IT IN CONTRAST WITH more straightforward than Marie Kondo’s more sentimental tact, SOMETHING THAT WOULD SEEM PREFERABLE.” described in The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up. -

Baroque & Modern Expression

HISTORY OF ARCHITECTURAL THEORY, 48-311, Fall 2016 Prof. Gutschow, Week #4 Week #4: BAROQUE & MODERN EXPRESSION Tu./Th. Sept. 20/22 Required Readings for all Students: * H.F. Mallgrave, Architectural Theory: Vol.1: An Anthology from Vitruvius to 1870 (2006), pp.48-55, 57-117, 223-248. Focus especially on readings #29,31,32,34,35,37,39,40,92,94,99,100. Questions to think about: In your reading of the many excerpts associated with the Baroque, attempt to get an overview of how the Baroque period and mood is different than the Renaissance. What was the “battle of the ancients & moderns,” and who were the main players? How does the architectural theory conversation in France compare to that in England? What is “Palladianism,” and how does it relate to the “Baroque”? How does garden design start to skew the theoretical trajectory in England? What is “the picturesque”? * Perrault, C. Ordonnance for the Five Kinds of Columns after the Method of the Ancients = Ordonnances des Cinq Espèces de Colonne, intro. A. Pérez-Gómez (1683, 1993) pp.47-63, 65-66, 94-95, 153-154, skim155-175 Questions to think about: What are “Postive” and “Arbitrary” beauty? Which does Perrault favor? Why? What is Perrault’s attitude towards the “ancients”? How do Perrault’s Baroque ideas challenge Vitruvius and Renaissance architectural theory? Assigned/Other Readings: Questions to think about for all readings: What attributes does each author give to the Baroque, as opposed to the Renaissance? What theory does the author propose for why the Baroque evolved out of the Renaissance? How are the theoretical books and works of the Baroque different than the “treatises” of the Renaissance? Wölfflin, Heinrich. -

On the First Pop Age

hal foster ON THE FIRST POP AGE n epic poem of early Pop by the architects Alison and Peter Smithson, in an essay published in November 1956, Athree months after the landmark Independent Group exhibition ‘This is Tomorrow’ opens at the Whitechapel Gallery: ‘Gropius wrote a book on grain silos, Le Corbusier one on aeroplanes, and Charlotte Perriand brought a new object to the office every morning; but today we collect ads.’ Forget that Gropius, Corbusier and Perriand were also media-savvy; the point is polemical: they, the protagonists of modernist design, were cued by functional structures, vehicles, things, but we, the celebrants of Pop culture, look to ‘the throw- away object and the pop-package’ for our models. This is done partly in delight, the Smithsons suggest, and partly in desperation: ‘Today we are being edged out of our traditional role by the new phenomenon of the popular arts—advertising . We must somehow get the measure of this intervention if we are to match its powerful and exciting impulses with our own.’1 Others in the IG, Reyner Banham and Richard Hamilton above all, share this urgency. 1 Who are the prophets of this epic shift? The first we to ‘collect ads’ is Eduardo Paolozzi, who calls the collages made from his collection ‘Bunk’ (an ambivalent homage to Henry Ford?). Although this ‘pinboard aesthetic’ is also practised by Nigel Henderson, William Turnbull and John McHale, it is Paolozzi who, one night in April 1952, projects his ads, maga zine clippings, postcards and diagrams at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, in a demonstration that underwrites the distinctive method of the IG, an anti-hierarchical juxtaposition of archival images disparate, connected, or both at once. -

Architecture (ARCH) 1

Architecture (ARCH) 1 their architectural use. ARCH 504 Materials and Building Construction ARCHITECTURE (ARCH) II (3) This first-year graduate seminar course will continue to present students with information on fundamental and advanced building ARCH 501: Analysis of Architectural Precedents: Ancient Industrial materials and systems and on construction technologies associated with Revolution their architectural use. Students will also consider the advancements in architectural materials and technologies. It is the second part of 3 Credits a two-semester sequence preceded by ARCH 503. Recurrent course Analysis of architectural precendents from antiquity to the turn of the themes include 1) architecture as a product of culture (wisdom, abilities, twentieth century through methodologies emphasizing research and aspirations), 2) architecture as a product of place (materials, tools, critical inquiry. The 20th century Italian architectural historian and topography, climate), the relationship between architectural appearance theorist Manfredo Tafuri argued that architecture was intrinsically presented and the mode of construction employed, 3) materials and forward-looking and utopian: "project" in both the sense of "a design making as an expression of an idea and 4) the relationship of a building project" and a leap into the future, like "projectile" or "projection." However, whole to a detail. This course is motivated by these concerns: a firm he also argued that architectural history, understood deeply and critically, belief that architects -

Aesthetics Between History, Geography and Media

volume 11 _2019 No _2 s e r b i a n a r c hS i t e c t u rA a l j o u rJ n a l ICA 2019 21ST ICA POSSIBLE WORLDS OF CONTEMPORARY AESTHETICS: AESTHETICS BETWEEN HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY AND MEDIA PART 1 _2019_2_ Serbian Architectural Journal is published in Serbia by the University of Belgrade, Faculty of Architecture, with The Centre for Ethics, Law and Applied Philosophy, and distributed by the same institutions / www.saj.rs All rights reserved. No part of this jornal may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means [including photocopying, recording or information storage and retrieval] without permission in writing from the publisher. This and other publisher’s books may be purchased at special quantity discounts for business or sales promotional use. For informations, please email at [email protected] or write to following adress. Send editorial correspondence to: Serbian Architectural Journal Faculty of Architecture Bulevar Kralja Aleksandra 73/II 11 120 Belgrade, Serbia ISSN 1821-3952 cover image: Official Conference Graphics, Boško Drobnjak, 2019. s e r b i a n a r c hS i t e c t u rA a l j o u rJ n a l 21ST ICA POSSIBLE WORLDS OF CONTEMPORARY AESTHETICS: AESTHETICS BETWEEN HISTORY, GEOGRAPHY AND MEDIA volume 11 _2019 No _2 PART 1 _2019_2_ s e r b i a n a r c h i t e c t u r a l j o u r n a l EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Vladan Djokić EDITORIAL BOARD: Petar Bojanić, University of Belgrade, Institute for Philosophy and Social Theory, Serbia; University of Rijeka, CAS – SEE, Croatia Vladan Djokić, University of Belgrade, -

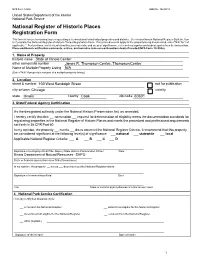

Thompson Center, Thompson Center Name of Multiple Property Listing N/A (Enter "N/A" If Property Is Not Part of a Multiple Property Listing)

NPS Form 10900 OMB No. 10240018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name State of Illinois Center other names/site number James R. Thompson Center, Thompson Center Name of Multiple Property Listing N/A (Enter "N/A" if property is not part of a multiple property listing) 2. Location street & number 100 West Randolph Street not for publication city or town Chicago vicinity state Illinois county Cook zip code 60601 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this nomination request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: national statewide local Applicable National Register Criteria: A B C D Signature of certifying official/Title: Deputy State Historic Preservation Officer Date Illinois Department of Natural Resources - SHPO State or Federal agency/bureau or Tribal Government In my opinion, the property meets does not meet the National Register criteria.