Here a Group of Drunks Are Arguing Loudly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COVID-19 Emergency Services Manhattan Resource Guide

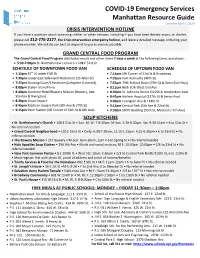

COVID-19 Emergency Services Manhattan Resource Guide Updated April 6, 2020 CRISIS INTERVENTION HOTLINE If you have a question about accessing shelter or other services, including if you have been denied access to shelter, please call 212-776-2177, the Crisis Intervention emergency hotline, and leave a detailed message, including your phone number. We will do our best to respond to you as soon as possible. GRAND CENTRAL FOOD PROGRAM The Grand Central Food Program distributes meals and other items 7 days a week at the following times and places: 5:30-7:00pm St. Bartholomew's Church • 108 E 51st St SCHEDULE OF DOWNTOWN FOOD VAN SCHEDULE OF UPTOWN FOOD VAN th 7:15pm 35 St under FDR Dr 7:15pm SW Corner of 51st St & Broadway 7:30pm Lower East Side Harm Reduction (25 Allen St) 7:35pm Port Authority (40th St) 7:45pm Housing Court/Chinatown (Lafayette /Leonard) 7:55pm 79th St Boat Basin (79th St & West Side Hwy) 8:00pm Staten Island Ferry 8:15pm 86th St & West End Ave 8:20pm Sunshine Hotel/Bowery Mission (Bowery, btw 8:30pm St. John the Divine (112th & Amsterdam Ave) Stanton & Rivington) 8:45pm Harlem Hospital (137th St & Lenox Ave) 8:30pm Union Square 9:00pm Lexington Ave & 124th St 8:45pm Madison Square Park (5th Ave & 27th St) 9:15pm Central Park (5th Ave & 72nd St) 9:15pm Penn Station (NE Corner of 34th St & 8th Ave) 9:30pm SONY Building (55th St, Madison / 5th Ave) SOUP KITCHENS • St. Bartholomew's Church • 108 E 51st St • Sun, M, W: 7-8:30am; M-Sun: 5:30-6:30pm; Sat: 9:30-11am • 6 to 51st St • No referral needed • Grand -

From Free Cinema to British New Wave: a Story of Angry Young Men

SUPLEMENTO Ideas, I, 1 (2020) 51 From Free Cinema to British New Wave: A Story of Angry Young Men Diego Brodersen* Introduction In February 1956, a group of young film-makers premiered a programme of three documentary films at the National Film Theatre (now the BFI Southbank). Lorenza Mazzetti, Lindsay Anderson, Karel Reisz and Tony Richardson thought at the time that “no film can be too personal”, and vehemently said so in their brief but potent manifesto about Free Cinema. Their documentaries were not only personal, but aimed to show the real working class people in Britain, blending the realistic with the poetic. Three of them would establish themselves as some of the most inventive and irreverent British filmmakers of the 60s, creating iconoclastic works –both in subject matter and in form– such as Saturday Day and Sunday Morning, The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner and If… Those were the first significant steps of a New British Cinema. They were the Big Screen’s angry young men. What is British cinema? In my opinion, it means many different things. National cinemas are much more than only one idea. I would like to begin this presentation with this question because there have been different genres and types of films in British cinema since the beginning. So, for example, there was a kind of cinema that was very successful, not only in Britain but also in America: the films of the British Empire, the films about the Empire abroad, set in faraway places like India or Egypt. Such films celebrated the glory of the British Empire when the British Empire was almost ending. -

New York, New York

EXPOSITION NEW YORK, NEW YORK Cinquante ans d’art, architecture, cinéma, performance, photographie et vidéo Du 14 juillet au 10 septembre 2006 Grimaldi Forum - Espace Ravel INTRODUCTION L’exposition « NEW YORK, NEW YORK » cinquante ans d’art, architecture, cinéma, performance, photographie et vidéo produite par le Grimaldi Forum Monaco, bénéficie du soutien de la Compagnie Monégasque de Banque (CMB), de SKYY Vodka by Campari, de l’Hôtel Métropole à Monte-Carlo et de Bentley Monaco. Commissariat : Lisa Dennison et Germano Celant Scénographie : Pierluigi Cerri (Studio Cerri & Associati, Milano) Renseignements pratiques • Grimaldi Forum : 10 avenue Princesse Grace, Monaco – Espace Ravel. • Horaires : Tous les jours de 10h00 à 20h00 et nocturne les jeudis de 10h00 à 22h00 • Billetterie Grimaldi Forum Tél. +377 99 99 3000 - Fax +377 99 99 3001 – E-mail : [email protected] et points FNAC • Site Internet : www.grimaldiforum.mc • Prix d’entrée : Plein tarif = 10 € Tarifs réduits : Groupes (+ 10 personnes) = 8 € - Etudiants (-25 ans sur présentation de la carte) = 6 € - Enfants (jusqu’à 11 ans) = gratuit • Catalogue de l’exposition (versions française et anglaise) Format : 24 x 28 cm, 560 pages avec 510 illustrations Une coédition SKIRA et GRIMALDI FORUM Auteurs : Germano Celant et Lisa Dennison N°ISBN 88-7624-850-1 ; dépôt légal = juillet 2006 Prix Public : 49 € Communication pour l’exposition : Hervé Zorgniotti – Tél. : 00 377 99 99 25 02 – [email protected] Nathalie Pinto – Tél. : 00 377 99 99 25 03 – [email protected] Contact pour les visuels : Nadège Basile Bruno - Tél. : 00 377 99 99 25 25 – [email protected] AUTOUR DE L’EXPOSITION… Grease Etes-vous partant pour une virée « blouson noir, gomina et look fifties» ? Si c’est le cas, ne manquez pas la plus spectaculaire comédie musicale de l’histoire du rock’n’roll : elle est annoncée au Grimaldi Forum Monaco, pour seulement une semaine et une seule, du 25 au 30 juillet. -

Faculty and Staff Activities 2014–2015

FACULTY AND STAFF ACTIVITIES 2014–2015 COOPER AT ARCHITECTURE Professor Diana Agrest’s film “The Making of an Avant- Assistant Professor Adjunct John Hartmann, co-founder Visiting Professor Joan Ockman was a co-editor for MAS: Garde: The Institute for Architecture and Urban Studies with Lauren Crahan of Freecell Architecture, spoke at The The Modern Architecture Symposia 1962-1966: A Critical Edition 1967-1984” was screened at the Graham Foundation, Hammons School of Architecture at Drury University as part (Yale University Press). The publication was reviewed in Princeton University, Cornell University, UC Berkeley of the 2014-2015 Lecture Series. Architectural Record. She was a presenter at The Building EDITED BY EMMY MIKELSON; DESIGN BY INESSA SHKOLNIKOV, CENTER FOR DESIGN AND TYPOGRAPHY; PHOTOGRAPHY BY JOÃO ENXUTO WITH SPECIAL ASSISTANCE FROM THE SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE ARCHIVE AND ELIZABETH O’DONNELL, ACTING DEAN ARCHIVE AND ELIZABETH O’DONNELL, ACTING FROM THE SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE WITH SPECIAL ASSISTANCE ENXUTO BY JOÃO DESIGN AND TYPOGRAPHY; PHOTOGRAPHY CENTER FOR SHKOLNIKOV, EDITED BY EMMY MIKELSON; DESIGN INESSA College of Environmental Design and followed by a panel Symposium held at Columbia University GSAPP. discussion with Agrest, Nicholas de Monchaux, Sylvia Lavin Director of the School of Architecture Archive, and Stanley Saitowitz, the 10th Annual Cinema Orange Film Steven Hillyer, co-produced Christmas Without Tears, Acting Dean and Professor Elizabeth O’Donnell was the Series, Newport Beach Film Festival at Orange County a four-city tour of holiday-themed variety shows hosted co-chair and delivered the introductory remarks for Museum of Art, the San Diego Design Film Festival, and Cite by Judith Owen and Harry Shearer, which included “The Sultanate of Oman: Geography, Religion and Culture” de l’Architecture in Paris, France, which was followed by a performances by Mario Cantone, Catherine O’Hara, held at The Cooper Union. -

Albany County

Navigator Agency Site Locations In light of the situation surrounding the Coronavirus, please call ahead before arriving at any site location, as the location may have temporarily changed. County: Albany Lead Agency Name Healthy Capital District Initiative Subcontractor's Name N/A Enrollment Site Name Cohoes Senior Center Site Address 10 Cayuga Plaza City Cohoes NY 12047 Phone # (518) 462-7040 Languages English & Spanish Lead Agency Name Community Service Society of New York Subcontractor's Name Public Policy and Education Fund Enrollment Site Name Capital City Rescue Mission Free Clinic Site Address 88 Trinity Place City Albany NY 12202 Phone # (800) 803-8508 Languages English & Spanish Lead Agency Name Community Service Society of New York Subcontractor's Name Public Policy and Education Fund Enrollment Site Name Albany County Department of Health Clinic Site Address 175 Green Street City Albany NY 12202 Phone # (800) 803-8508 Languages English & Spanish Lead Agency Name Community Service Society of New York Subcontractor's Name Public Policy and Education Fund Enrollment Site Name Addiction Care Center of Albany Site Address 90 McCarty Avenue City Albany NY 12202 Phone # (800) 803-8508 Languages English & Spanish Lead Agency Name Community Service Society of New York Subcontractor's Name Public Policy and Education Fund Enrollment Site Name Trinity Center Site Address 15 Trinity Place City Albany NY 12202 Phone # (800) 803-8508 Languages English & Spanish NYS Department of Health Report Date: 9/1/2021 Navigator Agency Site Locations In light of the situation surrounding the Coronavirus, please call ahead before arriving at any site location, as the location may have temporarily changed. -

![THIS IS MICHIGAN “[Here at Michigan] Olympians Coach Me](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9289/this-is-michigan-here-at-michigan-olympians-coach-me-559289.webp)

THIS IS MICHIGAN “[Here at Michigan] Olympians Coach Me

THIS IS MICHIGAN “[Here at Michigan] Olympians coach me. Nobel Prize winners lecture me. I eat lunch with All-Americans. In the athletic training room, I sit next to Big Ten champions. I meet with prize-winning authors during their office hours. I take class notes next to American record holders. I walk to class with members of national championship teams. I open doors once opened by Oscar-winning actors, former Presidents and astronauts ... it’s all in the day of a Michigan student-athlete.” Shelley Johnson Former Michigan Field Hockey Player In January 2008, Forbes.com rated the University of Michigan No. 1 on it's list of "Champion Factories." Examining the current rosters at that time in the NFL, NBA, NHL, Major League Baseball and Major League Soccer, 68 professional athletes competed collegiately at Michigan. Among the U-M alumni were 21 hockey players, including Dallas Stars goaltender Marty Turco; three baseball players, three basketball players, including Dallas Mavericks forward Juwan Howard; and 41 football players, includ- ing New England QB Tom Brady. A 2005 157-pound 2005 Women's College World Series Champions NCAA Champion Ryan Bertin NCAA Michigan's 2007-08 NCAA Champions: Emily Brunneman (1,650-yard freestyle); Alex Vanderkaay (400-yard individual med- EXCELLENCE ley), Tiffany Ofili (indoor 60-meter hurdles and outdoor 100-meter hurdles); and Michigan athletic teams have claimed Geena Gall (800-meter run). 52 national championships in 12 sports over the years, beginning with foot- ball's 1901 national title. Since then, Wolverine dynasties have developed in football, men's swimming and diving and ice hockey. -

Boxoffice Barometer (March 6, 1961)

MARCH 6, 1961 IN TWO SECTIONS SECTION TWO Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents William Wyler’s production of “BEN-HUR” starring CHARLTON HESTON • JACK HAWKINS • Haya Harareet • Stephen Boyd • Hugh Griffith • Martha Scott • with Cathy O’Donnell • Sam Jaffe • Screen Play by Karl Tunberg • Music by Miklos Rozsa • Produced by Sam Zimbalist. M-G-M . EVEN GREATER IN Continuing its success story with current and coming attractions like these! ...and this is only the beginning! "GO NAKED IN THE WORLD” c ( 'KSX'i "THE Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents GINA LOLLOBRIGIDA • ANTHONY FRANCIOSA • ERNEST BORGNINE in An Areola Production “GO SPINSTER” • • — Metrocolor) NAKED IN THE WORLD” with Luana Patten Will Kuluva Philip Ober ( CinemaScope John Kellogg • Nancy R. Pollock • Tracey Roberts • Screen Play by Ranald Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer pre- MacDougall • Based on the Book by Tom T. Chamales • Directed by sents SHIRLEY MacLAINE Ranald MacDougall • Produced by Aaron Rosenberg. LAURENCE HARVEY JACK HAWKINS in A Julian Blaustein Production “SPINSTER" with Nobu McCarthy • Screen Play by Ben Maddow • Based on the Novel by Sylvia Ashton- Warner • Directed by Charles Walters. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents David O. Selznick's Production of Margaret Mitchell’s Story of the Old South "GONE WITH THE WIND” starring CLARK GABLE • VIVIEN LEIGH • LESLIE HOWARD • OLIVIA deHAVILLAND • A Selznick International Picture • Screen Play by Sidney Howard • Music by Max Steiner Directed by Victor Fleming Technicolor ’) "GORGO ( Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents “GORGO” star- ring Bill Travers • William Sylvester • Vincent "THE SECRET PARTNER” Winter • Bruce Seton • Joseph O'Conor • Martin Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer presents STEWART GRANGER Benson • Barry Keegan • Dervis Ward • Christopher HAYA HARAREET in “THE SECRET PARTNER” with Rhodes • Screen Play by John Loring and Daniel Bernard Lee • Screen Play by David Pursall and Jack Seddon Hyatt • Directed by Eugene Lourie • Executive Directed by Basil Dearden • Produced by Michael Relph. -

Anthology Film Archives 104

242. Sweet Potato PieCl 384. Jerusalem - Hadassah Hospital #2 243. Jakob Kohn on eaver-Leary 385. Jerusalem - Old Peoples Workshop, Golstein Village THE 244. After the Bar with Tony and Michael #1 386. Jerusalem - Damascus Gate & Old City 245. After the Bar with Tony and Michael #2 387. Jerusalem -Songs of the Yeshiva, Rabbi Frank 246. Chiropractor 388. Jerusalem -Tomb of Mary, Holy Sepulchre, Sations of Cross 247. Tosun Bayrak's Dinner and Wake 389. Jerusalem - Drive to Prison 248. Ellen's Apartment #1 390. Jerusalem - Briss 249. Ellen's Apartment #2 391 . European Video Resources 250. Ellen's Apartment #3 392. Jack Moore in Amsterdam 251, Tuli's Montreal Revolt 393. Tajiri in Baarlo, Holland ; Algol, Brussels VIDEOFIiEEX Brussels MEDIABUS " LANESVILLE TV 252. Asian Americans My Lai Demonstration 394. Video Chain, 253. CBS - Cleaver Tapes 395. NKTV Vision Hoppy 254. Rhinoceros and Bugs Bunny 396. 'Gay Liberation Front - London 255. Wall-Gazing 397. Putting in an Eeel Run & A Social Gathering 256. The Actress -Sandi Smith 398. Don't Throw Yer Cans in the Road Skip Blumberg 257. Tai Chi with George 399. Bart's Cowboy Show 258. Coke Recycling and Sheepshead Bay 400. Lanesville Overview #1 259. Miami Drive - Draft Counsel #1 401 . Freex-German TV - Valeska, Albert, Constanza Nancy Cain 260. Draft Counsel #2 402, Soup in Cup 261 . Late Nite Show - Mother #1 403. Lanesville TV - Easter Bunny David Cort 262. Mother #2 404. LanesvilleOverview #2 263. Lenneke and Alan Singing 405. Laser Games 264. LennekeandAlan intheShower 406. Coyote Chuck -WestbethMeeting -That's notRight Bart Friedman 265. -

The Field Guide to Sponsored Films

THE FIELD GUIDE TO SPONSORED FILMS by Rick Prelinger National Film Preservation Foundation San Francisco, California Rick Prelinger is the founder of the Prelinger Archives, a collection of 51,000 advertising, educational, industrial, and amateur films that was acquired by the Library of Congress in 2002. He has partnered with the Internet Archive (www.archive.org) to make 2,000 films from his collection available online and worked with the Voyager Company to produce 14 laser discs and CD-ROMs of films drawn from his collection, including Ephemeral Films, the series Our Secret Century, and Call It Home: The House That Private Enterprise Built. In 2004, Rick and Megan Shaw Prelinger established the Prelinger Library in San Francisco. National Film Preservation Foundation 870 Market Street, Suite 1113 San Francisco, CA 94102 © 2006 by the National Film Preservation Foundation Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Prelinger, Rick, 1953– The field guide to sponsored films / Rick Prelinger. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-9747099-3-X (alk. paper) 1. Industrial films—Catalogs. 2. Business—Film catalogs. 3. Motion pictures in adver- tising. 4. Business in motion pictures. I. Title. HF1007.P863 2006 011´.372—dc22 2006029038 CIP This publication was made possible through a grant from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. It may be downloaded as a PDF file from the National Film Preservation Foundation Web site: www.filmpreservation.org. Photo credits Cover and title page (from left): Admiral Cigarette (1897), courtesy of Library of Congress; Now You’re Talking (1927), courtesy of Library of Congress; Highlights and Shadows (1938), courtesy of George Eastman House. -

From Real Time to Reel Time: the Films of John Schlesinger

From Real Time to Reel Time: The Films of John Schlesinger A study of the change from objective realism to subjective reality in British cinema in the 1960s By Desmond Michael Fleming Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2011 School of Culture and Communication Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne Produced on Archival Quality Paper Declaration This is to certify that: (i) the thesis comprises only my original work towards the PhD, (ii) due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all other material used, (iii) the thesis is fewer than 100,000 words in length, exclusive of tables, maps, bibliographies and appendices. Abstract The 1960s was a period of change for the British cinema, as it was for so much else. The six feature films directed by John Schlesinger in that decade stand as an exemplar of what those changes were. They also demonstrate a fundamental change in the narrative form used by mainstream cinema. Through a close analysis of these films, A Kind of Loving, Billy Liar, Darling, Far From the Madding Crowd, Midnight Cowboy and Sunday Bloody Sunday, this thesis examines the changes as they took hold in mainstream cinema. In effect, the thesis establishes that the principal mode of narrative moved from one based on objective realism in the tradition of the documentary movement to one which took a subjective mode of narrative wherein the image on the screen, and the sounds attached, were not necessarily a record of the external world. The world of memory, the subjective world of the mind, became an integral part of the narrative. -

The Poetry Project Newsletter

THE POETRY PROJECT NEWSLETTER $5.00 #212 OCTOBER/NOVEMBER 2007 How to Be Perfect POEMS BY RON PADGETT ISBN: 978-1-56689-203-2 “Ron Padgett’s How to Be Perfect is. New Perfect.” —lyn hejinian Poetry Ripple Effect: from New and Selected Poems BY ELAINE EQUI ISBN: 978-1-56689-197-4 Coffee “[Equi’s] poems encourage readers House to see anew.” —New York Times The Marvelous Press Bones of Time: Excavations and Explanations POEMS BY BRENDA COULTAS ISBN: 978-1-56689-204-9 “This is a revelatory book.” —edward sanders COMING SOON Vertigo Poetry from POEMS BY MARTHA RONK Anne Boyer, ISBN: 978-1-56689-205-6 Linda Hogan, “Short, stunning lyrics.” —Publishers Weekly Eugen Jebeleanu, (starred review) Raymond McDaniel, A.B. Spellman, and Broken World Marjorie Welish. POEMS BY JOSEPH LEASE ISBN: 978-1-56689-198-1 “An exquisite collection!” —marjorie perloff Skirt Full of Black POEMS BY SUN YUNG SHIN ISBN: 978-1-56689-199-8 “A spirited and restless imagination at work.” Good books are brewing at —marilyn chin www.coffeehousepress.org THE POETRY PROJECT ST. MARK’S CHURCH in-the-BowerY 131 EAST 10TH STREET NEW YORK NY 10003 NEWSLETTER www.poetryproject.com #212 OCTOBER/NOVEMBER 2007 NEWSLETTER EDITOR John Coletti WELCOME BACK... DISTRIBUTION Small Press Distribution, 1341 Seventh St., Berkeley, CA 94710 4 ANNOUNCEMENTS THE POETRY PROJECT LTD. STAFF ARTISTIC DIRECTOR Stacy Szymaszek PROGRAM COORDINATOR Corrine Fitzpatrick PROGRAM ASSISTANT Arlo Quint 6 WRITING WORKSHOPS MONDAY NIGHT COORDINATOR Akilah Oliver WEDNESDAY NIGHT COORDINATOR Stacy Szymaszek FRIDAY NIGHT COORDINATOR Corrine Fitzpatrick 7 REMEMBERING SEKOU SUNDIATA SOUND TECHNICIAN David Vogen BOOKKEEPER Stephen Rosenthal DEVELOpmENT CONSULTANT Stephanie Gray BOX OFFICE Courtney Frederick, Erika Recordon, Nicole Wallace 8 IN CONVERSATION INTERNS Diana Hamilton, Owen Hutchinson, Austin LaGrone, Nicole Wallace A CHAT BETWEEN BRENDA COULTAS AND AKILAH OLIVER VOLUNTEERS Jim Behrle, David Cameron, Christine Gans, HR Hegnauer, Sarah Kolbasowski, Dgls. -

Evergreen Review on Film, Mar 16—31

BAMcinématek presents From the Third Eye: Evergreen Review on Film, Mar 16—31 Marking the release of From the Third Eye: The Evergreen Film Reader, a new anthology of works published in the seminal counterculture journal, BAMcinématek pays homage to a bygone era of provocative cinema The series kicks off with a week-long run of famed documentarian Leo Hurwitz’s Strange Victory in a new restoration The Wall Street Journal is the title sponsor for BAMcinématek and BAM Rose Cinemas. Feb 17, 2016/Brooklyn, NY—From Wednesday, March 16, through Thursday, March 31, BAMcinématek presents From the Third Eye: Evergreen Review on Film. Founded and managed by legendary Grove Press publisher Barney Rosset, Evergreen Review brought the best in radical art, literature, and politics to newsstands across the US from the late 1950s to the early 1970s. Grove launched its film division in the mid-1960s and quickly became one of the most important and innovative film distributors of its time, while Evergreen published incisive essays on cinema by writers like Norman Mailer, Amos Vogel, Nat Hentoff, Parker Tyler, and many others. Marking the publication of From the Third Eye: The Evergreen Review Film Reader, edited by Rosset and critic Ed Halter, this series brings together a provocative selection of the often controversial films that were championed by this seminal publication—including many distributed by Grove itself—vividly illustrating how filmmakers worked to redefine cinema in an era of sexual, social, and political revolution. The series begins with a week-long run of a new restoration of Leo Hurwitz’s Strange Victory (1948/1964), “the most ambitious leftist film made in the US” (J.