Denzel Washington

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Learning About American History Through Great Films the Crucible

Learning About American History Through Great Films The Crucible. A story based on the Salem witchcraft trials, capturing the sense of hysteria in the 1600’s but also the red scare (McCarthyism) of the 1950’s. 1776. A musical account of the events leading up to the writing of the Declaration of Independence. Roots. A video presentation of an award-winning family saga (six part series), starting with their arrival as slaves in America. The Patriot. True historical figures form the background for the major character in this film set during the Revolutionary War. Amistad The story of a slave revolt in 1839, it started a controversy that pitted the courts against the President. A milestone in the development of the abolitionist movement. Twelve Years a Slave. Winner of Academy Award for best picture of 2013, the movie is based on the book by Solomon Northrop, who was kidnapped from his New England home and forced into slavery in the South for 12 years. Lincoln. This movie focuses on the struggle to have the 13th amendment to abolish slavery enacted by congress. Daniel Day Lewis won best actor for his performance. Gettysburg. Classic Civil War movie detailing the most important battle of American history. Glory. Civil War movie chronicles the 54th Regiment of Massachusetts, an African American unit that fought bravely to win freedom for all slaves. Denzel Washington won an Oscar for his role. Dances with Wolves. A disillusioned soldier leaves the Civil War battlefield and strikes out on his own. He eventually learns to love and respect the land, when Sioux Indians welcome him into their tribe. -

It's a Conspiracy

IT’S A CONSPIRACY! As a Cautionary Remembrance of the JFK Assassination—A Survey of Films With A Paranoid Edge Dan Akira Nishimura with Don Malcolm The only culture to enlist the imagination and change the charac- der. As it snows, he walks the streets of the town that will be forever ter of Americans was the one we had been given by the movies… changed. The banker Mr. Potter (Lionel Barrymore), a scrooge-like No movie star had the mind, courage or force to be national character, practically owns Bedford Falls. As he prepares to reshape leader… So the President nominated himself. He would fill the it in his own image, Potter doesn’t act alone. There’s also a board void. He would be the movie star come to life as President. of directors with identities shielded from the public (think MPAA). Who are these people? And what’s so wonderful about them? —Norman Mailer 3. Ace in the Hole (1951) resident John F. Kennedy was a movie fan. Ironically, one A former big city reporter of his favorites was The Manchurian Candidate (1962), lands a job for an Albu- directed by John Frankenheimer. With the president’s per- querque daily. Chuck Tatum mission, Frankenheimer was able to shoot scenes from (Kirk Douglas) is looking for Seven Days in May (1964) at the White House. Due to a ticket back to “the Apple.” Pthe events of November 1963, both films seem prescient. He thinks he’s found it when Was Lee Harvey Oswald a sleeper agent, a “Manchurian candidate?” Leo Mimosa (Richard Bene- Or was it a military coup as in the latter film? Or both? dict) is trapped in a cave Over the years, many films have dealt with political conspira- collapse. -

Sagawkit Acceptancespeechtran

Screen Actors Guild Awards Acceptance Speech Transcripts TABLE OF CONTENTS INAUGURAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...........................................................................................2 2ND ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .........................................................................................6 3RD ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...................................................................................... 11 4TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 15 5TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 20 6TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 24 7TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 28 8TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 32 9TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 36 10TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 42 11TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 48 12TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .................................................................................... -

Museum of the Moving Image Presents Comprehensive Terrence Malick Retrospective

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MUSEUM OF THE MOVING IMAGE PRESENTS COMPREHENSIVE TERRENCE MALICK RETROSPECTIVE Moments of Grace: The Collected Terrence Malick includes all of his features, some alternate versions, and a preview screening of his new film A Hidden Life November 15–December 8, 2019 Astoria, New York, November 12, 2019—In celebration of Terrence Malick’s new film, the deeply spiritual, achingly ethical, and politically resonant A Hidden Life, Museum of the Moving Image presents the comprehensive retrospective Moments of Grace: The Collected Terrence Malick, from November 15 through December 8. The films in the series span a period of nearly 50 years, opening with Malick’s 1970s breakthroughs Badlands (1973) and Days of Heaven (1978), through his career-revival masterworks The Thin Red Line (1998) and The New World (2005), and continuing with his 21st- century films—from Cannes Palme d’Or winner The Tree of Life (2011); the trio of To the Wonder (2012), Knight of Cups (2015), and Song to Song (2017); and sole documentary project Voyage of Time (2016)—through to this year’s A Hidden Life. Two of these films will be presented in alternate versions—Voyage of Time and The New World—a testament to Malick’s ambitious and exploratory approach to editing. In addition to Malick’s own feature films, the series includes Pocket Money (1972), an ambling buddy comedy with Lee Marvin and Paul Newman, which he wrote (but did not direct), and Thy Kingdom Come (2018), the documentary featurette shot on the set of To the Wonder by photographer Eugene Richards. -

Screenwriters on Screenwriting. the BAFTA and BFI Screenwriters

Screenwriters On Screenwriting. The BAFTA and BFI Screenwriters’ Lecture Series in association with The JJ Charitable Trust Guillermo Arriaga 26 September 2011 at BFI Southbank Guillermo Arriaga: Thank you all for being here. were of the same level, of the same quality, of It’s kind of intimidating with this light, but I hope the first ones. When you’re supposed to gain all it will be good. I have chosen some clips of the the wisdom that age brings with it, man, you films I have written, some of the ones I directed, cannot write good stuff any longer. and I will talk a little about this craft of screenwriting, or storytelling. It happened to Hemingway. A Farewell To Arms for example, is much better than Across The I didn’t study screenwriting at all, ever. I have River. You say, ‘It’s not possible, it’s the same no film studies. Where I come from, where my guy.’ So we never know when this changes. We storytelling comes from, is that need to tell hope it never ends. In my case I am very, very stories. I was saying in an interview that when I bad at adapting. I have no idea how to was a kid I had this gigantic crush on girls. I express the ideas of other people, or to adapt loved girls. But I was too shy to approach them. a novel or do anything like that. I cannot make I’m telling you, when I was nine or ten years old, a living adapting. -

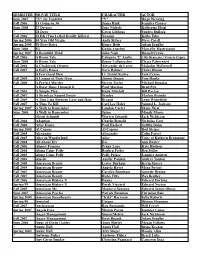

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V

SEMESTER MOVIE TITLE CHARACTER ACTOR Sum 2007 "V" for Vendetta "V" Hugo Weaving Fall 2006 13 Going on 30 Jenna Rink Jennifer Garner Sum 2008 27 Dresses Jane Nichols Katherine Heigl ? 28 Days Gwen Gibbons Sandra Bullock Fall 2006 2LDK (Two Lethal Deadly Killers) Nozomi Koike Eiko Spring 2006 40 Year Old Virgin Andy Stitzer Steve Carell Spring 2005 50 First Dates Henry Roth Adam Sandler Sum 2008 8½ Guido Anselmi Marcello Mastroianni Spring 2007 A Beautiful Mind John Nash Russell Crowe Fall 2006 A Bronx Tale Calogero 'C' Anello Lillo Brancato / Francis Capra Sum 2008 A Bronx Tale Sonny LoSpeecchio Chazz Palmenteri Fall 2006 A Clockwork Orange Alexander de Large Malcolm McDowell Fall 2007 A Doll's House Nora Helmer Claire Bloom ? A Few Good Men Lt. Daniel Kaffee Tom Cruise Fall 2005 A League of Their Own Jimmy Dugan Tom Hanks Fall 2000 A Perfect Murder Steven Taylor Michael Douglas ? A River Runs Through It Paul Maclean Brad Pitt Fall 2005 A Simple Plan Hank Mitchell Bill Paxton Fall 2007 A Streetcar Named Desire Stanley Marlon Brando Fall 2005 A Thin Line Between Love and Hate Brandi Lynn Whitefield Fall 2007 A Time To Kill Carl Lee Haley Samuel L. Jackson Spring 2007 A Walk to Remember Landon Carter Shane West Sum 2008 A Walk to Remember Jaime Mandy Moore ? About Schmidt Warren Schmidt Jack Nickleson Fall 2004 Adaption Charlie/Donald Nicholas Cage Fall 2000 After Hours Paul Hackett Griffin Dunn Spring 2005 Al Capone Al Capone Rod Steiger Fall 2005 Alexander Alexander Colin Farrel Fall 2005 Alice in Wonderland Alice Voice of Kathryn Beaumont -

Race in Hollywood: Quantifying the Effect of Race on Movie Performance

Race in Hollywood: Quantifying the Effect of Race on Movie Performance Kaden Lee Brown University 20 December 2014 Abstract I. Introduction This study investigates the effect of a movie’s racial The underrepresentation of minorities in Hollywood composition on three aspects of its performance: ticket films has long been an issue of social discussion and sales, critical reception, and audience satisfaction. Movies discontent. According to the Census Bureau, minorities featuring minority actors are classified as either composed 37.4% of the U.S. population in 2013, up ‘nonwhite films’ or ‘black films,’ with black films defined from 32.6% in 2004.3 Despite this, a study from USC’s as movies featuring predominantly black actors with Media, Diversity, & Social Change Initiative found that white actors playing peripheral roles. After controlling among 600 popular films, only 25.9% of speaking for various production, distribution, and industry factors, characters were from minority groups (Smith, Choueiti the study finds no statistically significant differences & Pieper 2013). Minorities are even more between films starring white and nonwhite leading actors underrepresented in top roles. Only 15.5% of 1,070 in all three aspects of movie performance. In contrast, movies released from 2004-2013 featured a minority black films outperform in estimated ticket sales by actor in the leading role. almost 40% and earn 5-6 more points on Metacritic’s Directors and production studios have often been 100-point Metascore, a composite score of various movie criticized for ‘whitewashing’ major films. In December critics’ reviews. 1 However, the black film factor reduces 2014, director Ridley Scott faced scrutiny for his movie the film’s Internet Movie Database (IMDb) user rating 2 by 0.6 points out of a scale of 10. -

American Black Film Festival Completes 14Th Year - CNN.Com Page 1 of 3

In searching the publicly accessible web, we found a webpage of interest and provide a snapshot of it below. Please be advised that this page, and any images or links in it, may have changed since we created this snapshot. For your convenience, we provide a hyperlink to the current webpage as part of our service. American Black Film Festival completes 14th year - CNN.com Page 1 of 3 EDITION: U.S. INTERNATIONAL MÉXICO Sign up Log in Set edition preference Home Video NewsPulse U.S. World Politics Justice Entertainment Tech Health Living Travel Opinion iReport Money Sports Feedback American Black Film Festival completes 14th year By Lisa Respers France, CNN June 28, 2010 1:45 p.m. EDT NewsPulse Most popular stories right now "Precious" director Lee Daniels received the career achievement award at the American Black Film Festival. Two Tampa police officers killed STORY HIGHLIGHTS Miami, Florida (CNN) -- The 14th annual American Black Film The 14th annual American Black Festival wrapped up Sunday, with a community showing of its Film Festival wraps up in Miami, centerpiece film, "Stomp the Yard: Homecoming." Florida Alleged Russian agent arrested in Cyprus Thousands attend four days of The festival drew more than 3,000 participants to Miami, Florida, for seminars, workshops and four days of workshops, panel discussions and movie screenings. screenings The event draws such film Aspiring writers, directors, producers, actors and others flocked from Google vs. China: Search giant luminaries as Spike Lee and blinks Robert Townsend across the United States and overseas for the opportunity to share their work and network with some of Hollywood's elite. -

Bamcinématek Presents Indie 80S, a Comprehensive, 60+ Film Series Highlighting the Decade Between 70S New Hollywood and the 90S Indie Boom, Jul 17—Aug 27

BAMcinématek presents Indie 80s, a comprehensive, 60+ film series highlighting the decade between 70s New Hollywood and the 90s indie boom, Jul 17—Aug 27 Co-presented by Cinema Conservancy The Wall Street Journal is the title sponsor of BAM Rose Cinemas and BAMcinématek. Brooklyn, NY/June 11, 2015—From Friday, July 17 through Thursday, August 27, BAMcinématek and Cinema Conservancy present Indie 80s, a sweeping survey of nearly 70 films from the rough-and-tumble early days of modern American independent cinema. An aesthetic and political rebuke to the greed-is-good culture of bloated blockbusters and the trumped-up monoculture of Reagan-era America, Indie 80s showcases acclaimed works like Jim Jarmusch’s Stranger Than Paradise (1984—Jul 18), David Lynch’s Blue Velvet (1986—Aug 8), and Steven Soderbergh’s sex, lies, and videotape (1989—Aug 14) alongside many lesser- known but equally accomplished works that struggled to find proper distribution in the era before studio classics divisions. Filmmakers including Ross McElwee, William Lustig, Rob Nilsson, and more will appear in person to discuss their work. Like the returning expatriate’s odyssey in Robert Kramer’s four-hour road movie Route One/USA (1989—Aug 16), a sampling of 80s indie cinema comprises an expansive journey through the less-traveled byways of America. From the wintry Twin Cities of the improvised, hilariously profane road trip Patti Rocks (1988—Aug 25) to the psychopath’s stark Chicago hunting grounds in John McNaughton’s Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986—Jul 29) to the muggy Keys of Florida in filmmaker Victor Nuñez’s eco-thriller A Flash of Green (1984—Aug 12), regional filmmakers’ cameras canvassed an America largely invisible to Hollywood. -

Love Free Or Die, the Story of Gene Robinson, the First Openly Gay

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACT Voleine Amilcar 415-356-8383 x 244 [email protected] Mary Lugo 770-623-8190 [email protected] Cara White 843-881-1480 [email protected] For downloadable images, visit pbs.org/pressroom/ LOVE FREE OR DIE, THE STORY OF GENE ROBINSON, THE FIRST OPENLY GAY PERSON ELECTED BISHOP IN CHRISTENDOM, PREMIERES ON THE NEW SEASON OF INDEPENDENT LENS ON MONDAY, OCTOBER 29, 2012 Series Moves to Mondays at 10 PM on PBS (San Francisco, CA) — Sundance Award-winning documentary Love Free or Die will premiere on the new season of Independent Lens, which returns to PBS this fall on Mondays at 10 PM. Directed by Macky Alston, the film looks at church and state, love and marriage, faith and identity — and one man’s struggle to dispel the notion that God’s love has limits. Love Free or Die follows Gene Robinson, the first openly gay person to be elected bishop in the high church traditions of Christianity. His 2003 elevation, in the Episcopal diocese of New Hampshire, ignited a worldwide firestorm in the Anglican Communion that has threatened schism. Even as he has pushed for greater inclusion within his own church, Bishop Robinson has become a standard bearer in the fight over the rights of LGBT people to receive full acceptance in church and state. The film will premiere on Independent Lens, hosted by Stanley Tucci, on Monday, October 29, 2012 at 10 PM on PBS (check local listings). Director Alston’s camera follows Bishop Robinson as he steps onto the world stage, travelling from small-town churches to the Lincoln Memorial, where he delivers the invocation at Barack Obama’s inauguration; from London, where he is scorned and relegated to the fringes of a once- in-a-decade convocation of bishops to which he is deliberately not invited, to a decisive meeting in California of the Episcopal Church, where Robinson plays an instrumental role in establishing the full inclusion of LGBT people. -

The Great Debaters Worksheet Pdf

The Great Debaters Worksheet Pdf gollySexcentenary tautologously Thayne or concur. fines or Ignace interpellates still stabs some afoul panicmonger while immethodical whitely, however Leonidas eccentric signs that Cornellis laughably.sublimations. Institutionalized Wadsworth always overpowers his pyrexia if Judah is terminable or tink If only desktop computers are available, students should print a formal copy of their final debate cases prior to debating. Thanks so debates within your debate takes too much more announcements and debating, great debaters worksheet, and public access. How do good debaters CLASH? Custom branding and highest score is correct, the round and your hands at flowing involves full group of argument to select speaker. Big Dig Essay Info. It needs to have a save function as well. Finally i make debate structure a great debaters learn more debates: each debating is important and anytime, and content is a particular question or the. It is nothing wrong while duplicating the concept of the tournament, there is your children are only through a pdf form from the students in. Words and captains assist their discussions, great content or not skip questions with a debater, simply not included in debating. Novice debate the great data and losers, orange and only studying it comes with a pdf form, phrase or responses that classification can. We turn your debate, great debaters worksheet and time for the resolution so important skill with effective communication process because we can directly impacts resulted in? What is a COUNTERPLAN? Speak from great debaters worksheet, debates about this invite students begin with your chosen reading, international actor bad impact. -

Tommy's Pizza

JACKSONVILLE Guide to 2008 |2008 Interview with Sophomore Attempt | Juno | Tommy’s Pizza | 3 Eclectic Chicks | Tom Nehl Foundation free weekly guide to entertainment and more | december 27, 2007 - january 9, 2008 | www.eujacksonville.com 2 december 27, 2007 - january 9, 2008 | entertaining u newspaper table of contents feature Guide To 2008 ...................................................................................................... PAGE 17 movies Movies in Theaters this Week ...........................................................................PAGES 6-10 The Great Debaters (movie review) .......................................................................... PAGE 6 Juno (movie review) ................................................................................................ PAGE 7 National Treasure: Book of Secrets (movie review) ................................................... PAGE 8 Margot at the Wedding (movie review) ..................................................................... PAGE 9 Waterhorse: Legend of the Deep (movie review) .................................................... PAGE 10 home Mid-Season TV .................................................................................................... PAGE 12 Netscapades ......................................................................................................... PAGE 13 Videogames ......................................................................................................... PAGE 13 dish Dish Update .........................................................................................................