Angiosperms: the Flowering Plants

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rapid Assay Replicate

Algae Analysis Report and Data Set Customer ID: 000 Tracking Code: 200014-000 Sample ID: Rapid Assay Replicate: . Customer ID: 000 Sample Date: 4/30/2020 Sample Level: Epi Job ID: 1 Station: Sample Station Sample Depth: 0 System Name: Sample Lake Site: Sample Site Preservative: Glutaraldehyde Report Notes: Sample Report Note Division: Bacillariophyta Taxa ID Genus Species Subspecies Variety Form Morph Structure Relative Concentration 1109 Diatoma tenuis . Vegetative 1.00 1000936 Lindavia intermedia . Vegetative 18.00 9123 Nitzschia palea . Vegetative 1.00 1293 Stephanodiscus niagarae . Vegetative 2.00 Summary for Division ~ Bacillariophyta (4 detail records) Sum Total Bacillariophyta 22.00 Division: Chlorophyta Taxa ID Genus Species Subspecies Variety Form Morph Structure Relative Concentration 2683 *Chlorococcaceae spp . 2-9.9 um Vegetative 1.00 spherical 2491 Schroederia judayi . Vegetative 25.00 Summary for Division ~ Chlorophyta (2 detail records) Sum Total Chlorophyta 26.00 = Identification is Uncertain 200014-000 Monday, January 18, 2021 * = Family Level Identification Phytoplankton - Rapid Assay Page 2 of 13 Division: Cryptophyta Taxa ID Genus Species Subspecies Variety Form Morph Structure Relative Concentration 3015 Cryptomonas erosa . Vegetative 15.00 3043 Rhodomonas minuta . nannoplanctica . Vegetative 2.00 Summary for Division ~ Cryptophyta (2 detail records) Sum Total Cryptophyta 17.00 Division: Cyanophyta Taxa ID Genus Species Subspecies Variety Form Morph Structure Relative Concentration 4041 Aphanizomenon flos-aquae . -

8 April 2021 Mr. Jon Kurland Assistant

8 April 2021 Mr. Jon Kurland Assistant Regional Administrator Protected Resources Division, Alaska Region National Marine Fisheries Service P.O. Box 21668 Juneau, Alaska 99082-1668 Dear Mr. Kurland: The Marine Mammal Commission (the Commission), in consultation with its Committee of Scientific Advisors on Marine Mammals, has reviewed the National Marine Fisheries Service’s (NMFS) 8 January 2021 Federal Register notice (86 Fed. Reg. 1452) revising its proposed designation of critical habitat for Arctic ringed seals (Phoca hispida hispida)1 and reopening the comment period on that proposal. The Commission offers the following comments and recommendations. Background On 28 December 2012, NMFS published a final rule listing the Arctic ringed seal as threatened under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) (77 Fed. Reg. 76706) and requesting information on physical and biological features essential to the conservation of Arctic ringed seals and on economic consequences of designating critical habitat for this species. Section 3(5)(A) of the ESA defines “critical habitat” as: (i) the specific areas within the geographical area occupied by the species, at the time it is listed in accordance with section 4 of this Act, on which are found those physical or biological features (I) essential to the conservation of the species and (II) which may require special management considerations or protection; and (ii) specific areas outside the geographical area occupied by the species at the time it is listed in accordance with the provisions of section 4 of this Act, upon a determination by the Secretary that such areas are essential for the conservation of the species. -

"Phylum" for "Division" for Groups Treated As Plants Author(S): H

Proposal (10) to Substitute the Term "Phylum" for "Division" for Groups Treated as Plants Author(s): H. C. Bold, A. Cronquist, C. Jeffrey, L. A. S. Johnson, L. Margulis, H. Merxmüller, P. H. Raven and A. L. Takhtajan Reviewed work(s): Source: Taxon, Vol. 27, No. 1 (Feb., 1978), pp. 121-122 Published by: International Association for Plant Taxonomy (IAPT) Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1220504 . Accessed: 15/08/2012 04:49 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. International Association for Plant Taxonomy (IAPT) is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Taxon. http://www.jstor.org TAXON 27 (1): 121-132 FEBRUARY 1978 NOMENCLATURE TYPIFICATION OF MICROORGANISMS: A PROPOSAL Ralph A. Lewin * & G. E. Fogg** Rules and recommendations for the typification of many kinds of microorganisms, in- cluding microscopic algae and fungi, need to be updated for a variety of reasons. Improve- ments of fixation techniques normally make it unnecessary to invoke Article 9, Note 1, which relates to "the name of a species of infraspecific taxon of Recent plants of which it is impossible to preserve a specimen..." On the other hand, more and more taxonomy is being based on electron-microscopy, biochemistry, serology or other modern techniques for which living material may be needed, and for which a herbarium sheet is generally inadequate and a drawing, or even a photomicrograph, is for various reasons unsatisfactory. -

Marine-Life Data and Analysis Team (Mdat) Technical Report on the Methods and Development of Marine-Life Data to Support Regional Ocean Planning and Management

MARINE-LIFE DATA AND ANALYSIS TEAM (MDAT) TECHNICAL REPORT ON THE METHODS AND DEVELOPMENT OF MARINE-LIFE DATA TO SUPPORT REGIONAL OCEAN PLANNING AND MANAGEMENT PBS.org NEFSC Andreas Trepte, www.photo-natur.de Authors: Corrie Curtice, Jesse Cleary, Emily Shumchenia, Patrick Halpin Prepared on behalf of The Marine-life Data and Analysis Team (MDAT): Patrick Halpin (Principal Investigator, Duke University), Earvin Balderama (Co-I, Loyola University Chicago), Jesse Cleary (Duke University), Corrie Curtice (Duke University), Michael Fogarty (Co-I, NOAA/NEFSC), Brian Kinlan† (NOAA/NCCOS), Charles Perretti (NOAA/NEFSC), Marta Ribera (TNC), Jason Roberts (Duke University), Emily Shumchenia (NROC), Arliss Winship (Co-I, NOAA/NCCOS) Date published: 24 June 2019 Project manager and point of contact: Jesse Cleary, Marine Geospatial Ecology Lab, Duke University, Durham, NC 27708 em: [email protected] ph: 919-684-3660 w: mgel.env.duke.edu Accessible from: http://seamap.env.duke.edu/models/MDAT/MDAT-Technical- Report.pdf † Deceased January 27, 2017 Marine-life Data and Analysis Team Technical Report EXECUTIVE SUMMARY In 2014, the Marine Geospatial Ecology Lab (MGEL) of Duke University began work with the Northeast Regional Ocean Council (NROC), the NOAA National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science (NCCOS), the NOAA Northeast Fisheries Science Center (NEFSC), and Loyola University Chicago, as part of the Marine-life Data and Analysis Team (MDAT), to characterize and map marine life in the Northeast region, at the request of the Northeast Regional Planning Body (NE RPB) to support the Northeast Ocean Plan. These research groups collaborated to produce “base layer” distribution products for cetacean, avian, and fish species. -

Climate Change Impacts on Net Primary Production (NPP) And

Biogeosciences, 13, 5151–5170, 2016 www.biogeosciences.net/13/5151/2016/ doi:10.5194/bg-13-5151-2016 © Author(s) 2016. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Climate change impacts on net primary production (NPP) and export production (EP) regulated by increasing stratification and phytoplankton community structure in the CMIP5 models Weiwei Fu, James T. Randerson, and J. Keith Moore Department of Earth System Science, University of California, Irvine, California, 92697, USA Correspondence to: Weiwei Fu ([email protected]) Received: 16 June 2015 – Published in Biogeosciences Discuss.: 12 August 2015 Revised: 10 July 2016 – Accepted: 3 August 2016 – Published: 16 September 2016 Abstract. We examine climate change impacts on net pri- the models. Community structure is represented simply in mary production (NPP) and export production (sinking par- the CMIP5 models, and should be expanded to better cap- ticulate flux; EP) with simulations from nine Earth sys- ture the spatial patterns and climate-driven changes in export tem models (ESMs) performed in the framework of the efficiency. fifth phase of the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP5). Global NPP and EP are reduced by the end of the century for the intense warming scenario of Representa- tive Concentration Pathway (RCP) 8.5. Relative to the 1990s, 1 Introduction NPP in the 2090s is reduced by 2–16 % and EP by 7–18 %. The models with the largest increases in stratification (and Ocean net primary production (NPP) and particulate or- largest relative declines in NPP and EP) also show the largest ganic carbon export (EP) are key elements of marine bio- positive biases in stratification for the contemporary period, geochemistry that are vulnerable to ongoing climate change suggesting overestimation of climate change impacts on NPP from rising concentrations of atmospheric CO2 and other and EP. -

A Review of Phylogenetic Hypotheses Regarding Aphodiinae (Coleoptera; Scarabaeidae)

STATE OF KNOWLEDGE OF DUNG BEETLE PHYLOGENY - a review of phylogenetic hypotheses regarding Aphodiinae (Coleoptera; Scarabaeidae) Mattias Forshage 2002 Examensarbete i biologi 20 p, Ht 2002 Department of Systematic Zoology, Evolutionary Biology Center, Uppsala University Supervisor Fredrik Ronquist Abstract: As a preparation for proper phylogenetic analysis of groups within the coprophagous clade of Scarabaeidae, an overview is presented of all the proposed suprageneric taxa in Aphodiinae. The current knowledge of the affiliations of each group is discussed based on available information on their morphology, biology, biogeography and paleontology, as well as their classification history. With this as a background an attempt is made to estimate the validity of each taxon from a cladistic perspective, suggest possibilities and point out the most important questions for further research in clarifying the phylogeny of the group. The introductory part A) is not a scientific paper but an introduction into the subject intended for the seminar along with a polemic against a fraction of the presently most active workers in the field: Dellacasa, Bordat and Dellacasa. The main part B) is the discussion of all proposed suprageneric taxa in the subfamily from a cladistic viewpoint. The current classification is found to be quite messy and unfortunately a large part of the many recent attempts to revise higher-level classification within the group do not seem to be improvements from a phylogenetic viewpoint. Most recently proposed tribes (as well as -

Points of View DIVISION MABINF Mvbb3cebbatb8

Points of View SEFB.1^ Misuse of Generic Names of Shrimp (Family Penaeidae) DIVISION MABINF mVBB3CEBBATB8 CARDED SEP 161959 Reprinted from SYSTEMATIC ZOOLOGY Volume 6, Number 2, June 1957 Points of View Misuse of Generic Names of Shrimp (Family Penaeidae) Misuse of names of the penaeid shrimp of the ligature oe may have been a print- has been going on for well over a hundred er's error, for in many of the older fonts years. The matter is of some importance the a in the ae ligature was script-like and because interest in these shrimp, both therefore easily confused with the oe. zoologically and commercially, is increas- Smith (1871, not 1869 as is commonly ing greatly every year and use of the stated) used Peneus and in the same pa- Latin names in general papers and statis- per described the genus Xiphopeneus. tical reports is increasing commensu- Later when he realized that Peneus was rately. Most authors are non-taxonomists wrong and took up Fabricius' original and follow rather faithfully the erroneous spelling, he recognized that Xiphopeneus spellings of reputedly authoritative works. would have to stand (Smith 1882, 1886). Some of these spellings are wrong for the The doyen of American carcinologists, same reasons other words are sometimes Waldo L. Schmitt, apparently had a simi- spelled wrong. Others are based upon lar experience, for in 1926 he used Peneus, misconceptions. The latter are the more citing Weber as the original authority, but important and are the only ones treated in turned to Penaeus later (Schmitt, 1926, these remarks. -

Phylogeny and Geological History of the Cynipoid Wasps (Hymenoptera: Cynipoidea) Zhiwei Liu Eastern Illinois University, [email protected]

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Faculty Research & Creative Activity Biological Sciences January 2007 Phylogeny and Geological History of the Cynipoid Wasps (Hymenoptera: Cynipoidea) Zhiwei Liu Eastern Illinois University, [email protected] Michael S. Engel University of Kansas, Lawrence David A. Grimaldi American Museum of Natural History Follow this and additional works at: http://thekeep.eiu.edu/bio_fac Part of the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Liu, Zhiwei; Engel, Michael S.; and Grimaldi, David A., "Phylogeny and Geological History of the Cynipoid Wasps (Hymenoptera: Cynipoidea)" (2007). Faculty Research & Creative Activity. 197. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/bio_fac/197 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Biological Sciences at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Research & Creative Activity by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST AT 79TH STREET, NEW YORK, NY 10024 Number 3583, 48 pp., 27 figures, 4 tables September 6, 2007 Phylogeny and Geological History of the Cynipoid Wasps (Hymenoptera: Cynipoidea) ZHIWEI LIU,1 MICHAEL S. ENGEL,2 AND DAVID A. GRIMALDI3 CONTENTS Abstract . ........................................................... 1 Introduction . ....................................................... 2 Systematic Paleontology . ............................................... 3 Superfamily Cynipoidea Latreille . ....................................... 3 -

Classification of Plants

Classification of Plants Plants are classified in several different ways, and the further away from the garden we get, the more the name indicates a plant's relationship to other plants, and tells us about its place in the plant world rather than in the garden. Usually, only the Family, Genus and species are of concern to the gardener, but we sometimes include subspecies, variety or cultivar to identify a particular plant. Starting from the top, the highest category, plants have traditionally been classified as follows. Each group has the characteristics of the level above it, but has some distinguishing features. The further down the scale you go, the more minor the differences become, until you end up with a classification which applies to only one plant. Written convention indicated with underlined text KINGDOM Plant or animal DIVISION (PHYLLUM) CLASS Angiospermae (Angiosperms) Plants which produce flowers Gymnospermae (Gymnosperms) Plants which don't produce flowers SUBCLASS Dicotyledonae (Dicotyledons, Dicots) Plants with two seed leaves Monocotyledonae (Monocotyledons, Monocots) ‐ Plants with one seed leaf SUPERORDER A group of related Plant Families, classified in the order in which they are thought to have developed their differences from a common ancestor. There are six Superorders in the Dicotyledonae (Magnoliidae, Hamamelidae, Caryophyllidae, Dilleniidae, Rosidae, Asteridae), and four Superorders in the Monocotyledonae (Alismatidae, Commelinidae, Arecidae, Liliidae). The names of the Superorders end in ‐idae ORDER ‐ Each Superorder is further divided into several Orders. The names of the Orders end in ‐ales FAMILY ‐ Each Order is divided into Families. These are plants with many botanical features in common, and is the highest classification normally used. -

Anatomy and Go Fish! Background

Anatomy and Go Fish! Background Introduction It is important to properly identify fi sh for many reasons: to follow the rules and regulations, for protection against sharp teeth or protruding spines, for the safety of the fi sh, and for consumption or eating purposes. When identifying fi sh, scientists and anglers use specifi c vocabulary to describe external or outside body parts. These body parts are common to most fi sh. The difference in the body parts is what helps distinguish one fi sh from another, while their similarities are used to classify them into groups. There are approximately 29,000 fi sh species in the world. In order to identify each type of fi sh, scientists have grouped them according to their outside body parts, specifi cally the number and location of fi ns, and body shape. Classifi cation Using a system of classifi cation, scientists arrange all organisms into groups based on their similarities. The fi rst system of classifi cation was proposed in 1753 by Carolus Linnaeus. Linnaeus believed that each organism should have a binomial name, genus and species, with species being the smallest organization unit of life. Using Linnaeus’ system as a guide, scientists created a hierarchical system known as taxonomic classifi cation, in which organisms are classifi ed into groups based on their similarities. This hierarchical system moves from largest and most general to smallest and most specifi c: kingdom, phylum, class, order, family, genus, and species. {See Figure 1. Taxonomic Classifi cation Pyramid}. For example, fi sh belong to the kingdom Animalia, the phylum Chordata, and from there are grouped more specifi cally into several classes, orders, families, and thousands of genus and species. -

The Ferns and Their Relatives (Lycophytes)

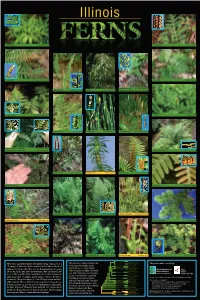

N M D R maidenhair fern Adiantum pedatum sensitive fern Onoclea sensibilis N D N N D D Christmas fern Polystichum acrostichoides bracken fern Pteridium aquilinum N D P P rattlesnake fern (top) Botrychium virginianum ebony spleenwort Asplenium platyneuron walking fern Asplenium rhizophyllum bronze grapefern (bottom) B. dissectum v. obliquum N N D D N N N R D D broad beech fern Phegopteris hexagonoptera royal fern Osmunda regalis N D N D common woodsia Woodsia obtusa scouring rush Equisetum hyemale adder’s tongue fern Ophioglossum vulgatum P P P P N D M R spinulose wood fern (left & inset) Dryopteris carthusiana marginal shield fern (right & inset) Dryopteris marginalis narrow-leaved glade fern Diplazium pycnocarpon M R N N D D purple cliff brake Pellaea atropurpurea shining fir moss Huperzia lucidula cinnamon fern Osmunda cinnamomea M R N M D R Appalachian filmy fern Trichomanes boschianum rock polypody Polypodium virginianum T N J D eastern marsh fern Thelypteris palustris silvery glade fern Deparia acrostichoides southern running pine Diphasiastrum digitatum T N J D T T black-footed quillwort Isoëtes melanopoda J Mexican mosquito fern Azolla mexicana J M R N N P P D D northern lady fern Athyrium felix-femina slender lip fern Cheilanthes feei net-veined chain fern Woodwardia areolata meadow spike moss Selaginella apoda water clover Marsilea quadrifolia Polypodiaceae Polypodium virginanum Dryopteris carthusiana he ferns and their relatives (lycophytes) living today give us a is tree shows a current concept of the Dryopteridaceae Dryopteris marginalis is poster made possible by: { Polystichum acrostichoides T evolutionary relationships among Onocleaceae Onoclea sensibilis glimpse of what the earth’s vegetation looked like hundreds of Blechnaceae Woodwardia areolata Illinois fern ( green ) and lycophyte Thelypteridaceae Phegopteris hexagonoptera millions of years ago when they were the dominant plants. -

Undergraduate Program

Department of Botany and Plant Pathology Undergraduate Program Botany and Plant Pathology are concerned with the study of plants at all levels of biological organizaton, from molecular and cellular processes to the global ecosystem. This breadth of feld refects the wide range of issues and problems that confront plant biologists. In additon to addressing fundamental questons in plant biology, plant scientsts in the 21st century will be called upon to provide informaton useful for producing food, fber, and medicine for an increasing populaton, and for increasing our understanding of the diversity of plant and ecological systems and their interactons with humans. Students studying botany and plant pathology at OSU receive the basic science background necessary for such contributons, and may choose to focus in a partcular area within plant science. The undergraduate program in the Department of Botany and Plant Pathology is designed for students who wish to receive a B.S. degree in Botany and for students pursuing degrees in other felds that require a knowledge of plant biology. For example, students who have an undergraduate major in biology or environmental science may wish to emphasize botany courses in their upper division course work, or add a botany minor. Completon of the undergraduate curriculum in botany can qualify students for graduate work in various areas of plant biology and plant pathology, and for positons in state and federal agencies and industries concerned with plants and their products. Prospectve botany majors should obtain a strong background in the biological and physical sciences at the high school level. Specifcally recommended are a minimum of three years of high school mathematcs, including algebra, geometry, and some exposure to trigonometry; one year of physics; and courses designed to develop computer and writng skills.