“The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” STUDY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Link to Coleridge Poems

1 Poems for S. T. Coleridge Edward Sanders 1. Coleridge won a medal his 1st year in college (Cambridge 1792) for a “Sapphic Ode on the Slave Trade” 2. Pantisocracy Sam Coleridge and Bob Southey conceived of Pantisocracy in 1794 just five years after the beautiful tearing down of the Bastille twelve couples would found an intentional community on the Susquehanna River which flows from upstate New York ambling for hundreds of miles down thru Pennsylvania & emptying into the Chesapeake Bay The plan was to work maybe 2-3 hours a day with sharing of chores Each couple had to come up with 125 pounds So Southey & Coleridge strove to earn their shares through writing C. wrote to Southey 9-1-94 2 that Joseph Priestly might join the Pantisocrats in America The scientist-philosopher had set up a “Constitution Society” to advocate reform of Parliament inaugurated on Bastille Day 1791 Then “urged on by local Tories” a mob attacked & burned Priestly’s books, manuscripts laboratory & home so that he ultimately fled to the USA. 3. Worry-Scurry for Expenses In Coleridge from his earliest days worry-scurry for expenses relying on say a play about Robespierre writ w/ Southey in ’94 (around the time Robe’ was guillotined) to pay for their share of Pantisocracy on the Susquehanna & thereafter always reliant on Angels & the G. of S. Generosity of Supporters & brilliance of mouth all the way thru the hoary hundreds 3 4. Coleridge & Southey brothers-in-law —the Fricker sisters, Edith & Sarah Coleridge & Sarah Fricker married 10-4-95 son Hartley born September 19, 1996 short-lived Berkeley in May 1998 Derwent Coleridge on September 14, 1800 & Sara on Dec 23, ’02 5. -

1772-1834) the Rime of the Ancient Mariner (Text of 1834

Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772-1834) The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (text of 1834) Argument How a Ship having passed the Line was driven by storms to the cold Country towards the South Pole; and how from thence she made her course to the tropical Latitude of the Great Pacific Ocean; and of the strange things that befell; and in what manner the Ancyent Marinere came back to his own Country. PART I M An ancient Mariner meeteth three Gallants bidden to a wedding-feast, and detaineth one. It is an ancient Mariner, 01 And he stoppeth one of three. 'By thy long grey beard and glittering eye, Now wherefore stopp'st thou me? The Bridegroom's doors are opened wide, 05 And I am next of kin; The guests are met, the feast is set: May'st hear the merry din.' He holds him with his skinny hand, 09 'There was a ship,' quoth he. 'Hold off! unhand me, grey-beard loon!' Eftsoons his hand dropt he. M The Wedding-Guest is spellbound by the eye of the old seafaring man, and constrained to hear his tale. He holds him with his glittering eye-- 13 The Wedding-Guest stood still, And listens like a three years' child: The Mariner hath his will. The Wedding-Guest sat on a stone: 17 He cannot choose but hear; And thus spake on that ancient man, The bright-eyed Mariner. 'The ship was cheered, the harbour cleared, 21 Merrily did we drop M The Mariner tells how the ship sailed southward with a good wind and fair weather, till it reached the line. -

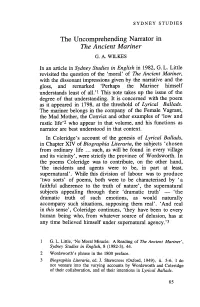

The Uncomprehending Narrator in the Ancient Mariner G

SYDNEY STUDIES The Uncomprehending Narrator in The Ancient Mariner G. A. WILKES In an article in Sydney Studies in English in 1982, G. L. Little revisited the question of the 'moral' of The Ancient Mariner, with the dissonant impressions given by the narrative and the gloss, and remarked 'Perhaps the Mariner himself understands least of all.' 1 This note takes up the issue of the degree of that understanding. It is concerned with the poem as it appeared in 1798, at the threshold of Lyrical Ballads. The mariner belongs in the company of the Female Vagrant, the Mad Mother, the Convict and other examples of 'low and rustic life'2 who appear in that volume, and his functions as narrator are best understood in that context. In Coleridge's account of the genesis of Lyrical Ballads, in Chapter XIV of Biographia Literaria, the subjects 'chosen from ordinary life ... such, as will be found in every village and its vicinity', were strictly the province of Wordsworth. In the poems Coleridge was to contribute, on the other hand, 'the incidents and agents were to be, in part at least, supernatural'. While this division of labour was to produce 'two sorts' of poems, both were to be characterised by 'a faithful adherence to the truth of nature', the supernatural subjects appealing through their 'dramatic truth' - 'the dramatic truth of such emotions, as would naturally accompany such situations, supposing them real'. 'And real in this sense', Coleridge continues, 'they have been to every human being who, from whatever source of delusion, has at any time believed himself under supernatural agency.'3 G. -

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, June 2017, Vol. 7, No. 6, 675-678 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2017.06.006 D DAVID PUBLISHING The Images in The Rime of the Ancient Mariner XING Fang-fang, HUA Yan University of Shanghai for Science and Technology, Shanghai, China The paper mainly talks about the background of S. T. Coleridge and the images of The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. As for the images, the wind, the albatross and the snake will be thoroughly discussed. There are many different images which also have different meanings and connotations in the context. What’s more, the poem expresses the theme of the metabolic relationships between men and nature: harmony, conflict or compromise. Keywords:The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, S. T. Coleridge, images Introduction Samuel Taylor Coleridge is one of the most significant poets and critics in English literature. Generally, his poems are mainly composed of two parts: one is using common language to depict common things and ordinary people; the other is using unique imagination to describe supernatural things. The Rime of the Ancient Mariner belongs to the second group (Coleridge, 2004). It is one of his famous poems, which helps him win lots of fame and makes him firmly stand in literature field. Meanwhile, this poem is also Coleridge’s major contribution to the Lyrical Ballads. Some critics blame Coleridge for his lack of morals in his poems. But actually, this poem contains lots of morals according to Coleridge. Coleridge succeeds in exploring the theme of sin by his rich imagination and the depicting supernatural. -

Coleridge As the Marinerâ•Fldisconnection and Redemption In

Taylor University Pillars at Taylor University Making Literature Conference 2019 Conference Feb 28th, 11:00 AM Coleridge as the Mariner—Disconnection and Redemption in Comparing ‘Dejection: An Ode’ and ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’ Tali Valentine Taylor University Follow this and additional works at: https://pillars.taylor.edu/makingliterature Part of the Creative Writing Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, and the Higher Education Commons Valentine, Tali, "Coleridge as the Mariner—Disconnection and Redemption in Comparing ‘Dejection: An Ode’ and ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’" (2019). Making Literature Conference. 2. https://pillars.taylor.edu/makingliterature/2019conference/ce1/2 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Campus Events at Pillars at Taylor University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Making Literature Conference by an authorized administrator of Pillars at Taylor University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Valentine 1 Natalia Valentine Dr. Emma Plaskitt Literature 1740-1832 9 November 2018 Coleridge as the Mariner – Disconnection and Redemption in Comparing Dejection: An Ode (1802) and The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798) Both Dejection: An Ode (1802) and The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798) interact with disconnection, alienation, and depression as they were evident in the ebb and flow of Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s life. Written four years apart from one another, the journey of both poems explains the nature, source, and consequences of such isolation; in other words, Coleridge’s expression of, “the evils of separation and finiteness,” which was to Romantic thinking was the, “Radical affliction of the human condition” (Abrams 183). -

The Poems of Samuel Taylor Coleridge By

The Poems of Samuel Taylor Coleridge by SAMUEL TAYLOR COLERIDGE 1787-1833 DjVu Editions E-books © 2001, Global Language Resources, Inc. Coleridge: Poems Table of Contents Easter Holidays . 1 Dura Navis . 2 Nil Pejus est Caelibe Vitæ . 4 Sonnet to the Autumnal Moon . 5 Anthem for the Children of Christ’s Hospital . 6 Julia . 7 Quae Nocent Docent . 8 The Nose . 9 To the Muse . 11 Destruction of the Bastile . 12 Life . 14 Progress of Vice . 15 Monody on the Death of Chatterton . 16 An Invocation . 19 Anna and Harland . 20 To the Evening Star . 21 Pain . 22 On a Lady Weeping: Imitation from the Latin of Nicolaus Archius . 23 Monody on a Tea-kettle . 24 Genevieve . 26 On Receiving an Account that his Only Sister’s Death was Inevitable . 27 On Seeing a Youth Affectionately Welcomed by a Sister . 28 A Mathematical Problem . 29 Honour . 32 On Imitation . 34 Inside the Coach . 35 Devonshire Roads . 36 Music . 37 Sonnet: On Quitting School for College . 38 Absence: A Farewell Ode on Quitting School for Jesus College, Cambridge . 39 Happiness . 40 A Wish: Written in Jesus Wood, Feb. 10, 1792 . 43 An Ode in the Manner of Anacreon . 44 To Disappointment . 45 A Fragment Found in a Lecture-Room . 46 Ode . 47 A Lover’s Complaint to his Mistress . 49 With Fielding’s ‘‘Amelia’’ . 50 Written After a Walk Before Supper . 51 Imitated from Ossian . 52 The Complaint of Ninathóma: From the same . 53 Songs of the Pixies . 54 The Rose . 57 - i - Kisses . 58 The Gentle Look . 59 Sonnet: To the River Otter . -

Academic Forum 32 (2014–15)

Academic Forum 32 (2014–15) Credits We appreciate the efforts of Dr. Brett Serviss, who oversaw the project which was the source of the data used in this paper. Also, we appreciate the Ellis College Planning and Advisory Committee who funded the presentation of this paper at the regional Oklahoma-Arkansas Mathematical Association of America meeting. References Arkansas Vascular Flora Committee (AVFC). 2006. Checklist of the Vascular Plants of Arkansas. Arkansas Vascular Flora Committee, Fayetteville, Arkansas. A. Cannon et al., STAT2, Building Models for a World of Data, Ed. (Freeman, New York, NY, 2013) Biographical Sketches Michael Lloyd graduated cum laude and in the honors program in Chemical Engineering with a B.S. in 1984. He accepted a position at Henderson State University in 1993 shortly after earning his Ph.D. in Mathematics (Probability Theory) from Kansas State University. He has presented papers at meetings of the Academy of Economics and Finance, the American Mathematical Society, the Arkansas Conference on Teaching, and the Southwest Arkansas Council of Teachers of Mathematics. He has been an active member of the Mathematical Association of America since 1993, earned 18 hours in computer science, and has been an Advanced Placement statistics consultant since 2002. Jonathan Eagle received his B.S. in Biology, minoring in chemistry and statistics, in 2015 from Henderson State University. Graduating cum laude as member of Honors College and the McNair Scholar Program, he was recognized as the Outstanding Graduating Senior in the Biology Department. He plans to continue his education at the graduate level in the area of biomolecular sciences. -

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, 1795, London, National Portrait Gallery

Peter Vandyke, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, 1795, London, National Portrait Gallery. Samuel Taylor Coleridge Compact Performer - Culture & Literature Marina Spiazzi, Marina Tavella, Margaret Layton © 2015 Samuel Taylor Coleridge 1. Life • Born in Devonshire in 1772. Christ’s Hospital School • Studied at Christ’s Hospital School in London, and then in Cambridge, but never graduated. • Influenced by French revolutionary ideals. • After the disillusionment with the French Revolution, he planned a utopian society, Pantisocracy, in Pennsylvania, based on equal rights and without private property. This project failed. • Fruitful artistic collaboration with the poet and friend William Wordsworth in the 1797-1799 period. • Died in 1834. Compact Performer - Culture & Literature Samuel Taylor Coleridge 2. Main works 1798 The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, the first poem of the collection Lyrical Ballads •1816 the dreamlike poem Kubla Khan, composed under the influence of opium •1817 Biographia Literaria, a classic text of literary criticism and autobiography. Coleridge also held lectures about Hand-written page from literature and journalism. He started Kubla Khan Shakespearian criticism. Compact Performer - Culture & Literature Samuel Taylor Coleridge 3. Coleridge and Wordsworth Wordsworth’s poetry Coleridge’s poetry Content • Things from ordinary • Supernatural life characters and events Aim • To give these ordinary • To make extraordinary things the charm of novelty events credible (so and show the moral values of supernatural and realistic simple life. elements coexist) Style • The simple language of • Archaic language rich in common men sound devices Main Relationship between man and The creative power of interest nature; imagination as a imagination means of knowledge Compact Performer - Culture & Literature Samuel Taylor Coleridge 4. -

Romantic Elements and the Sublime in S. T. Coleridge's "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner"

Romantic Elements and the Sublime in S. T. Coleridge's "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner" Pavić, Dora Undergraduate thesis / Završni rad 2017 Degree Grantor / Ustanova koja je dodijelila akademski / stručni stupanj: Josip Juraj Strossmayer University of Osijek, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences / Sveučilište Josipa Jurja Strossmayera u Osijeku, Filozofski fakultet Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:142:996552 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-09-25 Repository / Repozitorij: FFOS-repository - Repository of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Osijek Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Studij: Dvopredmetni sveučilišni preddiplomski studij engleskoga jezika i književnosti i filozofije Dora Pavić Elementi romantizma i uzvišenoga u S. T. Coleridgeovoj “Pjesmi o starom mornaru“ Završni rad doc. dr. sc. Ljubica Matek Osijek, 2017. Sveučilište J.J. Strossmayera u Osijeku Filozofski fakultet Osijek Odsjek za engleski jezik i književnost Studij: Dvopredmetni sveučilišni preddiplomski studij engleskoga jezika i književnosti i filozofije Dora Pavić Elementi romantizma i uzvišenoga u S. T. Coleridgeovoj “Pjesmi o starom mornaru“ Završni rad Znanstveno područje: humanističke znanosti Znanstveno polje: filologija Znanstvena grana: anglistika doc. dr. sc. Ljubica Matek Osijek, 2017. J.J. Strossmayer University of Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Study Programme: Double Major BA Study Programme in English Language and Literature and Philosophy Dora Pavić Romantic Elements and the Sublime in S. T. Coleridge's “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” Bachelor's Thesis Supervisor: Ljubica Matek, PhD., Assistant Professor Osijek, 2017 J.J. Strossmayer University of Osijek Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Department of English Study Programme: Double Major BA Study Programme in English Language and Literature and Philosophy Dora Pavić Romantic Elements and the Sublime in S. -

Coleridge's the Rime of the Ancient Mariner

ARTICLE LUKE STRONGMAN Captain Cook’s Voyages and Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner The debt that Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s romantic ballad The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1798) owes to George Shelvocke’s A Voyage Around the World By Way of the Great South Sea (1726) was first claimed by William Wordsworth and has been well documented by Fruman,1 Holmes,2 Hill,3 Lamb4 and others. Further, the influence of Cook’sVoyage towards the South Pole and round the world performed in His Majesty’s ships the Resolution and Adventure in the years 1772, 1773, 1774 & 1775 has been suggested by Moorehead5 and Smith.6 This article posits that the familiar four-step account of the ballad’s creation – that the idea arose through a suggestion to Coleridge from William Wordsworth following the relation to Coleridge of an unusual dream of his friend, John Cruikshank, and was inspired by Coleridge’s reading of the journal of George Shelvocke and the conversational influence of William Wales (an astronomer and meteorologist on board Cook’s Resolution in 1772) upon Coleridge as a schoolboy – is in fact a partial account. Cook and Banks’ journals and the paintings of William Hodges and George Forster deserve greater credit as sources of inspiration. In the original 1789 version of Coleridge’s ballad the figure of the mariner gains definition from Coleridge’s familiarity with the journals of Captain Cook’s voyages. Coleridge’s familiarity with the South Pacific journals of discovery, as well as the European literary influences more accustomed to enlightened British readers of the early nineteenth century, such as Erasmus Darwin, John Dryden, and William Wordsworth, infused Coleridge’s writings with an awareness of the journeying towards the icy poles of both southern and northern hemispheres. -

Coleridgeâ•Žs Albatross and the Impulse to Seabird Conservation

Kunapipi Volume 29 Issue 2 Article 5 2007 Coleridge’s albatross and the impulse to seabird conservation Graham Barwell Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Barwell, Graham, Coleridge’s albatross and the impulse to seabird conservation, Kunapipi, 29(2), 2007. Available at:https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol29/iss2/5 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Coleridge’s albatross and the impulse to seabird conservation Abstract oleridge was a regular companion. Emigrants’ diaries and journals rarely failed to describe one particular landmark experience: the first sighting of the albatross, followed by attempts to kill or capture a specimen, in the style of the Ancient Mariner. ‘Who could doubt their supernatural attributes? Certainly not a spirit-chilled landswoman, with Coleridge’s magic legend perpetually repeating itself to her’, wrote 27-year-old Luisa [sic] Meredith, arriving in Sydney in 1839. (Lyons 13)1 This journal article is available in Kunapipi: https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol29/iss2/5 22 GRAHAM Barwell coleridge’s Albatross and the Impulse to Seabird conservation On the long sea journey to Australia, … coleridge was a regular companion. Emigrants’ diaries and journals rarely failed to describe one particular landmark experience: the first sighting of the albatross, followed by attempts to kill or capture a specimen, in the style of the Ancient Mariner. ‘Who could doubt their supernatural attributes? Certainly not a spirit-chilled landswoman, with coleridge’s magic legend perpetually repeating itself to her’, wrote 27-year-old Luisa [sic] Meredith, arriving in Sydney in 1839. -

Revolutions in Thought and Action

‗THE BALANCE OR RECONCILIATION OF OPPOSITE OR DISCORDANT QUALITIES‘: POLITICAL TENSIONS AND RELIGIOUS TRANSITIONS IN THE WORKS OF SAMUEL TAYLOR COLERIDGE KATHRYN ELIZABETH BEAVERS A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Greenwich for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2011 DECLARATION I certify that this work has not been accepted in substance for any degree, and is not concurrently being submitted for any degree other than that of PhD being studied at the University of Greenwich. I also declare that this work is the result of my own investigations except where otherwise identified by references and that I have not plagiarised another‘s work. Student: 31 May 2011 Supervisor: 31 May 2011 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people who have supported me in various ways over the course of my PhD, whom I would like to take a moment to thank here. Particularly, I would like to thank my family for their continual support and encouragement: Jon, for enduring my thesis-related mood-swings and crises over the last seven years, whilst also simultaneously handling his own; Mum and Dad, for their sustained financial and emotional support; Granddad, for his enthusiastic support in the early stages of my PhD; Sarah and Adam, Mike and Chris, for their sustained interest and encouragement, especially valued at times when the going was rough; and Jan and Gordon, for their continued and sustained interest in many areas of my life, in addition to my thesis. I would particularly like to express my gratitude to Gordon for his sound advice, and constructive criticism and suggestions, as well as his willingness to transfer his interest and abilities from aeronautical engineering to Romantic poetry.