1772-1834) the Rime of the Ancient Mariner (Text of 1834

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sight & Sound Films of 2007

Sight & Sound Films of 2007 Each year we ask a selection of our contributors - reviewers and critics from around the world - for their five films of the year. It's a very loosely policed subjective selection, based on films the writer has seen and enjoyed that year, and we don't deny them the choice of films that haven't yet reached the UK. And we don't give them much time to ponder, either - just about a week. So below you'll find the familiar and the obscure, the new and the old. From this we put together the top ten you see here. What distinguishes this particular list is that it's been drawn up from one of the best years for all-round quality I can remember. 2007 has seen some extraordinary films. So all of the films in the ten are must-sees and so are many more. Enjoy. - Nick James, Editor. 1 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days (Cristian Mungiu) 2 Inland Empire (David Lynch) 3 Zodiac (David Fincher) = 4 I’m Not There (Todd Haynes) The Lives of Others (Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck) 6 Silent Light (Carlos Reygadas) = 7 The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (Andrew Dominik) Syndromes and a Century (Apichatpong Weerasethakul) No Country for Old Men (Ethan and Joel Coen) Eastern Promises (David Cronenberg) 1 Table of Contents – alphabetical by critic Gilbert Adair (Critic and author, UK)............................................................................................4 Kaleem Aftab (Critic, The Independent, UK)...............................................................................4 Geoff Andrew (Critic -

Overview of Programs and Exhibitions, Late May–June 2019

CALENDAR ADVISORY OVERVIEW OF PROGRAMS AND EXHIBITIONS, LATE MAY–JUNE 2019 Please see below for major screening series, highlighted events, and current exhibitions. Additional programs will be added as confirmed. SCREENING SERIES Panorama Europe Film Festival THROUGH MAY 19, 2019 The eleventh edition of the annual festival of new films from Europe, co-presented by MoMI and the European Union National Institutes of Culture (EUNIC), features seventeen films, including nine directed by women. Upcoming films include: Baikonur, Earth from Italian director Andrea Sorini, who will appear in person; Light as Feathers, from Dutch writer/director Rosanne Pel; Several Conversations About a Very Tall Girl, considered the first Romanian film to feature a lesbian love story, with director Bogdan Theodor Olteanu appearing in person; Babis Makridis’s Pity, which was co-written with Yorgos Lanthimos’s frequent writing partner Efthimis Filippou; from Hungary, One Day (Egy Nap), with director Zsófia Szilágyi in person; and Salomé Lamas’s acclaimed Extinction. Press Release | Schedule & Tickets See It Big! Action THROUGH JULY 7 See It Big! Action offers up favorites of the action-film genre, highlighting work from some of the form's greatest practitioners, including John Woo, Michael Mann, Steven Spielberg, Akira Kurosawa, Kathryn Bigelow, Jackie Chan, and much more. Upcoming: a Memorial Day weekend marathon of all six Mission: Impossible films; Police Story, 48 Hrs., Heat, Miami Vice, Big Trouble in Little China, Hard Boiled, Face/Off, Die Hard, Death Proof, Hooper, Point Break, Haywire, Three the Hard Way, Coffy, and Set It Off. See It Big! is the Museum’s signature big-screen series, co-programmed by Curator of Film Eric Hynes and Reverse Shot editors Jeff Reichert and Michael Koresky. -

Phoenix Films 1999-2019/20 Sorted by Film Title 10

Phoenix Films 1999-2019/20 Sorted by Film Title Film Date Rating(%) 2046 1-Feb-2006 68 120BPM (Beats Per Minute) 24-Oct-2018 75 3 Coeurs 14-Jun-2017 64 35 Shots of Rum 13-Jan-2010 65 45 Years 20-Apr-2016 83 5 x 2 3-May-2006 65 A Bout de Souffle 23-May-2001 60 A Clockwork Orange 8-Nov-2000 81 A Fantastic Woman 3-Oct-2018 84 A Farewell to Arms 19-Nov-2014 70 A Highjacking 22-Jan-2014 92 A Late Quartet 15-Jan-2014 86 A Man Called Ove 8-Nov-2017 90 A Matter of Life and Death 7-Mar-2001 80 A One and A Two 23-Oct-2001 79 A Prairie Home Companion 19-Dec-2007 79 A Private War 15-May-2019 94 A Room and a Half 30-Mar-2011 75 A Royal Affair 3-Oct-2012 92 A Separation 21-Mar-2012 85 A Simple Life 8-May-2013 86 A Single Man 6-Oct-2010 79 A United Kingdom 22-Nov-2017 90 A Very Long Engagement 8-Jun-2005 80 A War 15-Feb-2017 91 A White Ribbon 21-Apr-2010 75 Abouna 3-Dec-2003 75 About Elly 26-Mar-2014 78 Accident 22-May-2002 72 After Love 14-Feb-2018 76 After the Storm 25-Oct-2017 77 After the Wedding 31-Oct-2007 86 Alice et Martin 10-May-2000 All About My Mother 11-Oct-2000 84 All the Wild Horses 22-May-2019 88 Almanya: Welcome To Germany 19-Oct-2016 88 Amal 14-Apr-2010 91 American Beauty 18-Oct-2000 83 American Honey 17-May-2017 67 American Splendor 9-Mar-2005 78 Amores Perros 7-Nov-2001 85 Amour 1-May-2013 85 Amy 8-Feb-2017 90 An Autumn Afternoon 2-Mar-2016 66 An Education 5-May-2010 86 Anna Karenina 17-Apr-2013 82 Another Year 2-Mar-2011 86 Apocalypse Now Redux 30-Jan-2002 77 Apollo 11 20-Nov-2019 95 Apostasy 6-Mar-2019 82 Aquarius 31-Jan-2018 73 -

Matthew Barney's

MAY 13 GAZETTE 20■ Vol. 41, No. 5 Cycle Matthew Barney’s CREMASTER CREMASTER 1, May 3, 11, 14 ALSO: FREE SCHEDULE ■ NOT FOR SALE ■ For more information, ASIAN AMERICAN SHOWCASE visit us online at: www.siskelfilmcenter.org $11 General Admission, $7 Students, $6 Members ■ To receive weekly updates and special offers, join our FOLLOW US! Join our email list email list at www.siskelfilmcenter.org at www.siskelfilmcenter.org ROGER EBERT, 1942-2013 Roger Ebert was one-of-a-kind. He loved He took dialogue about the movies he loved movies so much that he wanted everyone else global, yet another way Roger found to fold to love them too. This love was at the very others into film culture through his infectious core of his work, and he brought the rewards enthusiasm. and joy of thinking about movies and talking Roger’s love for his beloved wife Chaz and debating about movies to millions of was a cornerstone of his life. Roger and Chaz people around the world. This is his legacy— were long the royal couple of any film festival. he made movies matter in a new way. He was never happier than when she was at Roger was as generous in his criticism as his side. he was astute. His championing of American We at the Gene Siskel Film Center independents and other young filmmakers mourn along with Roger’s readers is well known. He often used the power of everywhere. Our deepest sympathy goes to his fame to focus attention on new talent; a heroic Chaz; to all their extended family; review from Roger gave a welcome boost to to Roger’s longtime Sun-Times editor Laura many a young career. -

Introduction 1 Mimesis and Film Languages

Notes Introduction 1. The English translation is that provided in the subtitles to the UK Region 2 DVD release of the film. 2. The rewarding of Christoph Waltz for his polyglot performance as Hans Landa at the 2010 Academy Awards recalls other Oscar- winning multilin- gual performances such as those by Robert de Niro in The Godfather Part II (Coppola, 1974) and Meryl Streep in Sophie’s Choice (Pakula, 1982). 3. T h is u nder st a nd i ng of f i l m go es bac k to t he era of si lent f i l m, to D.W. Gr i f f it h’s famous affirmation of film as the universal language. For a useful account of the semiotic understanding of film as language, see Monaco (2000: 152–227). 4. I speak here of film and not of television for the sake of convenience only. This is not to undervalue the relevance of these questions to television, and indeed vice versa. The large volume of studies in existence on the audiovisual translation of television texts attests to the applicability of these issues to television too. From a mimetic standpoint, television addresses many of the same issues of language representation. Although the bulk of the exempli- fication in this study will be drawn from the cinema, reference will also be made where applicable to television usage. 1 Mimesis and Film Languages 1. There are, of course, examples of ‘intralingual’ translation where films are post-synchronised with more easily comprehensible accents (e.g. Mad Max for the American market). -

Link to Coleridge Poems

1 Poems for S. T. Coleridge Edward Sanders 1. Coleridge won a medal his 1st year in college (Cambridge 1792) for a “Sapphic Ode on the Slave Trade” 2. Pantisocracy Sam Coleridge and Bob Southey conceived of Pantisocracy in 1794 just five years after the beautiful tearing down of the Bastille twelve couples would found an intentional community on the Susquehanna River which flows from upstate New York ambling for hundreds of miles down thru Pennsylvania & emptying into the Chesapeake Bay The plan was to work maybe 2-3 hours a day with sharing of chores Each couple had to come up with 125 pounds So Southey & Coleridge strove to earn their shares through writing C. wrote to Southey 9-1-94 2 that Joseph Priestly might join the Pantisocrats in America The scientist-philosopher had set up a “Constitution Society” to advocate reform of Parliament inaugurated on Bastille Day 1791 Then “urged on by local Tories” a mob attacked & burned Priestly’s books, manuscripts laboratory & home so that he ultimately fled to the USA. 3. Worry-Scurry for Expenses In Coleridge from his earliest days worry-scurry for expenses relying on say a play about Robespierre writ w/ Southey in ’94 (around the time Robe’ was guillotined) to pay for their share of Pantisocracy on the Susquehanna & thereafter always reliant on Angels & the G. of S. Generosity of Supporters & brilliance of mouth all the way thru the hoary hundreds 3 4. Coleridge & Southey brothers-in-law —the Fricker sisters, Edith & Sarah Coleridge & Sarah Fricker married 10-4-95 son Hartley born September 19, 1996 short-lived Berkeley in May 1998 Derwent Coleridge on September 14, 1800 & Sara on Dec 23, ’02 5. -

Sensate Focus (Mark Fell) Y (Sensate Focus 1.666666) [Sensate Focus

Sensate Focus (Mark Fell) Y (Sensate Focus 1.666666) [Sensate Focus / Editions M ego] Tuff Sherm Boiled [Merok] Ital - Ice Drift (Stalker Mix) [Workshop] Old Apparatus Chicago [Sullen Tone] Keith Fullerton Whitman - Automatic Drums with Melody [Shelter Press] Powell - Wharton Tiers On Drums [Liberation Technologies] High Wolf Singularity [Not Not Fun] The Archivist - Answers Could Not Be Attempted [The Archivist] Kwaidan - Gateless Gate [Bathetic Records] Kowton - Shuffle Good [Boomkat] Random Inc. - Jerusalem: Tales Outside The Framework Of Orthodoxy [RItornel] Markos Vamvakaris - Taxim Zeibekiko [Dust-To-Digital] Professor Genius - À Jean Giraud 4 [Thisisnotanexit] Suns Of Arqa (Muslimgauze Re-mixs) - Where's The Missing Chord [Emotional Rescue ] M. Geddes Genras - Oblique Intersection Simple [Leaving Records] Stellar Om Source - Elite Excel (Kassem Mosse Remix) [RVNG Intl.] Deoslate Yearning [Fauxpas Musik] Jozef Van Wissem - Patience in Suffering is a Living Sacrifice [Important Reords ] Morphosis - Music For Vampyr (ii) Shadows [Honest Jons] Frank Bretschneider machine.gun [Raster-Noton] Mark Pritchard Ghosts [Warp Records] Dave Saved - Cybernetic 3000 [Astro:Dynamics] Holden Renata [Border Community] the postman always rings twice the happiest days of your life escape from alcastraz laurent cantet guy debord everyone else olga's house of shame pal gabor billy in the lowlands chilly scenes of winter alambrista david neves lino brocka auto-mates the third voice marcel pagnol vecchiali an unforgettable summer arrebato attila -

Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward

THE INTERNATIONAL FILM MAGAZINE Index to Volume 29 January to December 2019 Compiled by Patricia Coward How to use this Index The first number after a title refers to the issue month, and the second and subsequent numbers are the page references. Eg: 8:9, 32 (August, page 9 and page 32). THIS IS A SUPPLEMENT TO SIGHT & SOUND SUBJECT INDEX Film review titles are also Akbari, Mania 6:18 Anchors Away 12:44, 46 Korean Film Archive, Seoul 3:8 archives of television material Spielberg’s campaign for four- included and are indicated by Akerman, Chantal 11:47, 92(b) Ancient Law, The 1/2:44, 45; 6:32 Stanley Kubrick 12:32 collected by 11:19 week theatrical release 5:5 (r) after the reference; Akhavan, Desiree 3:95; 6:15 Andersen, Thom 4:81 Library and Archives Richard Billingham 4:44 BAFTA 4:11, to Sue (b) after reference indicates Akin, Fatih 4:19 Anderson, Gillian 12:17 Canada, Ottawa 4:80 Jef Cornelis’s Bruce-Smith 3:5 a book review; Akin, Levan 7:29 Anderson, Laurie 4:13 Library of Congress, Washington documentaries 8:12-3 Awful Truth, The (1937) 9:42, 46 Akingbade, Ayo 8:31 Anderson, Lindsay 9:6 1/2:14; 4:80; 6:81 Josephine Deckers’s Madeline’s Axiom 7:11 A Akinnuoye-Agbaje, Adewale 8:42 Anderson, Paul Thomas Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), Madeline 6:8-9, 66(r) Ayeh, Jaygann 8:22 Abbas, Hiam 1/2:47; 12:35 Akinola, Segun 10:44 1/2:24, 38; 4:25; 11:31, 34 New York 1/2:45; 6:81 Flaherty Seminar 2019, Ayer, David 10:31 Abbasi, Ali Akrami, Jamsheed 11:83 Anderson, Wes 1/2:24, 36; 5:7; 11:6 National Library of Scotland Hamilton 10:14-5 Ayoade, Richard -

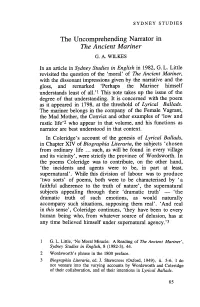

The Uncomprehending Narrator in the Ancient Mariner G

SYDNEY STUDIES The Uncomprehending Narrator in The Ancient Mariner G. A. WILKES In an article in Sydney Studies in English in 1982, G. L. Little revisited the question of the 'moral' of The Ancient Mariner, with the dissonant impressions given by the narrative and the gloss, and remarked 'Perhaps the Mariner himself understands least of all.' 1 This note takes up the issue of the degree of that understanding. It is concerned with the poem as it appeared in 1798, at the threshold of Lyrical Ballads. The mariner belongs in the company of the Female Vagrant, the Mad Mother, the Convict and other examples of 'low and rustic life'2 who appear in that volume, and his functions as narrator are best understood in that context. In Coleridge's account of the genesis of Lyrical Ballads, in Chapter XIV of Biographia Literaria, the subjects 'chosen from ordinary life ... such, as will be found in every village and its vicinity', were strictly the province of Wordsworth. In the poems Coleridge was to contribute, on the other hand, 'the incidents and agents were to be, in part at least, supernatural'. While this division of labour was to produce 'two sorts' of poems, both were to be characterised by 'a faithful adherence to the truth of nature', the supernatural subjects appealing through their 'dramatic truth' - 'the dramatic truth of such emotions, as would naturally accompany such situations, supposing them real'. 'And real in this sense', Coleridge continues, 'they have been to every human being who, from whatever source of delusion, has at any time believed himself under supernatural agency.'3 G. -

The Rime of the Ancient Mariner

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, June 2017, Vol. 7, No. 6, 675-678 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2017.06.006 D DAVID PUBLISHING The Images in The Rime of the Ancient Mariner XING Fang-fang, HUA Yan University of Shanghai for Science and Technology, Shanghai, China The paper mainly talks about the background of S. T. Coleridge and the images of The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. As for the images, the wind, the albatross and the snake will be thoroughly discussed. There are many different images which also have different meanings and connotations in the context. What’s more, the poem expresses the theme of the metabolic relationships between men and nature: harmony, conflict or compromise. Keywords:The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, S. T. Coleridge, images Introduction Samuel Taylor Coleridge is one of the most significant poets and critics in English literature. Generally, his poems are mainly composed of two parts: one is using common language to depict common things and ordinary people; the other is using unique imagination to describe supernatural things. The Rime of the Ancient Mariner belongs to the second group (Coleridge, 2004). It is one of his famous poems, which helps him win lots of fame and makes him firmly stand in literature field. Meanwhile, this poem is also Coleridge’s major contribution to the Lyrical Ballads. Some critics blame Coleridge for his lack of morals in his poems. But actually, this poem contains lots of morals according to Coleridge. Coleridge succeeds in exploring the theme of sin by his rich imagination and the depicting supernatural. -

Scott Sigel Assistant Professor of Spanish Minot State University Minot, North Dakota

Journal of Foreign Languages, Cultures and Civilizations 1(1); June 2013 pp. 45-48 Sigel On the Big Screen in the Great, Great Plains: How We Talk to Each Other in North Dakota Scott Sigel Assistant Professor of Spanish Minot State University Minot, North Dakota I'm just a singer of simple songs I'm not a real political man I watch CNN but I'm not sure I can tell You the difference between Iraq and Iran. -Alan Jackson I am grateful for conversations about our film program over the past two years at film events in Belfast, Belgrade, Abu Dhabi, Ndjamena, and Lagos, and above all to my students at Minot State University and the audience for our MSU International Film Series. When we started the Minot State University International Film Series in January 2005, only one student showed up for a screening and discussion of Lost Boys of Sudan. Our promotion depended on the volunteer contribution of a poster by a student in a graphic design class. We hadn't yet learned how to integrate international films into our foreign language and literature classes, nor the importance of reaching out to the city of Minot on the other side of University Avenue from our campus. From there, we experimented with a French Film Series offered by the Consulate of France in Chicago in 2008. Then in the fall of 2010 we decided to reboot the MSU International Film Series as a monthly campus and community event in the main theater on campus. We became known again for Tuesday evening foreign films, which in the past decades had been popular with students from time to time. -

6. Silent Light: Inability to Choose Between Conflicting Values – Robvanes.Com

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Silent Light: Inability to Choose between Conflicting Values van Es, R. Publication date 2015 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): van Es, R. (Author). (2015). Silent Light: Inability to Choose between Conflicting Values. Web publication/site, RobvanEs.com. http://www.robvanes.com/2015/08/09/6-silent-light-inability- to-choose-between-conflicting-values/ General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:25 Sep 2021 6. Silent Light: Inability to Choose between Conflicting Values – RobvanEs.com RobvanEs.com TRAINING AND ADVICE IN ORGANIZATIONAL PHILOSOPHY Home Consultant Senior Lecturer Publications Biography Blog Contact 6. Silent Light: Inability to Choose between Conflicting Values 9 August 2015 The protagonist in Sophie’s Choice faces an impossible choice under great time Movie blogs pressure.