Coversheet for Thesis in Sussex Research Online

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Ppr) Infection in Sindh Province of Pakistan- a One Year Study

ALI ET AL (2019), FUUAST J.BIOL., 9(1): 149-157 PREVALENCE OF PESTE DES PETITS RUMINANTS (PPR) INFECTION IN SINDH PROVINCE OF PAKISTAN- A ONE YEAR STUDY SYED NOMAN ALI1,2, SHAHID ALI KHAN3, MASOOD VANDIAR4, RIASAT WASEE ULLAH5AND SHAHANA UROJ KAZMI6 1Livestock Department, Government of the Sindh 2Department of Agriculture & Agribusiness Management, University of Karachi, Pakistan. 3Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Islamabad Pakistan. ([email protected]). 4Central Veterinary Diagnostics Laboratory, Tando Jam. ([email protected]) 5Veterinary Research Institute, Lahore ([email protected]) 6Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Dadabhoy University (DIHE) & the University of Karachi, Pakistan ([email protected]) Corresponding author email: [email protected] الخہص وموجدہۺررسیچۺاپاتسکنۺےکۺوصہبۺدنسھۺںیمۺرکبویںۺاورۺڑیھبوںۺںیمۺاپےئۺوایلۺامیبریۺاکاٹ (PPR) یکۺوموجدیگ،ۺاابسبۺاورۺرٹنکولۺرکےنۺےکۺاکرۺآدمۺرطےقیۺولعممۺرکےنۺےکۺ ےئلۺیکۺیئگۺےہ۔ۺسجۺےکۺدورانۺایسۺامیبریۺیکۺ۷۴۸ۺۺوابء (Outbreaks)اکۺاجزئہۺایلۺایگۺوجۺوصہبۺدنسھۺےکۺ۹۲ۺںیمۺےسۺ۶۲االضعۺںیمۺاپیئۺیئگۺبسۺےسۺزایدہۺوابءۺ۱۵.۷۲ۺدصیفۺایٹمریۺعلضۺ ںیمۺاورۺبسۺےسۺمکۺرعےصۺیکۺوابءۺرمعۺوکٹۺعلضۺںیمۺراکیرڈۺیکۺیئگۺوجۺہکۺ ۵ۺدنۺیھتۺاسۺےکۺالعوہۺےبملۺرعہصۺیکۺامیبریۺﻻڑاکہنۺںیمۺاپیئۺیئگۺوجہک ۶۲ۺدنۺیھت۔ۺۺامیبریۺیکۺاشنوینںۺںیمۺمسجۺےکۺ درہجۺرحاتۺںیمۺااضہفF ۶ .۷۰۱ےسF ۲ .۲۰۱راکیرڈۺایکۺایگ۔ۺآوھکنںۺیکۺوسزش،ۺآوھکنںۺاورۺانکۺےسۺاگڑیۺرموطتب،ۺاھکیسنۺاورۺدتسۺاپےئۺےئگ،ۺہنمۺںیمۺوسمڑوںۺرپۺﻻلۺوسنجۺ ےکۺاشننۺےکۺاسھتۺزابنۺاورۺاگولںۺرپۺیھبۺوسنجۺاورۺزمخۺےکۺاشننۺاپےئۺےئگ۔ ELISAےکۺےجیتنۺرپ ANOVA -

PAKISTAN: FLOODS/RAINS 2012 Series No. 4 RAPID

Pakistan Floods / Rains 2012: Rapid Crop Damage Assessment: Series No. 4 PAKISTAN: FLOODS/RAINS 2012 Series No. 4 RAPID CROP DAMAGE ASSESSMENT October 30, 2012 Pakistan Space & Food and Agriculture Upper Atmosphere Organization of the Research Commission United Nations Pakistan Floods / Rains 2012: Rapid Crop Damage Assessment: Series No. 4 ISBN : 978-969-9102-11-0 Pakistan Space & Upper Atmosphere Research Commission SPARC, Islamabad Phone: 051-9273312, 051-4611792 e-mail:[email protected], Website: www.suparco.gov.pk Pakistan Floods / Rains 2012: Rapid Crop Damage Assessment: Series No. 4 Foreword Pakistan faced floods and tormenting rains during the last three consecutive monsoons from 2010 to 2012. During these floods, the ground communication systems were generally disrupted and information on flood extent and damage through ground reporting services was not available for taking timely decisions. To address the situation and to ensure continuous provision of current and timely information to the concerned stakeholder’s and decision makers satellite remote sensing and GIS technologies were extensively utilized. SUPARCO in collaboration with FAO started generating data on daily basis on flood extent, damage to households, infrastructure and crops besides undertaking detailed Damage Need Assessment (DNA). This fast track supply of information made it possible to reach out to affected and displaced masses for supply of food, medical care, relief, rehabilitation and follow up programs. In the aftermath of floods, monitoring of flood recession and ponding of water in the affected areas on decadal basis was also carried out for several months. All of this work was published by SUPARCO-FAO jointly in three reports (Reports 1 to 3). -

Sindh Flood 2011 - Union Council Ranking - Sanghar District

PAKISTAN - Sindh Flood 2011 - Union Council Ranking - Sanghar District Union council ranking exercise, coordinated by UNOCHA and UNDP, is a joint effort of Government and humanitarian partners Community Restoration Food Education in the notified districts of 2011 floods in Sindh. Its purpose is to: Identify high priority union councils with outstanding needs. SHAHEED SHAHEED SHAHEED BENAZIRABAD KHAIRPUR BENAZIRABAD KHAIRPUR BENAZIRABAD KHAIRPUR Facilitate stackholders to plan/support interventions and divert Shah Shah Shah Sikandarabad Sikandarabad Sikandarabad Paritamabad Paritamabad Paritamabad Gujri Gujri resources where they are most needed. Gul Gul Gujri Khadro Khadwari Khadro Khadwari Gul Khadro Khadwari Muhammad Muhammad Muhammad Laghari Laghari Laghari Shahpur Sanghar Shahpur Sanghar Shahpur Sanghar Serhari Chakar Kanhar Serhari Chakar Kanhar Provide common prioritization framework to clusters, agencies Shah Shah Serhari Chakar Kanhar Barhoon Barhoon Barhoon Shah Mardan Abad Mardan Abad Shahdadpur Mian Chutiaryoon Shahdadpur Mian Chutiaryoon Shahdadpur Mardan Abad Mian Chutiaryoon Asgharabad Jafar Sanghar 2 Asgharabad Jafar Sanghar 2 Asgharabad Jafar Sanghar 2 Khan Khan Lundo Soomar Sanghar 1 Lundo Soomar Sanghar 1 Lundo Soomar Khan Sanghar 1 and donors. Faqir HingoroLaghari Laghari Laghari Faqir Hingoro Faqir Hingoro Kurkali Kurkali Kurkali Jatia Jatia Jatia Maldasi Sinjhoro Bilawal Hingoro Maldasi Sinjhoro Bilawal Hingoro Maldasi Sinjhoro Bilawal Hingoro Manik Manik Manik Tahim Khipro Tahim Khipro First round of this exercise is completed from February - March Khori Khori Tahim Khipro Kumb Jan Nawaz Kumb Jan Nawaz Kumb Khori Pero Jan Nawaz DarhoonTando Ali DarhoonTando Pero Ali DarhoonTando Pero Ali Faqir Jan Nawaz Ali Faqir Jan Nawaz Ali Faqir Jan Nawaz Ali AdamShoro Hathungo AdamShoro Hathungo AdamShoro Hathungo Nauabad Nauabad Nauabad 2012. -

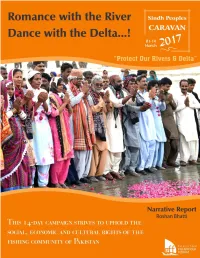

Caravan Report

1 | P a g e 2 | P a g e Background: If there is ever to be a Third World War, many believe it will be fought over water, with South Asia serving as the flashpoint. The region houses a quarter of the world’s population and has less than 5 percent of the global annual renewable water resources. Low water availability per person and high frequency of extreme weather events, including severe droughts, further increase the vulnerability of the area. Any disturbance by the country upstream is likely to impact life downstream. Also, as heightened interests to tame and exploit a river through dams, canals and hydel projects suggest, this region will be a zone of constant confrontations in the future. The vision 2025 of Pakistan clearly indicates that the existing flow of water of rivers will be diverted through building various mega schemes for water conservation for energy and agricultural purposes. Such decisions and policies based on vested political interests will further aggravate the socio-economic conditions of deltaic communities of the Sindh. A large water share of the River Indus is utilized by Punjab Province. Resultantly, the lower end of the River Indus that used to be known as “Mighty River Indus” has been reduced to the level of canal shows only tiny inconsistent storage of water. Such a massive destruction of the River Indus has led to the death of livelihood of the deltaic people. The Pakistan government has been planning to build more dams on Indus River. The PFF believes that the indigenous people along with the other natural habitat have the basic right to use the land and water first. -

Improving Decision-Making Systems for Decentralized Primary Education Delivery in Pakistan

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available from www.rand.org as a public CHILD POLICY service of the RAND Corporation. CIVIL JUSTICE EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS NATIONAL SECURITY The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit research POPULATION AND AGING organization providing objective analysis and effective PUBLIC SAFETY solutions that address the challenges facing the public SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY and private sectors around the world. SUBSTANCE ABUSE TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE Support RAND WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore Pardee RAND Graduate School View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND PDFs to a non-RAND Web site is prohibited. RAND PDFs are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the Pardee RAND Graduate School (PRGS) dissertation series. PRGS dissertations are produced by graduate fellows of the Pardee RAND Graduate School, the world’s leading producer of Ph.D.’s in policy analysis. The dissertation has been supervised, reviewed, and approved by the graduate fellow’s faculty committee. Improving Decision-making Systems for Decentralized Primary Education Delivery in Pakistan Mohammed Rehan Malik This document was submitted as a dissertation in July 2007 in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the doctoral degree in public policy analysis at the Pardee RAND Graduate School. -

Download File

Integrated KAP Survey Knowledge, Attitudes, and Practices Jamshoro District, Sindh Province, Pakistan December 2016 Table of Contents Acknowledgments ....................................................................................................................................................... 3 Acronyms and Abbreviations ....................................................................................................................................... 4 1. Executive Summary .......................................................................................................................................... 5 2. Introduction......................................................................................................................................................... 7 3. Survey Objectives ............................................................................................................................................. 9 4. Methodology....................................................................................................................................................... 9 4.1 Type of Survey and Survey Area ................................................................................................................. 9 4.2 Study Period .................................................................................................................................................. 10 4.3 Study Population ......................................................................................................................................... -

Covid-19 Emergency Response

COVID-19 EMERGENCY RESPONSE Daily Situation Report- April 16, 2020 Sindh Rural Support Organizaiton (SRSO) SRSO Complex, Shikarpur Road, Sukkur (Sindh), Pakistan, Ph.#: 071-56271820 Website: www.srso.org.pk Daily Situation Report All the cities of Sindh are locked down. Daily wagers faced much difficulties to meet their ends. In such a pandemic and lockdown situation poor people of the community cannot afford their basic needs of life. In this situation, the Community didn’t leave alone to the poor daily wagers and elderly people of their communities. SRSO through representatives of community institutions (CIs) and staff are responding COVID-19 emergency within its outreach areas through Community Savings, Ration and Vegetables Distribution, Linkages Development, Identification of deserving HHs, delivering awareness sessions on precautionary measures to fight COVID-19 and Registration of needy and poor families under the Govt. of Pakistan Ehsaas Emergency Cash Programme. Households and individuals are being supported with Cash, Ration and capitalizing LSO linkages for relief activities in their concerned areas. SRSO well trained human capital is engaged in Government relief activities through identification of deserving beneficiaries, distribution of ration bags, conducting awareness sessions on preventive measures to combat COVID-19 SRSO is also facilitating the Government of Sindh in the identification of deserving families and distribution of food items in most needy households. SRSO outreach and scale of response to COVID-19 outbreak -

Population Distribution in Sindh According to Census 2017 (Population of Karachi: Reality Vs Expectation)

Volume 3, Issue 2, February – 2018 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology ISSN No:-2456 –2165 Population Distribution in Sindh According to Census 2017 (Population of Karachi: Reality vs Expectation) Dr. Faiza Mazhar TTS Assistant Professor Geography Department. Government College University Faisalabad, Pakistan Abstract—Sindh is our second largest populated province. Historical Populations Growth of Sindh It has a great role in culture and economy of Pakistan. Karachi the largest city of Pakistan in terms of population Census Year Total Population Urban Population also has a unique impact in development of Pakistan. Now 1951 6,047,748 29.23% according to the current census of 2017 Sindh is again 1961 8,367,065 37.85% standing on second position. Karachi is still on top of the list in Pakistan’s ten most populated cities. Population of 1972 14,155,909 40.44% Karachi has not grown on an expected rate. But it was due 1981 19,028,666 43.31% to many reasons like bad law and order situation, miss management of the Karachi and use of contraceptive 1998 29,991,161 48.75% measures. It would be wrong if it is said that the whole 2017 47,886,051 52.02% census were not conducted in a transparent manner. Source: [2] WWW.EN.WIKIPEDIA.ORG. Keywords—Component; Formatting; Style; Styling; Insert Table 1: Temporal Population Growth of Sindh (Key Words) I. INTRODUCTION According to the latest census of 2017 the total number of population in Sindh is 48.9 million. It is the second most populated province of Pakistan. -

Shikarpur Profile

District Shikarpur Profile “CHILDREN, ESPECIALLY GIRLS AGED 2-12 HAVE ACCESS TO QUALITY EDUCATION WITH IMPROVED INFRASTRUCTURE AND SAFE LEARNING ENVIRONMENT” Whole Schools Improvement Program (WSIP) Funded by: Dubai Cares Implemented by: Idara-e-Taleem-o-Aagahi (ITA) District Shikarpur Profile 1 | P a g e Sr. List of Contents Page # # 1. Situation Analysis of City District Shikarpur 4 2. History 4 3. Geography 4 4. Administration 4 5. Population 4 6. Political Parties & Elections 2013 4 7. Shikarpur District Education Profile 5 8. Learning Levels 7 District Shikarpur Profile 2 | P a g e Table List of the Table Page No. # 1. National Assembly Elections 2013 4 2. Punjab Provincial Assembly Elections 2013 5 3. POPULATION of School Aged Children By YEAR AGE, SEX AND RURAL 5 4. District Education Index (Sindh) 5 5. Population That Has Ever Attended School 6 6. Literacy-Population 10 Years and Older 6 7. Gross Enrolment Rate at the Primary Level 6 8. Net Enrolment Rate at the Primary Level 6 9. Number of Government Schools 7 10. Enrollment in Government Schools 7 11. Government Teachers 8 District Shikarpur Profile 3 | P a g e District Shikarpur Profile Situation Analysis of City District Shikarpur History1 Shikarpur is known as “old Paris” because of its perfume industry, or according to some the name was given due to modern buildings of that time. It is also famous for its pickles and sweets, as well as it has a large market for cotton and pottery. Shikarpur has always been the part of trade route for Central Asian countries through Bolan Pass, and local merchants had dealings with many towns in Central Asia. -

Pdf | 951.36 Kb

P a g e | 1 Operation Updates Report Pakistan: Monsoon Floods DREF n° MDRPK019 GLIDE n° FL-2020-000185-PAK Operation update n° 1; Date of issue: 6/10/2020 Timeframe covered by this update: 10/08/2020 – 07/09/2020 Operation start date: 10/08/2020 Operation timeframe: 6 months; End date: 28/02/2021 Funding requirements (CHF): DREF second allocation amount CHF 339,183 (Initial DREF CHF 259,466 - Total DREF budget CHF 598,649) N° of people being assisted: 96,250 (revised from the initially planned 68,250 people) Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners currently actively involved in the operation: IFRC Pakistan Country Office is actively involved in the coordination and is supporting Pakistan Red Crescent Society (PRCS) in this operation. In addition, PRCS is maintaining close liaison with other in-country Movement partners: International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), German Red Cross (GRC), Norwegian Red Cross (NorCross) and Turkish Red Crescent Society (TRCS) – who are likely to support the National Society’s response. Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA), Provincial Disaster Management Authorities (PDMAs), District Administration, United Nations (UN) and local NGOs. Summary of major revisions made to emergency plan of action: Another round of continuous heavy rains started in most part of the country on the week of 20 August 2020 until 3 September 2020 intermittently. The second round of torrential rains caused urban flooding in the Sindh province and flash flooding in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP). New areas have been affected by the urban flooding including the districts of Malir, Karachi Central, Karachi West, Karachi East and Korangi (Sindh), and District Shangla, Swat and Charsadda in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. -

CWS-P/A Has Empowered Women in Thatta District with Skills, Basic Education, and Knowledge on Staying Safe

CWS-P/A has empowered women in Thatta District with skills, basic education, and knowledge on staying safe. Photo by Shahzad A. Fayyaz. FOR PRIVATE CIRCULATION ONLY January - April 2014 Newsletter Volume 13, Issue 33 2014 Dear Readers, We welcome you to read CWS-P/A’s first newsletter for 2014. This January to April edition contains news about projects which continually impact the lives of communities in Pakistan and Afghanistan in positive ways. The projects include interventions in health and livelihoods for families in the districts of Kohat, Mansehra, Haripur, and Thatta in Pakistan. In Afghanistan, CWS-P/A continues to strengthen educational opportunities, especially for girls, by increasing awareness among parents and community members and by building the capacity of teachers. The newsletter also highlights work in Afghanistan toward improving health, especially for women and children. Additionally, read about the organization’s work for minorities and in raising awareness on the issues they face. There is further news about CWS-P/A’s work in promoting quality and accountability. This edition’s Hot Topic is about contingency planning for humanitarian organizations. We express our gratitude to you for taking the time to read our newsletter. You may send feedback and In This Edition suggestions to [email protected] The CWS - P/A team Quality and Accountability In this Edition 02 for Project Cycle Management Suggested Reading 02 – A Pocket Booklet for Field Mission Statement 02 Practitioners News from CWS-P/A 03 Vocational Training Inspires Young Afghan Men and Women 10 Implementing Education with Sports and Play 12 Guldasta’s Story: Helping Women Regain Good Health 14 Words of Wisdom 16 Hot Topic 16 Suggested Reading By: Sylvie Robert and Astrid de Valon Table of Contents Table The first edition of the Quality and Accountability for Project Cycle Management booklet is a CWS–P/A as an ecumenical organization user-friendly guide to the various quality will struggle for a community based and accountability tools and standards. -

Socio Economic Baseline Survey

RSPN Baseline Survey Report Socio-economic Baseline Survey of Shikarpur District Sindh Rural Support Organisation This document has been prepared with the financial support of the Department for International Development (DFID) of the Government of United Kingdom and in collaboration with the Sindh Rural Support Organization (SRSO). Consultants:APEX Consulting Pakistan Client:Rural Support Programmes Network (RSPN) Project:Union Council Based Poverty Reduction Programme (UCBPRP) Assignment:Socio-economic Baseline Survey of Kashmore District Report:Final Baseline Report Team Members: Syed Sardar Ali, Ahmed Afzal, Abdul Hameed, Yasir Majeed and Tahir Jelani Art Directed & Designed by: Faisal Ali (Ali Graphics) Copyrights(c) 2010 Rural Support Programmes Network Monitoring Evaluation and Research Section Rural Support Programmes Network (RSPN) House NO. 7, Street 49, F-6/4, Islamabad, Pakistan Tel: (92-51) 2822476, 2821 736 The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this paper are entirely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of RSPN, SRSO or DFID. Acknowledgements The consultants wish to express their gratitude to Ms. Shandana Khan, Chief Executive Officer RSPN, for providing opportunity to conduct this socio- economic baseline survey. We further thank Mr. Khaleel Ahmed Tetlay, Chief Operating Officer RSPN, for his guidance during assignment planning. A special thanks is due to Mr. Fazal Ali Saadi, MER Specialist RSPN, for cooperating and facilitating us throughout the assignment. We further thank Mr. Ghulam Rasool Samejo, Mr. Ali Bux and Mr. Abdul Sammad of SRSO for their technical and administrative cooperation in the successful completion of this assignment. CONTENTS 1 1. Executive Summary 1-4 2 2.