Download File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Caravan Report

1 | P a g e 2 | P a g e Background: If there is ever to be a Third World War, many believe it will be fought over water, with South Asia serving as the flashpoint. The region houses a quarter of the world’s population and has less than 5 percent of the global annual renewable water resources. Low water availability per person and high frequency of extreme weather events, including severe droughts, further increase the vulnerability of the area. Any disturbance by the country upstream is likely to impact life downstream. Also, as heightened interests to tame and exploit a river through dams, canals and hydel projects suggest, this region will be a zone of constant confrontations in the future. The vision 2025 of Pakistan clearly indicates that the existing flow of water of rivers will be diverted through building various mega schemes for water conservation for energy and agricultural purposes. Such decisions and policies based on vested political interests will further aggravate the socio-economic conditions of deltaic communities of the Sindh. A large water share of the River Indus is utilized by Punjab Province. Resultantly, the lower end of the River Indus that used to be known as “Mighty River Indus” has been reduced to the level of canal shows only tiny inconsistent storage of water. Such a massive destruction of the River Indus has led to the death of livelihood of the deltaic people. The Pakistan government has been planning to build more dams on Indus River. The PFF believes that the indigenous people along with the other natural habitat have the basic right to use the land and water first. -

Population Distribution in Sindh According to Census 2017 (Population of Karachi: Reality Vs Expectation)

Volume 3, Issue 2, February – 2018 International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology ISSN No:-2456 –2165 Population Distribution in Sindh According to Census 2017 (Population of Karachi: Reality vs Expectation) Dr. Faiza Mazhar TTS Assistant Professor Geography Department. Government College University Faisalabad, Pakistan Abstract—Sindh is our second largest populated province. Historical Populations Growth of Sindh It has a great role in culture and economy of Pakistan. Karachi the largest city of Pakistan in terms of population Census Year Total Population Urban Population also has a unique impact in development of Pakistan. Now 1951 6,047,748 29.23% according to the current census of 2017 Sindh is again 1961 8,367,065 37.85% standing on second position. Karachi is still on top of the list in Pakistan’s ten most populated cities. Population of 1972 14,155,909 40.44% Karachi has not grown on an expected rate. But it was due 1981 19,028,666 43.31% to many reasons like bad law and order situation, miss management of the Karachi and use of contraceptive 1998 29,991,161 48.75% measures. It would be wrong if it is said that the whole 2017 47,886,051 52.02% census were not conducted in a transparent manner. Source: [2] WWW.EN.WIKIPEDIA.ORG. Keywords—Component; Formatting; Style; Styling; Insert Table 1: Temporal Population Growth of Sindh (Key Words) I. INTRODUCTION According to the latest census of 2017 the total number of population in Sindh is 48.9 million. It is the second most populated province of Pakistan. -

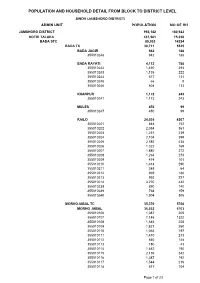

Jamshoro Blockwise

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL SINDH (JAMSHORO DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH JAMSHORO DISTRICT 993,142 180,922 KOTRI TALUKA 437,561 75,038 BADA STC 85,033 14234 BADA TC 30,711 5525 BADA JAGIR 942 188 355010248 942 188 BADA RAYATI 4,112 788 355010242 1,430 294 355010243 1,135 222 355010244 677 131 355010245 66 8 355010246 804 133 KHANPUR 1,173 243 355010241 1,173 243 MULES 450 99 355010247 450 99 RAILO 24,034 4207 355010201 844 152 355010202 2,054 361 355010203 1,251 239 355010204 2,104 399 355010205 2,585 438 355010206 1,022 169 355010207 1,880 272 355010208 1,264 273 355010209 474 101 355010210 1,414 290 355010211 348 64 355010212 969 186 355010213 993 227 355010214 3,270 432 355010238 890 140 355010239 768 159 355010240 1,904 305 MORHOJABAL TC 35,370 5768 MORHO JABAL 35,032 5703 355010106 1,087 205 355010107 7,146 1322 355010108 1,646 228 355010109 1,821 260 355010110 1,065 197 355010111 1,410 213 355010112 840 148 355010113 180 43 355010114 1,462 190 355010115 2,136 342 355010116 1,387 192 355010117 1,544 216 355010118 617 104 Page 1 of 23 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL SINDH (JAMSHORO DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH 355010119 79 15 355010120 3,665 538 355010121 951 129 355010122 2,161 343 355010123 2,169 355 355010124 1,468 261 355010125 2,198 402 TARBAND 338 65 355010126 338 65 PETARO TC 18,952 2941 ANDHEJI-KASI 1,541 292 355010306 1,541 292 BELO GHUGH 665 134 355010311 665 134 MANJHO JAGIR 659 123 355010307 659 123 MANJHO RAYATI 1,619 306 355010310 1,619 -

Downloads/Impactofcbtsindhjune2016.Pdf, Page 1 8According to UNICEF, the Total Adult Literacy Rate, 2008-2012 Is 54.9%

PCMA PRE-CRISIS MARKET ANALYSIS 0 Table of Contents Executive Summary and Key Recommendations .................................................................... 2 A. Overview of the PCMA in Sindh ...................................................................................... 5 a. Objectives...................................................................................................................................... 5 B. Methodology .................................................................................................................. 5 C. Focus populations and locations ..................................................................................... 7 D. Crisis scenarios and selected timeframe ........................................................................ 10 E. Market systems and season of the analysis ................................................................... 14 a. Seasonal calendar ....................................................................................................................... 14 F. Narrative of key actors and key findings ........................................................................ 15 G. Market maps for goats, water, and fodder .................................................................... 21 H. Summary of key findings ............................................................................................... 28 I. Gap Analysis: Comparing gap in needs with market capacity ......................................... 29 a. Key analytical questions -

47094-001: Jamshoro Power Generation Project

Land Acquisition and Resettlement Plan Draft Project Number: 47094-001 October 2013 PAK: Jamshoro Power Generation Project Prepared by Engconsult Ltd. for the Asian Development Bank CONTENTS Page ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................................................................. 3 DEFINITION OF TERMS ....................................................................................................... 4 I. PROJECT DESCRIPTION ......................................................................................... 7 II. SCOPE OF LAND ACQUISITION AND RESETTLEMENT ........................................ 8 III. INFORMATION DISCLOSURE, CONSULTATION, AND PARTICIPATION ............ 10 IV. LEGAL FRAMEWORK ............................................................................................. 11 A. Land Acquisition Act, 1894 (LAA) .............................................................................. 11 B. Sindh Land Acquisition (Companies) Rules, 1963 ..................................................... 12 C. ADB’s Policy Principles for Involuntary Resettlement ................................................ 12 D. Comparison of Key Features of LAA 1894 and ADB Policy Principles and Practices 14 V. ENTITLEMENTS, ASSISTANCE AND BENEFITS .................................................. 16 A. Entitlements .............................................................................................................. 16 B. Eligibility .................................................................................................................. -

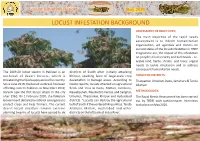

2020-05-12 --Locust Report.Cdr

Locust Situation Report May 2020 LOCUST INFESTATION BACKGROUND ASSESSMENT OF OBJECTIVES: The main objecve of the rapid needs assessment is to inform humanitarian organizaon, aid agencies and donors on current status of the locust infestaon in TRDP Programme are; the impact of the infestaon on people's food security and livelihoods - i.e. arable land, herbs, shrubs and trees; urgent needs to tackle infestaon and to address consequent humanitarian needs. The 2019-20 locust swarm in Pakistan is an districts of Sindh aer inially aacking outbreak of desert locusts, which is Khirpur, sparking fears of large-scale crop TARGETED DISTRICTS: threatening the food supply across the country. devastaon in barrage areas. According to Tharparkar, Umerkot, Dadu, Jamshoro & Tando Since June 2019, the locust outbreak has been media reports, locusts aacked on agricultural Allahyar affecng eastern Pakistan. In November 2019, fields and tress in Dadu, Maari, Jamshoro, Karachi saw the first locust aack in the city Nawabashah, Naushehro Feroze and Sanghar, METHODOLOGY: aer 1961. On 1 February 2020, the Pakistani Umerkot, Tharparkar, Khirpur and Hyderabad The Rapid Needs Assessment has been carried Government declared a naonal emergency to districts. "Locusts can destroy the agricultural out by TRDP, with quesonnaire. Interviews protect crops and help farmers. The current belt of Sindh if they entered Mirpurkhas, Tando took place on May 2020. desert locust situaon remains extreme Allahyar, Maari, Hyderabad and other alarming Swarms of locusts have spread to six districts on the le bank of Indus River. Locust Situaon Report May 2020 DISTRICT WISE LOCUST SITUATION LOCUST SITUATION: THARPARKAR Mosepota, Roheera, Kuo, Verhari Drs, Mithrio The Desert Locust, found in various parts of Tharparkar, considered the most destrucve Union Councils migratory pest because they are highly mobile and can form swarms containing millions of 70 64 locusts, leading to devastang impacts on 60 crops, trees, pasture and fodder. -

Determination of Arsenic and Health Risk Assessment in the Ground

Determination of Arsenic and Health Risk Assessment in the Ground Water of Sindh, Pakistan Zulfiqar Bhatti, Khadija Qureshi, Inamullah Bhatti, Imran Nazir Unar, Mohammad Yar Khuhawar To cite this version: Zulfiqar Bhatti, Khadija Qureshi, Inamullah Bhatti, Imran Nazir Unar, Mohammad Yar Khuhawar. Determination of Arsenic and Health Risk Assessment in the Ground Water of Sindh, Pakistan. Mehran University Research Journal of Engineering and Technology, Mehran University of Engineering and Technology, Jamshoro, Pakistan, 2017, 36 (4), pp.1037-1048. hal-01705647 HAL Id: hal-01705647 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01705647 Submitted on 9 Feb 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution| 4.0 International License Determination of Arsenic and Health Risk Assessment in the Ground Water of Sindh, Pakistan ZULFIQAR ALI BHATTI*, KHADIJA QURESHI*, INAMULLAH BHATTI*, IMRAN NAZIR UNAR*, AND MOHAMMAD YAR KHUHAWAR** RECEIVED ON 14.02.2017 ACCEPTED ON 29.05.2017 ABSTRACT As (Arsenic) is one of the lethal element present at the various locations of the world, putting human beings in danger by polluting the water. Arsenic Kit and atomic absorption spectrometer were used to determine As in ground water of Sindh province, Pakistan. -

4Th DEC 2021

27th NOV - 4th DEC 2021 DRIVE A RICKSHAW ACROSS 300 MILES OF RURAL PAKISTAN AND THEN HAND IT OVER TO A NEEDY FAMILY FOR THEIR INCOME GENERATION CONTENTS Introduction 3 The Cause 5 Day One 6 Day Two 7 Day Three 10 Day Four 12 INTRODUCTION Day Five 15 Day Six 17 Brace yourselves! Day Seven 19 Explore the sights and sounds of the centuries-old rich culture of Sindh and civilisation of the Indus Valley. Their history Day Eight 20 has given them strong traditions, customs, folklore, a distinct lifestyle and their own language called Sindhi. Frequently Asked Questions 22 Sindh has always been considered the land of art, romance, love, peace and great cultural values. The people of Sindh are colourful and that is depicted by their wholehearted celebrations of Islamic and regional festivals. 02 REGISTER | www.muslimcharity.org.uk/rickshaw2021 03 or call us on 03000 111 786 KEY FACTS Registration Fee: £400 - This includes all costs within Pakistan (hotels, food, accommodation and airport transfers). Fundraising Target: £1,200 individually (or £3,600 as a group of three). This will be used to fund the purchase of a rickshaw and support our Children of the World campaign. What’s not included in the registration fee: International UK- Pakistan return flights, visa fees, PCR test if required. THE CAUSE Sindh has a reputation for textiles, pottery, leatherwork and carpets. The craftsmanship of the people of Sindh began during the period of the Mohenjo-Daro civilization. Funds raised will go towards providing a means of income generation to a needy family through Riding an auto rickshaw is an awesome way to travel that is not only fun but it gives a unique the provision of a rickshaw as well as supporting our education projects as part of our Children way to get a taste of local life. -

KARACHI RANGE 01 Sadar S/N Police Station Name Complete

KARACHI RANGE 01 Sadar S/N Police Station Name Complete Address of PS 01 Preedy Preedy Stret Temple road Karachi 02 City Court City Court near Karachi post office Tahir Saifuddin Road Karachi 03 Artillery Maidan Near Art Councial Pakistan near M.R.Kyani Road Karachi 04 Garden Heera Nund Khaim Sing Road Garden 05 Nabi Bux Heera Nand Cam Singh Road Karachi 06 Eidgah Inside Risala PS Nishtar road Karachi 07 Kharader Kharadar Police Station M.A.Jinnah Road Karachi 08 Mithadar M.A.Jinnah road Karachi 09 Risala Nishtar Road near Juna Market Karachi 10 City Court 02 Clifton S/N Police Station Name Complete Address of PS 11 Darakshan Plot No.1270 Street No.31 Khayaban Roomi Phase No.8 12 Gizri Plot No.P-38,11 Commercial Street Phase No.4 DHA Karachi Plot No.PS-1 Khyaban-e-Razwan Phase No.7 Ext DHA Main 13 Defence Korangi Road Karachi 14 Clifton Near Pak Tawar PTC Telephone Exchange Karachi Plot No.PS-1 Khyaban-e-Razwan Phase No.7 Ext DHA Main 15 Boat Basin Korangi Road Karachi 16 Frere Khaliq uz Zaman Road near Lully Bridge Karachi 03 Gulshan S/N Police Station Name Complete Address of PS 17 Gulshan-e-Igbal 18 Madina Main University Road Saforah Goth Chowrangi Kacchi Abadi 19 Sacahal Karachi 20 New 21 PIB Colony 22 Aziz Bhatti 23 Gulista-e-Jauhar 24 Bahadurabad 04 Kemari S/N Police Station Name Complete Address of PS 25 Jackson 26 KPT 27 Docks 28 Maripur 29 Sher Shah 30 DSP KESC 31 Women PS Gora Qabrastan Main Shahra-e-Faisal Karachi 32 N.A.B PS 33 SHO KESC 05 Liaquat Abad S/N Police Station Name Complete Address of PS 34 Liaquatabad Block 5 -

Innocence Childhood with Miserable Atmosphere

Innocence Childhood With Miserable Atmosphere A Rapid Assessment- 2007 ___________________________________________________________________________________ ___ THARDEEP RURAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMME 1 SINDH-PAKISTAN Innocence Childhood With Miserable Atmosphere A Thardeep Publication Report Compiled by Ashok Suthar Head Office Near Dargah Hussain Shah, Siran Mithi (69230), District Tharparkar Sindh Pakistan. Tel: 0092-232-261-462 Fax: 0092-232-261-379 Child Rights Protection Project Office Near Circuit House, Behind Grid Station Kanji Colony, Mithi (69230), District Tharparkar Sindh, Pakistan Tel: 0092-232-261-577 Coordination Office F-178/3, Block-5, Kehkshan Clifton Karachi Tel: 0092-21-586-8791 Fax: 0092-21-586-8793 Website: www.thardeep.org E-mail: [email protected] All rights reserved 2 “Children must be protected from work which is harmful to their health and development, nor must such work interfere with their education”. Article 32 Conventions on the Rights of the Child. Contents 3 Abbreviations and Acronyms Acknowledgement Preface Overview Objectives Methodology Findings Age wise population and gender ratio: Household economy, livestock belongings and indebt ness Expenditures Livestock belongings Indebt ness Reasons of taking loans Period of loans Sources of loans Working status of children Other details of working children Monthly income of working children Gender wise ages, experiences and working hours of working children Marriage Ages Schooling Health problems Conclusion/Recommendations Working children views Parents’ views -

RDF-Annul-Report-2014.Pdf

Contents: 1 Sustainable Livelihoods & Food Security 1.1 Promotion of Ecological Agriculture in Rural Areas 1.2 Improving Livestock Management 1.3 Skilling Youth of Rural Areas of Sindh 2 Climate Change Adaptation & Disaster Risk Reduction 2.1 Building Adaptive capacities of youth and community members 2.2 Sustainable WASH Assistance in rural areas of District Naushahro Feroz 3 Promoting Quality Primary Education Professional Development Course for the Head Teachers 4 Private Sector Engagement 4.1 Engagement with Oil Exploration and Production Companies 5 Networking and Advocacy Every Drop Counts; Lecture Series on Water Governance What We Work Key Features of Our Work Proactive Community Participation Capacity Building & Mentoring Continuous monitoring & hands on support Transparency & Delegation Dignity Respect to environment & Cultural norms Transforming learning Protection to the rights of vulnerable people Factual Reporting Resource Efficiency RDF Annual Report 2015 RDF in 2014 The development work of RDF in Sindh goes back to the year 2010, when it fielded development activities to improve livelihoods, food security and resilience of the vulnerable communities to withstand disasters. During the year 2014, RDF continued working on program themes with more focus on strengthening and diversifying livelihoods in rural areas of Sindh. Sustainable agriculture techniques were demonstrated and promoted in various villages of district Dadu, Jamshoro, Mirpurkhas, Sanghar and Tharparkar. TVET has been integrated into livelihood programs to make youth employable and contribute in the economy of their households. Around 3,000 young men and women were provided with market driven technical education and vocational trainings. Water Conservation with focus on promotion of micro drip irrigation and spate irrigation is being piloted and promoted in Jamshoro district. -

Petaro–Sehwan Additional Carriageway, Section I

Updated Land Acquisition and Resettlement Plan November 2018 PAK: Central Asia Regional Economic Cooperation Corridor Development Investment Program-Tranche 1 Petaro–Sehwan Additional Carriageway, Section I Prepared by the Environment, Afforestation, Land and Social Wing of the National Highway Authority of Pakistan for the Asian Development Bank. This is an updated version of the draft originally posted in July 2017 available on http://www.adb.org/projects/48404-003/documents. This updated land acquisition and resettlement plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section of this website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Petaro-Sehwan Additional Carriageway Section-1 LARP CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (As of 15 Nov 2018) Currency Unit = Pakistan Rupee/s (PRs) PRs 1.00 = USD $0.007 USD $1.00 = PRs 134.18 ACRONYM AD assistant director ADB Asian Development Bank CBO community-based organization COI corridor of impact DCR district census report DD deputy director DH displaced household DO(R) district officer (revenue) DPs displaced persons EDO executive district officer EIA environmental impact assessment EMP environmental management plan ft. feet GM general manager GOP Government of Pakistan IP indigenous people km kilometres LAA Land Acquisition Act 1894 LAR land acquisition and resettlement LARP land acquisition and resettlement plan M&E monitoring and evaluation MFF multi-tranche financing facility NGO non-governmental organization NHA National Highway Authority PMU project management unit r.ft.