To Download the Complete Issue 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cornphíopa Le Chéile” (Hornpipe Together) to Keep Dancers Involved, Unified, As Well As Going Back to Their Traditional Irish Roots

CONRPHÍOPA LE CHÉILE A Chairde, I hope this email finds you safe & well. Our Marketing subcommittee of the International Workgroup in conjunction with the Music & Dance Committee of CLRG have been working hard and formed the idea to help engage with dancers of all levels throughout the World during this pandemic. We have created a CLRG Global Choreography Challenge named “Cornphíopa le Chéile” (Hornpipe Together) to keep dancers involved, unified, as well as going back to their Traditional Irish Roots. The purpose of this challenge is to promote our dance, our culture, our music and our heritage while allowing dancers all around the World to engage with their teachers and learn a new piece of dance that they might never have the chance to learn again. This is a combined challenge between our wonderful musicians, teachers & dancers from across the Globe. MUSIC; - To date our wonderful musicians have been contacted to invite them to compose 32 bars of a Hornpipe tune. This has to be a new piece of music created exclusively for this challenge and the chosen tunes will be uploaded to the CLRG website on the week of the 20th July, where it will be accessible to all dancers & teachers alike. CHOREOGRAPHY; - The dancers will create their own choreography in a traditional manner including e.g. rocks, cross keys, boxes, drums. They must not include toe walks, double clicks and most importantly it must be danced in a Traditional Style. There will be 3 different age categories Under 13, 13 – 16, 16-20 & Adult. The music speed will be 140. -

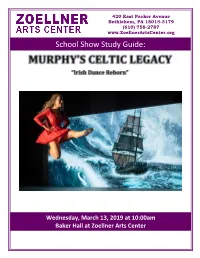

School Show Study Guide

420 East Packer Avenue Bethlehem, PA 18015-3179 (610) 758-2787 www.ZoellnerArtsCenter.org School Show Study Guide: Wednesday, March 13, 2019 at 10:00am Baker Hall at Zoellner Arts Center USING THIS STUDY GUIDE Dear Educator, On Wednesday, March 13, your class will attend a performance by Murphy’s Celtic Legacy, at Lehigh University’s Zoellner Arts Center in Baker Hall. You can use this study guide to engage your students and enrich their Zoellner Arts Center field trip. Materials in this guide include information about the performance, what you need to know about coming to a show at Zoellner Arts Center and interesting and engaging activities to use in your classroom prior to and following the performance. These activities are designed to go beyond the performance and connect the arts to other disciplines and skills including: Dance Culture Expression Social Sciences Teamwork Choreography Before attending the performance, we encourage you to: Review the Know before You Go items on page 3 and Terms to Know on pages 9. Learn About the Show on pages 4. Help your students understand Ireland on pages 11, the Irish dance on pages 17 and St. Patrick’s Day on pages 23. Engage your class the activity on pages 25. At the performance, we encourage you to: Encourage your students to stay focused on the performance. Encourage your students to make connections with what they already know about rhythm, music, and Irish culture. Ask students to observe how various show components, like costumes, lights, and sound impact their experience at the theatre. After the show, we encourage you to: Look through this study guide for activities, resources and integrated projects to use in your classroom. -

General Rules: 1

GENERAL RULES: 1. Competitors are restricted to amateurs whose teacher holds an A.D.C.R.G., T.C.R.G. or T.M.R.F. and are paid-up members of An Coimisiun, I.D.T.A.NA and I.D.T.A.M.A., and reside in the Mid- America region. All A.D.C.R.G’s, T.C.R.G’s and T.M.R.F.’s in the school must be paid – up members in all three organizations listed above. 2. The guideline for entry is that dancers have met one of the following qualifications between October 1, 2016 and September 30, 2017. a. Dancers Under 8, Under 9, and Under 10 may be entered at the teacher's discretion. b. Dancers Under 11, Under 12, and Under 13 must be 1st, 2nd or 3rd place medal winners in the Prizewinner Category at a feis in the Mid-America or Mid-Atlantic regions in each of the four dances (Reel, Slip Jig, Treble Jig, Hornpipe). Dancers in these age groups who compete in Preliminary Championship must place in the top 50% at a feis in the Mid-America or Mid-Atlantic Region. c. Dancers in the Under 11 age group will automatically qualify if they were recalled in the Under 10 category in the previous year. d. All dancers Under 14 and higher must be in Open Championship or must win in the top 50% of a Preliminary Championship competition in the Mid-America or Mid-Atlantic Region on at least one occasion. e. A dancer who qualified for the North American Championships at the previous Oireachtas is also qualified for this Oireachtas. -

Saturday June 12, 2021

FEIS REGISTRATION SUMMARY Feis start time is at 8:00 am Visit www.feisinginga.com for more information Syllabus approved on 16 April 2021 Up to May 21, all registration only accepted at www.quickfeis.com Feis caps are: (registration will close for those levels only once that cap has been reached) o Grades..................... 300 o PC/OC ..................... 250 All results will be printed and given out for FREE at the feis for both championship and grades FEIS INFORMATION levels All results will also be available for FREE on your Saturday June 12, 2021 QuickFeis account during and after the feis Competitions will be combined and split to The Westin Peachtree Plaza ensure that as many competitions will have 5 or Atlanta more dancers 210 Peachtree St NW, Atlanta, GA 30303 FEIS HIGHLIGHTS 3 round Preliminary and Open Championships. Awards given for hard and soft shoe rounds Minor, Junior, and Senior Champion Cup step down the line competition Meagan’s Reel – a competition for children with disabilities. Proceeds to benefit FOCUS (www.focus-ga.org) Tir na Nog (ages 2-4) and First Feis competitions BURKE CONNOLLY FEIS COMPETITION FEES FEIS RULES Entries not valid until full payment is received Competition Fees FEES Entries must be done on quickfeis.com. No mailed entries will be accepted. COMPETITIONS No refunds for any reason. Solo Grades Dancing NUMBER OF COMPETITORS: The Feis Committee Championship Cup $ 10 reserves the right to combine or split competitions. Meagan's Reel * RESULTS: Personal results will be FREE and will be Art and Music handed out shortly sometime after winners are ALL CHAMPIONSHIP announced. -

2014 ECRO Solo Results

<img src="cml.dll"> IDTANA Eastern Canadian Oireachtas Detailed Results #001 - Girls Under 8 Competitor 1-Treble-Jig 2-Reel 3-Set Dance Overall Competitor # Colin Ryan Danny Doherty Maria McCaul Rank Bernadette Fegan Julie Showalter Ian Boyd Points Competitor Name Ronan McCormack Eugene Harnett Sean Flynn School Name Event Result Event Result Event Result 112 1 (100.00) 8 (47.00) 4 (60.00) 1 Aselin Bates 1 (100.00) 1 (100.00) 2 (75.00) 782.00 Short School 1 (100.00) 1 (100.00) 1 (100.00) 1 (300.00) 1 (247.00) 1 (235.00) 115 7 (50.00) 1 (100.00) 1 (100.00) 2 Sammie Clegg 3 (65.00) 2 (75.00) 4 (60.00) 621.33 McGinley Academy 3 (65.00) 4 (56.33) 7 (50.00) 4 (180.00) 2 (231.33) 4 (210.00) 104 3 (65.00) 4 (60.00) 5 (56.00) 3 Zoe Baskinski 4 (60.00) 3 (65.00) 7 (50.00) 537.33 Goggin-Carroll 4 (60.00) 4 (56.33) 3 (65.00) 3 (185.00) 4 (181.33) 5 (171.00) 114 5 (56.00) 10 (41.00) 2 (75.00) 4 Sophie Mutch 7 (50.00) 6 (53.00) 3 (65.00) 501.00 Corrigan 10 (43.00) 10 (43.00) 2 (75.00) 6 (149.00) 8 (137.00) 3 (215.00) 122 8 (46.00) 13 (38.00) 9 (45.00) 5 Sarah Creaturo 2 (75.00) 7 (50.00) 5 (56.00) 488.00 Finnegan School 5 (56.00) 2 (75.00) 8 (47.00) 5 (177.00) 5 (163.00) 8 (148.00) 107 2 (75.00) 10 (41.00) 6 (53.00) 6 Evalyn Kelly-Taylor 10 (43.00) 15 (36.00) 6 (53.00) 468.00 Ni Fhearraigh O'Ceallaigh 2 (75.00) 14 (36.00) 5 (56.00) 2 (193.00) 15 (113.00) 6 (162.00) 113 21 (30.00) 6 (53.00) 3 (65.00) 7 Olivia Wilson 17 (33.50) 4 (60.00) 1 (100.00) 466.50 Butler - Fearon - O'Connor 20 (31.00) 11 (41.00) 6 (53.00) 20 (94.50) 6 (154.00) 2 (218.00) 102 -

TUNE BOOK Kingston Irish Slow Session

Kingston Irish Slow Session TUNE BOOK Sponsored by The Harp of Tara Branch of the Association of Irish Musicians, Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann (CCE) 2 CCE Harp of Tara Kingston Irish Slow Session Tunebook CCE KINGSTON, HARP OF TARA KINGSTON IRISH SLOW SESSION TUNE BOOK Permissions Permission was sought for the use of all tunes from Tune books. Special thanks for kind support and permission to use their tunes, to: Andre Kuntz (Fiddler’s Companion), Anthony (Sully) Sullivan, Bonnie Dawson, Brendan Taaffe. Brid Cranitch, Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann, Dave Mallinson (Mally’s Traditional Music), Fiddler Magazine, Geraldine Cotter, L. E. McCullough, Lesl Harker, Matt Cranitch, Randy Miller and Jack Perron, Patrick Ourceau, Peter Cooper, Marcel Picard and Aralt Mac Giolla Chainnigh, Ramblinghouse.org, Walton’s Music. Credits: Robert MacDiarmid (tunes & typing; responsible for mistakes) David Vrooman (layout & design, tune proofing; PDF expert and all-around trouble-shooter and fixer) This tune book has been a collaborative effort, with many contributors: Brent Schneider, Brian Flynn, Karen Kimmet (Harp Circle), Judi Longstreet, Mary Kennedy, and Paul McAllister (proofing tunes, modes and chords) Eithne Dunbar (Brockville Irish Society), Michael Murphy, proofing Irish Language names) Denise Bowes (cover artwork), Alan MacDiarmid (Cover Design) Chris Matheson, Danny Doyle, Meghan Balow, Paul Gillespie, Sheila Menard, Ted Chew, and all of the past and present musicians of the Kingston Irish Slow Session. Publishing History Tunebook Revision 1.0, October 2013. Despite much proofing, possible typos and errors in melody lines, modes etc. Chords are suggested only, and cannot be taken as good until tried and tested. Revision 0.1 Proofing Rough Draft, June, 2010 / Revision 0.2, February 2012 / Revision 0.3 Final Draft, December 2012 Please report errors of any type to [email protected]. -

IDTANA Southern Region 22Nd Annual Oireachtas

IDTANA Southern Region 22nd Annual Oireachtas November 30th, December 1st & 2nd, 2018 Marriot Marquis Houston 1777 Walker Street Houston, Texas, 77010 Chairpersons: Pat Hall, ADCRG Mary McGinty, ADCRG Adjudicators Christine Ayres (Australia) Aidan Comerford (England) Nora Corrigan (Canada) Kathy Dennehy (USA) Carmel Doyle (Australia) Jackie O’Leary Fanning (Canada) Sondra Greene (USA) Eileen Coyle Henry (USA) Bernard Hynes (Ireland) Stephen Masterson (England) Siobhan McDonnell-Monaghan (Ireland) Ronan McCormack (USA) Frances McGahan (England) Charles Moore (Ireland) Marie Moore (USA) Kerry Kelly Oster (USA) Edward Searle (USA) Pauline Shaw (England) Byron Tuttle (USA) Bernadette Short (Canada) Justine Ward- Mallinson (England) Musicians Ann Marie Acosta Williams, TCRG, New York, USA Brian Boyce, Pennsylvania, USA Anthony Davis, Birmingham, England William Furlong, New York, USA Brian Glynn, North Carolina, USA Brian Grant, ADCRG, Toronto, Canada Pat King, Toronto, Canada Chris McLoughlin, New Jersey, USA Niall Mulligan, New York, USA Sean O’Brien, Calgary, Canada Paul O’Donnell, Co Mayo, Ireland Cormac O’Shea, TCRG, Minnesota, USA Shannon Quinn, Nova Scotia, Canada Regan Wick, TCRG, New Jersey, USA 2 Entries Entries will be accepted from teachers who are members in good standing of An Coimisiún le Rincí Gaelacha, the IDTANA, and the IDTANA-Southern Region, for the 2018-2019 year. All Oireachtas entries must be submitted by teachers. All entries must be complete and contain all requested information. Incomplete entries will be returned. All members with dancers entered in the Oireachtas, who are in attendance for any part of the event, are required to work at least 4 (four) hours for the Oireachtas or pay a fine of $350.00. -

Important Information Regarding Oireachtas Rince Na Cruinne 2019 Koury Centre, Greensboro Sunday, 14Th April – 21St April 2019

Important Information Regarding Oireachtas Rince na Cruinne 2019 Koury Centre, Greensboro Sunday, 14th April – 21st April 2019 With the 2019 World Championships rapidly approaching, we would like to share the following information. Hotels within the Block Please note that the only hotels that are still accepting reservations that are on the block of CLRG are the Grandover Spa and Resort and the Holiday Inn – Coliseum. All other blocks in other partnership hotels are now closed. If you still have not booked and wish to avoid daily facility fees of $100 per person per day then: For the Grandover: Telephone (+1) 800-472-6301 ($169 per room per night) For the Holiday Inn - Coliseum : Telephone (+1) 336-294-4565 ($129 per room per night Please note that you must make reservations directly with the hotel using the above telephone numbers. If you are switched to Central Reservations of the Hotel Group, such reservations will be outside the block. Dancer Registration Packs Dancer registration packs will be available at the CLRG desk situated in the ground foyer between 12noon and 5:00pm on Saturday, 13th April 2019. On all other days, dancer registration packs can be collected from the CLRG desk between 7am and 5pm. The packs will include dancers’ wristband, certificates, patches and numbers. Welcome Desk/Program Sales CLRG members manning the welcome desk will assist in answering any questions regarding the Oireachtas. Teacher registrations will also operate from this Desk. The official programs will be available for sale at $25. Please note -

50Ú Oireachtas Rince Na Cruinne 2021 the 50Th World Irish Dancing

An Coimisiún le Rincí Gaelacha 50ú Oireachtas Rince na Cruinne 2021 The 50th World Irish Dancing Championships 2021 Dublin Convention Centre, Spencer Dock North Wall, Dublin D01 T1W6, Ireland Sunday, 28th March - Sunday 4th April, 2021 Contents Page 1 Venue and Dates Page 2 Contents and Information on Covid 19 Restrictions Page 3 50ú Oireachtas Rince na Cruinne 2021 Page 4 New for 2021 Page 5 Rules and Directives for Solo Dancing Page 6 World Solo Dancing Championships – Men/Boys Page 7 World Solo Dancing Championships – Ladies/Girls Page 8 Set Dances permitted Page 9 Age Concessions in Team Dancing Page 10 Rules & Directives for Céilí Dancing Page 12 World Céilí Dancing Championships Page 13 Rules & Directives for Figure Dancing Page 14 Figure Dancing - Musical Accompaniment & Ownership of Music Page 15 World Figure Dancing Championships Page 16 Rules and Directives for Dance Drama Page 17 World Dance Drama Championship Page 18 General Rules for Oireachtas Rince na Cruinne 2021 Page 23 Fees and closing dates Page 24 CLRG Media Policy and Information from the Marketing Committee Oireachtas Rince na Cruinne – Covid 19 Restrictions An Coimisiún le Rincí Gaelacha reserves the right to amend this syllabus to facilitate Covid19 restrictions. It is only by working together with a flexible, understanding and co-operative outlook, that this event can take place. At the time of the syllabus being released it is anticipated that there is a high possibility of some sort of social distancing requirement still being in place during the course of the Oireachtas. This could result in a maximum number of attendees being admitted into competition arenas at any one time and determine a finite number of people allowed to accompany any one competitor. -

Oireachtas Info

TEELIN SCHOOL OF IRISH DANCE EVERYTHING YOU NEED TO KNOW ABOUT AN OIREACHTAS (…WELL OK, ALMOST EVERYTHING…) WHAT IS AN OIREACHTAS? Within the context of Irish dance, Oireachtas (pronounced “O-ROCK-TUS”) is an annual regional championship competition. Prestigious in its own right, the Oireachtas also serves as a qualifying event for the National and World Competitions. The Teelin School of Irish Dance is part of the Southern Region, one of the seven regions in North America. The Southern Region Oireachtas is also referred to as “the SRO”. The Irish word "oireachtas" literally means "gathering". A convenient mnemonic for the spelling of Oireachtas is “Oh, I reach to a star”. (Note: Outside of Irish dancing context, the term “Oireachtas” is the national parliament or legislature of the Republic of Ireland.) WHAT ARE THE COMPETITIONS AT OIREACHTAS? There are two broad categories of competitions at Oireachtas: solos and teams. Solo championships at Oireachtas are qualifying events for the World Championships. Registration is open only to TCRG’s (certified teachers), who are ultimately responsible for registering the competitors they feel will positively reflect their school. Solo championships are divided by age and gender only, not by levels. Each competitor performs a hard shoe dance (treble jig or hornpipe) and a soft shoe dance (reel or slip jig) specified by the Oireachtas syllabus. The cumulative scores from those two rounds determine which dancers will be recalled to perform a hard shoe set dance in the third round. Dancers who advance to the third round are awarded placements, and the top percentage of dancers within eligible age groups qualify for the World Championships. -

Traditional Irish Musical Elements in the Solo-Piano Music of Ryan Molloy

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 2019 Traditional Irish Musical Elements in the Solo-Piano Music of Ryan Molloy Brian Thomas Murphy University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Celtic Studies Commons, Composition Commons, Music Performance Commons, and the Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons Recommended Citation Murphy, Brian Thomas, "Traditional Irish Musical Elements in the Solo-Piano Music of Ryan Molloy" (2019). Dissertations. 1668. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1668 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TRADITIONAL IRISH MUSICAL ELEMENTS IN THE SOLO-PIANO MUSIC OF RYAN MOLLOY by Brian Thomas Murphy A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School, the College of Arts and Sciences and the School of Music at The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved by: Dr. Elizabeth Moak, Committee Chair Dr. Edward Hafer Dr. Joseph Brumbeloe Dr. Ellen Elder Dr. Michael Bunchman ____________________ ____________________ ____________________ Dr. Elizabeth Moak Dr. Richard Kravchack Dr. Karen S. Coats Committee Chair Director, School of Dean of the Graduate School Music May 2019 COPYRIGHT BY Brian Thomas Murphy 2019 Published by the Graduate School ABSTRACT Music in Ireland has become increasingly popular in recent decades. There is no shortage of Irish musical groups, recordings, and live performances featuring Irish music both in Ireland and abroad. -

Éireann - a Taste of Ireland Cast and Creatives Bios

ÉIREANN - A TASTE OF IRELAND CAST AND CREATIVES BIOS CREATIVES BRENT PACE, MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA – Director/Creator/Principal Gaelforce Dance - Lead Principal Rhythms of Ireland - Lead Principal 6th Place World Championship 2011 3 x World Medal Holder 6 x Australian National Champion 12 x Regional Champion Featured Character on AB3’s Dancing Down Under Former President Irish Dance Commission Region TCRG Qualified Irish Dance Instructor Creator - A Taste of Ireland Principal - A Taste of Ireland 2012-present Creator - A Celtic Christmas Founder - Pace Entertainment Group Co-Founder - Pace Live Dance Company Brent Pace has been an Irish dancer for over 20 years. He is the son of one of Australia’s most prominent Irish dance teachers and has trained alongside the very best in London, Australia Dublin & the United States. His competitive dance career has taken him to achieve such feats as becoming a World Medallist, 6 Time National Champion and getting top placings at every major Irish dance competition in the World. Brent joined the show “The Rhythms of Ireland” in 2009 and by the beginning of 2011 he was the youngest Lead Dancer in the history of the company. He was then asked to perform the Principal role in the show’s first ever European tour. Since then, Brent has gone on to perform globally and joined Gaelforce Dance as the Principal Dancer in 2014, touring stadiums and theatres across the world. In 2017 Brent was honoured to be voted as one of the Presidents of the Irish dancing commission in the Queensland region, making him the youngest ever President in the history of Irish dancing.