The Fiddle Music of Connie O'connell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cornphíopa Le Chéile” (Hornpipe Together) to Keep Dancers Involved, Unified, As Well As Going Back to Their Traditional Irish Roots

CONRPHÍOPA LE CHÉILE A Chairde, I hope this email finds you safe & well. Our Marketing subcommittee of the International Workgroup in conjunction with the Music & Dance Committee of CLRG have been working hard and formed the idea to help engage with dancers of all levels throughout the World during this pandemic. We have created a CLRG Global Choreography Challenge named “Cornphíopa le Chéile” (Hornpipe Together) to keep dancers involved, unified, as well as going back to their Traditional Irish Roots. The purpose of this challenge is to promote our dance, our culture, our music and our heritage while allowing dancers all around the World to engage with their teachers and learn a new piece of dance that they might never have the chance to learn again. This is a combined challenge between our wonderful musicians, teachers & dancers from across the Globe. MUSIC; - To date our wonderful musicians have been contacted to invite them to compose 32 bars of a Hornpipe tune. This has to be a new piece of music created exclusively for this challenge and the chosen tunes will be uploaded to the CLRG website on the week of the 20th July, where it will be accessible to all dancers & teachers alike. CHOREOGRAPHY; - The dancers will create their own choreography in a traditional manner including e.g. rocks, cross keys, boxes, drums. They must not include toe walks, double clicks and most importantly it must be danced in a Traditional Style. There will be 3 different age categories Under 13, 13 – 16, 16-20 & Adult. The music speed will be 140. -

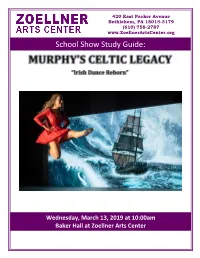

School Show Study Guide

420 East Packer Avenue Bethlehem, PA 18015-3179 (610) 758-2787 www.ZoellnerArtsCenter.org School Show Study Guide: Wednesday, March 13, 2019 at 10:00am Baker Hall at Zoellner Arts Center USING THIS STUDY GUIDE Dear Educator, On Wednesday, March 13, your class will attend a performance by Murphy’s Celtic Legacy, at Lehigh University’s Zoellner Arts Center in Baker Hall. You can use this study guide to engage your students and enrich their Zoellner Arts Center field trip. Materials in this guide include information about the performance, what you need to know about coming to a show at Zoellner Arts Center and interesting and engaging activities to use in your classroom prior to and following the performance. These activities are designed to go beyond the performance and connect the arts to other disciplines and skills including: Dance Culture Expression Social Sciences Teamwork Choreography Before attending the performance, we encourage you to: Review the Know before You Go items on page 3 and Terms to Know on pages 9. Learn About the Show on pages 4. Help your students understand Ireland on pages 11, the Irish dance on pages 17 and St. Patrick’s Day on pages 23. Engage your class the activity on pages 25. At the performance, we encourage you to: Encourage your students to stay focused on the performance. Encourage your students to make connections with what they already know about rhythm, music, and Irish culture. Ask students to observe how various show components, like costumes, lights, and sound impact their experience at the theatre. After the show, we encourage you to: Look through this study guide for activities, resources and integrated projects to use in your classroom. -

General Rules: 1

GENERAL RULES: 1. Competitors are restricted to amateurs whose teacher holds an A.D.C.R.G., T.C.R.G. or T.M.R.F. and are paid-up members of An Coimisiun, I.D.T.A.NA and I.D.T.A.M.A., and reside in the Mid- America region. All A.D.C.R.G’s, T.C.R.G’s and T.M.R.F.’s in the school must be paid – up members in all three organizations listed above. 2. The guideline for entry is that dancers have met one of the following qualifications between October 1, 2016 and September 30, 2017. a. Dancers Under 8, Under 9, and Under 10 may be entered at the teacher's discretion. b. Dancers Under 11, Under 12, and Under 13 must be 1st, 2nd or 3rd place medal winners in the Prizewinner Category at a feis in the Mid-America or Mid-Atlantic regions in each of the four dances (Reel, Slip Jig, Treble Jig, Hornpipe). Dancers in these age groups who compete in Preliminary Championship must place in the top 50% at a feis in the Mid-America or Mid-Atlantic Region. c. Dancers in the Under 11 age group will automatically qualify if they were recalled in the Under 10 category in the previous year. d. All dancers Under 14 and higher must be in Open Championship or must win in the top 50% of a Preliminary Championship competition in the Mid-America or Mid-Atlantic Region on at least one occasion. e. A dancer who qualified for the North American Championships at the previous Oireachtas is also qualified for this Oireachtas. -

61574447.Pdf

Title Towards a regional understanding of Irish traditional music Author(s) Kearney, David Publication date 2009-09 Original citation Kearney, D. 2009. Towards a regional understanding of Irish traditional music. PhD Thesis, University College Cork. Type of publication Doctoral thesis Link to publisher's http://library.ucc.ie/record=b1985733~S0 version Access to the full text of the published version may require a subscription. Rights © 2009, David Kearney http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/977 from Downloaded on 2017-02-12T14:09:41Z Towards a regional understanding of Irish traditional music David Kearney, B.A., H.Dip. Ed. Thesis presented for the award of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) National University of Ireland, Cork Supervisors: Professor Patrick O’Flanagan, Department of Geography Mel Mercier, Department of Music September 2009 Submitted to National University of Ireland, Cork 1 Abstract The geography of Irish traditional music is a complex, popular and largely unexplored element of the narrative of the tradition. Geographical concepts such as the region are recurrent in the discourse of Irish traditional music but regions and their processes are, for the most part, blurred or misunderstood. This thesis explores the geographical approach to the study of Irish traditional music focusing on the concept of the region and, in particular, the role of memory in the construction and diffusion of regional identities. This is a tripartite study considering people, place and music. Each of these elements impacts on our experience of the other. All societies have created music. Music is often associated with or derived from places. -

14/11/2019 11:44 the Kerry Archaeological & Historical Society

KAHS_Cover_2020.indd 1 14/11/2019 11:44 THE KERRY ARCHAEOLOGICAL & HISTORICAL SOCIETY EDITORIAL COMMENT CALL FOR PARTICIPATION: THE YOUNG It is scarcely possible to believe, that this magazine is the 30th in We always try to include articles the series. Back then the editor of our journal the late Fr Kieran pertaining to significant anniversaries, O’Shea, was having difficulties procuring articles. Therefore, the be they at county or national level. KERRY ARCHAEOLOGISTS’ CLUB Journal was not being published on a regular basis. A discussion This year, we commemorate the 50th Are you 15 years of age or older and interested in History, Archaeology, Museums and Heritage? In partnership with Kerry occurred at a council meeting as to how best we might keep in anniversary of the filming of Ryan’s County Museum, Kerry Archaeological & Historical Society is in the process of establishing a Young Kerry Archaeologists’ contact with our membership and the suggestion was made that a Daughter on the Dingle Peninsula. An Club, in which members’ children can participate. If you would like to get actively involved in programming and organizing “newsletter” might be a good idea. Hence, what has now become event, which catapulted the beauty of events for your peers, please send an email to our Education Officer: [email protected]. a highly regarded, stand-alone publication was born. Subsequent, the Peninsula onto the world stage, to this council meeting, the original sub-committee had its first resulting in the thriving tourism meeting. It was chaired by Gerry O’Leary and comprised of the industry, which now flourishes there. -

Saturday June 12, 2021

FEIS REGISTRATION SUMMARY Feis start time is at 8:00 am Visit www.feisinginga.com for more information Syllabus approved on 16 April 2021 Up to May 21, all registration only accepted at www.quickfeis.com Feis caps are: (registration will close for those levels only once that cap has been reached) o Grades..................... 300 o PC/OC ..................... 250 All results will be printed and given out for FREE at the feis for both championship and grades FEIS INFORMATION levels All results will also be available for FREE on your Saturday June 12, 2021 QuickFeis account during and after the feis Competitions will be combined and split to The Westin Peachtree Plaza ensure that as many competitions will have 5 or Atlanta more dancers 210 Peachtree St NW, Atlanta, GA 30303 FEIS HIGHLIGHTS 3 round Preliminary and Open Championships. Awards given for hard and soft shoe rounds Minor, Junior, and Senior Champion Cup step down the line competition Meagan’s Reel – a competition for children with disabilities. Proceeds to benefit FOCUS (www.focus-ga.org) Tir na Nog (ages 2-4) and First Feis competitions BURKE CONNOLLY FEIS COMPETITION FEES FEIS RULES Entries not valid until full payment is received Competition Fees FEES Entries must be done on quickfeis.com. No mailed entries will be accepted. COMPETITIONS No refunds for any reason. Solo Grades Dancing NUMBER OF COMPETITORS: The Feis Committee Championship Cup $ 10 reserves the right to combine or split competitions. Meagan's Reel * RESULTS: Personal results will be FREE and will be Art and Music handed out shortly sometime after winners are ALL CHAMPIONSHIP announced. -

2014 ECRO Solo Results

<img src="cml.dll"> IDTANA Eastern Canadian Oireachtas Detailed Results #001 - Girls Under 8 Competitor 1-Treble-Jig 2-Reel 3-Set Dance Overall Competitor # Colin Ryan Danny Doherty Maria McCaul Rank Bernadette Fegan Julie Showalter Ian Boyd Points Competitor Name Ronan McCormack Eugene Harnett Sean Flynn School Name Event Result Event Result Event Result 112 1 (100.00) 8 (47.00) 4 (60.00) 1 Aselin Bates 1 (100.00) 1 (100.00) 2 (75.00) 782.00 Short School 1 (100.00) 1 (100.00) 1 (100.00) 1 (300.00) 1 (247.00) 1 (235.00) 115 7 (50.00) 1 (100.00) 1 (100.00) 2 Sammie Clegg 3 (65.00) 2 (75.00) 4 (60.00) 621.33 McGinley Academy 3 (65.00) 4 (56.33) 7 (50.00) 4 (180.00) 2 (231.33) 4 (210.00) 104 3 (65.00) 4 (60.00) 5 (56.00) 3 Zoe Baskinski 4 (60.00) 3 (65.00) 7 (50.00) 537.33 Goggin-Carroll 4 (60.00) 4 (56.33) 3 (65.00) 3 (185.00) 4 (181.33) 5 (171.00) 114 5 (56.00) 10 (41.00) 2 (75.00) 4 Sophie Mutch 7 (50.00) 6 (53.00) 3 (65.00) 501.00 Corrigan 10 (43.00) 10 (43.00) 2 (75.00) 6 (149.00) 8 (137.00) 3 (215.00) 122 8 (46.00) 13 (38.00) 9 (45.00) 5 Sarah Creaturo 2 (75.00) 7 (50.00) 5 (56.00) 488.00 Finnegan School 5 (56.00) 2 (75.00) 8 (47.00) 5 (177.00) 5 (163.00) 8 (148.00) 107 2 (75.00) 10 (41.00) 6 (53.00) 6 Evalyn Kelly-Taylor 10 (43.00) 15 (36.00) 6 (53.00) 468.00 Ni Fhearraigh O'Ceallaigh 2 (75.00) 14 (36.00) 5 (56.00) 2 (193.00) 15 (113.00) 6 (162.00) 113 21 (30.00) 6 (53.00) 3 (65.00) 7 Olivia Wilson 17 (33.50) 4 (60.00) 1 (100.00) 466.50 Butler - Fearon - O'Connor 20 (31.00) 11 (41.00) 6 (53.00) 20 (94.50) 6 (154.00) 2 (218.00) 102 -

TUNE BOOK Kingston Irish Slow Session

Kingston Irish Slow Session TUNE BOOK Sponsored by The Harp of Tara Branch of the Association of Irish Musicians, Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann (CCE) 2 CCE Harp of Tara Kingston Irish Slow Session Tunebook CCE KINGSTON, HARP OF TARA KINGSTON IRISH SLOW SESSION TUNE BOOK Permissions Permission was sought for the use of all tunes from Tune books. Special thanks for kind support and permission to use their tunes, to: Andre Kuntz (Fiddler’s Companion), Anthony (Sully) Sullivan, Bonnie Dawson, Brendan Taaffe. Brid Cranitch, Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann, Dave Mallinson (Mally’s Traditional Music), Fiddler Magazine, Geraldine Cotter, L. E. McCullough, Lesl Harker, Matt Cranitch, Randy Miller and Jack Perron, Patrick Ourceau, Peter Cooper, Marcel Picard and Aralt Mac Giolla Chainnigh, Ramblinghouse.org, Walton’s Music. Credits: Robert MacDiarmid (tunes & typing; responsible for mistakes) David Vrooman (layout & design, tune proofing; PDF expert and all-around trouble-shooter and fixer) This tune book has been a collaborative effort, with many contributors: Brent Schneider, Brian Flynn, Karen Kimmet (Harp Circle), Judi Longstreet, Mary Kennedy, and Paul McAllister (proofing tunes, modes and chords) Eithne Dunbar (Brockville Irish Society), Michael Murphy, proofing Irish Language names) Denise Bowes (cover artwork), Alan MacDiarmid (Cover Design) Chris Matheson, Danny Doyle, Meghan Balow, Paul Gillespie, Sheila Menard, Ted Chew, and all of the past and present musicians of the Kingston Irish Slow Session. Publishing History Tunebook Revision 1.0, October 2013. Despite much proofing, possible typos and errors in melody lines, modes etc. Chords are suggested only, and cannot be taken as good until tried and tested. Revision 0.1 Proofing Rough Draft, June, 2010 / Revision 0.2, February 2012 / Revision 0.3 Final Draft, December 2012 Please report errors of any type to [email protected]. -

Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann (The Irish Musicians' Association) and the Politics of Musical Community in Irish Traditional Music

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2-2015 Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann (The Irish Musicians' Association) and the Politics of Musical Community in Irish Traditional Music Lauren Weintraub Stoebel Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/627 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] COMHALTAS CEOLTÓIRÍ ÉIREANN (THE IRISH MUSICIANS’ ASSOCIATION) AND THE POLITICS OF MUSICAL COMMUNITY IN IRISH TRADITIONAL MUSIC By LAUREN WEINTRAUB STOEBEL A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2015 ii © 2015 LAUREN WEINTRAUB STOEBEL All Rights Reserved iii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Peter Manuel______________________________ ________________ _________________________________________ Date Chair of Examining Committee Norman Carey_____________________________ ________________ _________________________________________ Date Executive Officer Jane Sugarman___________________________________________ Stephen Blum_____________________________________________ Sean Williams____________________________________________ Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iv Abstract COMHALTAS CEOLTÓIRÍ ÉIREANN (THE IRISH MUSICIANS’ ASSOCIATION) AND THE POLITICS OF MUSICAL COMMUNITY IN IRISH TRADITIONAL MUSIC By LAUREN WEINTRAUB STOEBEL Advisor: Jane Sugarman This dissertation examines Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann (The Irish Musicians’ Association) and its role in the politics of Irish traditional music communities. -

Charitable Tax Exemption

Charities granted tax exemption under s207 Taxes Consolidation Act (TCA) 1997 - 30 June 2021 Queries via Revenue's MyEnquiries facility to: Charities and Sports Exemption Unit or telephone 01 7383680 Chy No Charity Name Charity Address Taxation Officer Trinity College Dublin Financial Services Division 3 - 5 11 Trinity College Dublin College Green Dublin 2 21 National University Of Ireland 49 Merrion Sq Dublin 2 36 Association For Promoting Christian Knowledge Church Of Ireland House Church Avenue Rathmines Dublin 6 41 Saint Patrick's College Maynooth County Kildare 53 Saint Jarlath's College Trust Tuam Co Galway 54 Sunday School Society For Ireland Holy Trinity Church Church Ave Rathmines Dublin 6 61 Phibsboro Sunday And Daily Schools 23 Connaught St Phibsborough Dublin 7 62 Adelaide Blake Trust 66 Fitzwilliam Lane Dublin 2 63 Swords Old Borough School C/O Mr Richard Middleton Church Road Swords County Dublin 65 Waterford And Bishop Foy Endowed School Granore Grange Park Crescent Waterford 66 Governor Of Lifford Endowed Schools C/O Des West Secretary Carrickbrack House Convoy Co Donegal 68 Alexandra College Milltown Dublin 6 The Congregation Of The Holy Spirit Province Of 76 Ireland (The Province) Under The Protection Of The Temple Park Richmond Avenue South Dublin 6 Immaculate Heart Of Mary 79 Society Of Friends Paul Dooley Newtown School Waterford City 80 Mount Saint Josephs Abbey Mount Heaton Roscrea Co Tiobrad Aran 82 Crofton School Trust Ballycurry Ashford Co Wicklow 83 Kings Hospital Per The Bursar Ronald Wynne Kings Hospital Palmerstown -

Tribute to Seamus Creagh on World Fiddle Day, 20 May 2017, Scartaglin, County Kerry

Tribute to Seamus Creagh on World Fiddle Day, 20 May 2017, Scartaglin, County Kerry. "Jackie Daly and Seamus Creagh" Originally released in 1977 by Gael-Linn, CEF 057. Re-released in 2005 and now repackaged and released again, CEFCD057. Transcriptions and text by Paul de Grae for World Fiddle Day, Scartaglin, Co. Kerry, 20 May 2017. The featured recording for World Fiddle Day 2017 is "Jackie Daly & Seamus Creagh", issued by Gael-Linn in 1977. A marvellous recording by any standards, it was highly influential at the time, making many new converts to Sliabh Luachra music far beyond the semi-imaginary boundaries of the region. 1977 was a watershed year for Sliabh Luachra music. Though many of the important musical figures were still active, and set dancing was flourishing, the music had been largely ignored outside its own area. Precious recordings made in the late 1940s and 1950s for Raidió Éireann and the BBC remained inaccessible in the archives of those institutions. With the exception of Denis Murphy and Julia Clifford's outstanding album "The Star Above the Garter", released by Ceirníní Claddagh in 1968, and one or two tracks on hard-to-find compilation albums of Irish music, no recordings of authentic Sliabh Luachra music existed. Then suddenly in 1977 a flood of material, of the highest quality, became available. The English company, Topic Records, produced a set of six albums under the title "Music from Sliabh Luachra", starting with Seamus Ennis's 1952 BBC recordings of Pádraig O'Keeffe, Denis Murphy and Julia Clifford. The six albums in the series are: 1. -

Transactions of the Ossianic Society for the Years, 1853-1858

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA LOS ANGELES TRANSACTIONS OF THE OSSIANIC SOCIETY. TRANSACTIONS OP THE OSSIAMC SOCIETY, FOR THE YEAR 1856, VOL. IV. tstojrtye FjsiM n u )'5\)e9\c\)Z%, DUBLIN; PRINTED UNDER THE DIRECTION OF THE COUNCIL, FOR THE USE OF THE MEMBERS. 1859. JOHNSON REPRINT CORPORATION New York • London 1972 First reprinting 1972, Johnson Reprint Corporation Johnson Reprint Corporation Johnson Reprint Company Ltd. I ! 1 Fifth Avenue 24/28 Oval Road New York, N. Y. 10003 London, NW1 7DD, England F'rinted in the U.S.A. L2lOJi:i)e FJ21N H U )5\)&VC\)Z<U; OR, FENIAN POEMS EDITED BY JOHN O'DALY. DUBLIN : PRINTED FOR THE OSSIANIC SOCIETY, By JOHN O'DALY, 9, ANGLESEA-STREET. 1850. %\t (Dssianit Sorietn, Founded on St. Patrick's Day, 1853, for the Preservation and Publi- cation of MSS. in the Irish Language, illustrative of the Fenian period of Irish History, &c, with Literal Translations and Notes. OFFICERS ELECTED ON THE 17th MARCH, 1858. ^rrsifant : William S. O'Brien, Esq, M.R.I. A., Cahirmoyle, Newcastle West. 23icc-;j3rf5foriit5 : Rev. Ulick J. Bourke, Professor of Irish, St. Jarlattis College, Tuam. Rev. Euseby D. Cleaver, M.A., S. Barnabas, Pimlico, London. John O'Donovan, LL.D., M.R.I.A., Dublin. Standish Hayes O'Grady, Esq., Erinayh House, Castleconnell. Cnunril : Rev. John Clarke, C.C., Louth Professor Connellan, Queen's College, Cork. Rev. Sidney L. Cousins, Bantire, Cork. Rev. John Forrest, D.D., Kingstown. Rev. James Goodman, A.B., Ardgroom, Castletown, Berehaven. William Hackett, Esq., Midleton, Cork, Rev.