The World of Graft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seawood Village Movies

Seawood Village Movies No. Film Name 1155 DVD 9 1184 DVD 21 1015 DVD 300 348 DVD 1408 172 DVD 2012 704 DVD 10 Years 1175 DVD 10,000 BC 1119 DVD 101 Dalmations 1117 DVD 12 Dogs of Christmas: Great Puppy Rescue 352 DVD 12 Rounds 843 DVD 127 Hours 446 DVD 13 Going on 30 474 DVD 17 Again 523 DVD 2 Days In New York 208 DVD 2 Fast 2 Furious 433 DVD 21 Jump Street 1145 DVD 27 Dresses 1079 DVD 3:10 to Yuma 1124 DVD 30 Days of Night 204 DVD 40 Year Old Virgin 1101 DVD 42: The Jackie Robinson Story 449 DVD 50 First Dates 117 DVD 6 Souls 1205 DVD 88 Minutes 177 DVD A Beautiful Mind 643 DVD A Bug's Life 255 DVD A Charlie Brown Christmas 227 DVD A Christmas Carol 581 DVD A Christmas Story 506 DVD A Good Day to Die Hard 212 DVD A Knights Tale 848 DVD A League of Their Own 856 DVD A Little Bit of Heaven 1053 DVD A Mighty Heart 961 DVD A Thousand Words 1139 DVD A Turtle's Tale: Sammy's Adventure 376 DVD Abduction 540 DVD About Schmidt 1108 DVD Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter 1160 DVD Across the Universe 812 DVD Act of Valor 819 DVD Adams Family & Adams Family Values 724 DVD Admission 519 DVD Adventureland 83 DVD Adventures in Zambezia 745 DVD Aeon Flux 585 DVD Aladdin & the King of Thieves 582 DVD Aladdin (Disney Special edition) 496 DVD Alex & Emma 79 DVD Alex Cross 947 DVD Ali 1004 DVD Alice in Wonderland 525 DVD Alice in Wonderland - Animated 838 DVD Aliens in the Attic 1034 DVD All About Steve 1103 DVD Alpha & Omega 2: A Howl-iday 785 DVD Alpha and Omega 970 DVD Alpha Dog 522 DVD Alvin & the Chipmunks the Sqeakuel 322 DVD Alvin & the Chipmunks: Chipwrecked -

American Auteur Cinema: the Last – Or First – Great Picture Show 37 Thomas Elsaesser

For many lovers of film, American cinema of the late 1960s and early 1970s – dubbed the New Hollywood – has remained a Golden Age. AND KING HORWATH PICTURE SHOW ELSAESSER, AMERICAN GREAT THE LAST As the old studio system gave way to a new gen- FILMFILM FFILMILM eration of American auteurs, directors such as Monte Hellman, Peter Bogdanovich, Bob Rafel- CULTURE CULTURE son, Martin Scorsese, but also Robert Altman, IN TRANSITION IN TRANSITION James Toback, Terrence Malick and Barbara Loden helped create an independent cinema that gave America a different voice in the world and a dif- ferent vision to itself. The protests against the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights movement and feminism saw the emergence of an entirely dif- ferent political culture, reflected in movies that may not always have been successful with the mass public, but were soon recognized as audacious, creative and off-beat by the critics. Many of the films TheThe have subsequently become classics. The Last Great Picture Show brings together essays by scholars and writers who chart the changing evaluations of this American cinema of the 1970s, some- LaLastst Great Great times referred to as the decade of the lost generation, but now more and more also recognised as the first of several ‘New Hollywoods’, without which the cin- American ema of Francis Coppola, Steven Spiel- American berg, Robert Zemeckis, Tim Burton or Quentin Tarantino could not have come into being. PPictureicture NEWNEW HOLLYWOODHOLLYWOOD ISBN 90-5356-631-7 CINEMACINEMA ININ ShowShow EDITEDEDITED BY BY THETHE -

Season of the Witch Film Production Notes

SEASON OF THE WITCH Production Notes SEASON OF THE WITCH Synopsis Oscar® winner Nicolas Cage (National Treasure, Ghost Rider) and Ron Perlman (Hellboy, Hellboy II, Sons of Anarchy) star in this supernatural action adventure about a heroic Crusader and his closest friend who return home after decades of fierce fighting, only to find their world destroyed by the Plague. The church elders, convinced that a girl accused of being a witch is responsible for the devastation, command the two to transport the strange girl to a remote monastery where monks will perform an ancient ritual to rid the land of her curse. They embark on a harrowing, action-filled journey that will test their strength and courage as they discover the girl‟s dark secret and find themselves battling a terrifyingly powerful force that will determine the fate of the world. The years of brutal warfare in the name of God have stripped Behmen (Cage) of his taste for bloodshed—and his loyalty to the Church. Looking forward to a quiet retirement, Behmen and his comrade-in-arms Felson (Perlman) are bewildered to find their homeland deserted, unaware that Europe has been decimated by the Black Plague. While searching for food and supplies at the Palace at Marburg, the two knights are apprehended and called before the local Cardinal (Christopher Lee) to explain their unscheduled return from the East. The dying Cardinal threatens the pair with prison for desertion, unless they agree to a dangerous mission. The Cardinal‟s dungeon holds a young woman (Claire Foy) accused of being a witch who brings the Plague with her. -

Efficient Cryptography for the Next

Abstract of “Efficient Cryptography for the Next Generation Secure Cloud” by Alptekin K¨up¸c¨u, Ph.D., Brown University, May 2010. Peer-to-peer (P2P) systems, and client-server type storage and computation outsourc- ing constitute some of the major applications that the next generation cloud schemes will address. Since these applications are just emerging, it is the perfect time to design them with security and privacy in mind. Furthermore, considering the high- churn characteristics of such systems, the cryptographic protocols employed must be efficient and scalable. This thesis shows that cryptography can be used to efficiently and scalably provide security and privacy for the next generation cloud systems. We start by describing an efficient and scalable fair exchange protocol that can be used for exchanging files between participants of a P2P file sharing system. In this system, there are two central authorities that we introduce: the arbiter and the bank. We then try distributing these entities to reduce trust assumptions and to improve performance. Our work on distributing the arbiter leads to impossibility results, whereas our work on distributing the bank leads to a more general cloud computation result showing how a boss can employ untrusted contractors, and fine or reward them. We then consider cloud storage scenario, where the client outsources storage of her files to an untrusted server. We show how the client can challenge the server to prove that her file is kept intact, even when the files are dynamic. Next, we provide an agreement protocol for a dynamic message, where two parties agree on the latest version of a message that changes over time. -

Evil in the 'City of Angels'

Visit Our Showroom To Find The Perfect Lift Bed For You! April 24 - 30, 2020 2 x 2" ad 300 N Beaton St | Corsicana | 903-874-82852 x 2" ad M-F 9am-5:30pm | Sat 9am-4pm milesfurniturecompany.com FREE DELIVERY IN LOCAL AREA WA-00114341 W L M C A B L R G R C S P L N Your Key 2 x 3" ad P E Y S W Z A Z O V A T T O F L K D G U E N R S U H M I S J To Buying D O I B N P E M R Z Y U S A F and Selling! N K Z N U D E U W A R P A N E 2 x 3.5" ad Z P I M H A Z R O Q Z D E G Y M K E P I R A D N V G A S E B E D W T E Z P E I A B T G L A U P E M E P Y R M N T A M E V P L R V J R V E Z O N U A S E A O X R Z D F T R O L K R F R D Z D E T E C T I V E S I A X I U K N P F A P N K W P A P L Q E C S T K S M N T I A G O U V A H T P E K H E O S R Z M R “Penny Dreadful: City of Angels” on Showtime Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Lewis (Michener) (Nathan) Lane Supernatural Place your classified Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 Magda (Natalie) Dormer (1938) Los Angeles ad in the Waxahachie Daily Light, Merchandise High-End 2 x 3" ad Tiago (Vega) (Daniel) Zovatto (Police) Detectives Midlothian Mirror and Ellis Evil in the Peter (Craft) (Rory) Kinnear Murder County Trading1 Post! x 4" ad Deal Merchandise Word Search Maria (Vega) (Adriana) Barraza Espionage Call (972) 937-3310 Run a single item Run a single item priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 ‘City of Angels’ for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily Light, Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading2 x 3.5" Post ad and online at waxahachietx.com Natalie Dormer stars in “Penny Dreadful: City of Angels,” All specials are pre-paid. -

“Tom” Clausen a Legacy of Lead

Oral History Center University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California A. W. “Tom” Clausen A Legacy of Leadership: CEO of Bank of America and President of the World Bank Interviews conducted by Germaine LaBerge in 1996 Copyright © 2015 by The Regents of the University of California ii Since 1954 the Oral History Center of the Bancroft Library, formerly the Regional Oral History Office, has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral History is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well-informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is bound with photographs and illustrative materials and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ********************************* All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and A. W. “Tom” Clausen dated June 17, 1996. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

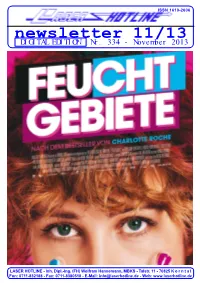

Newsletter 11/13 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 11/13 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 334 - November 2013 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 11 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 11/13 (Nr. 334) November 2013 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, Kolumne. liebe Filmfreunde! Unsere multimedialen Leser dürfen sich Ein Blick aus dem Fenster unserer Bü- übrigens freuen: es gibt Zuwachs auf roräume auf das in Nebel gehüllte unserem Youtube-Kanal. Zum Einen Korntal macht uns klar: es ist schon haben wir die Premiere des Films DIE wieder tiefster Herbst und der Winter NONNE in Stuttgart begleitet und uns klopft bereits an die Tür. Wer nicht mit Regisseur Guillaume Nicloux und gerade ein Kino gleich um die Ecke hat, Hauptdarstellerin Pauline Etienne un- der freut sich jetzt bestimmt umso mehr terhalten. Zum Anderen gibt es dort auf schöne Filmstunden in seinem ge- den Trailer zu REMEMBERING mütlichen Heimkino. Wie immer soll WIDESCREEN (in englischer Sprache) jedoch niemand bei unserem Newsletter zu sehen, einem Dokumentarfilm über zu kurz kommen. So gibt es nicht nur das “Widescreen Weekend” in den neuesten Filmblog von Wolfram Bradford. Der Film selbst befindet sich Hannemann, in dem aktuelle Kinofilme momentan in der Post-Produktions- gelobt und zerrissen werden, sondern Phase und soll im kommenden Jahr im auch wieder jede Menge Informationen Kino seine Premiere feiern. Wir halten zu anstehenden DVD- und Blu-ray- Sie natürlich auf dem Laufenden. Und Veröffentlichungen für Heimkinofans. -

How to Order: 1.Pilih Judul Yang Di Inginkan Dengan Mengetik "1" Dikolom Yg Disediakan & JANGAN Merubah Format Susunan List Ini 2.Isi Form Pemesanan (WAJIB!) 3

EMAIL : [email protected] YM: henz_magician TELP :XL 081910293132 (CALL OR SMS) How To Order: 1.Pilih judul yang di inginkan dengan mengetik "1" dikolom yg disediakan & JANGAN Merubah Format susunan list ini 2.Isi Form Pemesanan (WAJIB!) 3. Save pesanan anda dan ganti nama file list ini dengan nama id anda (Order / id kaskus atau chip / nama anda sendiri ) 4.Kirimkan File List ini ke email : [email protected] 5.Konfirmasikan pesanan anda ke 081910293132 (SMS) & Sebutkan type dan ukuran hardisk yg diinginkan (Jika Ingin Membeli Hardisk baru) How To Order: 1.Pilih judul yang di inginkan dengan mengetik "1" dikolom yg disediakan & JANGAN Merubah Format susunan list ini 3. Save pesanan anda dan ganti nama file list ini dengan nama id anda (Order / id kaskus atau chip / nama anda sendiri ) 4.Kirimkan File List ini ke email : [email protected] 5.Konfirmasikan pesanan anda ke 081910293132 (SMS) & Sebutkan type dan ukuran hardisk yg diinginkan (Jika Ingin Membeli Hardisk baru) How To Order: JANGAN Merubah Format susunan list ini 3. Save pesanan anda dan ganti nama file list ini dengan nama id anda (Order / id kaskus atau chip / nama anda sendiri ) 5.Konfirmasikan pesanan anda ke 081910293132 (SMS) & Sebutkan type dan ukuran hardisk yg diinginkan (Jika Ingin Membeli Hardisk baru) JENIS Total Terpilih HD Movie #NAME? HD Music Concert #NAME? 3D Movie #NAME? Documenter #NAME? PC Games #NAME? Asian TV Series & Movie #NAME? TV Series 710.36 Comedy & Indo Movie 2.2 Anime 0 Tokusatsu 0 Smack Down 0 TOTAL #NAME? Harap form pengiriman diisi dengan jelas dan benar Rek. -

A Sony Pictures Classics Release

World Premiere: 2010 Toronto International Film Festival 2010 Hamptons International Film Festival 2010 Chicago International Film Festival 2010 Truly Moving Picture Award winner A Sony Pictures Classics Release Release Date: 11/19/2010 (NY &LA) | TRT: 113 min | MPAA: Rated R East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor Falco Ink Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Erin Bruce Judy Chang Carmelo Pirrone Annie McDonough Melody Korenbrot Lindsay Macik 850 7th Ave, Ste 1005 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 550 Madison Ave, 8th Floor NY, NY 10019 Los Angeles, CA 90036 New York, NY 10022 212-445-7100 tel 323-634-7001 tel 212-833-8833 tel 212-445-0623 fax 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8844 fax MADE IN DAGENHAM | FACT SHEET THE FIGHT FOR EQUAL PAY Please Note: the Paycheck Fairness Act is scheduled to be voted on by the Senate on or around November 17th. This Act has been passed by the President and the House of Representatives. More information on this Act is below The Good News • Women are the primary breadwinners in nearly 2/3 of American families • Women represent 47% of all American workers • 51.4% of all managers are women (that's up from 26% in 1980) • Between 1997-2007, the number of women-owned businesses grew by 44% (twice as fast as men-owned firms) • Women-owned businesses have created 500,000 jobs • The majority of college graduates are women The Bad News • In this current recession, while American women have held on to more jobs than American men -- with families scraping by on the one paycheck women bring home -- because women are paid less, entire families are struggling to stretch the paycheck • During this recession, women's individual earnings have actually fallen, making it even harder for families to make ends meet on their one paycheck. -

DVD LIST 7-1-2018 Xlsx

Seawood Village Movie List 1155 9 1184 21 1015 300 348 1408 172 2012 1119 101 Dalmatians 1117 12 Dogs of Christmas: Great Puppy Rescue 352 12 Rounds 862 12 Years a Slave 843 127 Hours 446 13 Going on 30 259 13 Hours 474 17 Again 208 2 Fast 2 Furious 433 21 Jump Street 737 22 JumpStreet 1145 27 Dresses 1079 3:10 to Yuma 1101 42: The Jackie Robinson Story 449 50 First Dates 1205 88 Minutes 177 A Beautiful Mind 444 A Brilliant Young Mind 643 A Bug's Life 255 A Charlie Brown Christmas 227 A Christmas Carol 581 A Christmas Story 1223 A Dog's Purpose 506 A Good Day to Die Hard 1120 A Hologram For The King 212 A Knights Tale 848 A League of Their Own 1222 A Mermaid's Tale 498 A Merry Friggin Christmas 1323 A Quiet Place 1273 A Star is Born 1108 Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter Page 1 of 33 Seawood Village Movie List 1322 Acromony 812 Act of Valor 819 Adams Family & Adams Family Values 1332 Adrift 83 Adventures in Zambezia 745 Aeon Flux 12 After Earth 585 Aladdin & the King of Thieves 582 Aladdin (Disney Special edition) 79 Alex Cross 198 Alexander and the terrible, Horrible, No Good 947 Ali 1004 Alice in Wonderland 525 Alice in Wonderland - Animated 1248 Alien Covenant 838 Aliens in the Attic 1262 All I Want For Christmas is You 1299 All The Money In The World 780 Allegiant 827 Aloha 1367 Alpha 1103 Alpha & Omega 2: A Howl-iday 522 Alvin & the Chipmunks the Sqeakuel 322 Alvin & the Chipmunks: Chipwrecked 854 Alvin and the Chipmonks Driving Dave Crazy 371 Alvin and The Chipmonks: The Road Chip 1272 American Assasin 1028 American Heist 1282 American -

AP Courses Go by the Board a Delightful Event

Page 13 Page 17 Avril Lavigne in OpEd: concert To walk or not to walk eat A Delightful Event Northside’s Spring Musical by Zahra Lalani times stay- B This year’s cast of the Spring ing as late at Musical comprises of unprecedent- 10 p.m.” edly few seniors. Despite this, the The seniors involved in the production cast felt that of “Little Women,” Rana Marks (Jo after each March), Adv. 810, Steven Solomon show they (Orchestra, Piano), Adv. 810, Joel grew stron- Rodriguez (Laurie), Adv. 808, John ger, and by Mussman (Mr. Lawrence), Adv. Sunday’s 806, and Jennifer Ceisel (Marmee show, ev- March), Adv. 800, unanimously eryone was The agree that “Little Women” is one of ready to step the best musical performances that outside their oof Northside has put together. comfort “Little Women” tells the story zones and of the four March girls, Meg (Annie try some- Vol. 9 No. 8 Northside College Preparatory High School April 2008 9 No. 8 Northside College Preparatory High School Vol. Mitran, Adv. 909), Jo (Marks), Beth thing new (Bethany Roeschley, Adv. 906), and with their Amy (Mary Mussman, Adv. 109) charac- and how they remain courageous ters. John in the face of adversity, despite the Mussman H many trials and tribulations that did a little come their way. The story takes dance while place in 19th century Concord, Roeschley Massachusetts. Their father is away played at war and prospects of a festive the piano. Christmas are dim due to financial Marks near- The four March girls, played by Bethany Roeschely, Adv. -

My Blueberry Nights April…

MAGAMAGA MY BLUEBERRY NIGHTS APRIL… “possibly Britain’s most beautiful cinema...” (BBC) APRIL 2008 Issue 37 www.therexcinema.com 01442 877759 Mon-Sat 10.30-6pm Sun 4.30-6.30pm To advertise email [email protected] WELCOME Gallery 5 April Evenings 9-18 Coming Soon 19 April Films at a glance 19 April Matinees 20-27 Dear Mrs Trellis 29, 31 SEAT PRICES: Circle £7.00 Concessions £5.50 At Table £9.00 Concessions £7.50 Royal Box (seats 6) £11.00 or for the Box £60.00 BOX OFFICE: 01442 877759 Mon to Sat 10.30 – 6.00 Sun 4.30 – 6.30 (Credit/Debit card booking fee 50p) Disabled and flat access: through the gate Brad Pitt - Las Vegas, 1994. Photo credit: Photographs (c) 2007 by Annie on High Street (right of apartments) Leibovitz from the documentary Annie Leibovitz: Life Through a Lens, Barbara Some of the girls and boys you see at the Box Leibovitz, Director. Mon 28th 7.30. Don't miss. Office and Bar: Rosie Abbott Bethany McKay END OF CREDITS FOR CANCELLATIONS… Henry Beardshaw Linda Moss n 1st April the 48 hr rule ends. Instead there will be no more credit Julia Childs Louise Ormiston Lindsey Davies Izzi Robinson vouchers at all or refunds on any cancellations. For over two years Holly Gilbert Georgia Rose Othe box office has been advising me of difficulties arising from Becky Ginn Diya Sagar this. The girls and boys are well tuned to casual abuses of our generous Tom Glasser Miranda Samson Beth Hannaway Tina Thorpe system.