Are Three Legs Appropriate? Or Even Sufficient? by Henry Fogel

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mediation Is Provided by Our Management Staff

What We Do. By arrangement with Jack Price, Price Rubin & Partners has been a leader in the Artist Management, Concert Management, Music, Entertainment and Performing Arts Industries since 1984 providing direct marketing ser- vices to emerging and highly-credentialed classical, jazz, dance, cross-over, country, western, folk, new-age and film artists. Our roster includes some of the most-accomplished and awarded artists performing today. More than just traditional artist representation services, Premium Management delivers super-targeted direct marketing to concert presenters and performing arts organizations who engage performing artists. Our marketing staff makes approximately 3500-4000 calls each month to decision-makers who buy talent. Our clients receive highly-individ- ualized targeted marketing that focuses on branding and getting them much-needed considering from performing arts presenters who will be engaging artists in the future. When interest is expressed our managers take over the lead and work to establish a relationship between the presenter and artist. Contract mediation is provided by our management staff. We also offer various marketing services as well as patron marketing, public relations, adver- tising, fundraising, audience development, general artist management, PRPRadioOne and Price Rubin Music Television. Founder Jack Price. The indomitable Jack Price started Price Rubin & Partners in 1984 in response to his own career as an internationally renowned and celebrated concert pianist. Jack took on the role as manager -

Chapter Three the Philadelphia Orchestra Stokowski Inherited 15

<The "(PhiCacCeCpfiia Sound": The Formative Years (1912-1920) Candis nUreC^eCcf The "Philadelphia Sound": The Formative Years (1912-1920) HONORS THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements For the UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS HONORS PROGRAM By Candis Threlkeld Denton, Texas April 1999 CamJm (J- <rSuJLJa) Student APfljROVED: acuity Advisor a-/ C Cjjy, Honors Director The "Philadelphia Sound": The Formative Years (1912-1920) HONORS THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements For the UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS HONORS PROGRAM By Candis Threlkeld Denton, Texas April 1999 Student APPROVED: Faculty Advisor • n juts • Honors Director Acknowledgements This paper would not have been possible without the help of the following people, who aided me immensely while I was researching in Philadelphia: JoAnne Barry - archivist with the Philadelphia Orchestra Marjorie Hassen - curator of the Stokowski Collection, Otto E. Albrecht Music Library, University of Pennsylvania John Pollock and the Student Staff of the Ross Reading Room - Van Pelt Library, University of Pennsylvania Paul Sadedov - Music Librarian at the Free Library of Philadelphia Members of the Philadelphia Orchestra - who were a daily inspiration to me (I would particularly like to thank those members who took the time out to talk with me: Luis Biava, Booker Rowe, Richard Woodhams, David Bilger, Elizabeth Starr, and Pete Smith.) Phil - the security guard at the Academy who always helped me find JoAnne Barry, and who always greeted "Texas" with such a wonderful smile in the mornings Stephanie Wilson - one of my dearest friends who let me stay at her house during the second week of my trip - and who gave me great reed advice before my senior recital Janet Miller, Laura Lucas, and Darryl - Stephanie's housemates, who always made me always feel welcome I would also like to thank the following people at the University of North Texas for all of their assistance: Maestro Anshel Brusilow - director of orchestras and my faculty advisor Dr. -

Philharmonic Au Dito R 1 U M

LUBOSHUTZ and NEMENOFF April 4, 1948 DRAPER and ADLER April 10, 1948 ARTUR RUBINSTEIN April 27, 1948 MENUHIN April 29, 1948 NELSON EDDY May 1, 1948 PHILHARMONIC AU DITO R 1 U M VOL. XLIV TENTH ISSUE Nos. 68 to 72 RUDOLF f No S® Beethoven: S°"^„passionala") Minor, Op. S’ ’e( MM.71l -SSsr0*“” « >"c Beethoven. h6tique") B1DÛ SAYÂO o»a>a°;'h"!™ »no. Celeb'“’ed °P” CoW»b» _ ------------------------- RUOOtf bKch . St«» --------------THE pWUde'Pw»®rc’^®®?ra Iren* W°s’ „„a olh.r,„. sr.oi «■ o'--d s,°3"' RUDOLF SERKIN >. among the scores of great artists who choose to record exclusively for COLUMBIA RECORDS Page One 1948 MEET THE ARTISTS 1949 /leJ'Uj.m&n, DeLuxe Selective Course Your Choice of 12 out of 18 $10 - $17 - $22 - $27 plus Tax (Subject to Change) HOROWITZ DEC. 7 HEIFETZ JAN. 11 SPECIAL EVENT SPECIAL EVENT 1. ORICINAL DON COSSACK CHORUS & DANCERS, Jaroff, Director Tues. Nov. 1 6 2. ICOR CORIN, A Baritone with a thrilling voice and dynamic personality . Tues. Nov. 23 3. To be Announced Later 4. PATRICE MUNSEL......................................................................................................... Tues. Jan. IS Will again enchant us-by her beautiful voice and great personal charm. 5. MIKLOS GAFNI, Sensational Hungarian Tenor...................................................... Tues. Jan. 25 6. To be Announced Later 7. ROBERT CASADESUS, Master Pianist . Always a “Must”...............................Tues. Feb. 8 8. BLANCHE THEBOM, Voice . Beauty . Personality....................................Tues. Feb. 15 9. MARIAN ANDERSON, America’s Greatest Contralto................................. Sun. Mat. Feb. 27 10. RUDOLF FIRKUSNY..................................................................................................Tues. March 1 Whose most sensational success on Feb. 29 last, seated him firmly, according to verdict of audience and critics alike, among the few Master Pianists now living. -

Carnegie Hall

CARNEGIE HALL 136-2-1E-43 ALFRED SCOTT, Publisher. 156 Fifth Avenue. New York &njoy these supreme moments oj music again ancl again in pour own home, on VICTORS RECORDS Hear these brilliant interpretations of ARTUR RUBINSTEIN TSCHAIKOWSKY -CONCERTO NO. 1, IN B FLAT MINOR, Op. 23. With the London Symphony Orchestra, John Barbirolli, conductor. Album DM-180 $4.50* GRIEG—CONCERTO IN A MINOR, Op. 16. With the Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy, conductor. Album DM-900 $3.50* BRAHMS — INTERMEZZI AND RHAPSODIES. Album M-893 $4.50* SCHUBERT — TRIO NO. 1, IN B FLAT MAJOR, Op. 99. With Jascha Heifetz, violinist and Emanuel Feuermann, ’cellist. Album DM-923 $4.50* CHOPIN—CONCERTO NO. 1, IN E MINOR, Op. 11 With the London Symphony Orchestra, John Barbirolli, conductor. Album DM-418 $4.50* CHOPIN — MAZURKAS (complete in 3 volumes) Album M-626, Vol. 1 $5.50* Album M-656, Vol. 2 $5.50" Album M-691, Vol. 3 $4.50* •Suggested list prices exclusive of excise tax. Listen to the Victor Red Seal Records programs on Station WEAR at 11:15 P.M., Monday through Friday and Station WQXR at 10 to 10:30 P.M., Monday, Wednesday and Friday. Keep Going With Music • Buy War Bonds Every Pay Day The world's greatest artists are on Victor Records Carnegie Hall Program BUY WAR BONDS AND STAMPS 9 it heard If you have a piano which you would care to donate for the duration of the War kindly communicate with Carnegie Hall Recreation Unit for men of the United Nations, Studio 603 Carnegie Hall. -

Toscanini VII, 1937-1942

Toscanini VII, 1937-1942: NBC, London, Netherlands, Lucerne, Buenos Aires, Philadelphia We now return to our regularly scheduled program, and with it will come my first detailed analyses of Toscanini’s style in various music because, for once, we have a number of complete performances by alternate orchestras to compare. This is paramount because it shows quite clear- ly that, although he had a uniform approach to music and insisted on both technical perfection and emotional commitment from his orchestras, he did not, as Stokowski or Furtwängler did, impose a specific sound on his orchestras. Although he insisted on uniform bowing in the case of the Philadelphia Orchestra, for instance, one can still discern the classic Philadelphia Orchestra sound, despite its being “neatened up” to meet his standards. In the case of the BBC Symphony, for instance, the sound he elicited from them was not far removed from the sound that Adrian Boult got out of them, in part because Boult himself preferred a lean, clean sound as did Tosca- nini. We shall also see that, for better or worse, the various guest conductors of the NBC Sym- phony Orchestra did not get vastly improved sound result out of them, not even that wizard of orchestral sound, Leopold Stokowki, because the sound profile of the orchestra was neither warm in timbre nor fluid in phrasing. Toscanini’s agreement to come back to New York to head an orchestra created (pretty much) for him is still shrouded in mystery. All we know for certain is that Samuel Chotzinoff, representing David Sarnoff and RCA, went to see him in Italy and made him the offer, and that he first turned it down. -

The Phiiharmonic-Symphony Society 1842 of New York Consolidated 1928

THE PHIIHARMONIC-SYMPHONY SOCIETY 1842 OF NEW YORK CONSOLIDATED 1928 1952 ONE HUNDRED ELEVENTH SEASON 1953 Musical Director: DIMITRI MITROPOULOS Guest Conductors: BRUNO WALTER, GEORGE SZELL, GUIDO CANTELLI Associate Conductor: FRANCO AUTORI For Young People’s Concerts: IGOR BUKETOFF CARNEGIE HALL 5176th Concert SUNDAY AFTERNOON, APRIL 19, 1953, at 2:30 Under the Direction of DIMITRI MITROPOULOS Assisting Artist: ARTUR RUBINSTEIN, Pianist FRANCK-PIERNE Prelude, Chorale and Fugue SCRIABIN The Poem of Ecstasy, Opus 54 Intermission SAINT-SAËNS Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, No. 2, G minor, Opus 22 I. Andante sostenuto II. Allegretto scherzando III. Presto Artur Rubinstein FRANCK Symphonic Variations for Piano and Orchestra Artur Rubinstein (Mr. Rubinstein plays the Steinway Piano) ARTHUR JUDSON, BRUNO ZIRATO, Managers THE STEINWAY is the Official Piano of The Philharmonic-Symphony Society COLUMBIA AND VICTOR RECORDS THE PHILHARMONIC-SYMPHONY SOCIETY OF NEW YORK BOARD OF DIRECTORS •Floyd G. Blair........ ........President •Mrs. Lytle Hull... Vice-President •Mrs. John T. Pratt Vice-President ♦Ralph F. Colin Vice-President •Paul G. Pennoyer Vice-President ♦David M. Keiser Treasurer •William Rosenwald Assistant Treasurer •Parker McCollester Secretary •Arthur Judson Executive Secretary Arthur A. Ballantine Arthur A. Houghton, Jr. Mrs. William C. Breed Mrs. Arthur Lehman Chester Burden Mrs. Henry R. Luce •Mrs. Elbridge Gerry Chadwick David H. McAlpin Henry E. Coe Richard E. Myers Pierpont V. Davis William S. Paley Maitland A. Edey •Francis T. P. Plimpton Nevil Ford Mrs. David Rockefeller Mr. J. Peter Grace, Jr. Mrs. George H. Shaw G. Lauder Greenway Spyros P. Skouras •Mrs. Charles S. Guggenheimer •Mrs. Frederick T. Steinway •William R. -

The Harlingen Auditorium and Harlingen Concert Association 51 Years Young – and the Beat Goes on Norman Rozeff, November 2006 (Revised 12/07, 2/11)

The Harlingen Auditorium and Harlingen Concert Association 51 Years Young – And the Beat Goes On Norman Rozeff, November 2006 (revised 12/07, 2/11) Civic leaders and the city fathers recognized early on that a sizeable auditorium capable of hosting name attractions would be an important asset to the city. In April 1926 even before such an auditorium was a reality Mayor Ewing had approached the Southwest Chautauqua Organization about bringing its major performers to the city. It had toured such stalwarts as the violinist Efrem Zimbalist, Polish pianist Ignacy Jan Paderewski, and lecturer Herbert Hoover. It is in 1927 that the Harlingen Municipal Auditorium, 1114 Fair Park Blvd., is approved for construction at a cost of $125,000. Its site is where the annual Valley Mid-Winter ag- ricultural fairs are held, and it is expected to be utilized as part of the fair activities. It is completed before mid-1928 and seats 1,800. The Hurricane of 1933 causes extensive to the auditorium, so it is extensively renovated. Reopened in late 1935, a new cornerstone dated 1936 is placed in it. The entrance offers a art deco façade. The interior is also of art deco design and has a state of the art stage. Reconfigured, it then seats over 2,200. The city government people who approved the expenditures were: Mayor Sam Botts; com- missioners J.J.Burk, George Waters, Neil Madeley, Dr. E.A. Davis, and H.C. Ware. The architect was Stanley Bliss with the Ramsey Brothers doing the contracting. Since the year 1928 when Harlingen was first blessed with one of the finest civic audito- riums in the Lower Rio Grande Valley, the community has always enticed topnotch en- tertainment. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Is Exceptional Beauty, Depth and Richness of Tone

More smokers every day are turning to Chesterfield 's happy combination of mild ripe Amer ican and aromatic Turkish to CHESTERF/ELOS baccos-the world's best ciga the H appy Combination rette tobaccos. for More Smoking Pleasure When you try them you wi/1 know why Chesterfields give millions of men and women more smoking pleasure •.. why THEY SATISFY ... the blend that can 't be copied ... the RIGHT COMBINATION of the world's best cigarette tobaccos Copyrighc 1939, LI GGEIT & MYERS ToBACCO Co. Copyright 1929 by ALFRED SCOTT, Publisher, 156 Fift h Ave., New York, N. Y. r CARNEGIE HALL PROGRAM 3 • •UA ,EA'Y.:E :t;;,y;;E"" R-A D 1:0,. ~ "I could sit through it ~ Y ours For Keeps ~ again!" ~ ~ How often have you remarked that after a li( ,,,.,~ Carnegie Hall concert. You can salisfy your ),; LI( heart's desire with a Lafayette Automatic ~ On Victor Records H Phono-Radio Combination You can hear the ~ f-4 beautiful symphonies that thrilled you to- .;. .,, night, in your own home .. faithfully, mag- .,.. ~ nificently reproduced on a Lafayette. Send · >! for our booklet, or cal! W Alker 5-8883. ;:1:1 c( )lo The Boston ~ LAFAYETTE RADIOS ~ -I JOO SIXTH AVE. • NEW YORK O Symphony Orchestra 11111 o 1 o v M , :!I .r ::r·xv ::1 v :1 liJ ORATORIO SOCIETY OF N. Y. Serge Koussevitzky, Conductor Carnegie Hall Announcements Sixty-Fifth Season JANUARY ALBERT STOESSEL, Conductor • One of the special characteristics of the Boston Symphony Orchestra is exceptional beauty, depth and richness of tone. Saturday Eve. Jan. -

The Concerts at Lewisohn Stadium, 1922-1964

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 2009 Music for the (American) People: The Concerts at Lewisohn Stadium, 1922-1964 Jonathan Stern The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2239 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] MUSIC FOR THE (AMERICAN) PEOPLE: THE CONCERTS AT LEWISOHN STADIUM, 1922-1964 by JONATHAN STERN VOLUME I A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2009 ©2009 JONATHAN STERN All Rights Reserved ii This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Music in satisfaction of the Dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Professor Ora Frishberg Saloman Date Chair of Examining Committee Professor David Olan Date Executive Officer Professor Stephen Blum Professor John Graziano Professor Bruce Saylor Supervisory Committee THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii Abstract MUSIC FOR THE (AMERICAN) PEOPLE: THE LEWISOHN STADIUM CONCERTS, 1922-1964 by Jonathan Stern Adviser: Professor John Graziano Not long after construction began for an athletic field at City College of New York, school officials conceived the idea of that same field serving as an outdoor concert hall during the summer months. The result, Lewisohn Stadium, named after its principal benefactor, Adolph Lewisohn, and modeled much along the lines of an ancient Roman coliseum, became that and much more. -

The Animated Movie Guide

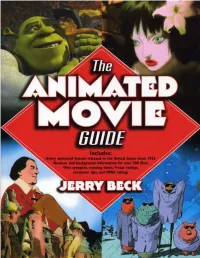

THE ANIMATED MOVIE GUIDE Jerry Beck Contributing Writers Martin Goodman Andrew Leal W. R. Miller Fred Patten An A Cappella Book Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Beck, Jerry. The animated movie guide / Jerry Beck.— 1st ed. p. cm. “An A Cappella book.” Includes index. ISBN 1-55652-591-5 1. Animated films—Catalogs. I. Title. NC1765.B367 2005 016.79143’75—dc22 2005008629 Front cover design: Leslie Cabarga Interior design: Rattray Design All images courtesy of Cartoon Research Inc. Front cover images (clockwise from top left): Photograph from the motion picture Shrek ™ & © 2001 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Photograph from the motion picture Ghost in the Shell 2 ™ & © 2004 DreamWorks L.L.C. and PDI, reprinted with permission by DreamWorks Animation; Mutant Aliens © Bill Plympton; Gulliver’s Travels. Back cover images (left to right): Johnny the Giant Killer, Gulliver’s Travels, The Snow Queen © 2005 by Jerry Beck All rights reserved First edition Published by A Cappella Books An Imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated 814 North Franklin Street Chicago, Illinois 60610 ISBN 1-55652-591-5 Printed in the United States of America 5 4 3 2 1 For Marea Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction ix About the Author and Contributors’ Biographies xiii Chronological List of Animated Features xv Alphabetical Entries 1 Appendix 1: Limited Release Animated Features 325 Appendix 2: Top 60 Animated Features Never Theatrically Released in the United States 327 Appendix 3: Top 20 Live-Action Films Featuring Great Animation 333 Index 335 Acknowledgments his book would not be as complete, as accurate, or as fun without the help of my ded- icated friends and enthusiastic colleagues. -

Edward Kilenyi, Jr. Materials

Edward Kilenyi, Jr. Materials Kilenyi I Kilenyi Jr. to father ● 49 letters and 1 letter fragment from Kilenyi Jr. to father ● 5 postcards to father ● 19 telegrams to father (1940s) or to mother (North African tour) ● 8 envelopes, 4 with their respective letters and 4 loose 1. Letter to Edward Kilenyi Sr. from Edward Kilenyi Jr., June 1, [1933]. [Budapest]. People mentioned: Ernő Dohnányi, Irén Senn, Elza Galafrés Dohnányi, Alfred Cortot, Pásztor, Arthur Judson, Halli Huberman. 2. Letter to Edward Kilenyi Sr. from Edward Kilenyi Jr., with envelope, July 3, 1933. Paris, Hotel Malherbe. People mentioned: Alfred Cortot, Ernő Dohnányi, Robert Casadeus, Eugene Ormandy. 3. Letter to Edward Kilenyi Sr. from Edward Kilenyi Jr., with envelope, October 1, 1933. Paris. People mentioned: Ethel Kilenyi, Josef Slenczynski, Ruth Slenczynska, [Gerald?] Langelaan and son [George Langelaan]. 4. Letter to Edward Kilenyi Sr. from Edward Kilenyi Jr., with envelope, October 22, 1933. Paris. People mentioned: Rudolf Serkin, Adolf Busch, Joseph Hoffmann. 5. Letter to Edward Kilenyi Sr. from Edward Kilenyi Jr., with envelope, October 10, 1934. Paris, Claridge’s Hotel. People mentioned: Wilhelm Fürtwangler, Joseph Goebbels, Dr. Schiff, Marcel de Valmalète. 6. Letter to Edward Kilenyi Sr. from Edward Kilenyi Jr., January 6, 1935. Milan, Grand Hotel Continental. People mentioned: Ethel Kilenyi, Giacomo Balla, Sir Geoffrey Fry, Elza Galafrés Dohnányi, cousin Laczi. 7. Letter to Edward Kilenyi Sr. from Edward Kilenyi Jr., January 4, 1941. [New York]. People mentioned: Ethel Kilenyi, Fulkerson, Jack Salter, Yehudi Menuhin. 8. Letter to Edward Kilenyi Sr. from Edward Kilenyi Jr., November 15, 1941. [New York]. People mentioned: Jascha Heifitz, Olin Downes, Rudolf Serkin, Claudio Arrau, Moe [Moses Smith], Eugene Stinson, Alexander Greiner, Theodore Steinway, William Steinway, Jack Salter, Giannino Agostinaccho, Frances McLanahan, Ilya, Arthur Judson. -

The History of CBS New York Television Studios: 1937-1965

1 The History of CBS New York Television Studios: 1937-1965 By Bobby Ellerbee and Eyes of a Generation.com Preface and Acknowledgements This is the first known chronological listing that details the CBS television studios in New York City. Included in this exclusive presentation by and for Eyes of a Generation, are the outside performance theaters and their conversion dates to CBS Television theaters. This compilation gives us the clearest and most concise guide yet to the production and technical operations of television’s early days and the efforts at CBS to pioneer the new medium. This story is told to the best of our abilities, as a great deal of the information on these facilities is now gone…like so many of the men and women who worked there. I’ve told this as concisely as possible, but some elements are dependent on the memories of those who were there many years ago, and from conclusions drawn from research. If you can add to this with facts or photos, please contact me, as this is an ongoing project. (First Revision: August 6, 2018). Eyes of a Generation would like to offer a huge thanks to the many past and present CBS people that helped, but most especially to television historian and author David Schwartz (GSN), and Gady Reinhold (CBS 1966 to present), for their first-hand knowledge, photos and help. Among the distinguished CBS veterans providing background information are Dr. Joe Flaherty, George Sunga, Dave Dorsett, Allan Brown, Locke Wallace, Rick Scheckman, Jim Hergenrather, Craig Wilson and Bruce Martin.