A Functional Analysis of Gerundive Constructions in English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Does English Have a Genitive Case? [email protected]

2. Amy Rose Deal – University of Massachusetts, Amherst Does English have a genitive case? [email protected] In written English, possessive pronouns appear without ’s in the same environments where non-pronominal DPs require ’s. (1) a. your/*you’s/*your’s book b. Moore’s/*Moore book What explains this complementarity? Various analyses suggest themselves. A. Possessive pronouns are contractions of a pronoun and ’s. (Hudson 2003: 603) B. Possessive pronouns are inflected genitives (Huddleston and Pullum 2002); a morphological deletion rule removes clitic ’s after a genitive pronoun. Analysis A consists of a single rule of a familiar type: Morphological Merger (Halle and Marantz 1993), familiar from forms like wanna and won’t. (His and its contract especially nicely.) No special lexical/vocabulary items need be postulated. Analysis B, on the other hand, requires a set of vocabulary items to spell out genitive case, as well as a rule to delete the ’s clitic following such forms, assuming ’s is a DP-level head distinct from the inflecting noun. These two accounts make divergent predictions for dialects with complex pronominals such as you all or you guys (and us/them all, depending on the speaker). Since Merger operates under adjacency, Analysis A predicts that intervention by all or guys should bleed the formation of your: only you all’s and you guys’ are predicted. There do seem to be dialects with this property, as witnessed by the American Heritage Dictionary (4th edition, entry for you-all). Call these English 1. Here, we may claim that pronouns inflect for only two cases, and Merger operations account for the rest. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Genitive Constructions in Coptic Barbara Egedi

Genitive constructions in Coptic Barbara Egedi 1. Introduction 1.1. Definition of ‘Coptic’ Coptic is the language of Christian Egypt (4th to 14th century) written in a specific version of the Greek alphabet. It was gradually superseded by Ara- bic from the ninth century onward, but it survived to the present time as the liturgical language of the Christian church of Egypt. In this paper I examine only one of its main dialects, the Sahidic Coptic and I use a transcription which simply reflects the Coptic letters irrespectively of phonological de- tails.1 1.2. UG in the reconstruction of dead languages Natural languages are claimed to have universal properties or principles which constitute what is referred to as Universal Grammar. Accepting cer- tain universal principles and observing the corresponding parameters in Coptic, we can also analyse a language without living native speakers, and explain its structural relations with the help of coherent models. For example, it is considered a universal principle that the projections of lexical heads are extended by one or more functional projections. If we assume that it can be demonstrated in many languages, why could not we suppose the same in the case of Coptic? Indeed, as it will be shown in chap- ter 4, there are at least two functional projections above Coptic lexical noun phrase as well. The aim of this paper is to provide an adequate account of the basic structure of the Coptic NP within the theoretical framework of the Mini- malist Program (a short summary of which will be found in the following section); at the same time, I intend to find the answer to unsolved questions related to genitive constructions. -

Introduction to Gothic

Introduction to Gothic By David Salo Organized to PDF by CommanderK Table of Contents 3..........................................................................................................INTRODUCTION 4...........................................................................................................I. Masculine 4...........................................................................................................II. Feminine 4..............................................................................................................III. Neuter 7........................................................................................................GOTHIC SOUNDS: 7............................................................................................................Consonants 8..................................................................................................................Vowels 9....................................................................................................................LESSON 1 9.................................................................................................Verbs: Strong verbs 9..........................................................................................................Present Stem 12.................................................................................................................Nouns 14...................................................................................................................LESSON 2 14...........................................................................................Strong -

A Study of Three Variants of Gerund Construction from the Contrastive Perspective of Social and Natural Academic Abstracts on Construction Grammar Theory1

2020 年 6 月 中国应用语言学(英文) Jun. 2020 第 43 卷 第 2 期 Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics Vol. 43 No. 2 A Study of Three Variants of Gerund Construction from the Contrastive Perspective of Social and Natural Academic Abstracts on Construction Grammar Theory1 Yan J IN & Mingtuo YANG Northwest Normal University Abstract English gerund construction is a system composed of 3 variants, including “Gerund + ø”, “Gerund + of + NP”, and “Gerund + NP”. The noun and verb attributes of the 3 variants are recursive, and in theory their frequencies vary regularly in different styles. An abstract is placed before the beginning of an academic papers, which has the basic characteristics of conciseness and generalization, and has special requirements for the use of gerunds. The purpose of this study was to empirically explore the system of gerund construction in abstracts of natural science and social science papers, and to specifically explore the inherent characteristics of noun and verb properties of the 3 variants. For this purpose, two corpora were constructed, one is about abstracts of natural science papers, and the other is about abstracts of social science papers. Finally, the results of chi-square test showed that there was no significant difference in the frequencies of the 3 variants in the abstracts of natural science and social science papers, and the two corpora can be studied as a whole. In the combined corpus, there were significant differences in the frequencies of the 3 gerund variants. The frequencies of these 3 variants and their gerund properties showed a recursive change. Keywords: gerund construction, gerund variants, Construction Grammar, nominalization, gerund system 1 The study was supported by the Humanities and Social Sciences Research Planning Fund of Ministry of Education for Western and Frontier Areas (14XJA740001). -

Basic Linguistic Theory, 2

Basic Linguistic Theory 2 Basic Linguistic Theory R. M. W. Dixon The three volumes of Basic Linguistic Theory provide a new and fundamental characterization of the nature of human languages and a comprehensive guide to their description and analysis. The first volume addresses the methodology for recording, analysing, and comparing languages. Volume 3 (which will be published in 2011) examine and explain every underlying principle of gram- matical organization and consider how and why grammars vary. Volume 1 Methodology Volume 2 Grammatical Topics Volume 3 Further Grammatical Topics (in preparation) AcompletelistofR.M.W.Dixon’sbooksmaybefoundonpp.488–9 Basic Linguistic Theory Volume 2 Grammatical Topics R. M. W. DIXON The Cairns Institute James Cook University 1 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dp Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries Published in the United States by Oxford University Press Inc., New York ©R.M.W.Dixon2010 Themoralrightsoftheauthorhavebeenasserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. -

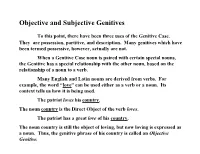

Objective and Subjective Genitives

Objective and Subjective Genitives To this point, there have been three uses of the Genitive Case. They are possession, partitive, and description. Many genitives which have been termed possessive, however, actually are not. When a Genitive Case noun is paired with certain special nouns, the Genitive has a special relationship with the other noun, based on the relationship of a noun to a verb. Many English and Latin nouns are derived from verbs. For example, the word “love” can be used either as a verb or a noun. Its context tells us how it is being used. The patriot loves his country. The noun country is the Direct Object of the verb loves. The patriot has a great love of his country. The noun country is still the object of loving, but now loving is expressed as a noun. Thus, the genitive phrase of his country is called an Objective Genitive. You have actually seen a number of Objective Genitives. Another common example is Rex causam itineris docuit. The king explained the cause of the journey (the thing that caused the journey). Because “cause” can be either a noun or a verb, when it is used as a noun its Direct Object must be expressed in the Genitive Case. A number of Latin adjectives also govern Objective Genitives. For example, Vir miser cupidus pecuniae est. A miser is desirous of money. Some special nouns and adjectives in Latin take Objective Genitives which are more difficult to see and to translate. The adjective peritus, -a, - um, meaning “skilled” or “experienced,” is one of these: Nautae sunt periti navium. -

Genitive Case

GENITIVE CASE The Genitive is the third and last case existing in both English and Latin. In English, all pronouns have a genitive case that shows possession: "his", "her", "my", "their", "whose", etc. These answer the question "Belonging to whom or what?" Regular nouns in English also have a genitive form: in the singular, the ending "'s" is added; in the plural, s'. Consider the following examples: Their father is here. The man's father is here. The boys' father is here. In Latin, the Genitive case may also show possession. However, it may be used for some other things as well, as you will see later on. It's ending of course varies depending on the original ending of the noun: for a-nouns, the singular is -ae and the plural is -ārum; for both us- and um-nouns, the singular is -ī and the plural is - ōrum. Consider the following chart: Nominative, Accusative, and Genitive Cases a-nouns us-nouns um-nouns sg. pl. sg. pl. sg. pl. Nominative a ae us ī um a Accusative Genitive ae ārum ī ōrum ī ōrum A genitive is normally paired with another noun in the sentence which it modifies. In English, it is always placed immediately before the noun it modifies: for example, "my soup", "the boy's shirt", etc. But in Latin, a genitive may be placed either before or after the noun it modifies: for example, feminae panes, panes feminae. In fact, a genitive may occasionally even be separated by another word: panes sunt feminae. Also, keep in mind that the grammatical possession that the genitive case signifies is a fairly broad and vague connection. -

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR of OLD ENGLISH Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies

AN INTRODUCTORY GRAMMAR OF OLD ENGLISH MEDievaL AND Renaissance Texts anD STUDies VOLUME 463 MRTS TEXTS FOR TEACHING VOLUme 8 An Introductory Grammar of Old English with an Anthology of Readings by R. D. Fulk Tempe, Arizona 2014 © Copyright 2020 R. D. Fulk This book was originally published in 2014 by the Arizona Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies at Arizona State University, Tempe Arizona. When the book went out of print, the press kindly allowed the copyright to revert to the author, so that this corrected reprint could be made freely available as an Open Access book. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE viii ABBREVIATIONS ix WORKS CITED xi I. GRAMMAR INTRODUCTION (§§1–8) 3 CHAP. I (§§9–24) Phonology and Orthography 8 CHAP. II (§§25–31) Grammatical Gender • Case Functions • Masculine a-Stems • Anglo-Frisian Brightening and Restoration of a 16 CHAP. III (§§32–8) Neuter a-Stems • Uses of Demonstratives • Dual-Case Prepositions • Strong and Weak Verbs • First and Second Person Pronouns 21 CHAP. IV (§§39–45) ō-Stems • Third Person and Reflexive Pronouns • Verbal Rection • Subjunctive Mood 26 CHAP. V (§§46–53) Weak Nouns • Tense and Aspect • Forms of bēon 31 CHAP. VI (§§54–8) Strong and Weak Adjectives • Infinitives 35 CHAP. VII (§§59–66) Numerals • Demonstrative þēs • Breaking • Final Fricatives • Degemination • Impersonal Verbs 40 CHAP. VIII (§§67–72) West Germanic Consonant Gemination and Loss of j • wa-, wō-, ja-, and jō-Stem Nouns • Dipthongization by Initial Palatal Consonants 44 CHAP. IX (§§73–8) Proto-Germanic e before i and j • Front Mutation • hwā • Verb-Second Syntax 48 CHAP. -

Adnominal Possession: Combining Typological and Second Language Perspectives

Adnominal possession: combining typological and second language perspectives Björn Hammarberg and Maria Koptjevskaja-Tamm 1. Introduction The notion of possession and its linguistic manifestations have been a popular topic in linguistic literature for a long time. What we will attempt here is to explore the domain of adnominal possession - pos- sessive relations and their manifestations within the noun phrase - in one particular language from two combined points of view: the ty- pological characteristics of the system, and the picture that emerges from second language learners' attempts to handle adnominal pos- session in production. We are focusing on Swedish, a language with a distinctive and rather elaborate system of adnominal possession. Our aim is twofold: to present an overview of how the Swedish sys- tem of adnominal possessive constructions works, and to show how acquisitional aspects connect with typological aspects in this domain. The English phrases Peter's hat, my son and a boy's leg all exem- plify prototypical cases of adnominal possession whereby one entity, the possessee, referred to by the head of the possessive noun phrase, is represented as possessed in one way or another by another entity, the possessor, referred to by the attribute. It has become a common- place in linguistics that possession is a difficult, if not impossible, notion to grasp (for a survey of adnominal possession in a cross- linguistic perspective cf. Koptjevskaja-Tamm 2001). However, even though it seems impossible to give a reasonable general definition for all the meanings covered by possessive constructions across lan- guages and even in one language, we can still provide criteria for identifying a possessive construction, or possessive constructions in a language. -

Particle Verbs in Italian

Particle Verbs in Italian Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades des Doktors der Philosophie an der Universit¨at Konstanz Fachbereich Sprachwissenschaft vorgelegt von Quaglia, Stefano Tag der m ¨undlichen Pr ¨ufung: 23 Juni 2015 Referent: Professor Christoph Schwarze Referentin: Professorin Miriam Butt Referent: Professor Nigel Vincent Konstanzer Online-Publikations-System (KOPS) URL: http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:bsz:352-0-376213 3 Zusammenfassung Die vorliegende Dissertation befasst sich mit italienischen Partikelverben (PV), d.h. Kon- struktionen die aus einem Verb und einer (meist r¨aumlicher) Partikel, wie andare fuori ‘hinaus-gehen’ oder buttare via ‘weg-schmeißen’. Solche komplexe Ausdr¨ucke sind in manchen Hinsichten interessant, erstmal sprachvergleichend, denn sie instantiieren eine morpho-syntaktische Struktur, die in germanischen Sprachen (wie Deutsch, Englisch, Schwedisch und Holl¨andisch) pervasiv ist, aber in den romanischen Sprachen nicht der- maßen ausgebaut ist. Da germanische Partikelverben Eingenschaften aufweisen, die zum Teil f¨ur die Morphologie, zum teil f¨ur die Syntax typisch sind, ist ihr Status in formalen Grammatiktheorien bestritten: werden PV im Lexikon oder in der Syntax gebaut? Dieselbe Frage stellt sich nat¨urlich auch in Bezug auf die italienischen Partikelverben, und anhand der Ergebnisse meiner Forschung komme ich zum Schluss, dass sie syntaktisch, und nicht morphologisch, zusammengestellt werden. Die Forschungsfragen aber die in Bezug auf das grammatische Verhalten italienischer Partikelverben von besonderem Interesse sind, betreffen auch Probleme der italienischen Syntax. In meiner Arbeit habe ich folgende Forschungsfragen betrachtet: (i) Kategorie und Klassifikation Italienischer Partikeln, (ii) deren Interaktion mit Verben auf argument- struktureller Ebene, (iii) strukturelle Koh¨asion zwischen Verb und Partikel und deren Repr¨asentation. -

Dative and Genitive Variability in Late Modern English: Exploring Cross-Constructional Variation and Change

Dative and genitive variability in Late Modern English: Exploring cross-constructional variation and change Christoph Wolk (Freiburg Institute for Advanced Studies) Joan Bresnan (Stanford University) Anette Rosenbach (Tanagra Wines) Benedikt Szmrecsanyi (Freiburg Institute for Advanced Studies) We present a cross-constructional approach to the history of the genitive alternation and the dative alternation in Late Modern English (AD 1650 to AD 1999), drawing on richly annotated datasets and modern statistical modeling techniques. We identify cross- constructional similarities in the development of the genitive and the dative alternation over time (mainly with regard to the loosening of the animacy constraint), a development which parallels distributional changes in animacy categories in the corpus material. Theoretically, we transfer the notion of ‘probabilistic grammar’ to historical data and claim that the corpus models presented reflect past speaker’s knowledge about the distribution of genitive and dative variants. The historical data also helps to determine what is constant (and timeless) in the effect of selected factors such as animacy or length, and what is variant. Acknowledgments We wish to express our thanks to the Freiburg Institute for Advanced Studies (FRIAS) for funding the project “Predicting syntax in space and time”. We are also grateful to the audiences of the March 2010 workshop on “Probabilistic syntax: phonetics, diachrony, and synchrony” (hosted by the FRIAS) and the November 2010 workshop on “The development of syntactic alternations” (Stanford University) for constructive feedback. We acknowledge helpful comments and suggestions by Ludovic De Cuypere, Beth Levin and Joanna Nykiel, and owe gratitude to Stephanie Shih for advice on coding final sibilancy, and to Katharina Ehret, whose assistance has contributed significantly to the development of our research.